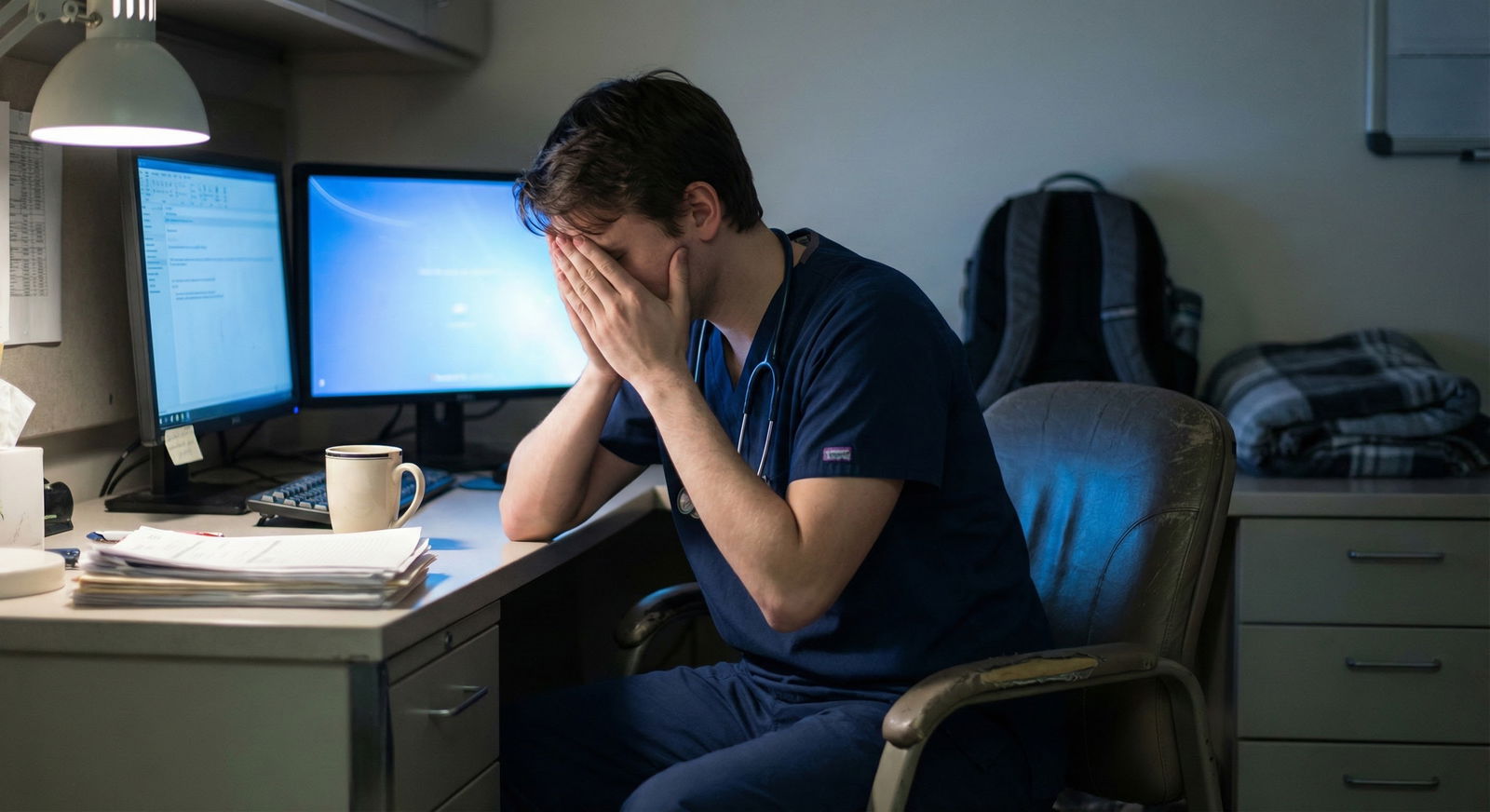

You’re halfway through a call month. Your post‑call “sleep” was three hours of staring at the ceiling. You snapped at a nurse at 3 a.m. and felt like a jerk immediately. You’re asking yourself a question every resident eventually hits:

“Is this just what residency feels like… or am I actually burning out and need to do something?”

