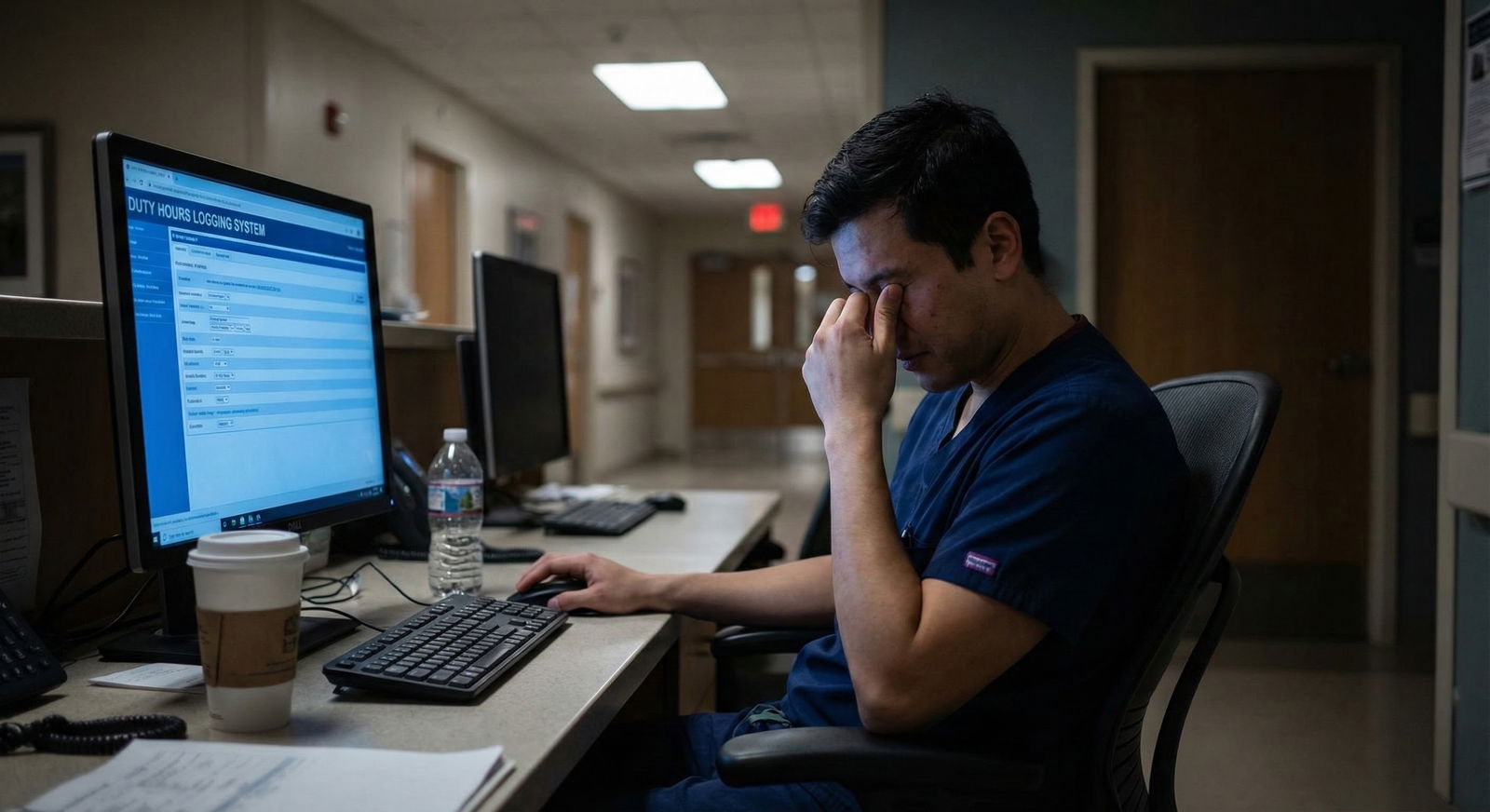

The honest answer: under-reporting duty hours is wrong, common, and dangerous—and you are going to be pressured to do it anyway.

