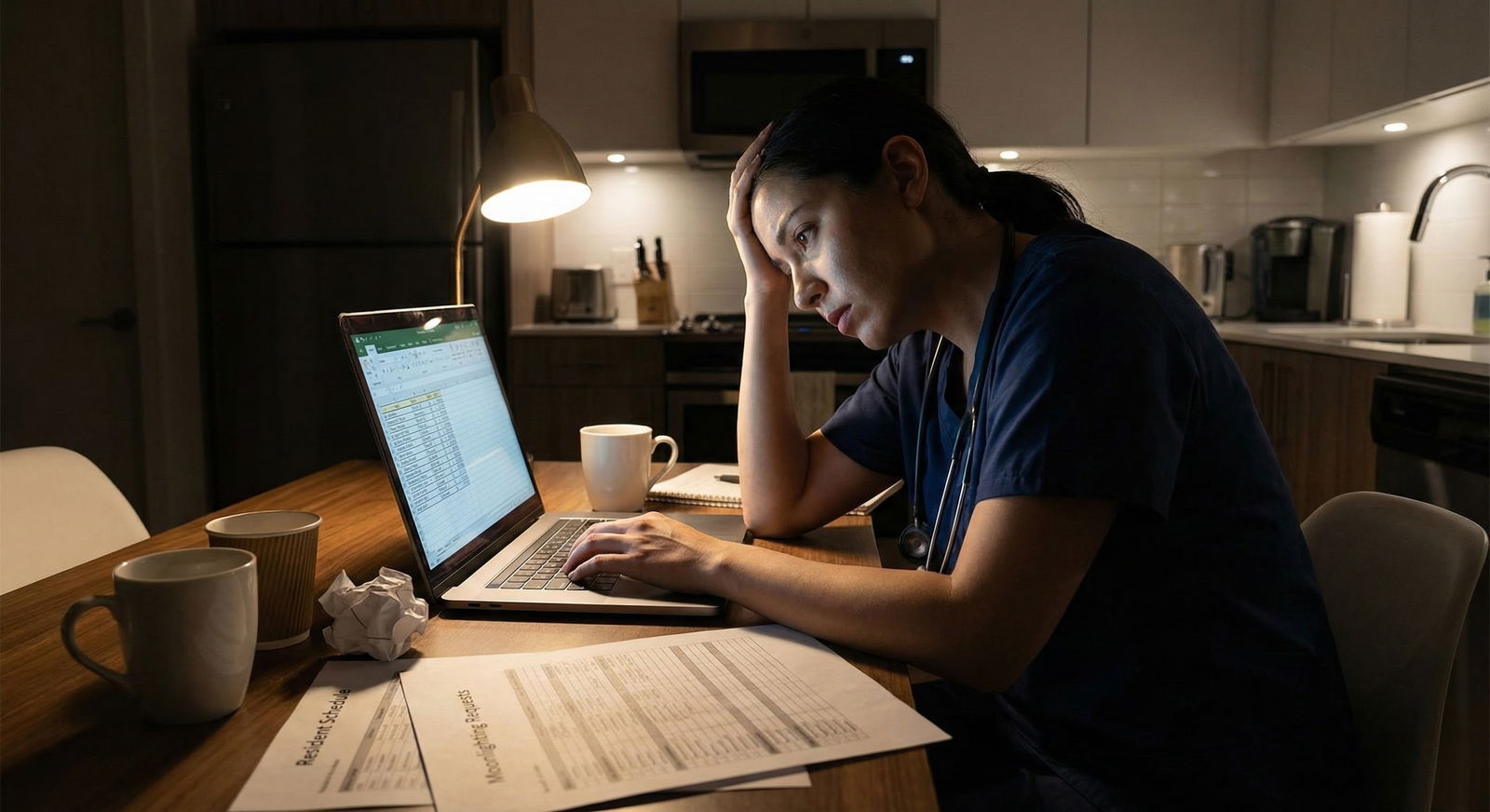

It’s 11:47 p.m. You’re in your call room or on your couch, half in scrubs, half in sweats, staring at your employment contract on the screen. The numbers are right there: salary, RVUs, non-compete, laughable CME money. And your chest drops because you’ve just realized… it’s bad. Low-ball bad. “Did I just screw up my entire financial future?” bad.

