The belief that only “positive” research results impress program directors is flat-out wrong.

What PDs actually care about is whether you can think, execute, and learn when reality does not cooperate—which is most of the time in research.

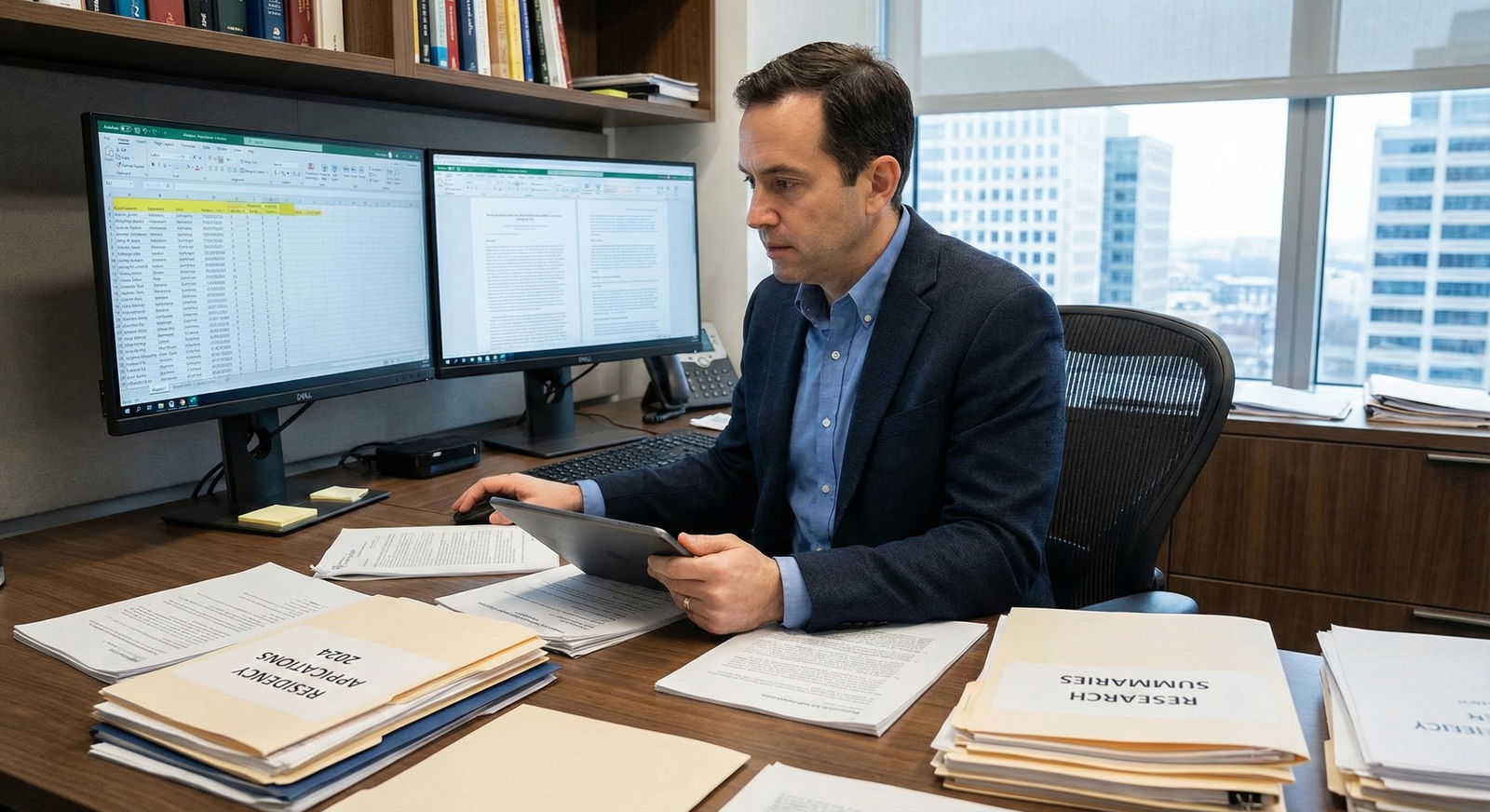

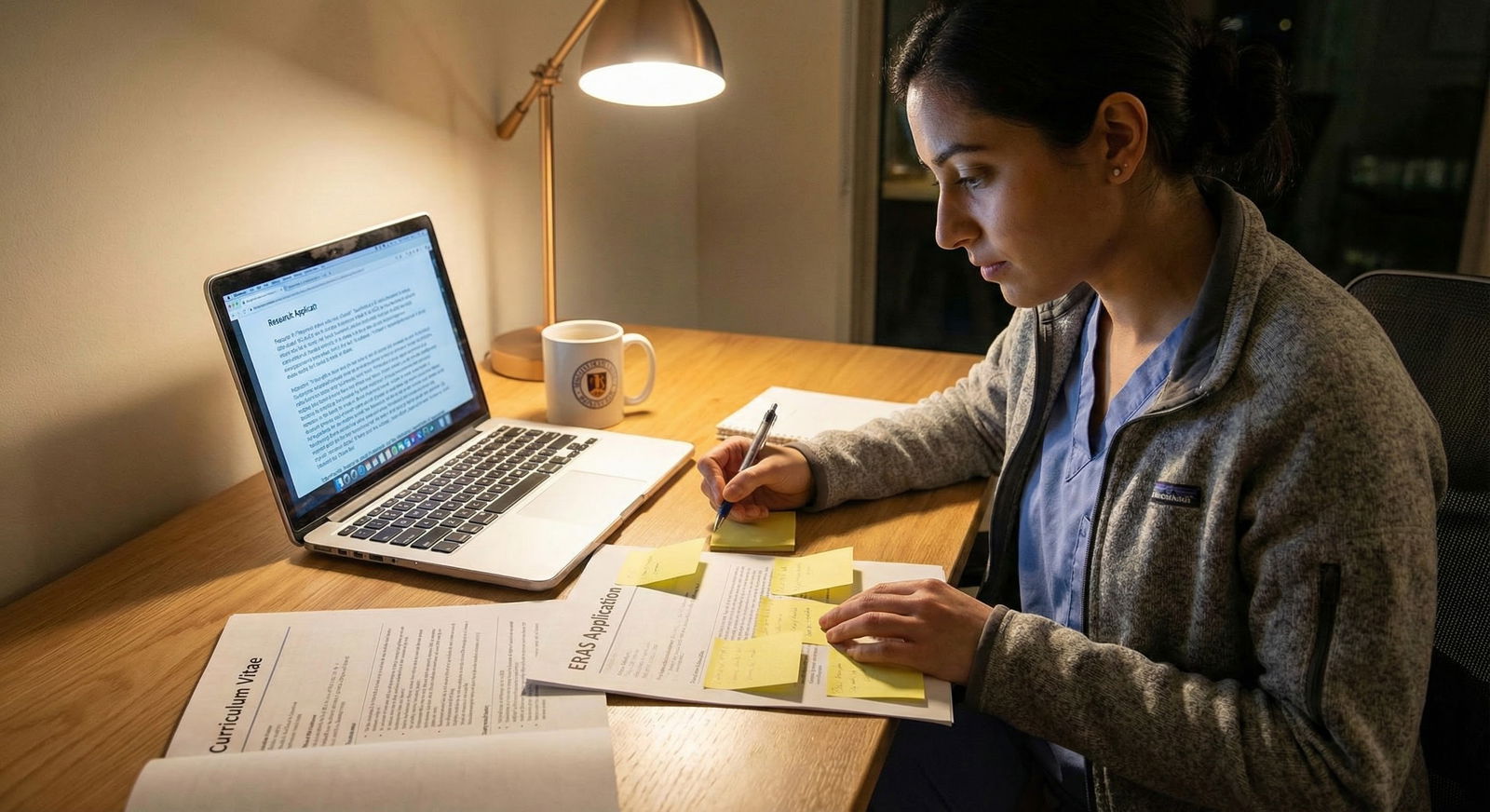

You ran a study, and the outcome was negative, inconclusive, underpowered, or the effect vanished when you did proper stats. Now you’re staring at ERAS, wondering if you should even mention it. You should. And you should know exactly how to spin it—honestly—so it works in your favor.

