It’s 4:30 p.m. You just finished a brutal ward block, and your phone buzzes with an email from your program director:

“Can you stop by my office tomorrow? I’d like to discuss your moonlighting hours.”

Your stomach drops. You’ve been picking up extra shifts—ED fast-track, a telemedicine gig, maybe some cross-coverage on nights—to keep up with loans and maybe afford something resembling a life. You’re not unsafe. Your evaluations are fine. But you already know where this is going: they think you’re moonlighting too much.

Here’s how to handle that situation like a professional—and protect both your training and your paycheck.

Step 1: Before the Meeting – Get Your Facts Straight

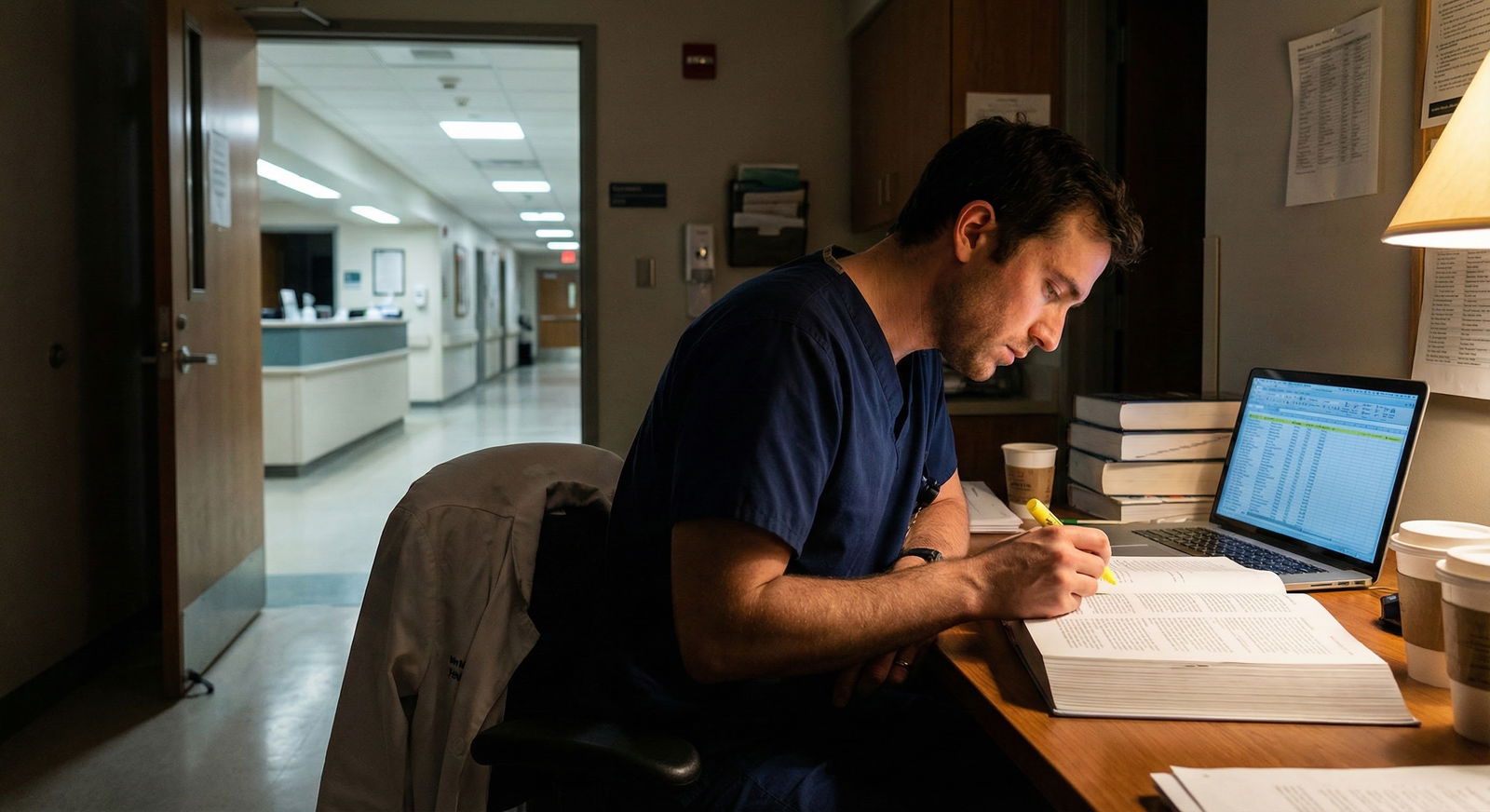

Do not walk into that office “hoping it’s fine.” You need data.

