The belief that you need a big-name academic lab to be competitive for residency research is flat-out wrong.

If you’re at a community med school with no major labs, no R01 factories, no HHMI stars wandering the halls—that’s not a death sentence for your application. It just means you need to stop chasing the traditional pipeline and start using the system you actually have.

I’ve watched students from tiny community programs match into derm, ortho, rad onc, academic IM. They did not magically conjure an NIH lab. They worked the angles that were actually available: QI, chart reviews, multi-center collaborations, and shamelessly leveraging clinicians who didn’t think of themselves as “researchers.”

Here’s how you do the same—step by step—without wasting the next two years waiting for a unicorn basic science mentor who isn’t coming.

1. Get Clear on What PDs Actually Care About

Program directors care a lot less about where you did research and a lot more about what it shows about you.

They’re looking for evidence that you can:

- Ask a focused question

- Follow through on a project

- Work on a team and hit deadlines

- Produce something: abstract, poster, manuscript, QI report

If you’re aiming for a competitive specialty (derm, plastics, rad onc, ENT, uro, ortho), research is almost mandatory. For things like IM, peds, FM, psych, EM, it’s helpful but not always required. Still, strong research can offset a lot—average Step scores, mid-tier school, few honors.

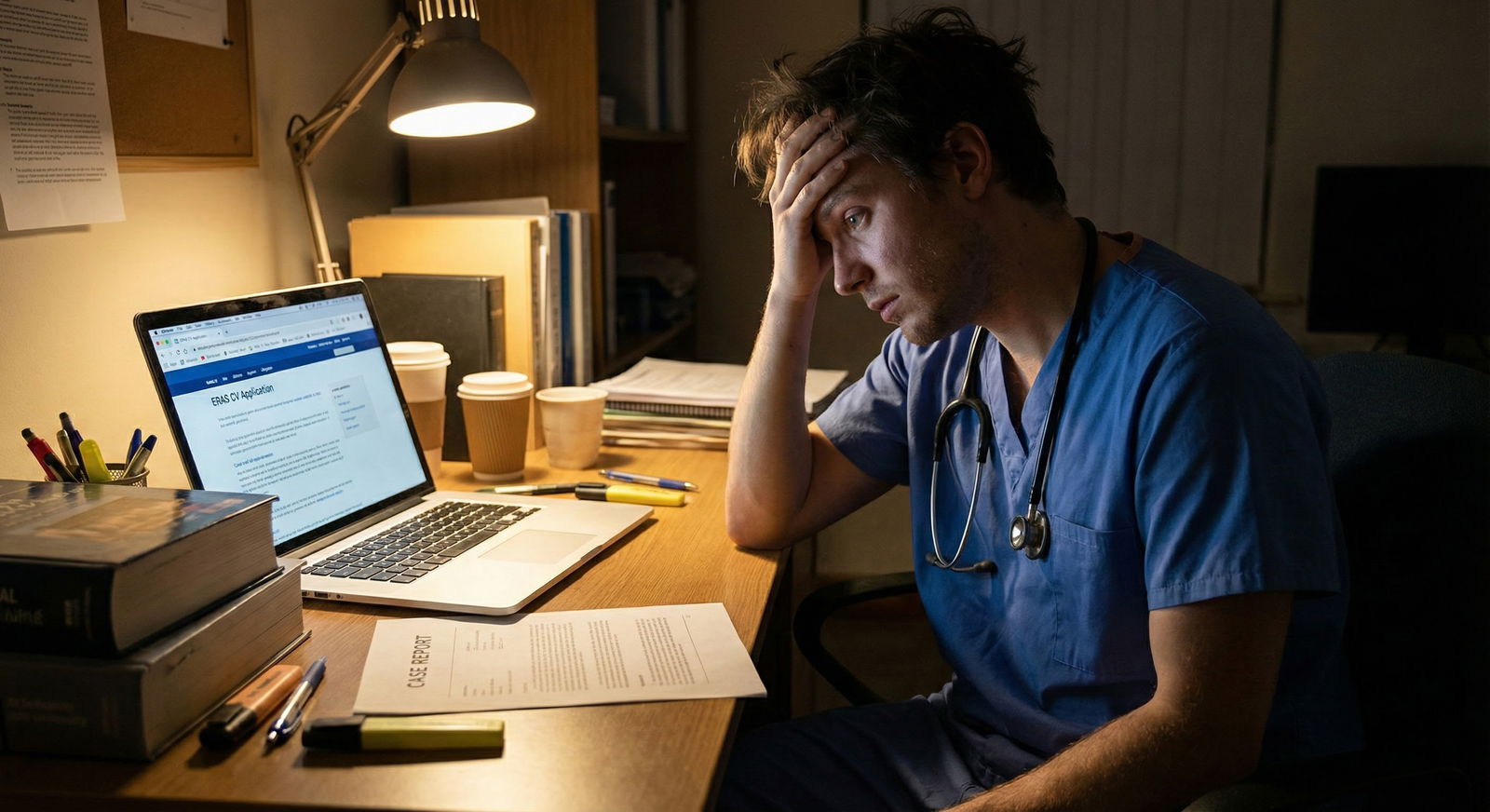

So your goal is not “I need a bench lab.” Your goal is: “I need 2–5 serious, finished projects by ERAS time, ideally with my name high on the author list.”

That is absolutely doable from a community school.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Minimal | 1 |

| Moderate | 3 |

| Strong | 6 |

Think in outputs:

- Minimum to look engaged: 1–2 things (poster or small paper)

- Solid for most fields: 3–5 things (mix of abstracts, posters, maybe 1–2 papers)

- Competitive-specialty range: 5–15+ things, but half can be small case reports, conference abstracts, etc.

You’re not trying to win a Nobel Prize. You’re trying to prove you’re productive and can ship.

2. Mine Your Community Hospital for Hidden Projects

Your hospital looks non-academic. It is not non-academic. It’s just disorganized academically.

There are projects hiding in:

- Quality Improvement (QI)

- Morbidity & Mortality (M&M) conferences

- EMR data you can pull for chart reviews

- Residents’ half-finished ideas

- Institutional requirements (sepsis bundle compliance, readmission rates, CLABSI reduction, etc.)

How to Start: The 1-Month “I Need a Project Now” Plan

Week 1: Information gathering

Walk up (yes, physically walk) to:

- Your clerkship director

