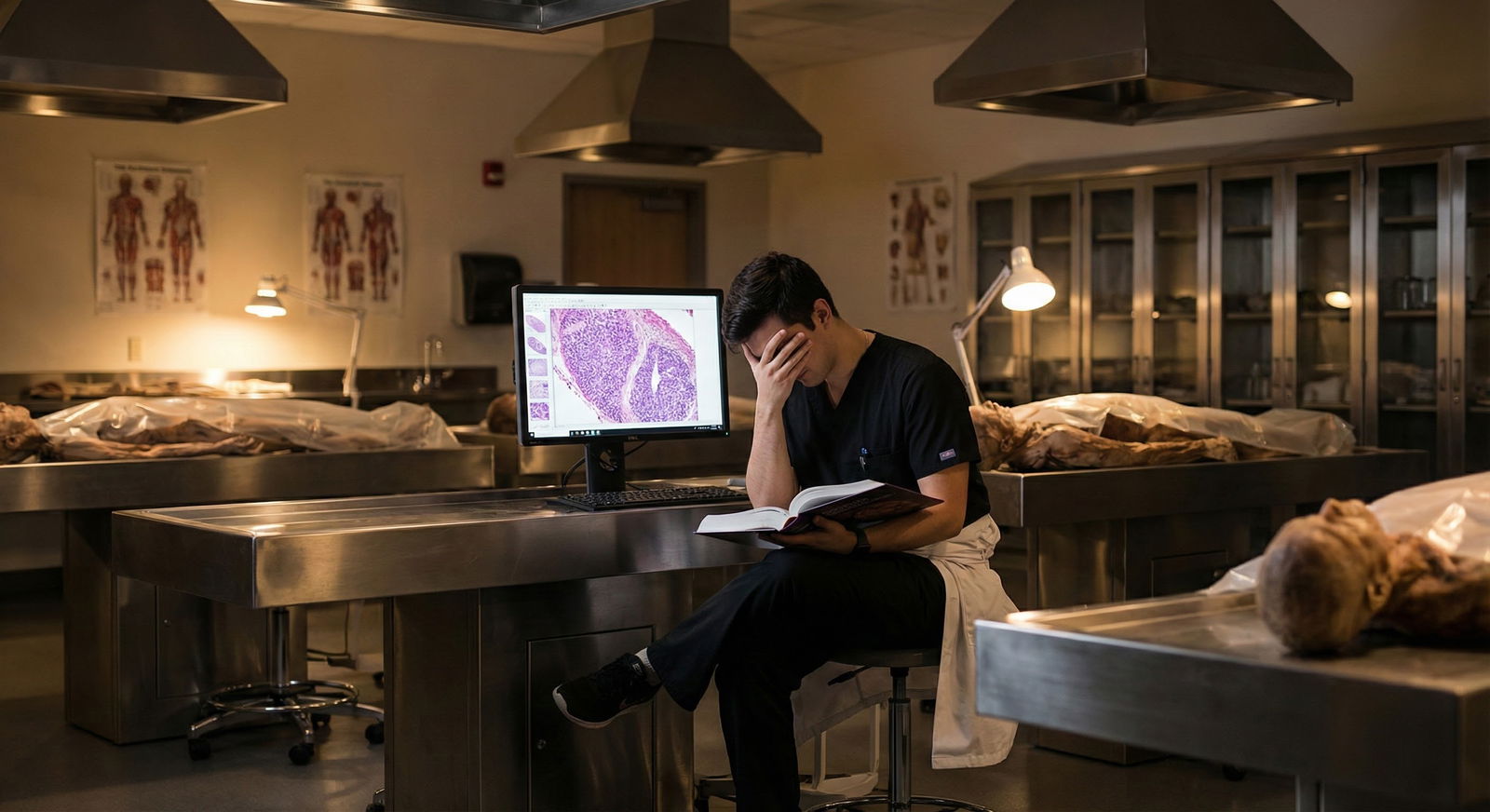

It is 1:37 a.m. Two days before your exam block. You are on your third cup of coffee, staring at the same Anki card you have seen nine times this week. You are not absorbing anything. You are not exactly sad. You are not exactly panicked. You are just…flat. And you are asking yourself a question that far too many medical students whisper and almost none say out loud:

“Is this burnout? Or am I actually depressed or anxious?”