1. Pull your actual hours

You need three sets of numbers:

Duty hours with your home program

- Your last 3–6 months of logged hours (MedHub, New Innovations, whatever you use).

- Any weeks where you were close to or at 80 hours.

- Any flagged violations, even if they were “explained away.”

Moonlighting hours

- Dates, times, and location of all moonlighting shifts.

- Whether each shift was internal or external.

- Whether you were post-call or pre-call for any of them.

Combined total

- You want to know: are you actually breaking ACGME or just making them uncomfortable?

- ACGME cares about:

- ≤ 80 hours/week, averaged over 4 weeks

- 1 day in 7 free of clinical duty, averaged over 4 weeks

- 10 hours between shifts (and some flexibility rules, but do not expect them to fight for you on that)

If you’re already over 80 hours/week averaged—or you’ve had some obviously unsafe stretches (e.g., 28h call followed by a 10h moonlighting shift)—you need to know that before you open your mouth.

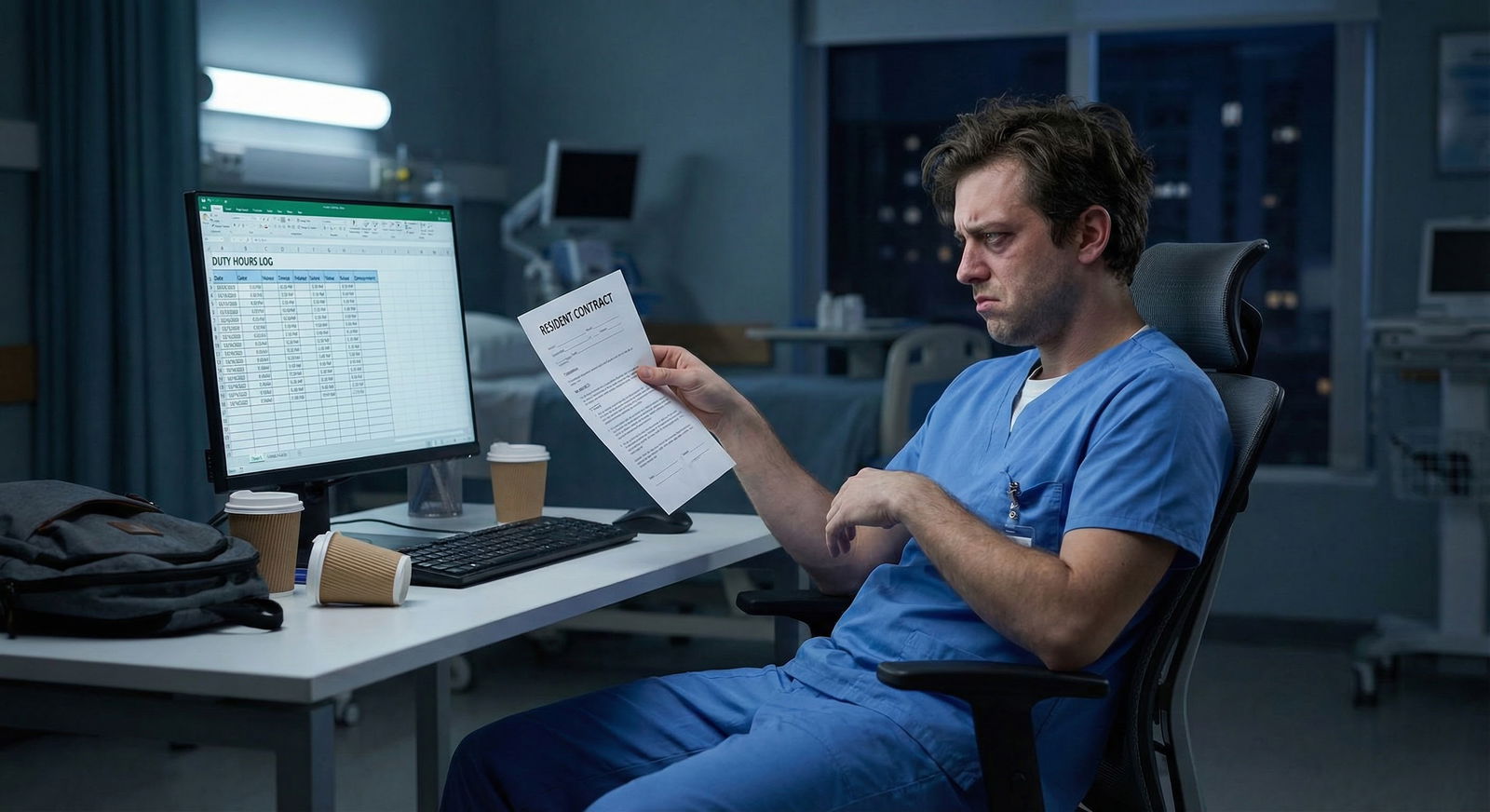

2. Re-read your contract and policies

Grab three documents:

- Your residency contract

- The program’s moonlighting policy (often in your handbook)

- The GME/institutional moonlighting policy

Look specifically for:

- Whether external moonlighting is allowed and under what conditions

- Whether internal moonlighting counts toward duty hours (it should)

- Whether there’s a written cap on moonlighting hours

- Whether PD pre-approval is required and how it’s documented

- Any language that says “may be revoked at PD’s discretion” (this is common)

You’re looking for: are you technically compliant or technically exposed?

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No limit stated | 25 |

| Max 12 hrs/wk | 35 |

| Max 24 hrs/wk | 20 |

| Internal only | 20 |

3. Check your performance reality

Harsh truth: if you’re average-to-good, you have leverage. If you’re already on their radar for anything, you don’t.

Look at:

- Recent evals (any comments about fatigue, delays, “availability,” or responsiveness?)

- Recent incidents (near-misses, patient complaints, late notes, missed conferences)

- Any emails about being late post-moonlighting or looking exhausted

If you can see the pattern they’re going to bring up, you’re not blindsided when they say it.

Step 2: In the Meeting – How to Talk So You Don’t Make It Worse

You walk in. Door closes. PD looks serious. This is where people either salvage the situation or get their moonlighting shut down completely.

1. Start by listening, not defending

When they start with, “We have concerns about your moonlighting,” don’t jump in with, “But I’m under 80 hours.”

Say something like:

“I appreciate you telling me that. Can you walk me through the specific concerns you’re seeing?”

Then actually shut up. Let them talk. PDs will often reveal exactly what they care about:

- “We’re worried about patient safety and fatigue.”

- “You’ve had multiple late arrivals on post-moonlighting days.”

- “Your notes and follow-up tasks are getting delayed.”

- “You’re setting a precedent the other residents are noticing.”

Once you know which problem they think they’re solving, you can respond intelligently.

2. Own what’s obviously true

If you’ve had any incidents tied to moonlighting—or honestly even adjacent—you don’t win by denying reality.

Examples of reasonable responses:

- “You’re right about the late post-call start time. That’s not acceptable and I’ve already stopped taking shifts that cut into my post-call day.”

- “I agree this past month’s schedule wasn’t sustainable. I bit off more than I should have.”

- “I can see how the near-miss on that cross-cover night looks. That scared me too, and I’ve adjusted my schedule since then.”

PDs are used to residents getting defensive. Contrition + concrete changes goes a long way.

3. Present your data calmly

If you’re actually within policy and safe, this is where you lay it out.

You might say:

“I took a look at my last 8 weeks of hours. Counting moonlighting, my average is 72 hours/week, and I’ve had at least 1 day off in 7 every week. I’ve brought a summary if it helps.”

Hand over a simple printout or 1-page summary. Not a manifesto.

| Week | Program Hours | Moonlighting Hours | Total Hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | 10 | 68 |

| 2 | 60 | 8 | 68 |

| 3 | 62 | 6 | 68 |

| 4 | 64 | 4 | 68 |

You’re not arguing. You’re showing you took their concern seriously enough to run the numbers.

If you found any close calls:

“I did see that week of wards plus two weekend shifts where I hit 79 hours. I agree that’s too close to the line, so I’ve stopped scheduling weekend moonlighting on those heavy rotations.”

You’re telling them: I’m not reckless; I self-correct.

Step 3: Address the Real Issue – Safety, Optics, or Control

Program directors rarely say the quiet part out loud, but it breaks down into three buckets: safety, optics, or pure control. How you respond depends which one you’re dealing with.

A. If their concern is safety/fatigue

This is the one concern that’s actually legitimate. Exhausted you is dangerous you.

What you do:

- Acknowledge the risk directly

“I agree that fatigue is a real risk, and I don’t want to put patients or myself in that situation. I’m willing to adjust my moonlighting to make sure I’m rested on high-acuity days.”

- Offer boundaries yourself

Examples:

- No moonlighting on:

- Pre-call days

- ICU weeks

- 24-hour call weekends

- Cap your own moonlighting hours:

- “I’ll limit myself to 1 shift/week and avoid stretches longer than 6 days in a row without a full day off.”

- Ask for collaborative structure

“Would it make sense to set some specific guardrails together? For example, limiting to X hours/month and no shifts on certain rotations?”

