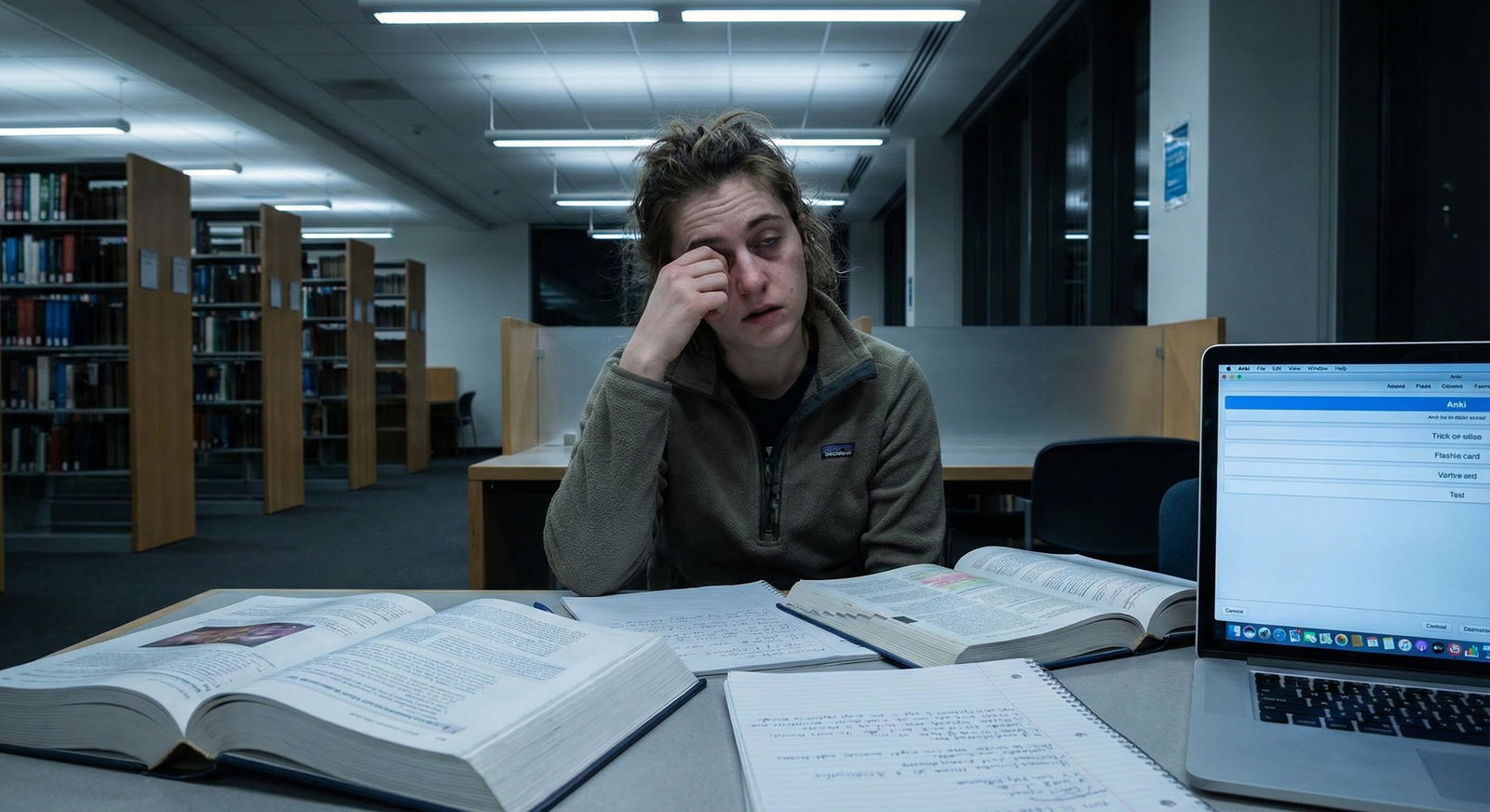

The typical advice about “just power through” on clinical rotations is garbage. Decision fatigue is chewing up medical students long before burnout gets formally labeled.