Let me be very clear at the top: you should not under-report duty hours. Ethically, professionally, and for your own long-term sanity, it is a bad move. But you also do not live in a textbook. You live in a residency program where the senior last night said, “Just fix your hours, the ACGME audit is coming,” and your chief quietly hinted, “Make sure nothing flags as >80 this month.”

So you’re stuck between rules, culture, and self-preservation.

This article is about how to think through that. Not in some abstract “duty hour policy” way, but in the real context of:

- Your sleep

- Your evaluations

- Patient safety

- Your program’s politics

Let’s get into it.

The Straight Answer: Should You Ever Under-Report Duty Hours?

No. You should not. And here’s why, bluntly.

Under-reporting duty hours:

- Violates the ACGME requirements you and your program are bound to.

- Falsifies an official educational record (yes, that’s what it is).

- Hides unsafe conditions that put you and patients at risk.

- Protects the institution at your expense.

Residents don’t under-report because they’re unethical. They do it because the system quietly rewards it and punishes honesty. I’ve heard all of these lines, sometimes word-for-word:

- “If we all log accurately, our call schedule will get gutted and your fellowships will suffer.”

- “The ACGME only cares about the numbers, not the reality; just play the game.”

- “If you log over 80, PD will call you in. You sure you want that meeting?”

The reality: programs must adhere to duty-hour limits. If they cannot deliver safe training within those limits, that’s a program problem, not a “you logged too honestly” problem.

You documenting the truth is not the violation. The violation is the condition that made those hours happen.

Why Under-Reporting Is So Tempting (and So Risky)

Residents under-report for four main reasons. I’ll walk through each and what’s actually at stake.

1. Fear of Retaliation or “Being Difficult”

You worry:

- Your evaluations will take a hit.

- You’ll be labeled as “not a team player.”

- The PD will remember your name—in the bad way.

- Fellowship letters will be colder.

Is that fear baseless? No. There are programs where people who speak up get subtly sidelined. But you need to understand the flip side risk: long-term culture and safety.

If everyone lies about duty hours, programs can:

- Claim full compliance during ACGME site visits

- Avoid scrutiny and corrective action

- Continue unsafe or exploitative schedules without pressure to change

That doesn’t just hurt you. It hurts every resident after you. And sometimes it takes only a few honest residents documenting reality to give the Clinical Competency Committee, DIO, or GME office the leverage to force real changes.

2. Wanting to Protect Your Program or Specialty

The story sounds like this:

- “We’re a surgical program; we have to push hard to match you into good fellowships.”

- “If ACGME cracks down, your case numbers will drop.”

- “We’re under review already—be smart with your hours, okay?”

This is guilt-tripping disguised as professional loyalty.

Here’s what’s actually true:

- The ACGME is not trying to shut down good training. They are trying to prevent gross abuse.

- You can have rigorous training and legal duty hours. Plenty of top programs manage this.

- If your program can’t deliver case volume and education without regularly breaking 80 hours, that deficiency belongs on their side of the ledger—not hidden in your timecards.

You owe your patients your best, not your exhausted, cognitively impaired, post-100-hour-week self.

3. Emotional Logic: “I Stayed Late Because I Care”

This one is subtle and honestly, it’s the most dangerous rationalization.

You think:

“I stayed late because I wanted to, to help this family, to get that LP done, to tuck in my patients properly. It feels wrong to log that against the cap.”

Except the cap does not care why you stayed. Chronically crossing 80 hours, or violating 10-hour rest, is still the same level of fatigue and risk whether you were doing heroic work or scut. The rule exists because tired brains make mistakes.

Documenting real hours isn’t a betrayal of your patients. It’s how the system sees:

“This resident wants to do more than the structure safely allows. Maybe we need better staffing, more APPs, better sign-out processes, or smarter cross-cover.”

4. “Everyone Fudges the Numbers, So It’s Harmless”

I’ve literally seen instructions like this during orientation:

- “Log 80 every week. Even if you worked more or less, just keep it clean.”

