What if you’re the resident who completely falls apart on night float and everyone finally realizes you’re not cut out for this?

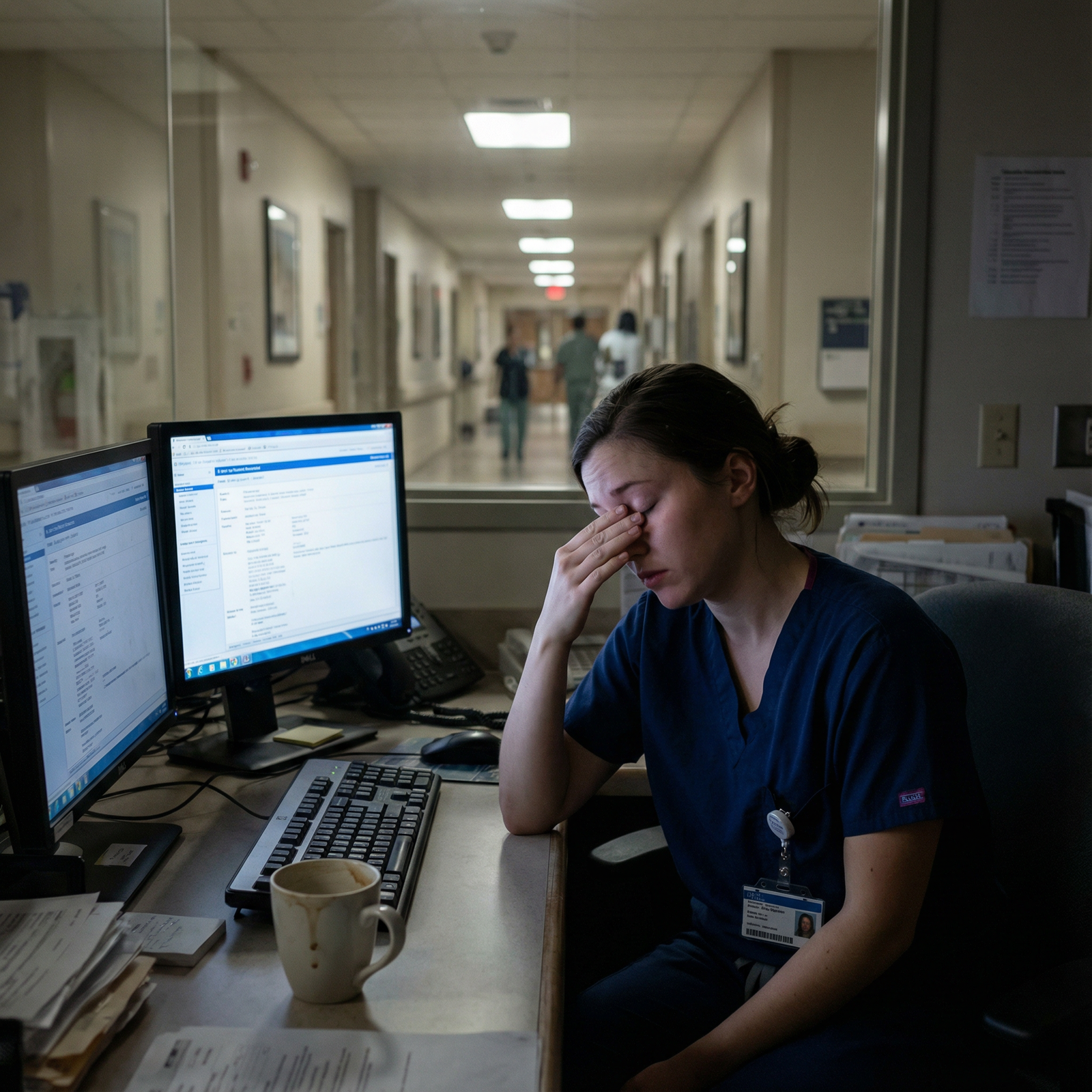

Let’s just say it out loud: the idea of being the doctor in the hospital at 3 a.m. is horrifying. Phones ringing, cross-cover pages, rapid responses, families crying, nurses looking at you like you’re supposed to know what to do when you barely remember your own name.