You are not tired because you “cannot handle the hours.” You are tired because you are making 300+ small, semi‑consequential decisions a day with zero structure. Your cognitive bandwidth is bleeding out through a thousand cuts: “Should I preround one more time?” “Do I present this lab?” “Do I ask the resident now or later?” “Do I stay for this case or go study?”

Let me walk you through a framework to stop that bleed.

1. What Decision Fatigue Actually Looks Like On Rotations

Forget abstract psychology for a minute. On the wards, decision fatigue shows up in very specific, predictable ways.

By post‑call afternoon or day 6 of a hard week, I have seen students:

- Stare at the EMR for 10 minutes, “reviewing labs,” and retain nothing.

- Document the same note twice because they cannot remember if they already did it.

- Ask the attending a question they already wrote down the answer to that morning.

- Agree to every “hey can you just…” request from nurses, social work, residents—then miss conference entirely.

You know this pattern:

Morning:

- You decide what time to wake up.

- Which patients to preround on first.

- Whether to look at vitals, meds, or labs first.

- How much to write in your pre‑note.

- Which details to include in your presentation.

- Whether to speak up when the intern gets something slightly wrong.

By noon conference, your brain has done several hours of “micro‑triage” on social interactions, information filtering, and self‑presentation. Before you even crack open UWorld.

That is decision fatigue. Not dramatic. Just relentless.

Clinical decision fatigue vs. ordinary tired

You are not just sleepy. You see it in:

- Shorter patience with patients and nurses.

- Impulsive charting errors (“normal” exam on a clearly abnormal patient).

- Avoidance of reading (“I’ll just scroll my phone for five minutes” that becomes 40).

- Defaulting to “whatever you think is best” when asked for your assessment.

If, by mid‑afternoon, it feels physically harder to choose between two tasks (“Should I finish this note or call the consultant?”), your decision machinery is already overloaded.

The solution is not motivation. It is structure.

2. A Simple Model: Four Buckets of Decisions You Must Control

Let me break your clinical day into four distinct decision domains. If you do not separate them, everything feels like one giant blur of “stuff I should be doing better.”

Here are the buckets:

- Time decisions

- Cognitive decisions (what to think about)

- Social decisions (how to interact, when to speak)

- Self‑regulation decisions (sleep, food, exercise, “life stuff”)

Decision fatigue happens when you leave all four entirely ad‑hoc. You want to pre‑decide 60–70% of them with rules, templates, and defaults.

Think of it as moving from “decide in the moment” to “execute a pre‑made choice.”

| Domain | Main Cost | Primary Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Time decisions | Overcommitment | Fixed schedule |

| Cognitive focus | Fragmentation | Checklists |

| Social decisions | Anxiety, approval | Scripts & rules |

| Self-regulation | Energy crashes | Non-negotiable habits |

We will go through each domain with concrete frameworks you can actually use tomorrow.

3. Time Decisions: Constrain the Day Before It Starts

Most students run their rotation days on vibes. They show up, react to the team, squeeze in studying “when there is time,” and then beat themselves up at night.

That chaos is expensive.

The “Two‑Anchor” day structure

On busy rotations, you can reliably control only two blocks of time:

- Pre‑round block (from arrival until rounds start)

- Evening block (from getting home until sleep)

Everything else is fluid. Accept that.

So you anchor those two blocks with pre‑made decisions.

Pre‑round anchor:

- Exact arrival time (e.g., 5:20 AM, not “around 5–5:30”).

- Patient review order.

- A fixed pattern for each patient.

Example pattern:

- Check overnight vitals / events.

- New labs / imaging.

- MAR for meds/changes.

- Very short focused exam.

- Jot 2–3 bullet updates for presentation.

You run this same pattern on every patient. No “Should I check X? Should I go see them first?” You execute.

Evening anchor:

Decide the night before:

- End‑of‑day cutoff (e.g., “Laptop closed by 10:15 PM no matter what.”)