- “Never log 24+4; make it 24 exactly.”

- “Post-call, don’t log those extra 2 hours you stayed to finish notes. Just round down.”

Here’s the actual harm:

- Your fatigue and burnout get erased from the record.

- National bodies continue to believe compliance is high and fatigue is “solved.”

- Interns learn that dishonesty is the norm. That leaks into everything else.

If you want a culture of honest near-miss reporting and psychological safety, it starts with not lying about the most basic measurable thing: your time.

What You Can and Should Do Instead

You still need a practical way through this. Telling you “just never under-report” without tools is naive. So here’s the actual playbook.

Step 1: Know the Rules Cold

Do not rely on rumors or half-remembered orientation slides. Go straight to your program manual or ACGME requirements for your specialty. At minimum, understand:

| Rule | Standard Limit |

|---|---|

| Weekly hours | ≤ 80 hours, averaged over 4 weeks |

| Max continuous in-house | 24 hours + up to 4 hours for transitions |

| Days off | 1 day off in 7, averaged over 4 weeks |

| Time off between shifts | 10 hours between duty periods |

These are not “goals.” They’re accreditation requirements.

If your program’s expectations conflict with this, they are wrong. Full stop.

Step 2: Log Truthfully by Default

Your default should be: enter what actually happened.

That means:

- If you stayed until 9:30 pm to stabilize a crashing patient after a 6:00 am start, those are real hours.

- If you did sign-out at 7:00 pm but charted until 8:15 pm, those are still duty hours.

- If you were home but “on” from your phone for constant triage, that counts.

Don’t self-censor before the system even sees the data.

Step 3: Decide How to Respond to Pressure

You will hear some version of:

“Just make sure nothing flags.”

“Everyone else logs like this.”

“We need to show improvement this quarter.”

You have three broad options. None are perfect.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Comply & Under-report | 55 |

| Quietly Log Accurate Hours | 30 |

| Raise Concerns or Escalate | 15 |

Comply & under-report

- Short-term: you avoid conflict.

- Long-term: burnout remains invisible, unsafe patterns persist, and you’ve now participated in falsifying records.

Quietly log accurately, don’t advertise it

- Short-term: your data reflects reality; might raise flags quietly.

- Long-term: if enough residents do this, patterns emerge that force structural changes.

Log accurately and actively raise the issue

- Short-term: you may get uncomfortable conversations; risk of subtle labeling as “complainer.”

- Long-term: can drive real, documented program changes; protects future cohorts.

Only you can decide how much heat you’re willing to take. But be honest with yourself: choosing option 1 is not neutral—it’s actively propping up a broken pattern.

Step 4: Use the Right Channels (Not Just Venting)

Do not just complain in the workroom and then log 70 hours. That changes nothing.

Here’s a sane escalation ladder:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Notice frequent violations |

| Step 2 | Log accurate hours |

| Step 3 | Discuss with co-residents |

| Step 4 | Talk to Chief Resident |

| Step 5 | Meet Program Director |

| Step 6 | Contact GME or DIO |

| Step 7 | Monitor for improvement |

| Step 8 | Still unresolved |

Specific actions:

- Talk to senior/chief: “Our team has consistently been over 80, even when we’re efficient. Is there a structural plan to address this?”

- Bring it to the program director with data: “Over the last 4 weeks, I logged 84, 88, 83, and 85 hours without doing extra ‘hero’ work. This seems systemic.”

- Use anonymous surveys or GME channels if your program has them.

- Document patterns: which rotations, which shifts, which bottlenecks.

You are not whining. You are reporting a systems problem that directly impacts patient safety and well-being.

Step 5: Choose Your Battles Strategically

Not every tiny deviation is a referendum on your ethics. You will occasionally have a week at 81–82 hours because of a bad call night or an unusual cluster of admissions. That’s what “averaged over 4 weeks” is for.

Focus on:

- Rotations that routinely exceed 80 hours.

- Regular violations of 10-hour rest.

- Post-call days where “you can leave by noon” actually means 3:00 pm weekly.

- Cultural messages like “No one logs more than 80 here.”