Let me break this down very specifically, because muddling these three is one of the fastest ways to stay unwell for months longer than you need to.

Why This Distinction Actually Matters

People in med school throw around “burnout” like a catch‑all label.

“I’m so burned out.” “Clerkship has me burned out.” “Step studying burned me out.”

Sometimes that is true. Sometimes it is a euphemism because “I am depressed,” or “my anxiety is out of control,” feels too heavy, too stigmatizing, or too permanent.

Here is why you need to get this right:

- Burnout is fundamentally a work‑related syndrome. Change the workload, autonomy, support, and rest, and it often improves.

- Major depression is a medical illness that can kill you if missed.

- Anxiety disorders can wreck your functioning, sleep, and physical health even if your grades stay intact.

And exams, clerkships, and residency applications do not care how you feel. They will keep coming. So the sooner you know which enemy you are fighting, the better you can choose the right tools.

The Core Definitions – Plain, Clinical, and Applied to Med School

Let us start cleanly with what we are actually talking about.

1. Burnout – The Work‑Linked Triad

Classic burnout (Maslach’s model) has three pillars:

- Emotional exhaustion – feeling drained, used up, “I have nothing left to give.”

- Depersonalization / cynicism – “These patients are annoying,” “This is all pointless,” “Everyone here is faking.”

- Reduced personal accomplishment – “I am not good at this,” “Nothing I do matters.”

The key: Burnout is tied tightly to role and environment.

In med school terms:

- Your symptoms spike around:

- Studying

- Rounds

- Emails from admin

- Call schedules

- Evaluations

- But you may still:

- Enjoy time with friends (when you manage to see them)

- Feel some joy in hobbies (if you can access them at all)

- Light up briefly when you get to do something meaningful (a good patient interaction, a procedure, teaching a junior)

Remove or reduce the stressor — a break, a lighter rotation, a supportive attending — and your baseline often lifts. Not magically, but noticeably.

Burnout usually says:

“I hate this system, and it is draining me.”

2. Major Depressive Disorder – Pervasive and Generalized

Depression is not just “really tired” or “down about school.”

Clinically, think:

- At least 2 weeks of:

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day

OR - Markedly diminished interest/pleasure (anhedonia)

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day

- Plus 3+ of:

- Sleep issues (insomnia or hypersomnia)

- Appetite/weight change

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Psychomotor agitation/retardation

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive/inappropriate guilt

- Poor concentration or indecisiveness

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide

Med‑school reality version:

- You do not just dread Anki; you also:

- Stop caring about the hobbies you used to love.

- Feel emotionally numb even when with close friends or family.

- Have this constant internal voice: “I’m a failure,” “Everyone else is managing,” “They’re going to figure out I’m a fraud.”

- The low mood or emptiness is there on post‑exam weekend, during vacation, at home, on a random Wednesday night. It is not just attached to school tasks.

- You can be on a light elective and still feel crushed.

Depression usually says:

“I hate myself, and the world feels drained of color.”

3. Anxiety Disorders – Hyperarousal, Fear, and Constant Threat

Anxiety in med school gets normalized. People brag (insanely) about being “neurotic” and “high strung,” as if that is a badge of honor.

Clinically, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and other variants share some features:

- Excessive worry that is:

- Hard to control

- Disproportionate to the situation

- Spanning multiple domains (grades, future career, health, relationships)

- Physical arousal:

- Racing heart

- Sweating

- GI issues

- Tremor

- Muscle tension

- Shortness of breath

- Behavioral patterns:

- Avoidance

- Reassurance seeking

- Procrastination that is actually fear in disguise

Med‑school flavor:

- You are “studying” but really doom‑scrolling Reddit because opening UWorld makes your chest tighten.

