The most dangerous thing on call is not the crashing patient. It is the sloppy sign‑out list you inherit and blindly trust.

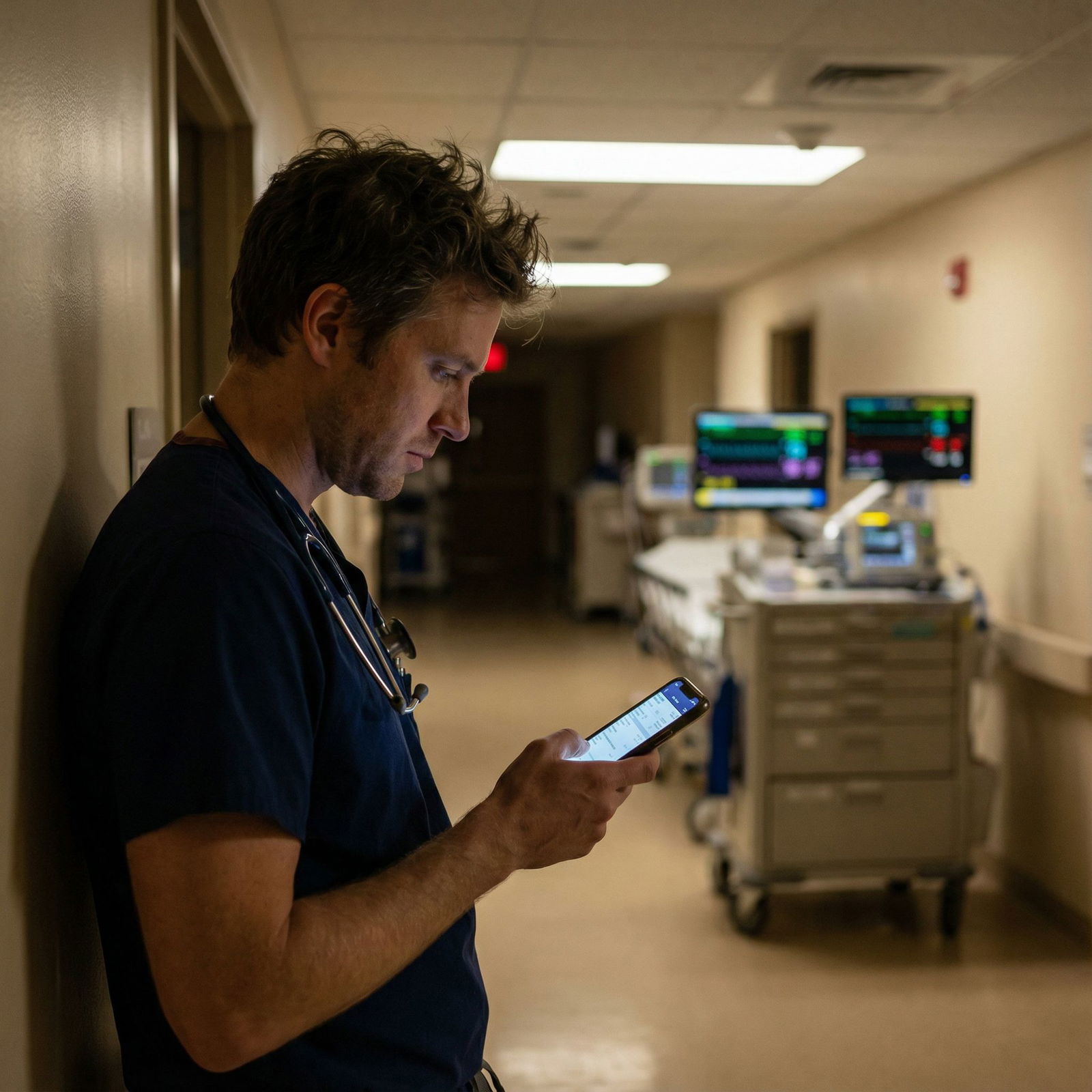

You’re on call. You sit down, get sign‑out, and halfway through you realize: this list is a mess. Vague plans. Unknown labs. “Follow up CT?” with no reason. “Keep an eye on her” with no parameters. Your senior is busy, the outgoing team is already halfway to the parking lot, and you’re holding the bag.