If your program is fundamentally safe and responsive, and you’re dealing with a rare one-off chaotic week, you don’t need to turn that into war. Being principled does not mean being inflexible.

The Ethical Core: What Kind of Physician Are You Training Yourself To Be?

This is the part most people skip, but it matters.

When you under-report duty hours, what are you practicing?

- That outcomes justify dishonest documentation “for the greater good.”

- That institutional loyalty matters more than transparent data.

- That patient safety rules are flexible when inconvenient.

Fast-forward 10 years. You’re an attending. There’s pressure to “clean up” a note after an adverse event. Or soft pressure to not report a near-miss because “this could trigger a painful review.”

Your duty-hour choices train your ethical reflex. Are you the person who documents reality, or the person who massages reality to keep the peace?

You cannot be scrupulously honest in everything but the one metric that makes people uncomfortable.

What If You’re Already Under-Reporting?

Many residents reading this have already done it. Probably repeatedly.

Here’s what you do, starting now:

- Stop under-reporting going forward. The best time to correct course is this week, not next year.

- Quietly start logging accurately and see what happens for a month.

- If patterns look bad (chronic >80), bring that aggregate data to someone you trust: chief, associate PD, GME rep.

- Decide in advance what you’ll say if someone confronts you about “spiking the numbers.” Something like:

- “I’ve decided I’m only going to log my actual hours. If the hours are too high, I think that’s something we should address structurally.”

You do not need to confess past under-reporting. You do need to stop participating in it.

A Quick Reality Check: Not Every Program Is Toxic

Some programs:

- Encourage honest reporting.

- Adjust rotations and staffing based on logged hours.

- Explicitly tell residents: “If we’re not compliant, we need to see it in the data.”

If you’re in a place like that, good. Do not undermine that culture by being the person who “keeps things clean.” Use that safety to actually log reality.

If you’re not, and your program punishes honesty, that’s important information about where you are training. It should inform whether you:

- Rank that program highly for fellowship recommendations

- Take on leadership roles there

- Encourage or discourage future applicants you advise

You are allowed to judge a program by how it handles the truth.

FAQ: Duty Hour Honesty – 5 Common Questions

1. What exactly counts as “duty hours”?

Duty hours include any time you’re doing work for the program: patient care, notes, sign-out, conferences, required reading, call from home (if it restricts your activities), and required remote work. If you’re responding to pages, reviewing imaging, or writing notes from home, that counts.

2. Will logging >80 hours get me in trouble personally?

In most well-run programs, no. It triggers review of the rotation or schedule, not a personal punishment. If you’re repeatedly over 80 because you’re chronically inefficient and everyone else is fine, that’s a different conversation. But in the majority of cases, patterns of overage reflect structural issues, not individual failure.

3. Can my program actually be shut down over duty-hour violations?

ACGME rarely jumps straight to shutdown. More commonly they issue citations, require action plans, and do follow-up reviews. Could chronic, unaddressed violations eventually threaten accreditation? Yes. But that is a program problem, not a “you told the truth” problem. Hiding violations delays necessary fixes and can make the eventual consequences worse.

4. What if my senior directly tells me to change my logged hours?

You have options. You can say, “I’m just going to log what I actually worked; if that’s a problem, I’d rather discuss the schedule than change the numbers.” If you feel unsafe pushing back in the moment, you can comply once, then bring the pattern (anonymously if needed) to a chief, PD, or GME officer. Repeated coercion to falsify logs is a serious issue and absolutely something GME wants to know about.

5. Is it okay to “average down” my hours since ACGME averages over 4 weeks?

No. You’re not responsible for doing the averaging physics—your job is to record what actually happened each week. The system and the program will handle the averaging over the defined period. If across four weeks you’re still over 80, that’s not something you fix by gaming the numbers; that’s exactly the kind of pattern that needs visibility.

Open your duty-hour system the next time you log a shift. Before you type anything, ask yourself one question: “Am I about to enter what actually happened, or what I think will keep other people happy?” Then choose the version of yourself you want to be and log accordingly.