This frames you as someone trying to be responsible, not push limits.

B. If their concern is optics and politics

Sometimes you’re perfectly safe, but:

- Other residents are complaining, “Why do they get to moonlight so much?”

- Attendings have started saying, “I think they’re tired from all that moonlighting.”

- The hospital is nervous about liability or accreditation visits.

Here the problem isn’t what you’re doing—it’s who sees it.

How to respond:

- Lower the profile of your moonlighting

- Cut back on:

- Posting your moonlighting life on group chats or social media

- Talking about how much you’re making per shift

- Bragging about “working 100 hours this week”

- Show you understand the optics

“I get that even if I’m technically within the limits, it can create perceptions of fatigue or inequity. I’m willing to adjust my schedule and keep this lower profile to avoid sending the wrong message.”

- Request specific, not vague, expectations

“Can we define what you’d be comfortable with—like maximum X shifts/month or only on Y rotations—so I can stay firmly within those expectations?”

Now if they say “1 shift a month” on a chill rotation, you know what game you’re playing.

C. If the issue is pure control

Sometimes the PD just doesn’t like moonlighting. At all. They won’t say, “I don’t like residents making extra money,” so it comes out as vague phrases:

- “I just don’t think it’s appropriate at this stage in your training.”

- “You should be focusing more on reading and research.”

- “It sends the wrong message to faculty.”

If you’re in a program like this, you have very little leverage. They hold your graduation and board eligibility. You do not win a power struggle.

Here’s how to handle it without self-destructing:

- Clarify the rule in writing

“To make sure I’m clear, are you asking me to stop all moonlighting completely, or to limit it to certain situations?”

Then follow up with an email after the meeting:

“Thanks for meeting today. My understanding is that I’m not permitted to moonlight for the remainder of this academic year. If anything about that understanding is incorrect, please let me know.”

Now you’ve got documentation. That matters later if they decide to twist the story.

- Do not sneak around them

If you think, “I’ll just do unlogged telemedicine,” and they find out, you’re done. That’s the kind of thing that ends with “unprofessional behavior” in your file.

- Shift to damage control and long game

You may need to:

- Pause moonlighting temporarily

- Rebuild trust

- Revisit the conversation in 6–12 months with improved evaluations and no incidents

You’re playing for your board certification and fellowship letters, not one more $1,200 shift.

Step 4: If You Actually Have To Cut Back – How To Survive Financially

Let’s be honest: most people moonlight because the pay is trash and loans are huge. If the PD clamps down, you need a plan that isn’t “just suffer.”

1. Run a quick financial triage

Ask yourself:

- What exactly was the moonlighting money covering?

- Required expenses (rent, childcare, minimum loan payments)?

- Upgrades (nicer apartment, travel, big car payment)?

If you were using moonlighting to cover essentials, you have a real problem. If it was lifestyle inflation, you have more options.

Make a brutally honest list:

- Fixed essentials: rent, food, transport, childcare, minimum payments

- Negotiable extras: subscriptions, car upgrade, high-end gym, frequent takeout

Cut the obvious stuff first. Then see what’s left.

2. Talk to your loan servicer or financial aid office

You can sometimes:

- Adjust repayment plans (PAYE/REPAYE/SAVE, income-driven)

- Temporarily reduce payments

- Get interest-only or hardship accommodations

If you’re in PSLF territory, you definitely want payments as low as possible anyway. Moonlighting to pay down PSLF-eligible loans faster is usually a bad optimization.

3. Consider safer, PD-palatable alternatives

Some program directors are more comfortable with:

Internal moonlighting they control

- Extra in-house shifts on services they know

- Short backup coverage instead of full-blown ED shifts

Side work that isn’t clinical duty

- Paid teaching sessions (Step tutoring, school-run review sessions)

- Small research stipends or QI project support

Pitch it like:

“If external moonlighting is off the table, would you be open to limited internal extra shifts on lower acuity services, within duty hours, or paid teaching? I’m trying to close a financial gap without compromising my performance here.”

Some will still say no. Some will give you a controlled path.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Cut expenses | 30 |

| IDR loan changes | 25 |

| Limited internal shifts | 20 |

| Tutoring/teaching | 15 |

| Spouse/partner income | 10 |

Step 5: Protect Your Reputation and Paper Trail

Whether this goes smoothly or badly, you need to think about what’s in your file and how it looks to future employers and fellowship programs.

1. Follow up every critical conversation with email

Short, factual, no attitude. Something like:

“Thanks for meeting today to discuss my moonlighting.