- A default study plan pattern for that rotation:

- 5 questions (or 10) + quick review

- 20–30 minutes of targeted reading (topic from the day)

- 5 minutes planning tomorrow

You are not letting 8 PM “future you” decide whether to study. Past you already decided what “minimum viable evening block” looks like.

The 3–2–1 daily constraints

On heavy inpatient services, this structure keeps time decisions minimal:

- 3 patients you will know cold (your primaries)

- 2 “learning topics” you will read about that night

- 1 small professional behavior to improve that day

Write them down in the morning.

Example:

- Patients: 412, 458, 462

- Topics: DKA management, heparin bridging

- Behavior: Avoid apologizing for asking questions

Everything else is bonus. This reduces the endless “Should I do more?” self‑flagellation that drains you.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Time | 40 |

| Cognitive | 120 |

| Social | 80 |

| Self-Regulation | 30 |

You will still make dozens of time decisions during the day, but your big ones are already locked.

4. Cognitive Decisions: What Deserves Your Brain Today?

On rotations, the EMR and the ward will happily fragment your brain into useless confetti.

You do not have the bandwidth to “pay attention to everything.” You need narrow beams, not floodlights.

The “Clinical Attention Funnel”

For each patient, you want three layers of attention. And you want to move through them in order, not randomly.

Signal layer (must know)

- Overnight events, vitals, key labs, major complaints.

- Simple question: “Could this change management or indicate deterioration?”

Context layer (helpful to know)

- Past medical history, hospital course, consultant notes.

- Question: “Does this change how I interpret the signal?”

Noise layer (ignore unless needed today)

- Old consults, ancient imaging, minor lab drifts.

When you open the chart, you decide once: “I am staying in signal layer until rounds start.” You do not go hunting through old notes out of anxiety.

Use short, rigid checklists

Students who rely on “I will remember everything” are the ones who get crushed by decision fatigue. They keep mentally re‑scanning:

“Did I check I/O? Did I look at today’s labs? Did I see new imaging?”

Use a 6–8 item checklist per patient. Reuse it daily.

Example general medicine preround checklist:

- Vitals trend (24 hours)

- Overnight events / nursing notes

- Labs: CBC, BMP, specific relevant labs

- Med changes / new orders

- Exam: focused on active issues

- Today’s “question” about this patient (what you want to understand better)

You run the checklist. Then you stop. You do not ask, “Should I check more?” The default is no, unless there is a clear reason.

Protect one “thinking zone” per day

Decision fatigue kills higher‑order thinking first. By mid‑afternoon, deep thinking about pathophysiology is gone. That is normal.

Plan one 20–30 minute protected “thinking zone” when your brain is still workable. For most students: immediately after rounds / before lunch, or early evening.

In that block, you pick:

- One interesting patient or question from the morning.

- One source: UpToDate, a short review article, or a textbook section.

- One output: a half‑page synthesis, or 5 flashcards.

You are not “reading around every patient.” That fantasy is how people burn out. You are doing one targeted, cognitively meaningful piece of work per day. That keeps your brain sharp for exams without constant self‑criticism.

5. Social Decisions: Scripts Save More Energy Than You Think

This is the domain almost no one talks about explicitly, but it quietly drains students ruthlessly.

You are constantly deciding:

- When is it safe to ask a question?

- How honest should I be about not knowing?

- Do I stay to help, or is that “too eager”?

- Do I tell my resident I need to leave for an appointment?

If you improvise every time, you will be exhausted. So you pre‑load scripts and personal rules.

Script 1: “I need help but do not want to sound clueless”

Use a consistent sentence frame. For example:

- “I am not completely sure about the next step for X. I was thinking Y because Z. Is that reasonable or am I missing something key?”

This does three things:

- Admits uncertainty without signaling helplessness.

- Shows prior thought.

- Forces you to commit to a preliminary plan.

You are no longer deciding how to phrase it fresh every time. You plug your content into the template.

Script 2: “I need to leave on time without looking disengaged”

You should not be re‑inventing this weekly.