Here’s how you handle that situation without killing yourself (or anyone else).

Step 1: Recognize When the List Is Actually Dangerous

Not every bad sign‑out is dangerous. Annoying, yes. Unsafe, not always. You need to distinguish “ugly formatting” from “patient‑safety landmine.”

Red flags that your sign‑out list is dangerous:

- Lots of “???” or “f/u” with no why or when.

- Orders that are mentioned in sign‑out but not actually in the chart.

- “Soft” hand‑offs: “She’s been tachy all day, just keep an eye on it.”

- Unclear code status or goals of care.

- Isolation or anticoagulation status not mentioned for obviously relevant patients (e.g., new A‑fib, GI bleed, neutropenia).

- Nobody seems to own a major active problem (“cards consulted, awaiting recs” for 3 days).

- Critical labs referenced with no numbers. “Anemia being worked up” and Hgb is actually 6.9.

If two or three of those show up within the first page, you are not just tired and picky. You’re holding a liability bomb.

Your mindset must shift immediately:

You are no longer “covering” comfortably sign‑ed‑out patients. You are actively performing damage control on a high‑risk list.

Step 2: Triage the List Before the Pager Chaos Starts

You do not have time to fix everything. You do have time to prevent the worst disasters.

Right after sign‑out, before you answer the first non‑urgent nursing call, do a 5–10 minute triage pass.

Sort patients mentally into four buckets:

Red – Could die or crash this shift if you miss something.

Examples:- Sepsis, borderline BP, lactate trend unclear

- GI bleed, Hgb “trending down” but no numbers

- New chest pain, “cards to see in AM”

- New neuro change, “waiting on CT”

Orange – Could get significantly worse or need escalation.

Examples:- Uncontrolled pain, hypotension after opioids

- DKA, insulin drip running, but no clear target plan

- COPD on BiPAP, “maybe step down”

Yellow – Stable but with plans that need clarity to avoid 3 a.m. confusion.

Examples:- “Follow up AM labs” with no threshold for action

- “Possible discharge tomorrow if…” with vague criteria

- Abx stop date unclear

Green – Truly stable / social issues / home tomorrow.

Minimal attention unless called.

You’re going to actively investigate Reds first, then Oranges, and just clean up the worst Yellow confusion. Greens get the usual “if I’m called, I’ll respond” treatment.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Red | 40 |

| Orange | 30 |

| Yellow | 20 |

| Green | 10 |

Do not let yourself get sucked into tinkering with low‑risk stuff while high‑risk patients are quietly decompensating in the background.

Step 3: Rapid Chart Recon on the Top 5–10 Risky Patients

You cannot do a full work‑up on 40 patients at 6:45 p.m. You can absolutely do a focused chart recon on the top 5–10 dangerous ones.

For each “Red” and key “Orange” patient, do a fast, ruthless scan:

Open the chart and glance at vitals trend (last 12–24 hours).

- Any hypotension, tachy, desats overnight or afternoon?

- On pressors? High O2 needs? New BiPAP?

Latest labs and imaging.

- Creatinine and K+ for anyone on ACEi, diuretics, or known kidney issues.

- Hgb / platelets if any bleeding concern.

- Trops, BNP, lactate, VBG/ABG if mentioned.

- Scroll to imaging reports: don’t trust “scan fine” in sign‑out.

Active meds and one‑liner.

- Anticoagulation: indication + timing + plan.

- Insulin drips, high‑risk infusions, pressors, opioids in naive patients.

- Note: are they DNR? On comfort care? That changes everything.

Check for pending studies or consults today/tomorrow.

- Any orders that should have resulted but did not?

- Critical things like “MRI brain pending” or “duplex lower extremity pending” for possible DVT.

