The most preventable mistakes in procedures do not come from ignorance. They come from unobserved mind states.

You can know every step of a central line or colonoscopy cold and still hurt someone if your attention is fragmented, your ego is driving, or you are silently rushing. Traditional checklists catch equipment and steps. They almost never catch the operator’s mind.

This is where a cognitive, mindfulness-based checklist belongs: built into your procedural routine the same way time-outs and sterility checks are. Not as incense-and-yoga fluff. As a hard, practical safety tool.

Let me break this down specifically.

Why Mindfulness Belongs in the Procedure Room

Mindfulness in medicine has been marketed like a wellness perk. That is backward. During procedures, it is a performance and safety requirement.

On any given procedure list, you are juggling:

- Technical complexity

- Institutional time pressure

- Learners watching

- Patient vulnerability (often sedated, voiceless)

- Your own fatigue, mood, and cognitive load

Under that stack, three cognitive failure modes show up constantly:

- Tunnel attention – Over-focusing on one problem (a tricky wire, a bleeder) and losing track of the whole.

- Autopilot – Running a “script” you have done a hundred times while your mind is elsewhere.

- Cognitive flooding – Anxiety, annoyance, or shame taking over your working memory.

All three are detectable—if you look. And they are modifiable in real time with specific micro-interventions that take seconds.

That is what a cognitive checklist does: forces you to look.

The Core Model: Before–During–After Mind States

We will structure the checklist around three phases:

- Pre‑procedure: “What mind am I bringing into this room?”

- Intra‑procedure: “Where is my attention right now?”

- Post‑procedure: “What did this case do to my mind and ethics?”

Each phase has a small set of questions and micro-practices. This is not a 20‑minute meditation. The whole thing adds maybe 60–90 seconds total once you have it wired in.

To keep it concrete, I will use an example you know: ultrasound-guided internal jugular central line. But the structure generalizes to bronchs, LPs, ERCPs, EP ablations, plastics cases—pick your poison.

Part 1 – Pre‑Procedure: A 30‑Second Cognitive “Time‑In”

You already do a procedural time‑out: correct patient, site, consent, allergies. That is for the system.

You need a parallel time‑in: correct cognitive state, intention, attention anchors. That is for you and for the patient’s safety.

A. The 5‑Question Cognitive Check

Right before you scrub or just before entering the room, run these five questions. Silently, in order.

“What is my primary intention?”

Not what CPT code, not what teaching objective. One sentence in your own head:- “Place a safe right IJ line with minimal trauma, first attempt if possible.”

- “Perform a complete colonoscopy, avoid unnecessary discomfort, no shortcuts.”

If the answer is anything like “Finish this fast so I can get to sign-out” or “Show the intern how slick I am,” notice that. You do not need to judge it. You do need to override it:

“My intention is safe, respectful care for this patient, with appropriate teaching.”“What is my current cognitive load?”

Quick rating: Low / Moderate / High.- High = you are holding three unresolved problems, six pages, and two texts in your head.

- Moderate = normal list pressure, but nothing acute.

- Low = rare, but it happens.

If you are High, you do one thing: consciously park everything noncritical. Literally tell yourself:

“For the next 20 minutes, this line is my only job. The rest can wait.”

That single cognitive boundary cuts error rates far more than another round of “be careful.”“What is my emotional state?”

Pick the dominant signal: calm / tense / annoyed / sad / keyed‑up.

Ignoring this is how anger and ego end up driving your hands.If it is anything other than calm or neutral, name it precisely:

- “I am irritated from that page fight with ICU.”

