What do you do when you’re on post‑call rounds and suddenly realize: “That order I placed at 2 a.m. was wrong”?

You’re not the first. You won’t be the last. But how you handle the next 30 minutes says a lot about the kind of physician you’re becoming.

This is the playbook for that exact moment.

Step 1: Stop the Harm First, Analyze Later

You do not start with an email. Or a reflection. Or a root cause analysis.

You start with the patient.

A. Confirm what actually happened

Do not assume the worst or the best. Open the chart and get specific.

Check all of this, quickly but carefully:

- The exact order you placed (dose, route, frequency, timing)

- Whether it was administered (MAR/administration record)

- When it was administered and how many doses

- Current vitals, I/O, and latest nurse notes

- Most recent labs and trending data

You’re answering two questions:

- Was the order actually “wrong” by objective standards?

- Has it reached the patient yet, and if so, how much?

Example:

You meant to order heparin 5000 units subQ BID for DVT prophylaxis. You see “heparin 1000 units/hr IV infusion” in the MAR running for 6 hours. That’s no longer a theoretical problem.

B. Decide: bedside now or call the nurse first?

If the potential harm is anything more than trivial, you go to the bedside. Period.

You physically see the patient right now if:

- The wrong med or dose could affect hemodynamics, breathing, or mental status

- There was a high‑risk medication involved: insulin, anticoagulants, antihypertensives, opioids, sedatives, chemo, electrolytes, pressors, antiarrhythmics, etc.

- The patient’s condition has changed overnight and you’re wondering if your order played a role

If it’s something like:

- An extra 325 mg of acetaminophen but total daily dose is still safe

- A single missed bowel regimen dose

- Slightly early or late timing of a non‑critical medication

…you may not need to sprint to the bedside, but you still need to fix the order and document.

When in doubt and you can physically get there: you go look at the patient.

C. Stop or correct the order immediately

Standing at the computer (ideally after seeing the patient), you:

- Discontinue or correct the incorrect order right away

- Place the correct order clearly

- If a med/infusion is currently running, call the nurse and say plainly:

“This heparin infusion is not supposed to be running on this patient. Please stop it now while I place the corrected order. I will come by.”

Do not silently “clean up” the chart and hope no one notices. That’s how small problems become reportable events.

Step 2: Loop In the Right People – Fast and Clearly

Residents screw this part up all the time. They either over‑broadcast in a panic or under‑communicate out of fear.

You need a tight circle and a clear story.

A. Call the bedside nurse (if you haven’t already)

Tone matters here. Drop the ego.

Script you can basically steal:

“Hi, this is Dr. ___, night resident for ___ team. I just realized the [med/order] I placed at [time] for [patient] was incorrect. I’ve discontinued it and placed the correct order. Has it been given / is it still running? I’m coming by to assess them now.”

Then ask:

- What they’ve observed

- Any changes since administration

- Their concern level

And yes, if this was clearly your error, say that out loud:

“This was my mistake. I’m addressing it now and will update you and the day team.”

People trust you more when you own your stuff.

B. Notify your senior or attending – don’t “wait and see”

I’ve watched interns try to ride it out until sign‑out. Bad idea. You want backup in the loop early, especially if:

- The med was high risk

- There was any change in patient status

- There was actual or potential harm

- A test or procedure was missed or delayed in a way that affects care

How you say it to your senior:

“Hey, quick but important update on bed 12. Overnight I ordered [X] for [reason]. Looking back, that was incorrect because [brief explanation]. It was given once at [time]. I evaluated the patient just now: [vitals, exam, labs, any changes]. I’ve [stopped/corrected] the order and [plan]. I think we should [consider labs/monitoring/consult]. Wanted to loop you in and see if you’d add anything.”

You’re not calling to confess in vague terms. You’re presenting like a mini‑case with an error attached and a clear management plan.

C. Involve pharmacy if it’s med‑related

Pharmacy is not there to judge you; they’re there to keep the patient alive and get dosing right. Use them.