You are trying to answer one question:

“Is this patient actually more unstable or risky than the sign‑out suggests?”

If yes, you write yourself a quick, clear plan. If not, move on fast.

Step 4: Decide Who You Need to See in Person Pre‑Emptively

You cannot see everyone before the night explodes. You should see some people.

Patients you should physically lay eyes on early, even if no one is calling you yet:

- Anyone with:

- MAPs borderline, but still on the floor.

- Marked tachycardia (>120) or tachypnea.

- New O2 requirement or escalation in last 24 hours.

- Recent rapid response or ICU downgrade.

- Anyone your gut says, “This story isn’t matching the vibes.”

I have walked into rooms where sign‑out said “mild SOB” and the patient was tripodting, diaphoretic, on 6L with RR 30. Because no one had looked at them since noon.

For each in‑person check, keep it short and focused:

- Quick exam: mental status, work of breathing, perfusion, obvious pain.

- Ask nursing: “Has anything changed in the last few hours? Anything you’re worried about that’s not in the note?”

- If they look worse than chart suggests, don’t be a hero. Escalate: call senior, consider higher level of care, place needed orders.

You’re doing preventative work so you’re not running a code on this same patient at 2 a.m.

Step 5: Clean Up the Worst Sign‑Out Ambiguities

You won’t fix the whole list. You need to fix the parts that will burn you overnight.

Ugly but survivable ambiguity:

“Adjust bowel regimen as needed.” Fine. You can handle someone without a BM.

Dangerous ambiguity:

“Follow up CT.” No reason, no timeframe, no what‑if.

Here’s how to clean these up, especially if the day team has gone home:

Use the chart as your primary source of truth.

Look at the last progress note and consultant notes:- If CT was for “rule out PE” and they’re already on anticoagulation and improved, timing matters less.

- If CT was for “new neuro deficit,” you need to know if it was done and act on it tonight.

If the risk is high and something doesn’t line up, call the outgoing resident.

Yes, even if they’re leaving. This is not social. It’s patient safety.Say it like this:

“Hey, quick question about Ms. X you signed out. I just saw her CT head was ordered four hours ago for new neuro changes but still not done, and the note is vague. What exactly were you worried about, and what would you want done if she worsens overnight?”Create your own mini‑plan in your notes or sign‑out for the night:

- “If BP < 90 systolic x2, give 500 cc LR bolus and recheck, then call senior.”

- “If Hgb < 7 overnight, transfuse 1 unit, type and screen already done.”

- “If chest pain recurrs + dynamic EKG change, call cards fellow.”

You are not trying to be perfect. You are trying to erase the “I had no idea what to do” moments at 3 a.m.

Step 6: Protect Yourself Legally and Logistically (Without Being Paranoid)

Bad sign‑out lists are how you end up in QI meetings and M&M slides. You do need to protect yourself, but there’s a smart way to do it.

What not to do:

- Do not rant in the chart about the previous team.

- Do not write passive‑aggressive notes like “inadequate sign‑out.” That just makes you look unprofessional.

What to do instead:

Document your assessment and plan when you meaningfully intervene.

“Called to evaluate hypotension. On review, patient septic with rising lactate. Exam consistent with… Started IVF, broad spectrum antibiotics, discussed with ICU fellow, transferred to ICU.”If you’re handed an obviously unsafe situation (e.g., floor patient on escalating pressors with no ICU consult), call your senior/attending, fix the immediate problem, and then send a brief, factual email later to your chief or PD if this is a recurring pattern. Keep it about systems, not personalities.

Keep a simple personal log after the shift if something was really bad. Date, MRN (or anonymized), what you inherited, what you found, what you did. Not to weaponize, but to jog your memory if this shows up again.

You aren’t trying to build a legal shield. You’re building a track record that you recognized danger and acted.

Step 7: Handle Nursing Calls Strategically When the List Is a Mess

When the underlying sign‑out is weak, the volume and complexity of nursing pages get worse. Because they can feel the chaos too.