Let me be blunt: some degree of exhaustion and emotional strain is baked into residency. But no, constant misery is not “part of the job.” There is a line where “normal hard” becomes “dangerous burnout,” and you need to be able to see it before you cross it.

This is your line-in-the-sand guide.

First: What’s Actually “Normal” in Residency?

There are predictable stressors almost everyone feels at some point:

- Being tired most days, especially on inpatient or call rotations

- Feeling overwhelmed when you’re learning a new service

- Having occasional “I hate this” days or weeks

- A dip in empathy late in long shifts (“I just can’t care about one more thing right now”)

- Doubting yourself when something goes wrong (or almost does)

Those show up, then they usually recede between rotations or vacations. The key word: fluctuate.

Here’s the pattern I’d call “expected but tolerable”:

- You feel worse on heavy rotations and better on lighter ones

- Days off actually help a bit

- You still have moments of satisfaction or pride at work

- You can still enjoy something outside work at least weekly

- Your attendings and co-residents don’t seem worried about you

If that’s you, you’re stressed and tired, but likely not in true burnout territory yet.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Tired most days | 80 |

| Some dread before shifts | 60 |

| No joy in anything | 15 |

| Persistent numbness | 25 |

| Occasional self-doubt | 70 |

| Frequent thoughts of quitting | 30 |

Where “Normal Hard” Ends and Burnout Starts

Burnout isn’t just “I’m tired” or “this rotation sucks.” It has three main dimensions, and the more of these you’re checking off, the less we’re talking about normal:

- Emotional exhaustion – you feel drained, used up, nothing left.

- Depersonalization – patients become “the appy,” “the psych in 12,” not people.

- Reduced sense of accomplishment – feels like nothing you do matters or is good enough.

The key is degree and duration.

Here’s a simple mental framework I use with residents:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Feeling worse than usual? |

| Step 2 | Consider burnout - act now |

| Step 3 | Monitor and use basic coping |

| Step 4 | Only on heavy rotation? |

| Step 5 | Better on days off? |

If your symptoms…

- Last more than 4–6 weeks, across different rotations

- Do not improve with a lighter week or a post‑call day

- Start affecting your patient care, safety, or relationships

…you’re no longer in the safe zone.

Concrete Red Flags: When You Need to Act, Not Just Cope

You want specifics. Here they are. These are clear “this is not just residency” signs.

1. Mood and Motivation Red Flags

Act if you notice any of these for >2 weeks:

- You wake up dreading work every single day, including lighter days

- You feel emotionally flat or numb almost all the time

- You cry at work or at home several times a week and feel hopeless after

- You’re thinking regularly, “If I got hit by a bus and didn’t have to go in, that’d be fine”

- You no longer enjoy anything: hobbies, friends, even basic comforts

Occasional dread before nights? Normal.

Relentless dread that never lifts? Not normal. That’s burnout or depression territory.

2. Clinical Performance / Safety Red Flags

These are non‑negotiable. If you see them, you act. Period.

- You’re making repeated basic errors you know are below your usual standard

- You find yourself cutting unsafe corners because you “just can’t” double‑check things

- You catch yourself thinking, “Whatever, it’s fine,” when you know it might not be

- Nurses, co-residents, or attendings express concern about your focus or performance

Residents have bad days. I’ve seen post‑call interns misplace an order or forget a phone call. That’s human. But a pattern of sloppiness or indifference? That’s dangerous burnout.

3. Thoughts About Quitting or Escaping

You don’t need to be actively suicidal for this to be serious. Watch for:

- Frequent, detailed fantasies about quitting medicine and disappearing

- Thoughts like “If I got in a minor car accident and had to be out for a month, that’d be ideal”

- You’ve googled “leaving residency” more than once and it isn’t just curiosity

- You’re staying only because you feel trapped or ashamed to quit, not because you see any upside

One bad day thinking “why am I doing this?” is normal.

Thinking “I want out” most days for a month is not.

4. Physical / Behavioral Red Flags

Residency will mess with your body. But there’s a line:

- New or worsening substance use to get through shifts or to sleep (alcohol, benzos, weed, etc.)