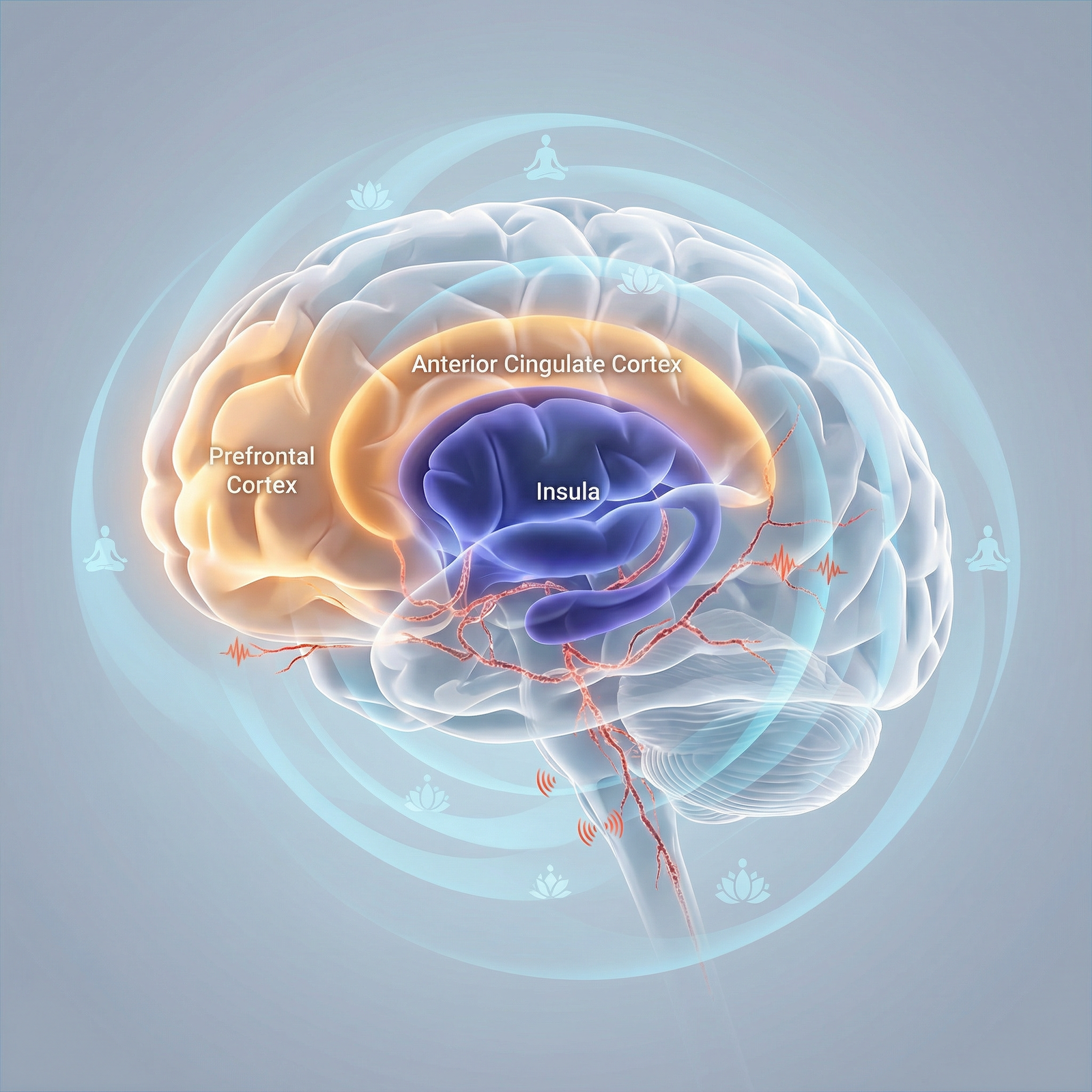

- “I am anxious about that bad outcome yesterday.”

Labeling an emotion in words moves it out of the reflex centers and into prefrontal territory. That buys you control.

“Am I about to rush?”

This is binary. Yes or no.

If “Yes,” you insert a forced speed reset:

“I will move at my standard pace. If this cannot be done safely at that pace, I will say so out loud.”That sentence matters for ethics: you are pre‑committing not to collude with institutional pressure over safety.

“What does this specific patient need from my attention?”

Not generic “be careful.” Something procedural and human:- “She is coagulopathic. Needle passes must be absolutely minimal.”

- “He is terrified and awake. I will narrate each step in simple language.”

This locks your mind onto this body, this story. It counters the depersonalization that creeps in by case 7.

B. A 3‑Breath Reset Protocol

Once you run the five questions, do exactly three slow breaths. Not ten. Not “a few.”

On the inhale, silently: “In.”

On the exhale, silently: “Here.”

That is it.

Three cycles is about 15–20 seconds. I have watched high-volume endoscopists and trauma surgeons do this at the scrub sink. Nobody notices. But your autonomic tone shifts just enough to widen your attentional field.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Enter procedure room |

| Step 2 | Cognitive time in |

| Step 3 | Park other tasks mentally |

| Step 4 | Proceed |

| Step 5 | 3 breath reset |

| Step 6 | Start technical time out |

| Step 7 | High cognitive load |

Part 2 – Intra‑Procedure: A Cognitive Checklist in Motion

Once you are in the case, the checklist must be quick and embedded. You cannot drop instruments to meditate.

