What are you really risking if you match into a brand-new residency program… and two years in, leadership implodes or the ACGME steps in?

Let me be direct: some new programs are fantastic and launch great careers. Others are chaos with a logo. Your job is to tell the difference before you commit three to seven years of your life.

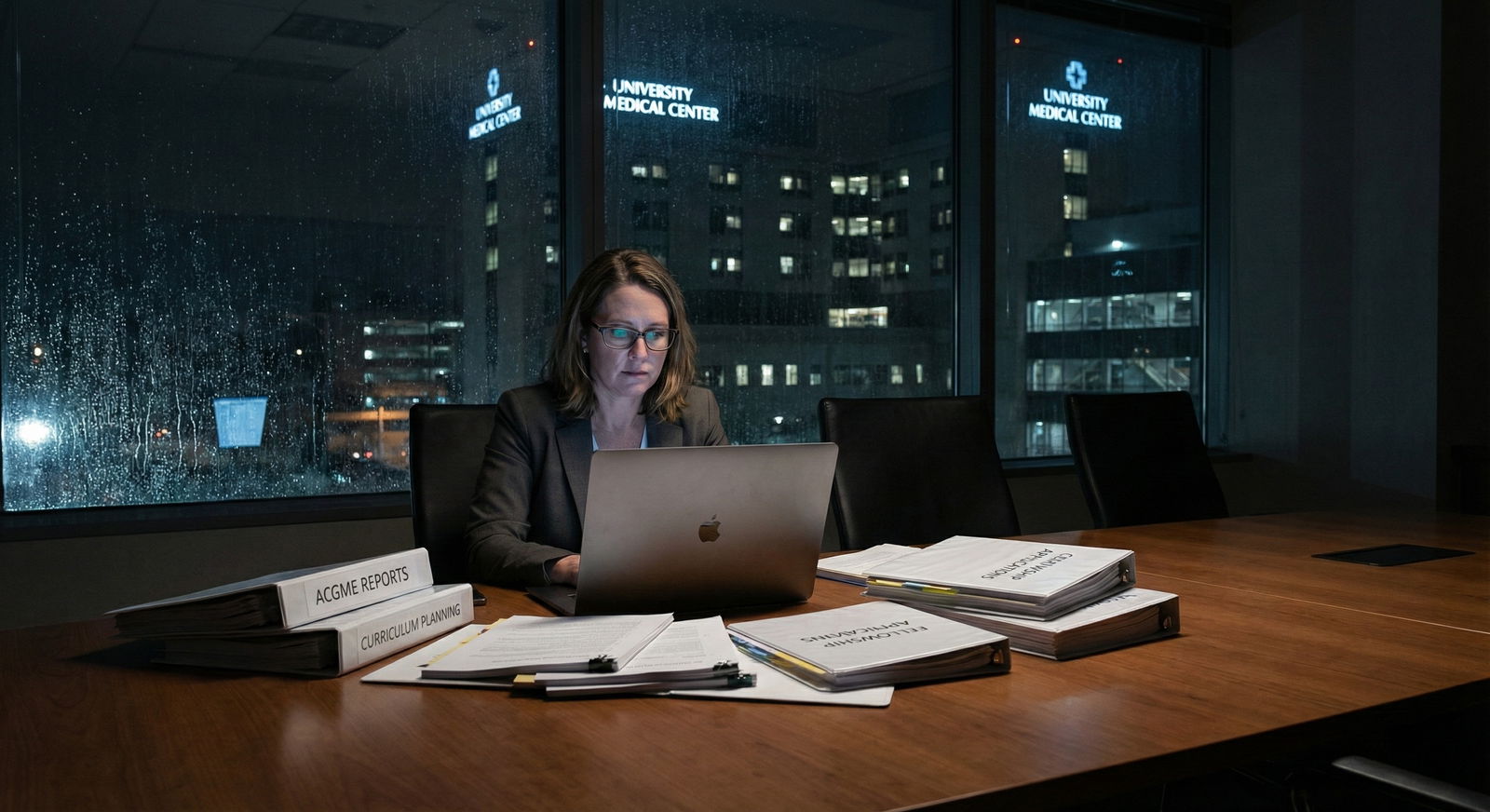

Here’s how you actually evaluate long-term stability instead of just trusting the glossy brochure and the PD’s pep talk.

Step 1: Separate “New” From “Unstable”

Not all “new” is bad. There’s a big difference between:

- A new program at a large, long-established academic medical center that already trains other residents and fellows

vs - A completely new teaching hospital with no graduate medical education (GME) infrastructure, starting multiple residencies at once.

If a place is already running multiple accredited programs successfully, adding one more is usually lower risk. If they’re building everything from scratch, the odds of growing pains (sometimes serious ones) go way up.