And then the brain spiral starts:

- What if I miss something subtle and a patient crashes?

- What if I fall asleep at the computer and get written up?

- What if the nurses think I’m useless?

- What if my co-residents are fine and I’m the only one who can’t handle nights?

I’ve watched people go into their first night float month absolutely convinced they were going to break. Some did struggle. None actually broke. And the ones who looked the most “naturally gifted”? A lot of them were just better at faking it.

Let’s walk through what actually makes nights survivable (or miserable), and how you can predict which side you’re likely to land on.

What Night Float Is Really Like (Not the Instagram Version)

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Arrive for Sign Out |

| Step 2 | Get Patient List |

| Step 3 | Cross Cover Pages |

| Step 4 | See Patient Now |

| Step 5 | Batch Tasks |

| Step 6 | Stabilize and Call Senior |

| Step 7 | Check Labs and Orders |

| Step 8 | Document Briefly |

| Step 9 | Pre Morning Sign Out Tasks |

| Step 10 | Give Morning Sign Out |

| Step 11 | Urgent or Routine |

Forget whatever filtered nonsense you’ve seen about “cozy quiet night shifts drinking coffee and studying on downtime.” That happens… maybe two nights a month. On an easy service. In February.

Real night float usually looks more like this:

You show up already tired because your circadian rhythm hates you. Get sign-out on 40–80 patients you’re now allegedly “covering.” Within ten minutes of your senior walking away, someone’s paging you about a blood pressure of 80/40, someone else about a potassium of 2.8, and someone else wants melatonin. You’re trying to remember room numbers while flipping through a list that looks like a ransom note.

Your brain is foggy. Your body wants bed. Instead, you’re supposed to be the calm one.

Here’s the part nobody tells you: almost everyone feels barely in control during their first few nights. The ones who don’t are usually either lying or too arrogant to realize what they’re missing.

So the question “Will I survive?” isn’t really about whether nights are hard. They are. It’s about whether you have—or can learn—the core things that make night work manageable instead of soul-crushing.

The 4 Abilities That Matter Way More Than “Being a Night Person”

You don’t need to be a natural night owl. That’s kind of a myth. What you need are four specific abilities. If you have at least 2–3 of these (or can build them), you’re probably going to be okay—even if it feels like you’re drowning for a bit.

1. You can function while anxious

Notice I didn’t say “you don’t get anxious.” You’re reading this article; you clearly do.

What matters is: can you still do basic tasks while your brain is screaming?

- Can you ask a nurse to repeat information instead of pretending you heard it?

- Can you take 10 seconds to pull up the patient chart instead of guessing?

- Can you say, “I’m not sure, I’m going to call my senior,” without shame?

Residents who implode on nights aren’t the anxious ones. It’s the ones who freeze or fake competence instead of acting.

If you’ve ever:

- Given a presentation while your heart was racing

- Taken an exam while panicking but still finished

- Admitted to a mistake and fixed it instead of hiding it

…then you already have the core skill: acting under emotional noise.

2. You ask for help early rather than late

This one is huge. The residents everyone trusts at night aren’t the superheroes. They’re the ones who consistently over-communicate when things feel off.

If you’re the type who:

- Stews for an hour before asking a question

- Worries your senior will be “mad” you woke them up

- Feels like you need a complete plan before you call

Nights will chew you up until you unlearn that.

A solid “night-safe” mindset sounds like:

“If I’m debating for more than 60 seconds whether to call, I call.”

You’re not there to impress anyone. You’re there to not hurt people. Huge difference.

3. You can prioritize when everything feels urgent

Nights are one big triage exercise. Pages don’t come one at a time, politely. You’ll get:

- “BP 82/50, patient dizzy”

- “Patient pulled out IV and wants to leave AMA”

- “Nurse needs a diet order”

- “Potassium 3.1, what do you want?”

- “Family wants to talk now”

All in five minutes.