- Before every quiz you have nausea, palpitations, maybe even near‑panic.

- You cannot fall asleep because your brain is running “What if I fail Step? What if I never match? What if I embarrass myself on rounds?” on loop.

- Even on breaks, your mind manufactures threats to chew on.

Anxiety usually says:

“I am not safe. Something terrible is coming. And it will be my fault.”

The Overlap: Why Med Students Get Confused

This is why you are confused: these syndromes share symptoms.

Fatigue. Poor concentration. Irritability. Sleep disruption. All three can give you those.

And med school pours gasoline on everything: long hours, inconsistent sleep, constant evaluation, no real control, plus a culture that still quietly stigmatizes saying, “I am not okay.”

Let’s organize the overlap and the differences clearly.

| Feature | Burnout | Depression | Anxiety |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main driver | Work/role stress | Global mood/biologic factors | Fear/worry, hyperarousal |

| Mood outside of school | Often better | Still low or empty | Still worried or keyed up |

| Interest in hobbies | Can enjoy if energy available | Markedly reduced/absent | Can enjoy, but mind drifts to worries |

| Self‑view | “System is broken” | “I am broken / worthless” | “I am at risk / will fail” |

| Sleep | Often due to workload/schedule | Early AM waking or oversleeping | Difficulty falling asleep, racing mind |

| Core emotion | Exhaustion + cynicism | Sadness / emptiness | Fear / tension |

If you only memorize one thing from that table:

Burnout is anchored to work, depression to mood/self‑worth, anxiety to threat/worry.

Specific “Tells” That Push You Toward One Diagnosis

Let me be more concrete. These are patterns I see over and over in med students.

Clues for Predominant Burnout

You say or think things like:

- “If I just had a week off, I could reset.”

- “I still love medicine, I just hate how we are being trained.”

- “When I am away from school, I feel like myself again. Then I come back and it all crashes.”

Behaviorally:

- Your energy tanks when you open your inbox or schedule.

- You become sarcastic, cynical, eye‑rolly about patients, staff, and administration.

- You do the bare minimum to pass, not because you are lazy, but because you feel empty and detached.

- You fantasize about quitting medicine or switching careers not out of panic or sadness, but as an escape from a toxic ecosystem.

But: You still laugh at a show, enjoy a dinner, get absorbed in a hobby on the rare occasions you allow yourself to do those things. The capacity for pleasure is there. It is just buried under chronic stress.

Clues for Predominant Depression

You recognize yourself in statements like:

- “Even when I am off, I feel nothing.”

- “I do not recognize myself anymore.”

- “I know I should be happy about [good thing], but I just feel flat.”

You notice:

- You stop responding to texts, not just because you are busy, but because it feels pointless or too draining.

- You wake up already tired, with a heavy or hollow feeling in your chest, independent of that day’s schedule.

- Self‑talk is brutal: “Everyone else is handling this better. I am weak. I am a failure.”

- You have thoughts like, “If I got hit by a car and did not have to do this anymore, that might be a relief.”

That is not “normal med student stress.” That is a red flag.

Clues for Predominant Anxiety

You catch yourself in cycles like:

- Ruminating for 30–60 minutes at night about scenarios that have a 1% chance of happening.

- Replaying conversations with attendings, convinced you said something wrong.

- Checking your grade portal or email multiple times a day “just in case.”

- Using “studying” as a word for sitting in front of material while your brain is actually arguing with catastrophic fantasies.

Physically:

- You feel keyed up even on weekends.

- You get GI symptoms, headaches, or tachycardia around tests or OR days.

- You sometimes have full‑blown panic: short of breath, chest tight, pins and needles, “I’m going to faint / die / lose control.”

A Simple Mental Algorithm: What Am I Actually Dealing With?