You’re replaying the signing moment in your head. You remember nodding on Zoom, thinking, “This seems fine, I just need a job.” No lawyer. No negotiation. HR telling you, “This is our standard contract; everyone signs it.” And you… did.

Now you’re looking at Reddit threads where people throw around starting numbers that are $50K–$150K higher than yours, talking about huge sign-on bonuses and RVU upside. And you feel sick.

So let’s talk about it. Directly. Because your brain is spinning worst‑case scenarios, and I live in that headspace too.

First: No, Your Financial Future Is Not Ruined

I’m not going to sugarcoat it: signing a low-ball contract isn’t ideal. It probably means you’re leaving money on the table. Sometimes a lot.

But “ruined”? No.

Here’s the unsexy truth: the biggest determinant of your long‑term financial life is not the first contract you sign. It’s:

- How long you let a bad deal drag on

- How fast you correct course

- How you manage your lifestyle while you fix it

You know what does ruin people? Signing one terrible contract, then signing another one just as bad because they’re too scared or exhausted to change anything. Plus buying the huge house, the luxury car, and locking themselves into that overhead.

You made one bad-ish (maybe very bad) decision under pressure, with limited data, in a rigged process that’s designed to exploit exactly that. That’s not a character flaw. That’s a system problem.

But here’s the catch: you cannot stay frozen in regret. Worry is only useful if it pushes you toward action.

What “Low‑Ball” Actually Means (And How Bad Yours Might Be)

Before spiraling, you need to know if your contract is:

- Mildly under market

- Clearly low‑ball

- Predatory

Right now, it probably all feels catastrophic. Let’s add some structure.

| Category | Mildly Under | Low-Ball | Predatory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Salary | 5–15% low | 15–30% low | >30% low |

| Bonus/RVU | Reasonable | Confusing | Nearly impossible |

| Non-compete | Short/small | Broad region | Huge region/time |

| Call Pay | Slightly low | Very low | None |

This is rough, obviously. But walk through it honestly.

If your base salary is maybe 10% below MGMA median for your specialty and region, with okay benefits, this is annoying, not life‑ending. If you’re 30–40% under, saddled with a massive non‑compete and no realistic bonus upside… that’s in “you need an exit plan” territory.

You know what most people do at this point? They say, “Well it’s done, I guess I just live with it.” And then five years go by.

Don’t do that.

The Four Concrete Levers You Still Have

Even after signing, you still have options. Not fantasy options. Real ones.

1. Renegotiate (Yes, Even Now)

People act like a signed contract is carved into stone and guarded by dragons. It’s not. It’s paper with signatures.

Can you tear it up tomorrow and write a new one? Probably not. But can you:

- Ask for a mid‑year review based on your performance?

- Request adjustment before a renewal term kicks in?

- Negotiate specific pieces (call pay, moonlighting permission, bonus structure) even if base salary “can’t” be touched?

Yes. I’ve watched this happen.

The script is not, “I need more money because I found out I’m underpaid.” Nobody cares. The script is:

- “Here’s what I’ve produced in RVUs/relative to peers.”

- “Here’s my panel growth / call coverage / additional responsibility.”

- “Here’s why an adjustment makes sense for retention and fairness.”

If your system cares about retention at all, they’ll at least hear you. Best case, you get a raise or improved terms. Worst case, they say no and you just learned something important: this is not a long‑term home.

2. Use Moonlighting and Side Gigs as a Pressure Valve

This is the “Moonlighting and Benefits” category, so let’s talk about the brutal-but-real fix: you can partially brute‑force your way out of a bad contract with extra income.

But. Only if your contract actually allows it.

If there’s an exclusivity clause or your employer has rules about outside work, you need to check those before you do anything. If you’re allowed, moonlighting can:

- Close the gap between your low salary and where you “should” be

- Accelerate loan payoff

- Build an escape fund so you’re not trapped when the renewal comes up

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No Moonlighting | 0 |

| $1K/month | 36000 |

| $3K/month | 108000 |

| $5K/month | 180000 |

That’s the difference over just three years. Do I think grinding extra shifts forever is sustainable? No. But as a tactical, short‑term move while you plan your exit or renegotiation? It can literally change your trajectory.