You don’t need perfect judgment. You just need basic sorting:

- Will they die in the next 10 minutes if I don’t see them?

- Will they die in the next hour?

- Is this important but can safely wait?

- Is this non-urgent / annoying but necessary?

If you’ve ever:

- Managed multiple competing school deadlines

- Taken care of a sick family member while juggling classes

- Worked any service job during a rush

…you’re already doing a version of this. Nights just make it louder and with more consequences, which is exactly why you lean on your senior early (see #2).

4. You can follow a routine even when you feel awful

Sleep deprivation makes you stupid. Not metaphorically. Actually, cognitively impaired.

The residents who stay safe on nights have rigid little routines they cling to when their brain is mush:

- Always open vitals, labs, and meds in the same order

- Always read the last note before putting in new orders

- Always re-check the patient’s allergies before ordering anything IV

- Always write down your plan in a tiny notebook if you’re walking away

You don’t need to be brilliant at 3 a.m. You just need habits that compensate for the fact that you’re not.

If you’re someone who can:

- Stick to a workflow studying for exams

- Use checklists in the OR or on wards

- Keep a consistent pre-bed routine

You can build “night autopilots” that keep you from making tired mistakes.

How Bad Will It Be for You? A Brutally Honest Self-Check

You’re probably trying to predict your night float future with zero data. So let’s give you some.

| Factor | If This Sounds Like You… | Nights Will Be… |

|---|---|---|

| Speaking up when unsure | You usually ask quickly | Uncomfortable but safe |

| Sleep flexibility | You can nap at odd times | Rough but adaptable |

| Perfectionism level | High and rigid | Emotionally brutal |

| Need for control | Moderate | Manageable |

| Asking for help | Feels acceptable | Much safer |

Now be honest with yourself on a few things:

How do you handle being tired?

Think back to Step studying, overnight call in med school, late ER shifts, or even red-eye flights. Do you turn into a zombie who can’t read a sentence? Or can you push through with coffee and some grumbling?How ashamed do you feel asking “dumb” questions?

If your shame level is sky-high, nights will force a hard reset—or make you miserable until you break that pattern.How bad is your catastrophizing?

You’re reading this as Worried Applicant, so yeah, it’s there. The real question is: can you still move your feet while your brain is screaming? If yes, you can work with that.Have you survived situations you thought would destroy you?

MCAT. Step 1/2. First clerkship. Sub-I. Remember how sure you were that each one would expose you as a fraud? Yet here you are.

None of these by themselves mean you’ll “fail” or “succeed” on nights. They just predict how bumpy your adaptation period will be.

Concrete Things That Make Nights Less Terrifying (Not Just “Self-Care” Garbage)

This isn’t going to be “drink water and set boundaries” advice. You already know that and it doesn’t touch the fear.

Let’s talk about what actually moves the needle.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Sleep routine | 80 |

| Good sign-out | 90 |

| Calling senior early | 95 |

| Caffeine alone | 40 |

| Snacks/hydration | 60 |

1. Script how you’ll talk to nurses and seniors before your first night

A shocking amount of night anxiety is literally “what words do I even use?”

Have a few phrases ready to go. Yes, actually written somewhere.

For a concerning page:

“Thanks for paging. I’m going to come see the patient now. Please repeat the vitals and tell me what changed from earlier.”

For your senior when you’re unsure:

“I’m worried about Mr. X in 12B. Vitals are __, exam is __, I did __ so far. I’m not sure if I should __ or if we need to __.”

You don’t need beautiful wording. You need something to say when your brain is static.

2. Decide your “call the senior” rules before you’re tired

Do this on day 1 of nights. Literally ask your senior:

“Can we go over what you definitely want to be called about tonight?”

Make a list. Things like:

- Any new oxygen requirement or change in mental status

- SBP < 90, HR > 130, new chest pain, neuro changes

- Me debating more than a minute about anything

Then when your 3 a.m. brain wants to “not bother them,” you’ve got a pre-commitment: I promised I’d call for this.

3. Create one or two tiny checklists

Not a 2-page ICU protocol. Something you can glance at while your eyelids are heavy.