- Chief residents in IM, surgery, EM

- The hospital’s QI or patient safety officer

- The person who runs M&M conferences

Say something like:

“I’m a [MS2/MS3/MS4] very interested in doing publishable work, especially in [insert specialty or topic]. Are there any ongoing QI, chart review, or clinical projects that need a student to help push them forward?”

Not “Do you have research?” That’s too vague. Ask about:

- “Projects that stalled and need someone to finish them”

- “Things that could turn into a poster or abstract quickly”

Someone will say, “Well, we do have this thing we’ve been tracking in Excel…” That’s your door.

Week 2–4: Anchor one project

Stake your flag in one realistic project:

- Retrospective chart review (e.g., outcomes of HF patients, readmission, ED revisits, antibiotic stewardship)

- QI project with measurable outcomes (hand hygiene compliance, time-to-antibiotics in sepsis, VTE prophylaxis rates)

- Case series (several cases of the same condition, managed similarly)

Your pitch:

“If I help with data collection and write-up, can I be first author or co-first?”

Get that clear early. You are not a free scribe; you are academic labor.

3. Lean Hard into QI and Clinical Outcomes

Community hospitals are QI factories and they do not realize it.

You don’t have a mouse room. You do have:

- Readmissions

- ED bounce-backs

- Sepsis alerts

- Heart failure pathways

- Anticoagulation protocols

- Hospitalist groups tracking metrics for payors

Why QI is Gold for Community Students

- It’s directly relevant to residency. PDs like seeing QI on your CV.

- You can do it with limited resources. EMR + Excel + IRB or QI approval.

- It’s fast. You can go from idea to poster in 6–9 months, sometimes faster.

Concrete Examples

- “Reducing 30-day readmissions for COPD at a community hospital using a discharge checklist.”

- “Improving time-to-antibiotics in septic shock through an ED protocol change.”

- “Impact of a standardized insulin sliding scale order set on hypoglycemia events.”

Structure it like:

- Pre-intervention data (retrospective)

- Intervention (protocol, checklist, education)

- Post-intervention data

Submit to:

- Hospital/system QI day

- Regional chapter meetings (ACP, SGIM, ACEP, ATS, etc.)

- Then write a short manuscript for a QI-friendly journal.

4. Turn Rotations into Research Fuel

Every rotation can be a research generator if you stop just trying to “do well on evals” and start collecting ideas.

During Core Rotations

On each service, ask:

- “What outcomes do you wish you had better data on here?”

- “What patterns do we see a lot that nobody has written up?”

- “What slides or topics do you keep reusing in teaching that could be formalized into a paper or poster?”