As we discussed, I’ll [limit moonlighting to internal shifts only / stop all external moonlighting / cap to X hours per month and avoid certain rotations]. I’ll keep logging all hours accurately to remain compliant with duty hour policies.

Please let me know if you’d like me to make any additional changes.”

You’ve:

- Shown you took it seriously

- Documented the agreement

- Protected yourself from “they didn’t listen” narratives

2. Ask directly about impact on your standing

If you sense this is escalating:

“I want to make sure I understand the implications of today’s discussion. Is this going to affect my promotion, graduation, or my standing in the program?”

If they say “No, as long as you do X,” then do X. Perfectly.

If they hedge, you know you’re in deeper trouble and need to involve the GME office or a trusted faculty mentor early.

3. Fix the behavior first, repair the image second

Once you’ve agreed to changes, over-comply for a while:

- Be visibly awake, present, and prepared

- Be early instead of just on time for a bit

- Stay on top of notes and follow-ups

- Participate in conference, show you’re engaged

People talk. You want the whisper network to shift from “They’re always moonlighting and tired” to “They really turned things around.”

Step 6: Long-Term Strategy – Moonlighting Without Burning Your Career

If you’re going to keep moonlighting at all, you need rules that protect you from yourself and from the PD.

1. Build personal rules stricter than the ACGME rules

Examples that actually work in real life:

- Never moonlight the day before 24h call or ICU admit days

- Never string more than 6 days of clinical work in a row, including moonlighting

- Hard cap: total hours (program + moonlighting) ≤ 70–72/week on average

- No new moonlighting gigs during PGY-1, and be selective PGY-2

You’re not a machine. And yes, I’ve watched residents wreck themselves and then wonder why their fund of knowledge and performance plateaued.

2. Pick the right moonlighting type

Some moonlighting setups are safer and less politically toxic than others.

| Type | Fatigue Risk | PD Optics | Pay/hour |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED fast-track | High | Medium | High |

| Inpatient cross-cover | High | Medium | High |

| Telemedicine (low acuity) | Low | Variable | Medium |

| Internal clinic coverage | Medium | Better | Medium |

| Remote chart review | Low | Better | Low |

High-acuity, overnight-heavy gig + full residency schedule = red flags. If you can shift toward low-acuity, predictable, or remote work, you reduce both actual and perceived risk.

3. Consider the fellowship/employment angle

Fellowship PDs and hiring groups care more about:

- Your letters of recommendation

- Your clinical skill and judgment

- Your professionalism narrative

A note that you “disregarded program policies” around moonlighting will hurt you more than an extra $20k in residency ever helps.

So when you’re weighing, “Do I fight hard to keep that extra tele-ICU weekend?” the real question is: “Would I trade a lukewarm PD letter for this?”

Usually not.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | PD raises concern |

| Step 2 | Admit issue and cut back |

| Step 3 | Collaborate on limits |

| Step 4 | Document and comply |

| Step 5 | Adjust optics and schedule |

| Step 6 | Follow up by email |

| Step 7 | Within duty hour rules? |

| Step 8 | Safety/performance concerns? |

| Step 9 | Pure control issue? |

FAQs

1. Can my program actually forbid all moonlighting, even if ACGME allows it?

Yes. ACGME sets the ceiling, not the floor. Programs and institutions can be stricter than ACGME. If your contract or handbook says moonlighting is “at the discretion of the program director” or requires written approval, they absolutely can shut it down. You might not like it, but fighting that head-on usually backfires.

2. Should I ever bring up my financial situation as a reason to keep moonlighting?

You can mention it briefly, but do not lean on it as your main argument. Saying, “I’m trying to cover basic expenses and loans” is human and reasonable. Turning it into, “I need this or I can’t survive” puts the PD in a corner—they’re not going to risk patient safety or accreditation for your budget. Lead with safety, compliance, and performance. Sprinkle in financial reality, not the other way around.

3. What if my PD says my moonlighting is a “professionalism” issue?

You have to take that very seriously. “Professionalism” language is what shows up in your file, in CCC notes, and sometimes in letters. Ask for specific behaviors they’re labeling as unprofessional: missed conferences, excessive fatigue, complaining in front of others, not being transparent about shifts. Fix those aggressively, document your changes in a follow-up email, and consider looping in a trusted faculty mentor or the GME office if you think the label is unfair. But do not ignore it.

Key points to walk away with:

- Go into the conversation with numbers, policies, and a clear view of your own performance. Not vibes.

- Show you understand safety and optics, adjust your moonlighting boundaries yourself, and document every agreement in writing.

- Protect your reputation and long-term career; no single moonlighting gig is worth a permanent “professionalism” question mark in your record.