You need a triage script in your head, or you’ll drown.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Page from nurse |

| Step 2 | Go now |

| Step 3 | Chart review then bedside |

| Step 4 | Give clear phone order |

| Step 5 | Document and escalate if needed |

| Step 6 | Move to next task |

| Step 7 | Emergent? |

| Step 8 | High risk patient? |

You don’t say this out loud, but you think it:

Is this emergent? (Airway, breathing, circulation, acute mental status change)

Drop everything. Go. Sort details later.If not emergent, is this patient on my Red/Orange list?

If yes, be more conservative. More likely to walk over, check, and adjust plan.If it’s low‑risk + clear ask (pain meds, nausea), handle over the phone with clear instructions and parameters:

“Give 0.5 mg IV dilaudid now; if pain still >7 in 1 hour, page me again. Hold if RR < 10.”

Also: it’s totally fine—and smart—to occasionally say,

“I’m still getting to know this patient because the sign‑out was very limited. I’m going to come see them so we’re all on the same page.”

Nurses will often quietly confirm your suspicion that the team has been a mess. Use their eyes and memory; they’ve been there all day.

Step 8: Use Your Senior and Consultants Wisely (Without Crying Wolf)

Bad sign‑out doesn’t mean you carry it alone. It also doesn’t mean you call your senior for every annoyance.

Times you absolutely should involve your senior early:

- You uncover a major mismatch: sign‑out said “stable CHF” but patient is on BiPAP with rising creatinine and borderline BP.

- You think someone needs a higher level of care (ICU/step‑down).

- You find a probably missed diagnosis, like untreated sepsis or a missed NSTEMI.

- You’re inheriting a truly unsafe “floor ICU” situation.

Phrase it like a colleague, not a panicked intern:

“Hey, I’m looking at Mr. Y from sign‑out. The list says ‘stable, diuresing,’ but he’s actually on 10L, RR 30, creatinine up from 1.2 to 2.3 and SBP 90. I’m worried we’re behind here. Can you come lay eyes with me and help decide if he needs ICU or change in management?”

Most good seniors will appreciate that. You’re not dumping. You’ve already thought it through.

For consultants: if the day team “left it for GI/cards/ID tomorrow” but the situation worsens, don’t hesitate to page the fellow on call. “Day team wanted to wait until morning” is not a reason to let someone crash.

Step 9: Build a Micro‑System So This Doesn’t Crush You Every Time

You will get bad sign‑out again. Different service. Different resident. Same chaos.

So you need a reproducible mini‑system you can run in 15–30 minutes each call start.

Here’s a sample structure you can adapt:

| Step | Time | Task |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 min | Risk sort patients into Red/Orange/Yellow/Green |

| 2 | 10 min | Chart recon on top 5–10 high-risk patients |

| 3 | 10 min | See 2–4 highest-risk patients in person |

| 4 | 5 min | Clarify the most dangerous sign-out ambiguities |

| 5 | Ongoing | Triage calls using your internal algorithm |

You can literally write this on a sticky note in your pocket or on the whiteboard in the call room.

Over time, it becomes muscle memory:

- Sit.

- Sort risk.

- Recon charts.

- See a few critical patients.

- Clear the worst unknowns.

- Then let the night come.

Step 10: After the Shift, Do a Short, Honest Debrief

You survived. Maybe you prevented a crash. Maybe you ran one anyway but at least saw it coming.

Two things you should do after a brutal on‑call with a dangerous list:

Ask yourself: what almost hurt someone?

- What did the sign‑out miss that nearly caused harm?

- What did you catch late that you could catch earlier next time?

- Was there a system failure (no standardized sign‑out, no backup)?

Decide what feedback is actually worth giving.

- If it’s a one‑off lazy day team, direct conversation or nothing.

- If it’s a pattern on a service, talk to your chief or PD with concrete examples:

“On nights this week, I repeatedly inherited patients with no code status documented, and ‘follow up CT’ without indication or contingency plans. This is creating real safety risk overnight.”