Examples:

- IM: recurrent C diff, HF admissions, diabetic readmissions

- Surgery: post-op infection rates, same-day discharge feasibility

- EM: frequent flyers, imaging overuse, sepsis response time

You are not just a learner; you’re a data harvester.

Case Reports (Fastest Win You’re Ignoring)

Whenever something weird walks in:

- A rare complication

- A drug reaction

- An unusual combination of conditions

- A dramatic radiology finding

Ask the attending: “Has anyone written this up? Would you be open to doing a case report together? I can do the heavy lifting.”

You’ll need:

- Detailed clinical course

- Imaging/pathology (de-identified)

- A short literature review

Target smaller or specialty case journals. They exist specifically for this.

5. Collaborate Beyond Your Campus Without Moving

You might not have big labs. But someone within 200 miles does. And they don’t care that much where you’re physically standing if you’re useful.

Step 1: Identify Nearby Academic Centers

Look for:

- State university medical center

- Large tertiary-care hospitals in your region

- VA hospitals with academic affiliations

Study their department websites for your specialty:

- Click faculty profiles

- Look for “main interests” and recent publications

- Identify 5–10 people whose work looks remotely interesting

Step 2: Cold Email Like a Professional, Not a Spam Bot

Your email should look like:

Subject: Medical student interested in [X] research – can help with [data analysis/literature review/chart review]

Dear Dr. [Last Name],

I’m a [MS2/MS3] at [Your School], very interested in [specialty/field]. I’ve been looking for opportunities to contribute to clinical or outcomes research, especially in [their topic].

I’ve had experience with [basic stats, Excel, R, RedCap, lit reviews—whatever is true], and I’m willing to help with chart review, data cleaning, or manuscript prep. I’m happy to work remotely and adapt to the needs of ongoing projects.

If you have a few minutes, I’d love to talk about whether there are any projects where an extra pair of hands would be helpful.

Sincerely,

[Name, Med School, Contact]

Do not ask for some huge independent project. Offer to be the grunt who moves existing work forward. That’s how you get in.

Step 3: Use Visiting Rotations as Leverage

If you do a sub-I or away rotation at a bigger center:

- Tell residents and attendings on Day 2: “I’m actively looking to work on a paper or abstract while I’m here. Anything low-hanging I can jump into?”

- Attend research meetings or journal clubs and linger afterward.

- Get on something—even a small project—before you leave.

Then keep working remotely after the rotation.

6. Play to the Timeline: When to Start, What to Prioritize

You don’t have unlimited time. Especially if you’re already in clinical years.

Here’s a rough, realistic framework.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| MS2 - Early MS2 | Learn basic stats & literature search |

| MS2 - Late MS2 | Join 1 QI or chart review project |

| MS3 - Early MS3 | Collect data, draft abstract |

| MS3 - Mid MS3 | Submit to regional conference, start second project |

| MS3 - Late MS3 | Turn first project into manuscript, add case report |

| MS4 - Early MS4 | Finalize manuscripts, update CV for ERAS |

| MS4 - Application Season | Present posters, discuss projects in interviews |

If You’re MS1/MS2

You have time. Priorities:

- Learn the mechanics: IRB basics, RedCap, basic biostats, reference managers.

- Attach yourself to 1–2 ongoing projects with clear mentors.

- Aim to have at least an abstract or poster by early MS3.

If You’re MS3 Just Starting

You do not have time to be picky or idealistic.

Focus on:

- Fast projects: retrospective chart reviews, QI, case reports.

- Joining projects close to submission, not just starting brand-new ones.

- Getting your name on something that will be presentable before ERAS.

If You’re MS4 Pre-ERAS and Research-Light

You’re in damage-control / triage mode:

- Case reports from your sub-I or away rotations.

- Short clinical vignettes for regional or national meetings.

- Realistic framing in your personal statement and interviews: emphasize what you started, what you learned, how you’ll continue as a resident.