- You routinely skip meals, hydration, or bathroom breaks not because you can’t, but because you don’t care

- New or worsening chest pain, GI issues, migraines that clearly track with stress

- You’re isolating: ignoring texts, skipping all social interaction, not even calling family

Quick Self-Check: Should I Be Worried?

Use this as a blunt self‑triage. Honest answers only.

In the last 2 weeks:

How many days did you truly dread going in?

- 0–3 → probably okay

- 4–9 → pay attention

- 10–14 → you need to act

Do days off help at all?

- Yes, I feel somewhat human again → stress/overload

- Not really, I just feel empty or anxious about going back → burnout/depression likely

Have you had any moments of satisfaction or meaning at work?

- Yes → there’s still some reserve

- No → your tank is basically empty

Have others commented on you “not seeming like yourself”?

- No → monitor

- Yes → don’t ignore this

If you’re hitting the “need to act” territory on more than one of these, it’s time to do something more than just “power through.”

What Level of Burnout Requires What Level of Action?

Here’s how I’d break it down.

| Level | Typical Signs | What You Should Do |

|---|---|---|

| Expected Stress | Tired, occasional dread, recover on days off | Basic coping, watch patterns |

| Early Burnout | Most days feel heavy, joy decreasing | Talk to someone, small schedule tweaks |

| Moderate Burnout | Persistent dread, some performance slip | Involve PD/mentor, mental health support |

| Severe Burnout | Safety issues, dark thoughts, no recovery | Urgent professional help, real schedule/leave changes |

Expected Stress: Mild but Manageable

You’re tired, irritable sometimes, but you still:

- Laugh at sign-out sometimes

- Care about doing a good job

- Feel better with a real day off or an easier week

What to do:

Tighten the basics instead of overreacting.

- Sleep when you can; protect your first post-call hours like they’re sacred

- Move your body at least 10–15 minutes on non-call days

- Eat actual meals instead of constant sugar and caffeine

- Keep at least one non-work thing in your week: a show, a walk with a friend, church, whatever

Early Burnout: The Slippery Slope

You’re starting to notice:

- Most days feel like a grind

- You’re more cynical with patients

- You’re not bouncing back on weekends like you used to

This is when residents tell themselves “everyone feels this way” and then get wrecked three months later. Do not ignore this phase.

What to do now, not “after this rotation”:

- Tell one person you trust: co-resident, chief, or faculty mentor: “I’m feeling more burned out than usual and it’s not lifting.”

- Make one concrete adjustment:

- Drop one non-essential committee/side project

- Swap one brutal call night if possible

- Protect one evening a week as 100% off-limits for work

And yes, consider talking to a therapist or counselor already. You don’t need to be falling apart to justify it.

Moderate to Severe Burnout: This Is Where You Must Act

This is when you’re:

- Dreading work daily

- Not recovering on days off

- Noticing performance slip, or feeling dangerously detached

- Having escape or self-harm thoughts (even vague)

This is not “wait and see” territory.

Step 1: Loop in Someone With Real Authority

You need someone who can actually change your reality, not just empathize.

Options:

- Program director

- Associate PD

- Chief resident

- Trusted attending with clout

Be direct:

“I’m not doing well. This is more than just a hard rotation. I’m having persistent burnout symptoms that are affecting [my mood / my performance / my safety], and I need help adjusting my schedule and getting support.”

If your first attempt gets brushed off with “yeah, this rotation is tough for everyone,” escalate. Talk to another faculty member, the GME office, or your institution’s wellness/physician health program. Brushing this off is bad leadership, not a sign you should just suck it up.

Step 2: Get Actual Mental Health Support

I’m not talking about mandatory wellness modules. I mean:

- A therapist or psychologist with physician/resident experience

- Possibly a psychiatrist if your symptoms suggest major depression or anxiety

If your program has free or confidential resident counseling, use it. Those services exist because people crash when they don’t.

If you have:

- Thoughts of self-harm

- Thoughts that others would be better off if you weren’t here

- A plan, even vague, to hurt yourself

That is emergent, not “next week.” You contact:

- On-call psychiatrist

- ED

- Your institution’s emergency resident support line

- National lifeline (e.g., 988 in the U.S.)

I’ve seen residents come back from the edge and finish training successfully after they took this step. I’ve also seen the opposite when they didn’t.