Let’s walk through how to handle this like an adult researcher, not a panicked MS4.

Step 1: Stop Apologizing for the Result

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Clear positive | 20 |

| Negative | 30 |

| Inconclusive/underpowered | 35 |

| Never finished/abandoned | 15 |

Most residency applicants secretly think:

- Positive = good

- Negative = bad

- Inconclusive = embarrassing

That mindset will ruin your interviews.

Here’s the actual hierarchy in many PDs’ heads, especially at academic programs:

- Completed, honestly analyzed project with a clear learning takeaway (even if negative)

- Completed project, weak understanding of methods or implications (even if “positive”)

- Flashy result with obviously bad methodology

- Ten “projects” you never finished or cannot explain

You’re probably in category 1 or 2. That’s where you want to be.

So first mental shift: your “negative” result is not a flaw. It is raw material. The flaw is being unable to explain it clearly, own the limitations, and show what changed in your thinking because of it.

If you walk into an interview acting like you failed because your p-value was 0.18, you signal to PDs that you do not understand how science works.

Step 2: Understand What PDs Are Actually Looking For

Strip away the noise. When a PD looks at your research section and asks about your project, they’re probing for four things:

- Can you explain the question in plain language?

- Do you understand why the study was designed the way it was?

- Did you see the project through to a reasonable endpoint?

- Can you critically analyze what went wrong or what was learned?

They are not grading you on whether the intervention worked.

An example from a real conversation I’ve heard:

- Applicant A: “Our intervention didn’t show significance, so it was kind of a failure.”

- Applicant B: “We found no statistically significant difference. That forced us to rethink our assumptions about how residents adopt new tools, and we realized our intervention was targeting the wrong barrier.”

Applicant B sounds like a future attending. Applicant A sounds like they memorized the abstract but never thought about it again.

Your job: move yourself firmly into Applicant B territory.

Step 3: Reframe the Story Using a Simple Template

You need a repeatable structure—something you can use in ERAS descriptions, personal statements, and interviews.

Use this four-part framework:

- The Question

- The Approach

- The Result (neutral, not emotional)

- The Takeaway / Next Step

Let’s translate that into a real example.

Bad version (how most students talk about negative projects):

“I worked on a QI project trying to reduce CT utilization in minor head trauma, but we didn’t really see much change and the data was noisy, so it kind of didn’t work out.”

Now the reframed version:

“We asked whether a decision-support pop-up in the EHR could reduce unnecessary CT scans for low-risk head trauma in the ED. We implemented the alert and tracked CT utilization for six months. There was no statistically significant reduction. That result pushed us to look at user behavior logs and we realized clinicians were bypassing the alert quickly, suggesting alert fatigue rather than disagreement with the guideline. It taught me that changing clinician behavior often requires workflow redesign, not just another pop-up.”

Same project. Completely different impression.

For your own project, literally write these out:

- Question: “We wanted to know whether…”

- Approach: “So we designed a study where…”

- Result: “What we found was…”

- Takeaway: “This changed my thinking because…” or “The next logical step would be…”

Once you can say that smoothly, you’re 80% of the way to a strong, positive framing.

Step 4: Fix How You Describe It on ERAS

| Aspect | Weak Description | Strong Description |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Task-based ("collected data") | Question-based ("evaluated whether…") |

| Result | Emotional ("didn't work") | Neutral ("no significant difference") |

| Role | Vague ("helped with") | Specific ("led data cleaning and analysis") |

| Takeaway | None | Clear learning or next step |

Most ERAS entries for “failed” projects read like this:

“Worked on a project studying X. Helped collect data and do chart review. Project did not result in publication.”

That’s a waste of space.

Use the same four-part structure, but tighter and more precise. Example:

“Prospective QI study evaluating whether EHR decision-support alerts could reduce CT imaging in low-risk minor head trauma. Assisted in study design, independently performed data extraction and cleaning from 400+ ED encounters, and conducted preliminary statistical analyses. The intervention did not significantly reduce CT use, leading to a follow-up usability review that highlighted provider alert fatigue and informed redesign efforts.”

Notice what this does:

- Centers the question.

- Names your role clearly.

