The idea that needing therapy or meds makes you weak is complete garbage—and it’s also how people quietly break.

I’m just going to say what’s probably already running through your head on a loop:

“If I can’t handle residency without therapy or meds, maybe I’m not cut out for this.” “What if my co-residents find out and think I’m unstable?” “Will this screw me for fellowship? Licensing? Credentialing?” “Everyone else seems tired but managing. Why am I falling apart?”

I know that voice. The one that turns normal human struggle into some kind of moral failure. The one that looks at therapy and medication not as tools, but as evidence that something is fundamentally wrong with you.

Let’s pick this apart. Because right now, you’re probably not actually asking, “Should I get help?”

You’re asking, “If I need help, does that secretly prove everyone’s worst fears about me are true?”

The brutal reality of residency (you’re not imagining it)

Residency is not normal life stress. It’s not “busy season at work.” It’s structurally unhealthy.

You already know the list, but let’s name it, because otherwise your brain keeps saying, “Other people deal with stuff too. Maybe I’m just weak.”

- 24+ hour calls where you’re expected to make life-and-death decisions at 3 a.m. on a brain powered by cold coffee and anxiety.

- Constant evaluation. Every note, every order, every hesitation feels like a test.

- Shifts that end three hours after they’re supposed to, with attendings still asking, “Can you just see one more?” while you haven’t eaten since 8 a.m.

- Being paged about pain meds and potassium while you’re literally in the bathroom.

- Watching people your age die. Telling families their person isn’t coming back. Walking out of that room and going directly into the next one like nothing happened.

None of that is “oh, you just need better coping skills.” That’s a level of sustained pressure that would wreck pretty much any normal nervous system over time.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Sleep problems | 80 |

| Exhaustion | 75 |

| Anxiety | 60 |

| Depressive symptoms | 40 |

| Burnout | 50 |

If you feel like you’re unraveling, that doesn’t mean you’re weak. It means your brain and body are doing exactly what they’re wired to do under chronic overload: they start throwing alarms.

You’re not failing residency. Residency is failing to be humane.

The “if I were stronger, I wouldn’t need help” lie

Let’s get specific about the thoughts that land you here—questioning therapy and meds.

They usually sound like this:

- “My senior is also exhausted and they’re not seeing a therapist.”

- “I chose this. I knew it would be hard. I don’t get to complain.”

- “If I need meds to function, that means I can’t handle being a doctor.”

- “Patients have it worse. I’m just being dramatic.”

I’ve watched residents literally say, “I don’t deserve to be depressed, my life is fine on paper.” While working 80 hours a week and crying in their car before sign-out.

Here’s the part that messes with you: medicine low-key rewards self-neglect. You get praised for pushing through, for staying late, for picking up extra shifts, for never saying no. You don’t get praised for leaving on time, going to therapy, or saying, “I’m not okay.”

So your brain learns a sick equation:

Suffering quietly = strong

Needing help = weak or unstable

That equation is wrong. But it’s everywhere. Attendings who brag about “back in my day we did Q2 call and survived.” Co-residents whispering about “that intern who took time off for mental health.”

It makes asking for help feel like stepping onto a stage under a spotlight.

Here’s my take, and I’m not sugarcoating it:

Refusing therapy or meds because you’re afraid of “weakness” isn’t strength.

It’s fear. Fear dressed up as grit.

Real strength is saying, “Okay, this is wrecking me. I’m not waiting until I fully break.”

What therapy actually is (and what it’s not)

Therapy in residency is not lying on a couch unloading childhood trauma for three years (unless you want to). Most residents don’t have the time or emotional bandwidth for that anyway.

What it tends to look like:

- 45–60 minutes maybe twice a month

- A place where, for once, you don’t have to be “the doctor”

- Someone who doesn’t need you to be the high-functioning golden child

- Concrete skills: how to sleep after night shift, how to not replay every mistake until 3 a.m., how to actually set boundaries with your program without burning yourself

I’ve heard residents say things like:

“I can’t tell my co-residents I’m drowning, because they’re drowning too.”

“I tried to talk to my mom, but she just said ‘you always wanted to be a doctor.’”

“My partner is supportive, but they don’t really get why I’m still thinking about that code five days later.”

Therapy is the one place where you don’t have to edit that.

Is every therapist good with residents? No. Some don’t understand call schedules, charting overload, or the reality of being paged 30 times in an hour. Sometimes you have to “shop” around. Annoying, yes. But that doesn’t make the whole idea of therapy pointless.