- “I wanted to let you know I have to leave by [time] for [brief reason]. I will make sure [task A and B] are done before I go. Is there anything else high‑priority you would like me to finish?”

Done. Professional, respectful, and finite. You do not start a half‑hour explanation ceremony every time.

Script 3: When you do not know an answer on rounds

Do not burn mental energy on shame spirals. Use a fixed response:

- “I am not sure. My guess would be [X] because [Y]. I can look it up and report back this afternoon.”

That is it. You are not negotiating your worth in real time.

Personal social rules to kill indecision

Set simple rules ahead of time:

- “I will ask at least one question per day on rounds, even if I feel awkward.”

- “If I am 70% sure about my plan, I will state it instead of staying silent.”

- “I will not stay later than 30 minutes after my senior leaves unless explicitly asked.”

These rules turn dozens of anxious micro‑decisions into automatic behavior.

You are not trying to be “perfectly calibrated.” You are trying to be consistent and conserve bandwidth.

6. Self‑Regulation: Guardrails So Your Brain Has Something Left

Now we get to the unglamorous stuff. Sleep, food, movement. Everyone knows they matter. Most students still handle them reactively.

Decision fatigue makes self‑care decisions especially fragile. At 9 PM, “Should I go to the gym?” is almost always answered with “No.”

So you stop making those decisions daily.

The “Default Week” method

You build a default clinical week. Not a fantasy schedule. A realistic baseline you stick to unless something unusual happens.

Example for an inpatient medicine rotation:

Sleep:

- In bed by 10:30 PM on weekdays

- Wake 4:50–5:00 AM

- One 20‑minute nap max post‑call if needed

Food:

- Fixed breakfast at home (do not decide daily)

- Carry the same two snacks every day (nuts + bar, for example)

- Aim for lunch before 2 PM, non‑negotiable unless acutely unsafe

Movement:

- Short walk (10–15 minutes) after sign‑out or after getting home 3 days/week

- 1–2 actual workouts per week if possible, not 5

You write this out literally as “Default Medicine Week.” Tape it above your desk.

Then you stop asking “Should I…?” about these items daily. You do the default unless there is a concrete reason not to.

Non‑negotiables vs. negotiables

When you are fried, everything feels optional. You need a hierarchy.

Non‑negotiable on most rotations:

- Minimum 6 hours time in bed.

- Some form of calories before noon.

- Having at least one support touch‑point per week (friend, partner, therapist).

Negotiable:

- Social events that start after 9 PM.

- Extra shifts “just to watch a cool case” when you are already at the edge.

- Perfectionist notes that take 40 minutes instead of 20.

Write out 3–4 non‑negotiables for yourself. Real ones. Not “I will always get 8 hours.”

7. A Daily Framework You Can Actually Use

Let me package this into a single system. Think of it as a “focus‑preservation protocol” you run each day.

Night before (5–7 minutes)

- Look at tomorrow’s schedule (rounds, OR cases, clinics).

- Choose:

- 3 patients to know cold

- 2 topics to likely read about (flexible)

- 1 behavior to practice (e.g., “state my plan before asking for help”)

- Confirm your wake time and transport plan (no morning surprises).

- Prep your bag: snacks, water bottle, pocket notebook, pens, badge.

You go to bed with the day already partially decided.

Morning (on arrival, 2 minutes)

On a fresh note or index card:

- Write: “Today’s 3–2–1” (patients/topics/behavior).

- Rewrite your preround checklist if you do not have it memorized yet.

- Glance at your “Default Week” rules.

That is your operating manual for the day. Not your inbox. Not the EMR.

During the day

- For each patient: run your fixed checklist.

- After rounds: mark one “thinking topic” from what came up. That is your learning target later.

- For social doubts: use your pre‑decided scripts, not new apologies.

When unexpected stuff hits—code, complicated family meeting, new admission swarm—you let your constraints do their job. You may not get to your full study plan. The non‑negotiables still stand.

Evening (15–30 minutes structured)

Minimum viable study block:

- 5–10 questions or one short reading on your earlier “thinking topic.”

- Jot 3–4 key points in a notebook or Anki.