Think of it as three repetitive loops:

- Situation loop – “Big picture”

- Micro‑attention loop – “Where is my focus right now?”

- Ethical loop – “Is how I am behaving aligned with my values?”

A. The 60‑Second Situation Loop

Roughly every minute or at natural breaks (wire in, needle out, scope at cecum), you do a rapid 4‑point scan:

Field – “Is what I am seeing consistent with my mental model?”

- Is the IJ compressible and lateral to carotid as expected?

- Is the colon mucosa appearance matching a clean prep and normal anatomy?

If not, you stop and re‑orient: more ultrasound sweeps, rethink landmarks, ask for help.

Vitals / Monitors – “Any deviation I am ignoring?”

Not just numbers. Pattern. Rising CO2? Slowly dropping BP you have been hand‑waving? Someone holding their breath in MAC sedation because they are afraid?Team bandwidth – “Is my team with me, or mentally gone?”

Glance and ask:- “Nurse, still ok on sedation and vitals?”

- “Tech, do you have what you need for the next step?”

This invites them back into shared attention. Ethically, it also de‑isolates responsibility. You are the operator, not the only mind in the room.

Time reality check – “Have I let time pressure back in?”

If you catch yourself thinking “I am behind, I am behind,” say internally:

“I will finish when the case is safely done. Not before.”

That whole loop is 5–10 seconds when practiced. Initially, you can literally set a timer on your watch every 3–4 minutes until it becomes automatic.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Tunnel vision | 35 |

| Autopilot | 25 |

| Emotional flooding | 15 |

| Rushing | 20 |

| Team disengagement | 5 |

B. Micro‑Attention: The Anchor–Expand Cycle

Mindfulness during procedures is not “always aware of everything.” That is impossible and useless. It is the deliberate oscillation between:

- Narrow, technical focus

- Broader, situational awareness

You build that as an Anchor–Expand cycle.

Anchor – For the next 10–20 seconds, you choose a primary sensory anchor:

- The ultrasound screen and your non‑dominant hand pressure

- The tip of the scope and mucosal detail

- The tactile feel of the needle passing through layers

While anchored, you commit to full immersion in that micro‑task. If other thoughts intrude (“why did GI not call back”, “this intern is slow”), notice and drop them. There is no room for them at that stage.

Expand – As soon as you finish that micro‑segment (wire in vessel, needle out, lesion biopsied), you deliberately un‑zoom:

- Quick sweep of room, monitors, patient face (if visible).

- One conscious breath.

- One question: “Anything new I am missing?”

This is 2–5 seconds. Then back to anchor.

Without this oscillation, you either:

- Stay so locked on the “fun” technical bit that you miss slow vital drift, or

- Stay so keyed up on the whole situation that your fine motor work becomes clumsy.

Anchoring and expanding is what elite operators are doing intuitively. You can make it explicit and trainable.

Part 3 – Emotional and Ethical Micro‑Checks During the Case

Procedures push hard on ethics because the power imbalance is maximal.

The patient is often sedated or restrained, physically exposed, and entirely dependent on your judgment. You, under pressure, may slide into depersonalization, dark humor, or quiet cruelty without noticing. I have seen it. You probably have too.

A cognitive checklist that ignores this is incomplete.

A. Three Ethical Questions to Ask Yourself Mid‑Case

At some midpoint and again near the end, mentally ask:

“Am I speaking about this patient as a person or as a body part/problem?”

If you hear yourself say, “This is the obstructed colon in 12B,” consider correcting it in real time:

“Mr. S in 12B, obstructed colon.”

Small, yes. But it shifts the room culture.“If this patient could watch a full recording of my words and actions right now, would I be comfortable?”

Not “legal” comfortable. Ethically comfortable.

If not, you adjust. You stop the snide remark. You narrate what you are doing out loud. You apologize if you snapped at a nurse.“Would I want this exact technique and level of thoroughness used on me or my family member?”

This is a brutal but clarifying standard.

It stops the lazy “good enough” biopsy sampling. The “they are sick anyway” rationalization when you are tempted to be rough.

These questions do not slow the case down. They ride on top of your technical flow. But they sharply reduce moral injury—to you and to the patient.