Use this mental model:

| Type of New Program | Relative Risk | Why |

|---|---|---|

| New program at major academic center | Lower | Existing GME support, stable leadership |

| New program at community hospital with other residencies | Moderate | Some GME experience, but resources may be tight |

| First-ever residency at a community hospital | Higher | No GME culture, systems built from zero |

| Brand-new hospital + brand-new program | Highest | Institutional instability plus GME inexperience |

If your program fits into that last category, you need to scrutinize everything more closely.

Step 2: Follow the Accreditation Trail (Not Just “We’re Accredited”)

Programs love to say “We’re accredited by ACGME.” That statement is almost meaningless without context.

You want to know:

- What type of accreditation?

- Any adverse actions?

- How long is the accreditation cycle?

Check this directly on ACGME’s public site, not just what the PD tells you.

What to look for

Accreditation status language

- “Initial Accreditation” – standard for new programs. Not bad, but it means they’re still proving themselves.

- “Continued Accreditation” – they’ve passed at least one major review. More reassuring long-term.

- “Probationary” or “Warning” – giant red flags.

Cycle length

Longer cycles (e.g., 5–10 years) generally mean more confidence from ACGME. Very short cycles or frequent reviews can suggest concerns.History of adverse actions

If the sponsoring institution has had probations or significant citations in other programs, assume risk extends to you.

Step 3: Look Hard at the Institution, Not Just the Program

Residents forget this: your “residency program” is just one small piece of a much larger machine. If the hospital or health system is unstable, your program is vulnerable by default.

Here’s what I check every time:

1. Financial health

If the hospital system is bleeding money, residency funding is not sacred. Look for:

- Recent news of closures, layoffs, or service line shutdowns

- Major mergers or acquisitions in the last 1–2 years

- Publicly reported financial losses

If the organization is publicly traded or part of a big system, you can often find financial reports or news articles. If every headline is “X Health posts record losses,” think twice.

2. Service lines and patient volume

No volume = no education. You need a hospital that actually sees your specialty’s bread-and-butter pathologies.

Ask for hard numbers:

- Annual ED visits

- Annual admissions / surgical case volume

- For specialties: number of deliveries (OB), cath lab volume (cards), endoscopy numbers (GI), etc.

If they dodge numbers and say, “We’re growing” or “We expect volume to increase,” that’s not stable yet. That’s hope.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| OB Deliveries | 1500 |

| General Surgery Cases | 1000 |

| ED Visits (k) | 60 |

| ICU Admissions | 800 |

These numbers are just example thresholds, not universal rules—but if the program is far below typical volumes for your specialty, it’s a problem.

3. Existing GME structure

Ask:

- How many other ACGME-accredited programs are running?

- Is there a dedicated GME office with staff (DIO, GME coordinator, etc.)?

- Are there institutional GME committees and resident councils already functioning?

No GME infrastructure = you’re the beta test. Some people are fine with that. You just need to know that’s what you’re signing up for.

Step 4: Study the Leadership Like Your Career Depends on It (Because It Does)

A brand-new program lives or dies on its leadership.

Program Director (PD)

You want a PD who is:

- Experienced in education – has been core faculty, APD, clerkship director, or PD elsewhere

- Stable geographically – not someone who jumps institutions every 1–2 years

- Clinically present – actually working in the hospital where you’ll train, not mostly remote

Ask blunt questions:

- “Is this your first time as PD?”

- “What prior roles did you have in GME?”

- “How long do you see yourself in this role?”

If the PD is brand new to GME, new to the hospital, and vague about their time horizon, your stability risk is high.

Faculty depth

If the program has 20 residents over time and 4 faculty total, that’s thin. That usually translates to:

- Faculty burnout

- Poor supervision

- Limited mentorship diversity

You want a decent ratio of core faculty to projected resident complement and at least a few established, respected clinicians in each key area.

Step 5: Talk to the People Already There (But Listen Between the Lines)

If they already have interns or the first couple of classes, those residents are your best data source. The problem? On interview day, many will be guarded. They know PDs can retaliate.

So you listen for what they don’t say.

Good signs:

- They can list specific strengths without hesitation

- They mention leadership responsiveness with concrete examples (“We asked for X and within 2 months they did Y”)

- They talk about their education, not just service work

- Long pauses when you ask about weaknesses, then vague answers

- Comments like “We’re still working out some kinks” with zero specifics

- Jokes about being “cheap labor,” “the scut monkeys,” or “pager mules”

If there are no residents yet, ask to talk to:

- Medical students who rotated there

- Residents from other programs at the same institution

- Nurses and staff (“How is it working with the new team?”)

You learn a lot from eye rolls and sighs.

Step 6: Examine Rotations and Partnerships Like a Contract

New programs often outsource key rotations until they build local capacity. That’s fine—if it’s formal, stable, and well-run.