7. Make Your CV Look “Academic” Even Without Big Names

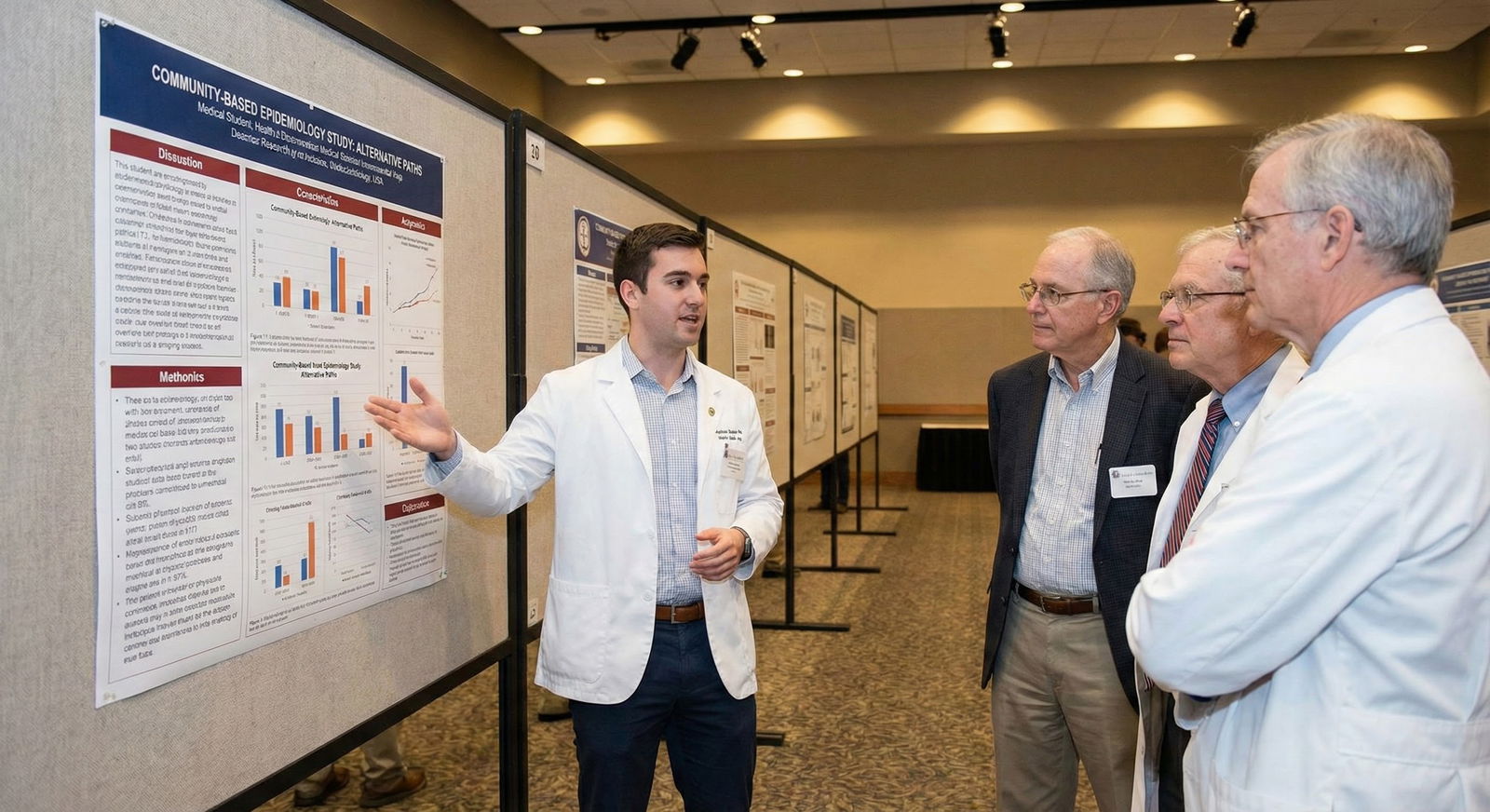

You can present community-based work in a way that looks intentional and cohesive.

Group your work around themes:

- “Quality improvement in inpatient medicine”

- “Emergency department operations and outcomes”

- “Diabetes management and readmission reduction”

On your CV, in ERAS:

- List QI projects under “Publications/Presentations” if they were actual posters or talks.

- Include “Institutional QI Day” or “Hospital Research Symposium” if that’s where you presented. It still counts.

- Don’t bury case reports. They’re real publications.

| Project Type | Difficulty | Time to Product | Looks Good For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case Report | Low | 1–3 months | All specialties |

| QI Project | Medium | 6–12 months | IM, EM, Surgery, FM |

| Chart Review | Medium | 6–18 months | Most specialties |

| Multi-center Collab | High | 12–24 months | Competitive specialties |

If you want an “academic vibe,” add:

- Teaching-related projects (curriculum development, OSCE design, simulation sessions you helped evaluate)

- Posters at specialty meetings, even if small (state chapters count)

8. The Politically Messy Stuff Nobody Tells You

You’re at a structural disadvantage. Pretending otherwise is naive. So you compensate by being smarter about three things: expectations, credit, and narrative.