Step 3: Change Something Real About Your Workload

You will not cure serious burnout by meditating for ten minutes and downloading a wellness app.

Real options to discuss:

- Short-term leave (a few days to a couple weeks) if you’re at the breaking point

- Adjusting the next rotation to something lighter or more structured

- Reducing extra call shifts or moonlighting

- Offloading research/admin projects that are optional

Programs can and do do this when they understand this is serious. That’s literally part of their duty to you and to patient safety.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Baseline | 80 |

| Better Sleep | 65 |

| Therapy | 50 |

| Schedule Change | 30 |

What’s Not a Reason to Wait

Residents often delay acting for dumb reasons. Let me cut some of those off.

You do not need to wait if:

“It’s almost the end of the block.”

Burnout does not magically reset on the first of the month.“Everyone else seems to be handling it.”

You have no idea what they’re doing at home, or how close they are to crashing.“I don’t want to look weak / lazy.”

Running yourself into the ground and putting patients at risk isn’t “strong.”“I haven’t made any major mistakes yet.”

The goal is to intervene before that happens.“Other people have it worse.”

Misery Olympics don’t fix your brain.

Practical Daily Checks to Keep Yourself Out of the Ditch

You don’t need a 10-point life overhaul. You need a quick, daily gut check:

Ask yourself on the walk in or on the way home:

“On a scale from 1–10, how close am I to not being safe to practice?”

- 1–4: Okay, just tired

- 5–6: Yellow flag – adjust what you can this week

- 7–10: Red flag – talk to someone today

“Did I feel even one moment of purpose or connection today?”

- If no, consistently for a week → early burnout creeping in

“If a good friend felt the way I do and told me, would I tell them to just push through?”

- If not, then don’t do that to yourself either.

FAQs

1. How much dread before a shift is actually normal?

Normal: feeling a pit in your stomach before nights, ICU, or a known brutal attending, especially at the start of a block.

Not normal: waking up with dread almost every day for weeks, including before relatively easy shifts or clinics, and it doesn’t improve once you’re actually at work. If dread is the default, not the exception, it’s time to act.

2. How do I know if this is burnout vs depression or anxiety?

There’s a lot of overlap. Burnout is more tied to work conditions; depression bleeds into everything. If you feel awful even on vacation, can’t enjoy anything, and have persistent sleep/appetite changes or hopelessness, that’s more depression. The truth: you don’t need to perfectly label it. If your functioning and quality of life are tanking, get mental health help now and let a professional sort out the label.

3. Is it okay to ask for a lighter rotation or schedule change?

Yes. And it’s safer for patients if you do when you’re hitting moderate or severe burnout. You’re not asking for a permanent free pass; you’re asking for a temporary adjustment so you can function at a safe, sustainable level. Good programs would rather tweak your schedule than deal with a major error, a resignation, or a hospitalization.

4. Will talking about burnout hurt my career or fellowship chances?

Handled wisely, usually not. You don’t need to announce it on rounds. You talk privately with your PD or a trusted faculty, focus on safety and your desire to keep performing well, and seek help early. What does hurt careers: unexplained performance crashes, big errors, or leaving suddenly after a silent spiral. Quiet, proactive problem-solving looks mature, not weak.

5. What if my program culture is “suck it up or get out”?

Then you focus on safety and back yourself. Document concerning patterns if needed. Use institutional resources outside the program: GME office, resident council, ombuds, physician health services. Toxic culture does not change the fact that you are a human being with limits. If a place expects superhuman endurance, that’s a mark against them, not against you.

6. What’s the one clear sign I should not ignore, no matter what?

Any thought along the lines of “it would be better if I weren’t here” — even if you think you’d never act on it. That is the brain’s SOS. Combine that with ongoing exhaustion and detachment, and you’re beyond normal residency stress. At that point you stop debating, you reach out: to a friend, co-resident, PD, therapist, or emergency line. You do not try to white-knuckle your way through that alone.

Here’s what I want you to walk away with:

- Hard days and temporary stress are normal; persistent dread, numbness, or safety issues are not.

- If things don’t improve across rotations or days off, you act early, not “after this block.”

- Asking for help and changing your workload is not weakness. It’s how you protect yourself and your patients for the long run.