B. Handling Emotional Flooding in Real Time

You will have cases that trigger you:

- A line on a patient who reminds you of a bad outcome

- A pediatric procedure when you are a new parent

- A complication unfolding in front of learners

If you feel your chest tightening, jaw clenching, or your thoughts going white‑noise, that is emotional flooding. Once flooded, your working memory and fine motor skills tank.

Here is the in‑case protocol:

Name it internally in one word.

“Fear.” “Anger.” “Shame.”

Labeling dampens the amygdala. It is not psychotherapy. It is cognitive first aid.Ground in one physical sensation for 3 seconds.

The feel of your feet in your shoes. The weight of the instrument in your hand.

While continuing the necessary, safe action.If safety is at risk, call a pause out loud.

“Let us pause for 10 seconds; I need to reassess.”

Then: take 2 deliberate breaths, scan field and vitals, re‑plan the next step.

Nobody competent will judge you for that. Any attending who does is modeling negligence, not excellence.If you realize you are beyond your bandwidth, say it:

“I need another pair of eyes on this. Call X.”

That statement is ethically heavyweight. It prioritizes the patient over your ego and the illusion of competence.

| Phase | Technical Checkpoint | Cognitive Checkpoint |

|---|---|---|

| Pre‑procedure | Site/time‑out | 5‑question cognitive time‑in |

| Needle entry | Correct landmarks | Anchor on sensation + breath |

| Mid‑procedure | Confirm progress (imaging) | 60‑second situation loop + ethical question |

| Complication | Follow algorithm | Emotional labeling + explicit pause |

| End of case | Dressings, documentation | Brief debrief + intention reset |

Part 4 – A Concrete Cognitive Checklist: Central Line Example

Let me put this into a full, real sequence so you can see how it looks in practice. Take a right IJ central line in the ICU.

Step 1: Outside the room (15–20 seconds)

Silently:

- “Primary intention: Place a safe right IJ line with single ultrasound-guided venipuncture, minimal attempts.”

- “Cognitive load: high, I just had 3 pages and a bad conversation.”

→ “For next 20 minutes, this is my only job.” - “Emotion: frustrated about consult delay.”

→ Name it: “Frustrated.” - “Am I about to rush? Yes, I am behind.”

→ “I commit to standard pace. If they push time, I will say it is unsafe.” - “This patient’s specific need: coagulopathic, low platelets. I must not repuncture blindly.”

Then 3 slow breaths: “In / Here” x3.

Enter room.

Step 2: During sterile prep and time‑out

While you scrub and gown:

- Anchor on the feel of the scrub, then expand: look at the patient’s face, monitors.

- During time‑out, mentally add your own: “This is Ms. J, 62, severe sepsis, needs reliable access. She is sedated but this is still her body, her neck.”

No spoken sermon. Just an internal correction against depersonalization.

Step 3: Ultrasound survey

Anchor: Ultrasound probe, image quality.

- “Does this IJ compress, sit lateral to carotid, any thrombus?”

- If not consistent with textbook mental model: you stop. Adjust plan (different site, consult).

Situation loop #1:

- Field: IJ anatomy reasonable

- Vitals: stable

- Team: “Everyone ready for needle? Nurse, happy with sedation?”

- Time: “I have the time I need for a single careful pass.”

Step 4: Needle insertion

Anchor hard:

- Right hand: needle angle and pressure

- Left hand: probe stability

- Eyes: tip of needle entering under ultrasound

Everything else drops.

As soon as flash is seen and guidewire is in:

Expand for 2–3 seconds:

- Monitor, patient, team visual scan

- One breath

- “Anything new?”

Then resume technical sequence.

Step 5: Mid‑case ethical check

While dilating or before final line suturing, run:

- “If Ms. J could watch a video of this entire interaction, including my tone with staff, would I be comfortable?”

- If the answer is “No, I snapped earlier,” you can even say aloud:

“Apologies for my tone earlier; this has been a hectic call. Thank you for keeping the room together.”

Ethically mature, zero loss of authority.

Step 6: If a complication hits

Suppose wire will not pass, or ultrasound image suddenly looks wrong.

You notice your heart jump, palms sweat.

In your head: “Fear.”

Feel your feet in your shoes for 2 seconds while maintaining a safe hold on instruments.

Then aloud:

“Pausing for 10 seconds to reassess wire position.”

Check ultrasound carefully. If you are not confident in vessel location, admit it to team and call for help.