You want something actionable. So here is a mental flow that maps out what I would walk through with a student in clinic.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Notice distress or dysfunction |

| Step 2 | Consider burnout |

| Step 3 | Predominant burnout, screen for depression/anxiety as well |

| Step 4 | Consider depression, assess severity & safety |

| Step 5 | Consider anxiety disorder(s) |

| Step 6 | Consider other causes: sleep, substances, medical issues |

| Step 7 | Symptoms mainly during school/work tasks? |

| Step 8 | Persistent low mood or loss of interest? |

| Step 9 | Still enjoy non-school activities? |

| Step 10 | Excessive worry, fear, or panic? |

Notice I am not saying “either/or.” Burnout, depression, and anxiety love to travel together. The algorithm just helps you figure out what is leading the parade.

If you are burned out long enough, you can absolutely become depressed. Chronic anxiety can exhaust you into a gray, depressed state. Depression can make you perform worse, which feeds anxiety and burnout. It is not clean.

But for treatment, it helps to know:

What is the primary fuel source right now? Work conditions? Internal mood? Fear circuitry?

Stress, Burnout, Depression, Anxiety: Not the Same Thing

Students often confuse baseline stress with everything else. That muddies decisions about when to seek professional help versus when to change study habits or set boundaries.

This is the spectrum, roughly:

Normal stress

Feeling pressured or worried during exams or busy rotations, but:- You still find meaning.

- You still feel like yourself.

- You can recover with rest.

Burnout

Chronic workplace/role stress that is not managed. You:- Feel emotionally drained.

- Develop cynicism.

- Feel less effective. But your capacity for joy outside of this role is mostly intact.

Depression/anxiety disorders

Internal states that:- Outlast external stressors.

- Spread into almost every domain of your life.

- Impair your ability to function, connect, and care for yourself.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| High Stress | 80 |

| Burnout | 45 |

| Depression | 25 |

| Anxiety Disorders | 30 |

Those percentages are ballpark from multiple studies over the last decade. The exact numbers vary, but the pattern holds: high stress is nearly universal; burnout is common; depression and anxiety disorders are disturbingly prevalent.

Concrete Self‑Checks You Can Do This Week

You do not need a 40‑item scale to start clarifying this. Try these prompts honestly.

“If med school magically disappeared for 1 month — no responsibilities, financial security guaranteed — what would my emotional state likely be?”

- “Relief, then probably some genuine enjoyment.” → Burnout‑leaning.

- “I might still feel heavy, disconnected, or numb.” → Screen for depression.

- “I would spend the whole month worrying about falling behind and ruining my future.” → Anxiety‑leaning.

“When was the last time I felt genuinely excited or absorbed in something non‑school‑related?”

- If you can name something in the last 1–2 weeks, your pleasure circuitry still works.

- If you have to go back months, that is more concerning for depression.

Sleep log for 7 days:

- Trouble falling asleep with racing thoughts → anxiety pattern.

- Waking 3–4 a.m. with early‑morning dread → classic in depression.

- Fragmented purely because of call, night shifts, or library closing times → burnout / external factors.

“How do I talk to myself when I mess up?”

- “This system is messed up; of course I missed that.” → Burnout lens.

- “I am incompetent, I do not belong here.” → Depressive self‑schema.

- “If I mess this up, I will never match and my life is over.” → Catastrophic anxiety.

Write your real answers down. You will see the patterns in black and white, not just in your head.

What To Actually Do: Different Levers for Different Problems

I am going to be blunt here: you cannot “self‑care” your way out of major depression or severe anxiety. And no amount of SSRIs will fix a toxic training environment that is burning you to the ground.

So the intervention has to match the problem.

If Burnout is Primary

Your targets are systemic and behavioral.

You need to modify the context:

Lighten the load where possible:

- Negotiate rotation schedules where that is permitted.

- Use pass/fail strategically; stop chasing honors at the expense of your brain.

- Say no to extra “opportunities” that are really unpaid labor in disguise.