Look for:

- Written affiliation agreements with other hospitals/clinics

- Clear details: who supervises you, where you chart, who evaluates you

- Long-term plans: which rotations are permanent vs temporary stop-gaps

Ask specifically:

- “Are any of our core rotations still pending approval?”

- “Have any outside sites ever dropped trainees?”

- “What would happen to my training if X site ended the affiliation?”

If they dodge or hand-wave this, that’s a stability problem.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Newly Accredited Program |

| Step 2 | Lower baseline risk |

| Step 3 | Higher baseline risk |

| Step 4 | Check volume and rotations |

| Step 5 | High risk - proceed cautiously |

| Step 6 | Reasonable stability |

| Step 7 | Moderate risk |

| Step 8 | Existing GME at institution |

| Step 9 | Stable PD and faculty? |

| Step 10 | Positive resident feedback? |

Step 7: Ask the Questions That Predict Long-Term Stability

Here are the questions I’d ask in any interview or second look, especially for new programs. Don’t ask all at once like a deposition; sprinkle them across conversations.

About institutional commitment:

- “How is the program funded, and is that funding locked in long-term?”

- “How does GME factor into the hospital’s 5-year strategic plan?”

- “What would need to happen for the institution to cut back on residency positions?”

About growth and caps:

- “What is your planned resident complement over the next 5–7 years?”

- “Are there caps from Medicare GME funding that affect expansion?”

- “Have you ever considered reducing positions or changing complement?”

About quality and oversight:

- “What metrics are you tracking to ensure residents are not just service coverage?”

- “How is resident feedback actually acted on? Can you give a recent example?”

- “How often does the GMEC review this program?”

You’re listening not just for the content but for whether they have specifics. Leaders who are actually running a thoughtful, stable program can answer these without dancing.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Institutional strength | 25 |

| Leadership quality | 25 |

| Clinical volume | 20 |

| GME infrastructure | 15 |

| Resident experience | 15 |

The exact percentages don’t matter. The point is: don’t obsess over just one area. A strong PD cannot compensate for a dying hospital, and a rich hospital cannot compensate for terrible volume.

Step 8: Check for Early Warning Smoke

Even if the building isn’t on fire yet, smoke matters. Here are early warning signs that future instability is likely:

- Rapid leadership turnover in the last 2–3 years (PDs, chairs, CMO, CEO)

- Frequent changes to the rotation schedule mid-year without clear educational reasons

- Residents from other programs quietly warning you to “be careful” or saying “we’ll see if it lasts”

- ACGME citations in other programs at the same institution for duty hour violations, supervision issues, or hostile culture

- Heavy reliance on locums or temporary physicians in key services

If you see multiple of these, understand you’re gambling. Some people will still take that bet, often for geographic or personal reasons. Just don’t pretend it’s not a bet.

Step 9: Weigh the Tradeoffs Honestly

There are upsides to new programs:

- You can help shape the culture and policies from the ground up

- You may get more leadership opportunities (chief, committees, curriculum design)

- In some less competitive fields or locations, you might match where older programs shut you out

- Faculty sometimes bend over backwards early on to make it work

But trade that against realistic risks:

- Unclear board pass track record

- Fellowship directors not knowing the program yet

- More administrative chaos

- Real possibility of ACGME scrutiny or probation during your time

What I’ve seen work well: applicants choose a newer program if either:

- It’s attached to a strong, established institution with multiple other solid residencies and clear volume

- They have a strong personal/geographic reason, and they go in clear-eyed about the risk profile

What doesn’t work: picking the shakiest new program just because it was the only place that ranked you highly, and telling yourself “it’ll probably be fine” without doing the homework.

Step 10: Your Quick-Check Framework

If you want a simple framework, run the program through this 5-point filter and be brutally honest:

- Institution – Financially stable? Not closing service lines? Real patient volume?

- GME Environment – Other successful programs? Solid DIO and GME office?

- Leadership – PD and chair experienced, stable, not obviously using this as a stepping stone?

- Training Quality – Case volume, procedure logs (if available), clear didactic plan, stable rotations?

- Resident Signals – Current residents (or students/nurses) describe the program with specifics and don’t look terrified?

If you can confidently check 4–5 of these boxes, the program is probably reasonably stable. If you’re at 2 or fewer, you’re making a high-risk choice. That doesn’t mean “never,” but it does mean “don’t be surprised if things blow up.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Institution | 8 |

| GME Environment | 7 |

| Leadership | 6 |

| Training Quality | 7 |

| Resident Signals | 5 |

You can literally score each area 1–10 for each program you’re ranking. Compare them side by side. Do not rely on vibe alone.

Here’s your next step: pick one new program you’re seriously considering and pull up the ACGME listing for both the program and its sponsoring institution. Write down: accreditation status, other programs at that institution, and any red flags you spot. If you can’t find convincing evidence of stability on paper, don’t assume it exists in real life.