The resident version of therapy often hits very specific things:

- Survivor guilt after a bad outcome

- Fear of being “found out” as incompetent

- Obsessively checking the EMR for your patients even when you’re off

- The sick mix of resentment + guilt when you start to hate going to work

- Feeling nothing with patients because you’re so burned out you’ve gone emotionally numb

If you’re asking, “Do I need therapy?” here’s a simpler framing:

If you had a patient living your life, seeing what you see, sleeping the way you sleep—would you be even slightly surprised they wanted support?

Exactly.

Medications: the nuclear option, or just… a tool?

Let’s talk meds, because this is where the shame really ramps up.

“I can handle this without meds.”

“If I start an SSRI, I’ll never get off it.”

“What if program leadership somehow finds out and thinks I’m unstable?”

“What if this shows up on some form and screws me later?”

Deep breath.

First, the obvious but important thing: this is never a DIY decision. I’m not telling you to start anything; I’m telling you that needing or benefiting from meds isn’t a moral failure or a professional death sentence.

Residents end up on meds for very predictable reasons:

- They’re so anxious they’re throwing up on the way to work

- Panic attacks in the call room between admissions

- Can’t sleep even when off, brain constantly replaying every near-miss

- Depressive episodes where getting out of bed feels like moving through cement

- Passive “I wish I’d get hit by a car so I wouldn’t have to go in” thoughts that are getting a little too frequent and a little too real

Does this happen to “strong” residents and chiefs and future fellows? All the time. You just don’t see it because no one wears a sign that says “on sertraline, doing my job just fine.”

The real fear is this:

“If I need meds to cope with this, what does that say about me?”

Here’s what it says: your brain is a human brain reacting to chronic, structural stress with actual biochemical changes. Sleep deprivation alone wrecks mood regulation, impulse control, and anxiety tolerance. That’s before we even talk about trauma, loss, humiliation, or shame.

Meds don’t erase the system being broken. They give your nervous system enough stability so you’re not white-knuckling your existence 24/7.

Some residents do 6–12 months on an SSRI while in their worst rotations. Some stay longer. Some use them to get out of a hole and then taper with supervision. None of that is a character indictment.

“Will this ruin my career?” The licensing/credentialing panic

Let’s go right at the nightmare scenario you’re probably replaying:

“I see a therapist or take meds. Later, a licensing board or hospital asks something about mental health. I say yes. They flag me. I’m screwed.”

You’ve probably heard horror stories, most of them half-remembered, third-hand, and a decade old.

Reality: things are changing. Slowly and imperfectly, but changing.

Most state medical boards and hospitals are getting pressured to stop asking about history of mental health treatment and to only ask about current impairment.

That distinction matters. Immensely.

| Type of Question | What It Usually Means For You |

|---|---|

| Ever had mental illness? | Becoming less common; often being revised |

| Currently impaired by a condition? | Focuses on function, not diagnosis |

| Currently using substances impacting work? | About safety, not therapy/SSRI use |

| Under current monitoring agreement? | Refers to formal programs, not routine therapy |

| Have you sought help to maintain wellness? | Sometimes framed positively |

Most boards don’t care if you once had depression in intern year and got therapy and meds and functioned well. They care if your condition is currently impairing your practice or if you’re unsafe.

Will you need to pay attention to wording when you fill these out? Yes.

Is it smart to know your state’s exact phrasing? Also yes.

Does getting therapy or starting meds automatically brand you as “impaired”? No.

There’s risk either way. You know what else is a risk? Ignoring escalating depression until you’re making dangerous mistakes or end up in an ED with suicidality. Boards care a lot more about that outcome than “this resident took care of themselves early.”

“Everyone else is handling it. Why can’t I?”

I hate this one because it feels so personal. You walk into sign-out half-dead, and someone’s joking about their third 24 in a row. You scroll social media and see your classmates posting about cases, awards, conferences. You assume they’re tired, sure, but ultimately fine.

You don’t see:

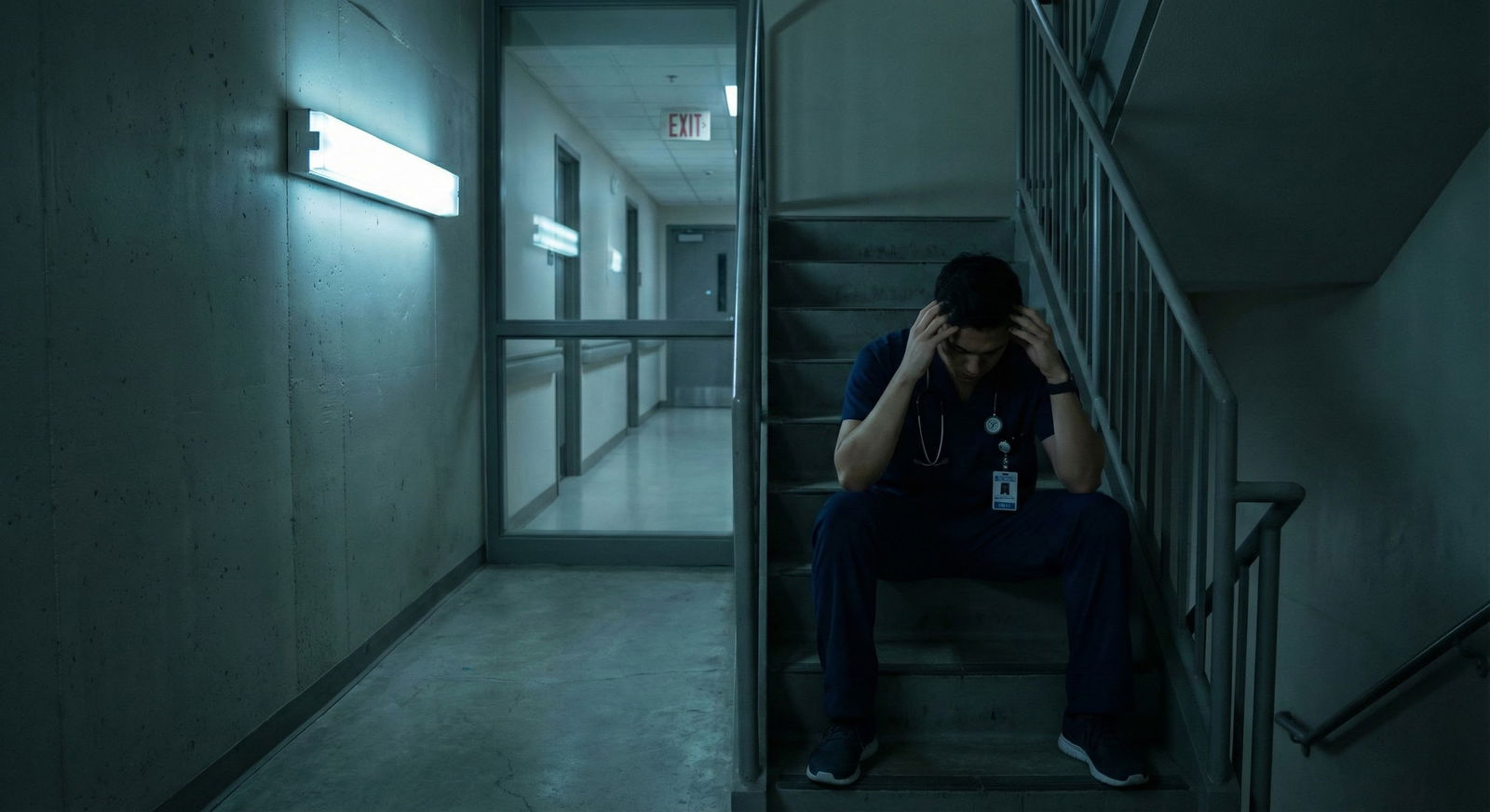

- The resident crying in the stairwell at 2 a.m. because a patient yelled at them and it was the last straw.

- The chief secretly on leave for “family reasons” that are actually panic attacks.

- The co-resident who started meds after a near-suicide they never told you about.

- The one who’s functioning… but only by completely numbing out and drinking every day off.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Resident feels overwhelmed |

| Step 2 | Overwork more |

| Step 3 | Ignore symptoms |

| Step 4 | Trusted friend or therapist |

| Step 5 | Worse burnout |

| Step 6 | Consider quitting or breaking |

| Step 7 | Support, therapy, or meds |

| Step 8 | Better coping and stability |

| Step 9 | Talk about it? |

The people you think are “fine” might be doing way worse than you, they just hide it differently. Or they genuinely have a different threshold. Different brain chemistry. Different support system. Different timing. You don’t invalidate your distress because someone else is managing differently.

Here’s the ugly truth: some people do white-knuckle their way through residency without ever seeking help. But you never see the long-term cost. The divorces. The alcoholism. The attendings ten years later who are bitter, cynical, and detached, but hey—they never saw a therapist, so I guess they “won.”

Is that really the version of “strong” you’re trying to model your life after?

How to get help without setting off every alarm in your brain

You probably want some kind of “Okay, but what do I actually do?” that doesn’t require publicly tattooing “I’m struggling” on your forehead.