-

- Hard cutoffs for daily studying. Your brain is not a 24‑hour service.

- Separate “work zone” and “non‑work zone” physically if you can.

- Protect time that is deliberately non‑productive. Not as a luxury. As treatment.

Re‑inject meaning:

- Seek out even small patient interactions or tasks that remind you why you came to medicine.

- Find micro‑mentors: a PGY‑2 who is not miserable, an attending who remembers your name and does not humiliate people.

And yes, therapy can help with burnout, not by “fixing you” but by helping you respond to a broken system without shattering.

If Depression is Present

You are in a different category. You need clinical evaluation. Not eventually. Now.

Options that actually work:

Evidence‑based psychotherapy

- CBT, IPT, or ACT, depending on your style and availability.

- Focused on:

- Challenging the “I am worthless” narrative.

- Rebuilding behavioral activation: small, structured steps back into life.

- Identifying perfectionism and self‑criticism that med culture amplified.

Medications

- SSRIs or SNRIs are first‑line.

- Medication does not erase external stress but can lift the floor enough that you can engage with your life again.

- This is not moral failure or “weakness.” It is the same logic as treating hypertension in a high‑stress job.

Safety planning

- If you have passive thoughts about dying, bring them up explicitly.

- If you have active suicidal thoughts, a plan, or access to means: you need urgent care. That might mean calling a crisis line, going to an ED, or telling your dean or a trusted attending. I have seen too many students try to white‑knuckle through “just until after exams.” Some never make it that far.

If Anxiety is Leading

Your main levers:

-

- Identifying and dissecting catastrophic thoughts.

- Exposure instead of avoidance:

- Gradual, structured practice doing the things you fear (presenting on rounds, starting questions earlier instead of procrastinating).

- Learning to tolerate physiological anxiety without spiraling.

Skills that are not fluff:

- Consistent sleep and wake times (yes, even in clerkships as much as you can).

- Brief, repeated relaxation practices (breathing, muscle relaxation) used like “reps,” not one‑off tricks.

- Focused, time‑bound study blocks to contain worry.

Medications when indicated:

- SSRIs/SNRIs for generalized or persistent anxiety.

- Avoid relying on benzos as your main solution; they are short‑term tools with long‑term consequences.

How To Talk About This With People Who Can Actually Help

One of the biggest barriers I see is students not knowing how to say what they are experiencing in a way that gets taken seriously.

You walk into a dean’s office and mumble “I am kind of burned out,” and they nod, say everyone is stressed, and send you back out with a wellness flyer.

Try this instead, with your school counselor, a physician, or therapist:

Be specific with function:

- “I have not been able to complete assignments on time for the last 3 weeks.”

- “I am sleeping 4–5 hours a night despite trying to wind down by 10 p.m.”

- “I skipped two days of clinic because I could not get out of bed.”

Name your internal state:

- “I feel empty all the time, even outside of school.”

- “I am having intrusive thoughts about not wanting to be alive.”

- “I have panic‑like episodes before every exam.”

Ask for concrete support:

- “I need help determining if this is burnout or depression.”

- “I want a referral to a mental health professional with experience in medical trainees.”

- “I need to discuss a temporary schedule modification or leave.”

You are not asking for a character reference. You are describing symptoms and impairment. Just like you do for patients.

When Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety Stack

Worst‑case scenario — and not rare — is that all three are present.

Picture this:

- Longstanding perfectionism + high‑stakes environment → chronic anxiety.

- Chronic anxiety + never feeling “good enough” → depressive thoughts.

- All of this in a system with no brakes, long hours, constant evaluation → full‑blown burnout.

In that case:

- You still address the system where possible (burnout).

- You still treat the mood disorder (depression).

- You still retrain your fear circuitry (anxiety).

There is no prize for guessing the single “right” label. The goal is not diagnostic purity. The goal is: You functioning as a human who happens to be in medicine, not as an exhausted machine that happens to be still passing exams.