You call pharmacy if:

- There was an overdose or significant extra dose

- You’re not sure about toxicity thresholds

- A reversal agent or antidote might be needed (vitamin K, protamine, naloxone, flumazenil, etc.)

- You’re dealing with narrow therapeutic index meds (digoxin, warfarin, DOACs, tacrolimus, etc.)

Example opening:

“I’m the resident on [service]. I accidentally ordered [drug, dose, route] for [patient, age, weight, relevant comorbidities]. It was given [once / multiple times] at [time]. I’ve stopped it. I want to make sure I’m doing everything I should in terms of monitoring, labs, and potential reversal.”

You’ll sound way more competent asking this than pretending nothing happened.

Step 3: Assess and Treat the Consequences

Now you manage the medicine.

A. Re‑assess the patient as if this was a new problem

Consider this a new consult: “Possible medication error” or “Missed therapy overnight.”

You do:

- Full vital signs review

- Focused exam based on the error (neuro for sedatives, cardio/pulm for BP meds, abdominal for anticoagulant risk, etc.)

- Targeted labs or tests if appropriate

Example: you gave 10 mg IV hydromorphone instead of 1 mg:

- Check respiratory rate, O2 sat, end‑tidal CO2 if available

- Evaluate mental status, pupils

- Prepare naloxone and think about whether you need it now vs close monitoring

Example: wrong insulin dose overnight:

- Check current POC glucoses + trends

- Ask nursing about symptoms (sweating, confusion, tremor, etc.)

- If hypoglycemic, treat according to protocol and adjust further insulin orders

B. Order appropriate monitoring and tests

This is where people under‑react or over‑react.

Do not shotgun labs “just to do something.” Be targeted.

Some typical responses:

- Anticoagulant overdose → CBC, coagulation studies, possibly anti‑Xa, plus close neuro checks

- Extra beta blocker or antihypertensive → telemetry, frequent vitals, hold morning doses, consider fluids, atropine if symptomatic bradycardia

- Renally cleared med in CKD → BMP, drug level if relevant, adjust dose going forward

- Missed antibiotic dose in severe infection → restart promptly, maybe adjust schedule, document

If you’re unsure, talk it through with your senior or pharmacy.

Step 4: Communicate Upfront – With the Day Team and Sometimes the Patient

This is the part people fear the most. They overcomplicate it in their heads.

A. Tell the day team in real time, not as a throwaway line

On rounds, do not bury this in a 3‑minute ramble about overnight “events.”

You want something like:

“For Mr. Smith, one overnight issue to flag: at 1:30 a.m. I mistakenly ordered [drug/dose] instead of [intended order]. It was administered once. I re‑evaluated him at [time]; vitals have been stable, exam unchanged, and labs [result summary if relevant]. I’ve discontinued the incorrect order, placed the correct one, and added [monitoring / labs]. I’ve also discussed with [senior/pharmacy].”

Short. Clear. Ownership + current status + plan.

B. Do you tell the patient/family?

If there was:

- Actual harm

- Potential for harm that required monitoring or intervention

- Change in management or prolonged stay likely related to the error

Then yes, this usually needs disclosure. Most hospitals have a policy on this and often prefer the attending or senior to lead that conversation with you present.

Your job:

- Raise it: “Do you want to speak with the patient/family about this with me there?”

- Be available to answer clinical questions during/after the conversation

- Learn how your institution does disclosure.

Do not freelance a big “I made a huge mistake” monologue without looping your attending in. Transparency is good; doing it in a way that creates confusion or legal risk is not.

Step 5: Document It Properly (Without Self‑Flagellation in the Note)

You need two kinds of documentation:

- Clinical documentation in the chart

- Internal reporting if required (safety event system)

A. What goes in the progress note

You document facts and your medical response. Not an emotional diary.

Example paragraph you can adapt:

“Overnight, an incorrect order for [drug/dose/route] was placed at [time] due to [brief description – e.g., selection of wrong order set]. The medication was [administered once / not administered]. On recognition at [time], the order was discontinued and the correct order for [drug/dose] was placed. Patient was assessed at bedside: [vitals], exam [summary]. Relevant labs: [list]. Plan includes [monitoring, labs, interventions]. Discussed with [senior/attending/pharmacy].”