Then:

- 5 minutes to write:

- One thing you did well.

- One thing that bothered you.

- One thing you will try differently tomorrow.

That reflection is not sentimental. It is data. You adjust your scripts and rules based on patterns.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Night Before: Plan 3-2-1 |

| Step 2 | Morning: Checklist & Anchors |

| Step 3 | Daytime: Execute Checklists & Scripts |

| Step 4 | Evening: Minimal Study Block |

| Step 5 | Brief Reflection & Adjust |

8. Exam Performance: Why This Matters More Than Another Resource

Most students try to solve poor shelf performance with more content: new Qbank, new video series, new outline book.

If you are cognitively shot by 8 PM most days, adding more content is pointless. You do not have a resource problem. You have an energy‑allocation problem.

Look at what this framework does for exams:

- Your brain practices forming assessments and plans daily (because you state your plan instead of staying silent). That maps directly to exam stems.

- Your one “thinking topic” a day accumulates to 5–6 high‑yield focused reviews per week. That is 20–25 per month. Without hour‑long marathons.

- You compress study time but improve quality. Fewer half‑awake, low‑retention sessions.

And by reducing decision fatigue, you reduce the chronic low‑level stress that quietly destroys working memory and recall. Which matters a lot during 2+ hour shelf exams.

On exam day itself, you can use the same philosophy:

- Pre‑select your break strategy (when you will pause, what you will eat).

- Use a fixed question triage rule:

- Answer straightforward ones immediately.

- Flag and skip time‑sink questions quickly.

- Do not reconsider your first pass unless you see clear contradictory information later.

Same concept. Fewer in‑the‑moment choices. More energy for actual reasoning.

9. When Things Are Already Slipping: Red Flags and Reset Moves

If you are reading this mid‑rotation and already feel wrecked, do not try to implement everything. You prioritize.

Red flags that decision fatigue is tipping into burnout

- You start dreading not just the rotation, but medicine in general.

- You cannot remember key events from your day by 9 PM.

- You snap at people who normally would not bother you.

- You are making avoidable clinical mistakes (missing abnormal vitals, wrong patient in the EMR).

- You find yourself thinking, “I do not care what happens with this patient.”

When those patterns show up consistently, you need an actual reset. Not just “a better planner.”

Three‑step micro‑reset (over 48–72 hours)

Shrink your commitments

- Drop non‑essential extracurriculars for that week.

- Reduce your study target to a bare minimum (e.g., 5 questions/day, no more).

- Tell yourself explicitly: “I am switching into damage‑control mode for 3 days.”

Reinforce 2–3 hard non‑negotiables

- Bedtime cut‑off.

- One consistent meal.

- One support check‑in (friend, co‑student, mentor).

Loop in one person on your team

- You do not need to spill your entire mental health history.

- Simple: “I am feeling more run‑down than usual and I am worried about missing details. I am tightening my checklists, but please let me know if you spot any blind spots.”

Most decent residents and attendings have been there. And the ones who mock that are not role models you should be internalizing anyway.

If functioning is really impaired—persistent anhedonia, significant sleep change, intrusive thoughts, self‑harm ideation—you treat that as a medical problem, not a character flaw. Get professional help. That is not weakness. That is insight.

10. Putting It All Together

Decision fatigue on clinical rotations is not going away. The system is badly designed for cognitive conservation.

But you can stop playing on “hard mode” by default.

Lock in these core moves:

Pre‑decide your structures.

Two daily anchors, 3–2–1 priorities, a fixed preround checklist, and a default weekly routine remove dozens of useless micro‑decisions.Use scripts and rules in social situations.

Do not improvise your way through every question, request, or conflict. A handful of well‑crafted phrases and personal rules will save more mental energy than yet another productivity app.Protect a small amount of high‑quality thinking each day.

One targeted learning topic, one brief reflection, and one honest self‑check beat scattered, guilty, low‑yield “studying” every time.

You are not weak for feeling worn down by constant choices. You are human. Smart structure is not optional in this environment. It is survival equipment.