Practical Red‑Flag Thresholds: Do Not “Wait and See”

Here are lines you should not cross without involving a professional:

- Thoughts of wanting to die, being better off dead, or not caring if you wake up.

- Any planning about how you might hurt yourself, even if you tell yourself you “would never do it.”

- Inability to attend required school activities for more than a few days because of emotional state.

- Panic attacks that are recurrent and making you avoid key academic situations.

- Neglect of basic self‑care: not showering for days, barely eating, losing significant weight unintentionally.

If any of those are present, this is no longer a “maybe I am burned out” question. This is a health issue that warrants real, immediate intervention.

FAQ – Exactly 6 Key Questions

1. Can burnout turn into “real” depression, or are they totally separate?

Burnout absolutely can evolve into major depression if it is severe and prolonged. Chronic emotional exhaustion, feeling ineffective, and being trapped in a hostile or unsupportive environment can slowly erode your mood, self‑worth, and biology. You start burned out — mostly work‑tied — and months later you are numb, hopeless, and not enjoying anything, even outside medicine. At that point, you are not just “tired of school”; you likely meet criteria for depression and need treatment, not just time off.

2. How do I know if what I feel is just “normal” med‑school stress and not something pathological?

Look at pattern, duration, and spillover. Normal stress fluctuates with exams and rotations, but you still feel basically like yourself, can recover with rest, and have some joy in life. Burnout, depression, and anxiety disorders persist beyond peak stress, bleed into multiple areas of your life, and significantly impair your functioning or self‑care. If friends are saying “You’re not yourself,” or you are consistently unable to do things you previously managed, you have crossed from “normal stress” into something that deserves clinical attention.

3. My classmates are also exhausted and cynical. Does that mean we are all burned out?

Not necessarily, but probably many are to some degree. Burnout is not defined by one bad week or a few sarcastic comments. It is defined by a sustained pattern of emotional exhaustion, cynicism toward patients or the system, and feeling ineffective, driven by chronic work stress. A whole cohort can be burned out when the environment is consistently abusive, chaotic, or unsupportive. The fact that it is common does not make it benign. If anything, it means you should take it more seriously, not less.

4. What if I am functioning “well” academically? Could I still have depression or anxiety?

Yes. Grades are a terrible proxy for mental health. I have seen students with top decile scores who could not sleep, had daily panic attacks, or were actively suicidal. High achievement can mask severe internal distress because you can still perform on paper while burning out internally. If you are using performance to argue yourself out of seeking help — “I can’t be that bad, I’m still doing well” — you are using the wrong metric. Mental illness is about suffering and impairment, not just GPA.

5. Is taking a leave of absence a sign I am not cut out for medicine?

No. That narrative is toxic and simply wrong. Plenty of excellent physicians took time off in med school or residency for health, mental health, family crises, or other serious reasons. Taking a leave when you need it is a sign of insight and responsibility, not weakness. The students who worry me more are the ones who refuse any pause, grind themselves into the ground, and end up hospitalized or leaving medicine altogether because they waited until there was nothing left to salvage.

6. Who should I actually talk to first if I am worried it is more than burnout?

Start with someone who has two key traits: confidentiality and some power to connect you with care. That might be your school’s mental health service, a campus counseling center, a trusted attending or resident who will not gossip, or your own primary care doctor. Spell out specific symptoms and how long they have lasted. Ask explicitly for a mental health referral if they are not a mental health clinician themselves. If you are in crisis (suicidal thoughts with intent or plan), go to the nearest emergency department or call your country’s crisis line. Do not wait for “a better time” in your exam schedule.

Key points to keep in your head:

- Burnout is mainly about your relationship to work; depression and anxiety are about persistent internal states that follow you everywhere.

- If your misery evaporates on real breaks, burnout is likely central; if it follows you home and into weekends, screen aggressively for depression and anxiety.

- You are allowed — and expected, as a future physician — to treat your mental health with the same seriousness you would insist on for a patient.