You do not write: “I made a terrible mistake” or speculate on legal issues. Stick to clinical facts and your management.

B. Safety event reporting

If your hospital has an incident reporting system (it does), this may very well qualify. In many systems, the bar to report is low: any potential for harm, not just actual harm.

You:

- File a report with factual description, including time, drug, doses, what happened after

- Avoid blaming others (“nurse should have caught it”) even if there were system failures

- Be ready to discuss it in an M&M or QI setting later

This isn’t about punishment. It’s about patterns.

Step 6: Protect Yourself From Repeating the Same Mistake

Now the uncomfortable part: you have to look at why it happened. Not to beat yourself up, but to not be the person making the same error twice.

A. Do a 5‑minute debrief with yourself (and maybe your senior)

Right after things are stable, ask:

- Was I rushing? Distracted by another crisis?

- Did I rely too heavily on a pre‑built order set I barely read?

- Did fatigue or autopilot play a role?

- Did I prescribe something I wasn’t fully comfortable with?

Then tell your senior: “I want to make sure I don’t do this again. Can we quickly walk through what you’d do for [scenario]?”

Five minutes of targeted feedback is worth way more than 2 hours of abstract guilt.

B. Build small guardrails into your practice

Examples of practical guardrails:

- For high‑risk meds, say the dose out loud in your head and compare to typical range before signing: “Labetalol 10 mg IV, not 100 mg. Does that make sense?”

- Avoid ordering from default “favorites” for patients with unusual physiology (ESRD, cirrhosis, extreme age or weight)

- For look‑alike/sound‑alike meds (hydromorphone vs morphine, heparin vs insulin), double‑check both the drug and the concentration every time

- If you’re too tired to think straight, ask someone to sanity check high‑risk orders. Yes, even at 3 a.m.

Step 7: Know Which Errors You Absolutely Must Escalate

Not all order mistakes are equal. Some you handle mostly yourself with minimal ripple. Others need big escalation.

Here’s a rough triage guide:

| Scenario Type | Escalation Level |

|---|---|

| Wrong bowel regimen, no harm | Intern + day team only |

| One extra low-risk med dose | Intern + senior + note |

| High-risk med wrong dose (no harm) | Intern + senior + attending + report |

| High-risk med wrong dose (some harm) | Full team + event report + M&M likely |

| Event requiring reversal/ICU care | Full team + leadership + formal review |

When you’re unsure, assume it’s one level more serious than you think and loop people in.

A Few Real‑World Overnight Scenarios

Let’s run through some common categories you’ll actually face.

1. The missed critical test

You realize at 7 a.m. you never placed the midnight troponin or lactate you told the attending you’d trend.

What you do:

- Order it immediately and mark it STAT if still relevant

- Check the patient right now for any change

- In the morning, say: “I intended to trend troponins q6h but failed to place the midnight order; I ordered one at 7 a.m. and the patient remains stable with troponin [result].”

If the window mattered diagnostically (e.g., missed early rule‑out MI timing), discuss openly with your attending. This might change management (stress test timing, observation duration).

2. The anticoagulation screw‑up

You accidentally ordered therapeutic enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID on a patient who should have been on prophylactic 40 mg daily.

At 6 a.m. you see:

- They got one therapeutic dose at 11 p.m.

- No bleeding events, vitals stable, Hgb unchanged

Your sequence:

- Stop therapeutic dosing, restart prophylactic dose

- Evaluate patient for bleeding (neuro exam, stool, urine, skin)

- Repeat CBC if not already done

- Tell senior + attending, document, likely file a safety report

- Consider additional monitoring if they’re high bleed risk (elderly, recent surgery, etc.)

This is a “no sweep under rug” situation.

3. The wrong insulin dose

You ordered 20 units of rapid‑acting insulin instead of 2 units for a pre‑meal correction.

At 5 a.m. you realize it. The patient received it at 9 p.m.