Examples:

For any “patient looks worse” page:

- Check vitals and trend

- Check MAR and last 24h meds

- Read last note / plan

- Go see patient

- Re-check vitals yourself

- Decide: can I handle or do I need senior?

You can scribble this on an index card and keep it in your pocket. Tired you will thank past you.

The Sleep / Circadian Nightmare (And How Much It Actually Matters)

You’re probably worried you “can’t function at night” because you’ve always been a morning person.

Honestly? Almost no one functions well at night. That’s kind of the point.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Night 1 | 30 |

| Night 2 | 40 |

| Night 3 | 50 |

| Night 4 | 60 |

| Night 5 | 55 |

| Night 6 | 50 |

| Night 7 | 45 |

What usually happens:

- Night 1–2: Adrenaline carries you, you feel wired but awful.

- Night 3–5: You hit a pseudo-rhythm. It’s not good, but it’s predictable.

- Night 6+: Fatigue debt catches up unless you’re protecting daytime sleep.

Residents who cope slightly better do a few unglamorous things:

- Blackout curtains or an eye mask. Not optional.

- Earplugs / white noise.

- One consistent “sleep window” during the day, even if it’s short.

- Caffeine early in the shift, not at 4 a.m. when you’re almost done.

But here’s the hard truth: you will still feel like garbage sometimes. The goal isn’t to feel great. The goal is to be safe while feeling terrible.

And that circles back to routines, checklists, and calling for backup—not magically becoming a night person.

The Fear That You’ll Be “Found Out” on Nights

Here’s the real fear under all this: nights strip away the illusion that someone else is in charge.

On days, there’s always an attending, a senior, a pharmacist, a herd of people around you. On nights, it’s quieter. When something goes wrong, they call you first.

You’re scared that in that moment everyone will see how shaky you feel inside. That they’ll finally realize you’re the weak link.

Let me tell you what actually happens.

The residents who are respected after a rough night aren’t the ones who “handled everything themselves.” They’re the ones who:

- Called for help early

- Owned their limits

- Stayed kind under pressure

- Showed up for sign-out with honest info, not heroic fiction

I’ve seen interns sob in the stairwell at 4 a.m. and still be trusted by nurses because in between the tears, they came when called, admitted what they didn’t know, and did the work.

If you’re the kind of person who’s anxious enough to be reading about this ahead of time? You are already not the arrogant danger type. That’s… actually a good sign.

How to Know You Will Survive (Even If You Hate Every Minute)

Let’s compress this down.

You will probably survive night float if:

- You’re willing to ask for help when you’re uncertain

- You can follow a basic routine even when you feel like death

- You care enough to worry about patient safety (yes, your anxiety is actually evidence of that)

- You’re not committed to looking smart at the expense of being safe

Will you love it? Probably not. A few people do, most don’t. Many absolutely hate it for the first few weeks and then begrudgingly adapt.

But surviving isn’t about enjoying it. It’s about:

- Not harming patients

- Not destroying your own mental health more than necessary

- Getting through the block and moving on

One more thing: programs know nights suck. That’s why there are usually:

- Night float seniors

- Nocturnists / in-house attendings in many hospitals

- Phone backup even where attendings aren’t in-house

You are not going to be the only doctor on Earth responsible for everything. It just feels that way when it’s dark and quiet and your brain is whispering doomsday scripts.

Your Next Step (Do This Today, Not “Someday”)

Open a blank note on your phone right now and title it:

“Night Float Survival – My Rules”

Write three things:

- “If I debate for more than 60 seconds whether to call my senior, I will call.”

- One tiny checklist you’ll use when a patient “looks worse.”

- One sentence you’ll say to a nurse when you’re not sure what to do yet, like:

“I’m not sure yet, but I’m coming to see the patient and I’ll update you after I assess them.”

That’s it. Three lines.

You just created the start of your personal night float safety net. It won’t fix the fear. But it gives that scared, future, 3 a.m. version of you something to hold onto instead of just white-knuckling pure panic.