- States the “negative” result without shame.

- Ends with an insight or consequence.

If space is tight, keep at least: question, role, neutral result.

Do not write: “Study inconclusive.” That sounds like you gave up thinking.

Step 5: Answer “So what happened with that project?” in Interviews

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Interviewer asks about project |

| Step 2 | State the question in 1-2 sentences |

| Step 3 | Briefly describe design and your role |

| Step 4 | State result neutrally |

| Step 5 | Offer 1-2 thoughtful interpretations |

| Step 6 | End with what you learned or would change next time |

Interviewers will absolutely spot the project on your CV that looks the most “meh” and ask about it. It’s almost a reflex.

Use this exact pattern out loud:

- Start with the question.

“We wanted to know whether…” - Then your role.

“My role was mainly…” - Then the outcome.

“When we analyzed the data, we actually found…” - Then the real value.

“That told us that…”

or

“That changed how I think about…”

Here’s a complete example answer:

“We wanted to see whether a standardized discharge checklist could reduce 30-day readmissions for heart failure patients. It was a prospective QI project on the medicine service. I helped refine the checklist items, coordinated with nursing, and did the run-chart analysis each month. When we looked at 6 months of data, readmission rates were not significantly different from baseline. We were a little disappointed at first, but digging into chart reviews we realized the bigger problem was follow-up access—many patients never made it to clinic within 7–10 days. That shifted my thinking: our checklist wasn’t bad, it was just targeting the wrong failure point in the system. It made me appreciate that good QI needs a clear understanding of the full care pathway, not just inpatient processes.”

That answer signals:

- Systems thinking

- Emotional maturity (no whining)

- Ability to handle disappointment

- Real understanding of the clinical context

If they push: “So was it a failure?” you can say:

“The original metric, yes: we did not reduce readmissions. But the project successfully exposed a larger bottleneck in our system—outpatient access—and that insight was valuable to our division for planning the next intervention.”

Notice: you acknowledge reality. You don’t pretend it was secretly fantastic. You just refuse to equate “no effect” with “waste of time.”

Step 6: Talk About Limitations Without Sounding Clueless

There’s a sweet spot with limitations:

- Too vague: “small sample size” for everything = you didn’t really analyze it.

- Too defensive: “we couldn’t control for anything because it was retrospective” = you’re justifying, not thinking.

- Too self-blaming: “we messed up” = you sound careless.

Aim for precise, neutral, and paired with a fix. For example:

Instead of:

“The project was underpowered and that’s why it was negative.”

Try:

“Our main limitation was sample size. We originally planned for 200 patients but only enrolled 110 in our timeframe, which reduced power to detect modest differences. If repeating the project, I’d push for multi-site collaboration or adjust the inclusion criteria to improve accrual.”

Or:

“Because the study was retrospective, confounding is a concern.”

Try:

“Since this was a retrospective chart review, we were limited in which variables we could reliably capture. We adjusted for comorbidities and age, but could not account for factors like socioeconomic status or outpatient adherence, which likely influence outcomes. A future prospective design could better capture those.”

That’s how you sound like someone who can do academic work during residency without hand-holding.

Step 7: Decide When to Include a Truly Messy Project

Some projects really are a mess. IRB fell through, database got corrupted, mentor ghosted you, the whole thing collapsed.

Should you list it? Depends on one question: Is there a coherent story and endpoint?

A negative or inconclusive result is fine; an abandoned half-project with nothing learned is not.

Ask yourself:

- Did we reach a clear analytic endpoint, even if null?

- Did I gain skills (stats, IRB, REDCap, survey building, etc.) that I can explain?

- Can I succinctly state what we’d do differently next time?

If yes, include it and frame the skill gain and thinking.

If no, either:

- Leave it off, or

- Bury it as a brief “research assistant” experience with tasks, not as a full “project.”

Example of the latter:

“Assisted with data abstraction for a retrospective study on outcomes in X condition; responsibilities included chart review using predefined criteria and structured data entry into REDCap.”

Do not pretend it led to big conclusions or publications if it did not.

Step 8: Use “Negative” Projects Strategically in Your Personal Statement

You do not need to write a research manifesto. But one well-chosen negative/inconclusive project can make a powerful short vignette showing growth.