- Check blood glucose now and review trend overnight

- If they had symptomatic or lab‑confirmed hypoglycemia, treat and document

- Adjust future insulin doses with more caution (and possibly pharmacist/endocrine input for complex regimens)

- Loop in senior/attending, document clearly

Again: own it, fix it, learn from it.

A Simple Mental Flowchart

When your stomach drops and you realize “That order was wrong,” run this chain quickly:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Realize order was wrong |

| Step 2 | Check if given or active |

| Step 3 | Assess patient and vitals |

| Step 4 | Stop or correct order |

| Step 5 | Call nurse, senior, maybe pharmacy |

| Step 6 | Notify day team, document |

| Step 7 | Order targeted labs/monitoring |

| Step 8 | Document and file safety report |

| Step 9 | High risk or harm? |

Keep that in your head. It simplifies the chaos.

Visual: What Residents Typically Do vs What They Should Do

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Panic & Hide | 20 |

| Quietly Fix Only | 35 |

| Tell Senior Late | 25 |

| Immediate Full Response | 20 |

Aim to be in that last category, consistently.

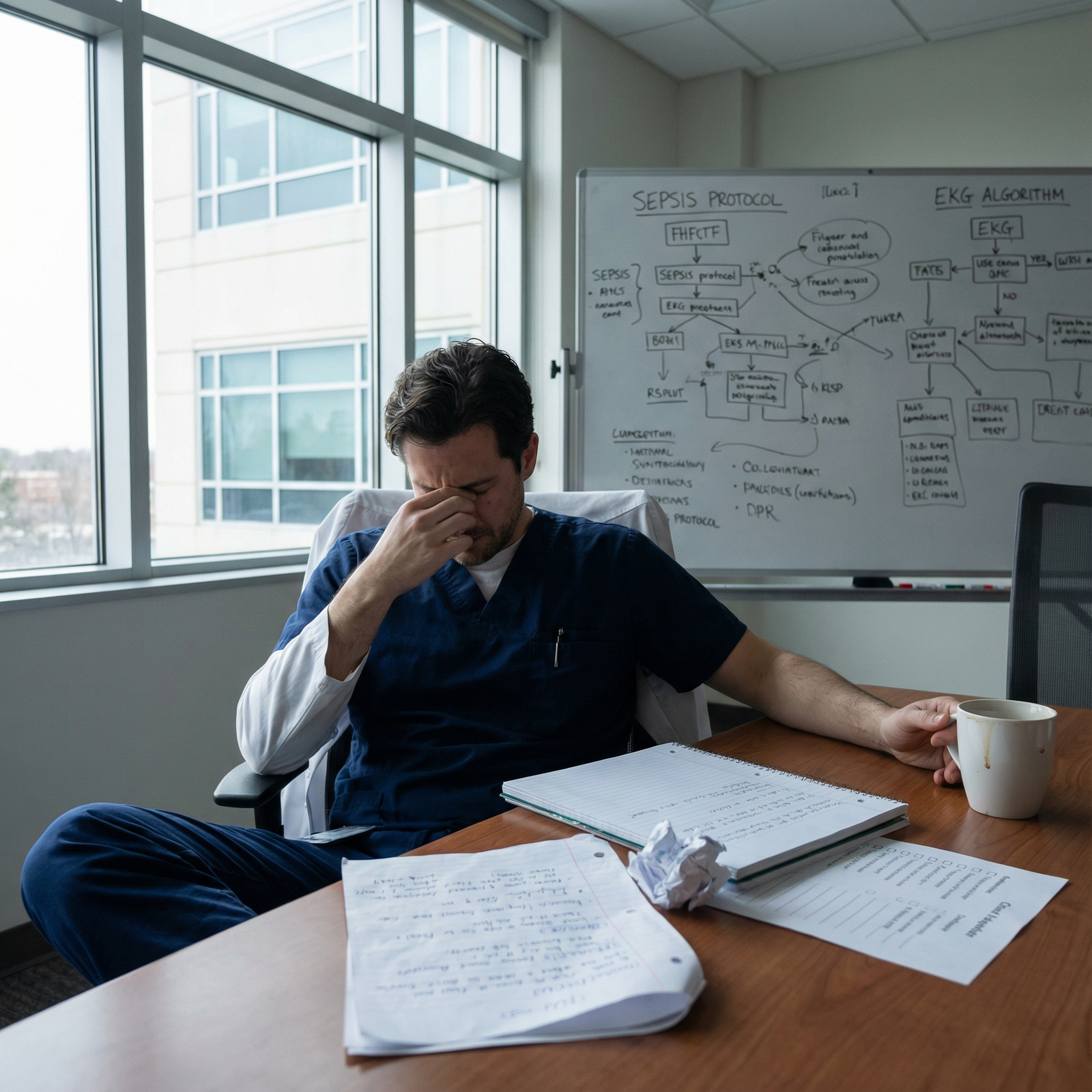

The Part No One Tells You: This Will Happen Again (In Some Form)

If you practice long enough, you will:

- Order the wrong thing

- Miss the right thing

- Realize it too late for total damage control at least once

Your goal is not zero mistakes. It’s zero unmanaged mistakes.

Attendings are not evaluating you on never screwing up. They’re watching:

- Do you catch your own errors?

- Do you communicate clearly?

- Do you put the patient first, even when it makes you look bad?

- Do you actually change your practice afterward?

Residents who handle errors well end up trusted. Residents who hide them don’t.

Quick Snapshot: Who to Call, When

| Situation | Minimum People to Notify |

|---|---|

| Low-risk, no harm | Day team only |

| High-risk med, no harm | Nurse + senior + day attending |

| Any actual or suspected harm | Nurse + senior + attending + report |

| ICU patient or unstable vitals | Nurse + ICU team + attending |

| Potential legal/ethical concern | Attending + risk/ethics if asked |

Tape your own version of that to your workstation if you have to.

FAQs

1. What if the nurse or day team seems angry or blames me?

Some people will react emotionally in the moment. That is not your problem to fix right then. Your job is to stay factual, own your part, and keep the focus on the patient. You can say, “I understand this is frustrating. I’m focused on making sure the patient is safe and this doesn’t happen again.” Then keep moving. If someone is chronically demeaning or abusive over errors, that’s a separate professionalism conversation to raise with your program leadership later.