You have just used mindfulness not as a relaxation tool, but as a circuit breaker against ego‑driven escalation.

| Category | Minor technical errors per 100 procedures | Self reported peak stress (0-10) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 14 | 8 |

| Month 1 | 11 | 7 |

| Month 3 | 9 | 6 |

| Month 6 | 7 | 5 |

Part 5 – Post‑Procedure: Micro‑Debrief and Ethical Integration

What you do mentally after the case determines whether you actually learn or just accumulate stress.

Again, this is not a therapy session. It is a 60‑second structured review.

A. The 3‑Column Debrief

Immediately after documentation or stepping out of the room, run three questions in your head or on a pocket card:

Technical – “One thing that went well, one thing I would adjust.”

- Well: “Single pass under ultrasound, good wire visualization.”

- Adjust: “Better communication before turning patient head; almost lost view.”

Cognitive – “What did I notice about my attention?”

- “Anchor–expand cycle felt solid until the consult call mid‑case.”

- “I drifted into autopilot during suturing and almost skipped a dressing check.”

Ethical / Emotional – “What did this case do to me?”

- “Felt defensive when nurse questioned line site. Next time, I will explicitly invite concerns.”

- “Image of her bruised neck is sticking with me; I need to acknowledge the emotional weight, not just brush it off.”

You are not writing an essay. Two sentences each. This is how reflective practice actually happens in a packed clinical day.

B. Intention Reset for the Next Case

Before you rush to the next procedure, take literally one breath and choose one sentence:

- “For the next case, I will pay particular attention to my temptation to rush.”

- “For the next case, my ethical focus will be speaking about the patient by name.”

You just closed one loop and primed the next.

Part 6 – Training This: From Concept to Habit

Reading a checklist is useless. You have to train it into your muscle memory like any procedural skill.

Here is a practical build‑out over 4–6 weeks.

Week 1–2: Pre‑Procedure Only

Pick one type of procedure you do regularly (e.g., peripheral nerve blocks, colonoscopies, LPs).

For every case in that category, do:

- 5‑question cognitive time‑in

- 3‑breath reset

Nothing else. No intra‑case loops yet. Just get used to dropping into the room with intention.

Week 3–4: Add the Situation Loop

Same procedure type, now plus:

- One 60‑second situation loop at mid‑case

- One ethical mid‑case question: “Would I be comfortable with this on video?”

Track on a scrap sheet or note app: number of times you caught yourself rushing, emotionally flooded, or tunneling. You want explicit data about your mind, not vague “I was mindful.”

Week 5–6: Add Post‑Procedure Debrief

Now you are doing:

- Pre‑procedure time‑in

- Mid‑case situation + ethical loop

- 1‑minute post‑case debrief

After a month or two, this pattern stops feeling artificial. It becomes the way you “set up” for procedures, like glove size and preferred gown.

Part 7 – The Ethical Spine: Why This Is Not Optional

There is a temptation to treat all mindfulness content as optional self‑care. That move is comfortable but wrong here.

During an invasive procedure, you hold:

- The power to injure or heal

- The power to treat a person as an object or as a subject

- The power to model for trainees what “normal” behavior in the procedure room looks like

A cognitive checklist is not about making you feel Zen. It is about:

- Nonmaleficence – Reducing harm caused by distracted, rushed, or ego‑driven action.

- Beneficence – Deliberately orienting toward what benefits this specific patient right now.

- Respect for autonomy – Even sedated patients deserve to be treated as if they were fully present. Your words and tone count.

- Justice – Not giving less care, less focus, or less respect to the “difficult,” the uninsured, the obese, the “frequent flyer.”

If you are serious about being an ethical operator, your inner climate is part of your procedural competency. Not an extra. Core.

I have heard attendings say, “I do not need that mindfulness stuff; my complication rate is fine.” That is like saying, “I do not need a pre‑flight checklist; I have not crashed yet.” It confuses luck with process.

Key Takeaways

- Procedural safety and ethics hinge as much on your mind state as on your technical skills. A cognitive checklist makes that visible and adjustable in real time.

- Embed simple, fast practices at three points: a 5‑question cognitive time‑in before the case, 5–10 second attention and ethical loops during, and a 1‑minute reflective debrief after.

- Treat this as part of your professional standard, not a wellness add‑on. How you show up mentally in the procedure room is as much a matter of ethics as whether you scrub properly.