1. Expectations: You Are Not Competing with MD/PhDs on PubMed Count Alone

A derm applicant from a top-10 school with 25 pubs and multiple first-authors in JAMA Derm is not your direct benchmark if you’re coming from a small community program. PDs know the pipeline is different.

Your bar is:

- Did you maximize what was available?

- Did you show sustained engagement?

- Did you finish what you started?

One well-done QI + a couple of case reports + 1–2 posters can beat five half-baked “in progress” projects with no outputs.

2. Authorship: Protect Your Position Up Front

Community settings can be loose with authorship. People add names like candy. You’re the one doing the midnight chart abstractions; you deserve visible credit.

Before you commit heavy time:

- Ask, “If I collect the data and draft the manuscript, would I be first author?”

- If they hedge or say “we’ll see,” that’s a red flag. Consider walking.

You’re allowed to insist on clear expectations. Politely. Early.

3. Narrative: How You Talk About This in Interviews

Own your context. Say things like:

- “We don’t have large basic science labs, so I focused on QI and outcomes that directly affected our patient population.”

- “Being at a community hospital pushed me to identify problems on the wards and turn them into projects we could actually implement.”

- “I had to build my own research infrastructure—finding mentors, learning IRB processes, setting up data systems—which I think will help me hit the ground running in residency.”

That sounds proactive, not apologetic.

9. Concrete Action Plan: Next 30, 90, and 180 Days

If you’re serious, this is what your calendar should actually look like.

Next 30 Days

- Identify 2–3 potential mentors at your own hospital (attendings, chiefs, QI officer).

- Have at least 3 face-to-face conversations asking explicitly about QI, chart review, or case report opportunities.

- Pick ONE project and get on the IRB or QI approval path if needed.

- Read 5–10 papers similar to what you’re trying to do (for structure).

Next 90 Days

- Finish data collection for at least one project.

- Draft an abstract and submit to:

- A regional specialty meeting (ACP, AAFP, ACEP, ATS, etc.)

- Or your hospital/system research/QI day

- Start a secondary, faster project (case report, smaller QI).

Next 180 Days

- Turn that first project into a manuscript and submit it somewhere, even if it’s a modest journal. Under review still counts.

- Present at least one poster or oral talk (local, regional, or national).

- Aim to have 2–4 items on your CV by ERAS: a mix of submitted/accepted abstracts, case reports, or manuscripts.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. I’m at a DO/community school with zero culture of research. Is it even worth trying?

Yes. You’re not going to build a translational science empire, but you can build a credible, activity-rich CV. Start with QI and case reports—those are feasible anywhere with patients and an EMR. Get 2–5 real outputs: posters, abstracts, short papers. That alone separates you from a huge chunk of your peers who did nothing.

2. I hate statistics and have no idea how to analyze data. What do I do?

You do not need to become a biostatistician. Partner with someone who has minimal stats comfort—another student, a resident, sometimes the hospital’s QI office. Learn just enough to understand: basic descriptive stats, p-values, confidence intervals, simple regression. There are free online courses and YouTube playlists that can get you there in a few weekends. For more complex work, co-author with someone who knows what they’re doing and focus your energy on data collection and writing.

3. How many publications do I actually need for a competitive specialty from a community school?

For very competitive specialties, more is better, but quality and first-authorship matter. From a community program, 5–10 items (including case reports, posters, and smaller journals) with 2–4 as first author is solid. If that’s not realistic, maximize what you can do: strong letters, high Step/COMLEX scores, honors on rotations, and a narrative that shows you squeezed everything possible out of your setting.

4. My only projects are small QI and case reports. Will top programs take that seriously?

If they’re well executed and you can speak intelligently about them, yes. Top programs care most about how you think and whether you finish what you start. In interviews, focus on your role in project design, implementation, and interpretation, not just “we found p<0.05.” Many faculty are frankly more interested in practical, implementable work than another basic science mouse study. You don’t apologize for doing community-relevant research—you lean into it.

Key points to walk away with:

- You do not need a big lab to build a legitimate research profile; QI, chart reviews, and case reports are your bread and butter.

- Stop waiting for the perfect mentor—go to the clinicians and QI people already frustrated with problems and offer to turn their headaches into projects.

- Finish things. Posters, abstracts, and submitted manuscripts (even to modest venues) count more than grand plans that never leave your hard drive.