You’re not the residency police. But you are part of the system, and you can push it a little better.

Concrete Examples: What To Actually Write and Say

Let me make this painfully practical.

Example 1: The “Follow Up CT?” Disaster

Sign‑out line: “Bed 14 – new headache, follow up CT head. Likely migraine. Stable.”

You open chart:

- Vitals: BP 190/100, new this afternoon.

- Note: “Concern for possible ICH vs hypertensive emergency. CT ordered stat.”

- CT result already in: “Small right basal ganglia hemorrhage…”

What you do:

- Go see patient. Full neuro exam.

- Check meds: any anticoagulation?

- Call neurology or neurosurgery if not already involved.

- Document: “On assuming care overnight, CT head already resulted showing… Neuro exam… Discussed with neurology. Plan…”

- Text/call your senior: “We actually have a new ICH. The sign‑out minimized it; I’ve looped in neuro, but want you aware.”

You just turned “follow up CT” into actual care.

Example 2: The “Watch the Blood Pressure” Nothing‑Plan

Sign‑out: “Bed 9 – sepsis, on zosyn. Borderline pressures, just keep an eye.”

You check:

- MAPs 60–65, lactate 3.2, on 2L NC, HR 115.

- No fluid given in last 6 hours.

- No defined targets or escalation.

Reasonable actions:

- Give a fluid bolus (unless clear contraindication).

- Re‑check lactate.

- Set your threshold: “If MAP < 65 after bolus, will call ICU for possible pressors.”

- Write a brief note or at least leave an EMR comment.

Now “keep an eye” has a brain behind it. Yours.

Common Traps You Need To Avoid

There are patterns that trip even good residents when sign‑out is bad.

Avoid these:

Assuming clarity where there is none.

“They said ‘cards following,’ so I guess it’s fine.” Go check if there are actual recs. Sometimes “cards following” means “we left a consult and waited.”Trying to fix the entire list.

You do not have the bandwidth. Focus on “who can die” and “who can decompensate” first.Over‑trusting “stable” for ICU downgrades.

If a patient came out of ICU that day, and the sign‑out is one line, go see them. Lots of near‑codes live in that category.Avoiding calling for help because you’re embarrassed by how bad the sign‑out is.

Your senior would much rather get one more call than hear about a preventable rapid the next morning.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. What if the outgoing resident gives terrible sign‑out but is PGY‑3 and I’m an intern?

You still protect patients first. Respect hierarchy, but do not be passive. Clarify politely: “Just so I’m clear, what BP would you want me to act on overnight?” If they blow you off, that’s data. Then you do your own chart recon and involve your senior if you uncover something unsafe. Later, debrief with your own senior or chief privately if this is a recurring issue.

2. How much time should I realistically spend on chart review at the start of call?

On a heavy service, you might only get 15–20 minutes. Use it ruthlessly. Pick the top 5–10 riskiest patients and give each 1–2 minutes: vitals trend, latest labs, active issues. Do not scroll notes for sport. You’re scanning for red flags, not reading a novel.

3. Isn’t it overkill to see patients in person if they seem okay on paper?

No. EMR lies by omission all the time. Flowsheets incomplete, vitals lagging, exam copied forward. Especially with new O2 needs, recent ICU downgrades, or vague “keep an eye” instructions — going to the bedside early has saved more residents than any clever algorithm. You do not need a detailed exam on everyone, just a quick eyeball.

4. How do I avoid sounding accusatory when escalating concerns about bad sign‑out?

Keep it about facts and risk, not personalities. “I took over Ms. Z with sepsis, but there was no plan for what to do if her BPs dropped. Overnight she did become hypotensive, and we needed rapid escalation. Can we standardize sign‑out to include clear contingency plans for high‑risk patients?” That sounds like you care about systems and safety, not gossip.

Open your current sign‑out template and add one section called “If X happens overnight, do Y, then call Z” for high‑risk patients. Use it on your next call night, even if nobody else does. That single change will make a bad list much less dangerous.