2. Should I ever not write about the error in the note?

If the error reached the patient or changed management, it almost always belongs in the chart. You’re documenting the clinical reality, not writing a legal confession. The only time you might limit detail is around internal process discussions (like RCAs) that your hospital specifically wants outside the chart. When uncertain, ask your attending: “How would you like this documented?” But omitting significant events from the record is worse than uncomfortable documentation.

3. Will a single overnight error ruin my reputation or career?

No. What ruins reputations is repeated carelessness or concealment. Most attendings still remember their own worst intern mistakes with nauseating clarity. They’re comparing your response to how they handled theirs. If you caught it, fixed it, told the right people, and learned from it, you’re actually ahead of a lot of residents.

4. What if I realize the error days later, not the next morning?

Same algorithm, just with more humility. You still: confirm exactly what happened, assess the patient now, determine if late harm could have occurred, notify senior/attending, document, and file a report if indicated. You may have to explicitly say, “I should have caught this earlier. Here’s what I’m changing in my workflow so this doesn’t repeat.” Trying to bury it because time has passed is where people really get into trouble.

5. How do I keep from mentally spiraling after a serious mistake?

You treat your mental health with the same seriousness you treated the patient. Debrief with a trusted senior or attending. Use institutional support if there was real harm (many places have “second victim” resources, even if they use terrible branding for it). Limit the replaying-in-your-head loop to structured reflection: What happened? Why? What’s my concrete change? After that, you deliberately put it down. If you notice you can’t sleep, you avoid certain patients, or your anxiety spikes going into call, that’s not weakness; it’s a signal to get help early.

Open your last two on‑call notes right now and scan the medication sections. Find one high‑risk or complex order you placed half‑tired. Ask yourself: “If this had been wrong, would I know exactly what to do next?” If the answer is no, sketch your personal 6‑step response on a sticky note and stick it to your workstation before your next call.