And if clinical moonlighting isn’t realistic, there are other “extra” levers: telemedicine shifts, chart review, urgent care, locums during vacations. None of this is glamorous. It is power.

3. Treat This Contract Like a Fellowship, Not a Life Sentence

Here’s the mental reframing that helps a lot of people breathe again:

You did a fellowship in “Bad Contract Medicine.”

Meaning: this is temporary, your goal is skill and experience acquisition, and you leave when it ends.

Most first contracts are 2–3 year terms. Instead of asking, “How do I survive this forever?” ask:

“What can I get out of this 2–3 year stretch that maximally improves my next contract?”

That might be:

- Procedural volume that makes you more marketable

- Leadership roles (clinic lead, quality projects) that justify higher pay later

- Specific niche skills (OB in FM, advanced endoscopy in GI, etc.)

This isn’t rationalizing exploitation. This is refusing to let a bad deal be just a bad deal. You’re harvesting every ounce of career capital from it, then you’re done.

4. Stop the Lifestyle Creep You Can’t Afford (Yet)

This is the one everyone hates.

A low‑ball contract + “I’m an attending now, I deserve this” lifestyle is the combo that will make you feel financially ruined. You already know this, but you’re probably still sitting with a Zillow tab open.

If you’re underpaid right now, I’d argue you have less room than the average new attending to do the big shiny things:

- Oversized house

- New luxury car

- Private school starting day one

- Massive renovations

You don’t have to live like a resident forever, but you do have to accept that your margin is thinner. Every big fixed payment you take on makes it harder to leave this job later. And you need the option to leave.

Your contract is bad. Don’t build your financial life on top of it as if it’s permanent.

Planning Your Exit Without Blowing Up Your Life

Okay, worst‑case brain time. Let’s assume:

- Your contract is truly low‑ball

- They won’t renegotiate

- You’re stuck for a term because of non‑compete or relocation issues

So you’re there. For now. What do you do?

You build a quiet, methodical exit plan.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Realize contract is low |

| Step 2 | Gather data on market pay |

| Step 3 | Review contract terms |

| Step 4 | Start networking now |

| Step 5 | Focus on skills and savings |

| Step 6 | Update CV and talk to recruiters |

| Step 7 | Apply for new roles 9-12 months before end |

| Step 8 | Use offers to negotiate or leave |

| Step 9 | When does term end |

A rough sequence:

You collect market data. MGMA if you can get it, but also job postings, recruiters, colleagues in your specialty in similar regions. Write the numbers down. You’re not imagining this.

You get your contract reviewed. Even after signing. Especially the non-compete and term/renewal section. A physician contract attorney can often find wiggle room you’d never see.

You set a timeline. If your initial term ends in 2 years, your “search seriously” window is 9–12 months before that. If non-compete limits geography, you start mapping out acceptable regions now.

You build a financial cushion. Every extra dollar (from moonlighting, from cutting expenses, from saying no to the 3rd vacation) goes to “exit money.” This is what lets you walk away if they play hardball.

You network quietly. Talk to alumni, old attendings, reps, hospitalists at the community hospital you admit to. Many good jobs never hit the big job boards. You want to be top of mind when someone says, “We might be hiring.”

This is not dramatic. No big email announcing your rage. Just calm, boring, methodical preparation for your next move.

But What About the Years I Already Lost? The “I’m Behind” Spiral

Let’s talk about that specific sick feeling: “I’m now 2–3 years behind everyone else financially. That’s compounding I’ll never get back.”

You’re not wrong about the math. If you made, say, $75K less per year than you “should” have for 3 years and didn’t make it up with moonlighting, that’s $225K not earned. If you want to run compound interest comparisons, you can absolutely torture yourself doing that.

But here’s the other piece that’s also true:

Most physicians don’t ramp to their “real” market value on day one. Lots of people:

- Take lower‑pay jobs for location

- Do extra training

- Start in academics with lower pay

- Switch specialties or roles later

Your career isn’t a straight line. It’s more like a step function. Long flat-ish stretches, then big jumps.

If this contract lights a fire under you to take your next negotiation seriously, to learn to say no, to treat your time as expensive, that mindset shift alone can recover way more than you “lost.”

The scary part is real. The permanence you’re imagining is not.