Tight structure:

- Briefly set up the project and your expectation.

- Describe the unexpected or null result.

- Describe how that changed how you think about patients / systems / evidence.

- Connect to why that matters for the kind of resident you want to be.

Concrete example (condensed):

“During my third year I joined a project studying whether a standardized note template would improve documentation quality in sepsis patients. I expected clear improvement; instead, our scoring system showed no meaningful change after implementation. Reviewing individual charts, I realized many of the notes were technically ‘complete’ but still missed the clinical nuance of a decompensating patient. That experience taught me that checkboxes and templates can only go so far, and that real clinical excellence depends on synthesis and anticipation, not just documentation. It is part of why I am drawn to internal medicine, where interpreting subtle changes over time can make the difference between catching deterioration early or missing it entirely.”

Short, specific, shows reflection. No groveling.

Step 9: Be Ready for the “Publications” Conversation

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No research | 15 |

| Research, no pubs | 45 |

| 1-2 pubs | 30 |

| 3+ pubs | 10 |

If your negative/inconclusive projects never got published, you’ll be tempted to apologize. Don’t.

When asked “Did that project get published?” use this approach:

If it did not and probably never will:

“We presented it as a poster at our local research day, but given the small sample size and null findings, my mentor decided not to pursue manuscript publication. The main value for me was learning the full process—from IRB through data analysis—and wrestling with what to do when the data doesn’t support your initial hypothesis.”

If it is in limbo:

“We’re in the process of revising the manuscript after initial feedback; the primary result is negative, so we’re working on better articulating what that adds to the existing literature.”

If they push: “So you did all that work and didn’t get a paper?” you can calmly respond:

“I used to think the only measure of a project was a publication line. After this, I appreciate that negative data, when honest and well-analyzed, still shapes how a department approaches a problem—even if it only lives in internal presentations. For me personally, the project sharpened my skills with [X method/analysis] and taught me how to close the loop on a study.”

This is how you avoid sounding bitter or naive.

Step 10: Quick Self-Audit Checklist Before You Submit ERAS

Before you submit, run every “negative” or “inconclusive” project through this checklist. If you cannot answer “yes” to most of these, fix the description or consider dropping it:

- Is the research question clearly stated in 1–2 lines?

- Does your role go beyond “helped with” and “collected data”?

- Is the result described neutrally, without apology or drama?

- Is there at least one concrete takeaway or implication?

- Could you explain the study design and limitations for 2–3 minutes without getting lost?

- If an interviewer bluntly asked, “So this didn’t work?” would you know exactly how to answer confidently?

If you are ready on those points, your “unsuccessful” project is now an asset.

FAQ

1. Should I still list a project if it completely failed and we stopped it early?

List it only if there is a coherent story and real work completed. For example, you did IRB, substantial data collection, maybe even preliminary analysis, and then discovered a fatal flaw or feasibility problem. In that case, you can frame it as: “I learned X about study design / feasibility / stakeholder engagement, and here’s what I’d do differently.” If the project died at the idea stage or after 3 charts reviewed, leave it off or roll it into a generic “research assistant” role.

2. What if my only research experience is one small, negative project—will that hurt me?

Not automatically. For most non-ultra-competitive specialties and community programs, a single, well-explained project is perfectly acceptable. The danger is not the negative result; it’s sounding like you barely understood or cared about the project. If you can walk through the question, design, result, and what you learned—crisply and confidently—you will look better than someone with ten superficial “positive” projects they can’t explain.

3. How do I handle a mentor who is embarrassed by the negative result and doesn’t want me to talk about it?

You do not need your mentor’s emotional blessing to claim the work you did. You should, however, be accurate about the status: don’t say “manuscript in progress” if it’s dead. You can say, “Our main analysis showed no effect; my mentor decided not to pursue publication, but I presented the work at X venue and it solidified my interest in Y.” If you’re worried about politics, keep the tone neutral and professional—focus on your learning and the science, not on your mentor’s decision. With these pieces in place, you’re ready to use even your messiest projects as proof that you can think like a physician. How you leverage that on the interview trail—that’s the next move.