Think small, quiet, practical.

Find one safe person in your program ecosystem. Not necessarily your PD. Maybe a chief, a senior, or a faculty member, especially someone who has hinted at being human themselves. Sometimes you can test the waters with something like, “This rotation has been hitting me harder than I expected,” and see how they respond.

Use resident-focused services where you can stay more anonymous. Many hospitals and universities have “employee assistance” or confidential counseling. Is it always perfectly set up? No. But it’s a starting point.

Look for therapists who actually know what residents are. You’re allowed to ask, “Do you have experience working with medical trainees?” If they spend half the session explaining to you that you just need to “prioritize self-care” while you’re literally on 28-hour call, they’re not your person.

If meds might be on the table, talk to someone not in your direct chain of command. A primary care doc outside your institution. A psychiatrist who doesn’t work for your program. Telehealth, if that’s an option where you are.

And yeah, document for yourself that you’re functioning. Not for paranoia’s sake, but for your own brain. “I’m working, I’m safe, I’m seeing a therapist/PCP, I’m taking care of myself.” That reality-check is useful when your shame-spiral starts screaming that you’re broken.

You’re not weak. You’re reacting like a human in an inhuman system.

Here’s the bottom line you probably don’t believe yet, but I’m going to say anyway:

Needing therapy or meds in residency says nothing about your worth as a future physician.

It says everything about the weight you’re carrying and the fact that you’re still trying to show up.

Weakness isn’t shaking in the bathroom between pages. Weakness is letting shame stop you from reaching for things that might keep you alive, functioning, and even—eventually—okay.

You’re not failing because you’re asking, “Do I need help?”

You’re failing if you pretend you’re fine until your body or your mind decides for you that you’re not.

And honestly? The residents I’d trust with my family are not the ones who brag about never needing help. They’re the ones who know what it costs to keep going—and choose not to do it alone.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No Support | 80 |

| Late Support | 55 |

| Early Support | 30 |

FAQ: “Am I Weak If I Need Therapy or Meds to Cope With Residency Burnout?”

1. Will getting therapy or meds show up on my record and hurt my future career?

Seeing a therapist or taking meds for anxiety/depression doesn’t automatically go on some giant “doctor blacklist.” Your medical record is private. Licensing boards and credentialing bodies are increasingly focusing on current impairment, not past treatment. That means they care if you’re currently unsafe to practice, not whether you once needed an SSRI in PGY-2. You should know your state’s exact licensing questions, but getting help early is usually protective, not harmful.

2. What if my program finds out I’m in therapy or on meds and thinks I can’t handle residency?

Most programs don’t have automatic visibility into your private medical care. Employee health and outside providers aren’t emailing your PD every time you talk about burnout. If you take formal leave or need accommodations, leadership may become aware you’re struggling—but many PDs would rather know early than deal with a full crash later. Quietly getting support is not the same thing as announcing “I’m unfit to train.”

3. How do I know if I “really” need therapy or meds versus just being tired like everyone else?

Ask yourself a harsher question: if a patient lived your exact schedule, sleep pattern, anxiety level, and emotional state, would you think they deserved support? If you’re crying multiple times a week, having panic symptoms, thinking “I wish something would happen so I wouldn’t have to go in,” feeling numb with patients, or unable to recover even on days off—that’s not “just tired.” That’s your system starting to fray, and it deserves more than, “I’ll suck it up.”

4. Could I lose my license or be blocked from getting one because I took meds for depression in residency?

Extremely unlikely, especially if you’re functioning and not impaired. Modern standards are shifting hard away from punishing people for seeking care. Many boards have been sued or pressured into changing intrusive questions. Most now ask about conditions that currently impair your ability to practice safely, not whether you ever saw a therapist at age 27. The much bigger threat to your license is ignoring serious symptoms until you’re practicing unsafely.

5. Does needing help mean I’m not cut out for this career long term?

No. Needing help in residency usually means you’re a normal human reacting normally to chronic, extreme stress. Some of the best attendings, chiefs, and fellows I’ve seen have had seasons where therapy or meds were the only reason they stayed afloat. If anything, people who know their limits and get help tend to last longer without becoming bitter, detached, or reckless. Being “cut out for this” doesn’t mean you never struggle. It means you don’t abandon yourself when you do.

Key points, stripped down:

- Therapy and meds don’t make you weak; pretending you’re fine while you fall apart does.

- Residency is an inhuman system; human reactions to it aren’t a character flaw.

- Getting help early protects both you and your career more than white-knuckling ever will.