How Benefits and Non‑Salary Stuff Fit Into This

One more thing: sometimes the salary is low‑ball because they’ve dressed up the rest of the package and convinced you that “total comp” is great. Sometimes that’s true. Often it’s… marketing.

Look at:

- Retirement match: Are they actually putting in a solid percentage, or is it a 1–2% joke?

- Health insurance: Are your premiums and deductibles reasonable, or are you effectively paying thousands more a year than colleagues elsewhere?

- Disability and life insurance: Garbage or decent baseline?

- CME/education money: $1,000 and 3 days off vs $5,000 and 10 days off is a big difference.

- Call pay, shift differentials, holiday rates: This is where low salaries sometimes get “fixed,” but only if you actually see the dollars.

I’ve seen people panic about a $20K lower base, then realize their 401(k) match is 8% and their health insurance is heavily subsidized. That’s much less of a disaster.

I’ve also seen the opposite: shiny sign-on bonus, terrible ongoing benefits, call that’s basically free labor. That’s worse than it looks.

So if you haven’t fully dissected your benefits, do that. You might find it’s not quite as bad as your raw salary comparison suggests. Or you’ll confirm it is in fact bad, which at least justifies being aggressive with your next steps.

What You Can Actually Do This Week

You’re probably still thinking, “Okay, fine, but right now I just feel stuck and stupid.”

You’re not stupid. You were tired, desperate for a job, and trained in medicine, not in contract law or labor economics. You are, however, responsible for what you do next.

Very short list of things you can realistically do this week:

- Pull your contract out and reread the non‑compete, term, and renewal sections. Highlight them. This is your cage size and lock type.

- Email or call one physician contract lawyer and ask what they charge for a review of a signed contract and a 30–60 minute consult. You want strategy, not magic.

- Start a bare‑bones spreadsheet with three columns: “My comp,” “Market comp (low),” “Market comp (median)” for your specialty and region. Fill it in with anything you can find.

- Check your moonlighting/exclusivity clause. Are you allowed outside work with permission? No outside work at all? No competitive work? This matters.

None of these fixes everything. But they take you from vague dread to specific problems. Specific problems can be solved.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. I already signed. Is there any point in paying a lawyer now?

Yes. Not because they’ll magically void your contract, but because they can explain your non‑compete’s real teeth, your early‑termination risks, and where you might have leverage for adjustments or future negotiations. I’ve seen lawyers spot things like unenforceable non‑competes, missing consideration, or sloppy renewal language that gave physicians more room than they thought they had.

2. I feel guilty even thinking about leaving; they “took a chance” on me. Am I being ungrateful?

No. They hired you because you generate revenue. This isn’t charity. You can be professional, do good work, and still recognize you’re underpaid and plan a better situation. Guilt is exactly how institutions keep people locked into bad deals. You owe them competent care and reasonable notice. You don’t owe them your entire earning potential.

3. My contract bans outside work. Am I completely stuck on income?

You’re more limited, but not completely stuck. First, have a lawyer review that clause—some are narrower than they sound, or require “permission,” which you might be able to get. Second, if it’s truly airtight, your short‑term levers are internal: volunteering for paid call, extra shifts (if fairly compensated), leadership stipends, quality bonuses. And cutting expenses to boost savings while you plan your exit.

4. Won’t having a short first job on my CV make me look bad for future employers?

A one‑year job with clear, non-dramatic reasons (“misaligned expectations about compensation and schedule,” “family relocation,” “practice style mismatch”) is not some huge scarlet letter. Physician turnover is high; hiring committees know this. Chronic job‑hopping every year looks worse than one early miss that you then stabilize after finding a better fit.

5. How do I make sure I don’t get low‑balled again on my next contract?

You go in armed. Market data, other offers, a clear minimum number in your head, and a willingness to walk. You get the contract reviewed before signing. You refuse “standard contract, no changes” as the final word. You ask specifically about RVU rates, wRVU targets, call expectations, and non‑compete radius. And if their reaction to basic questions is defensive or dismissive, you treat that as the red flag it is.

Open your contract PDF right now. Scroll to the “Term and Termination” and “Restrictive Covenants” sections and highlight them. That’s your starting point. Not the anxiety spiral in your head—the actual words on the page.