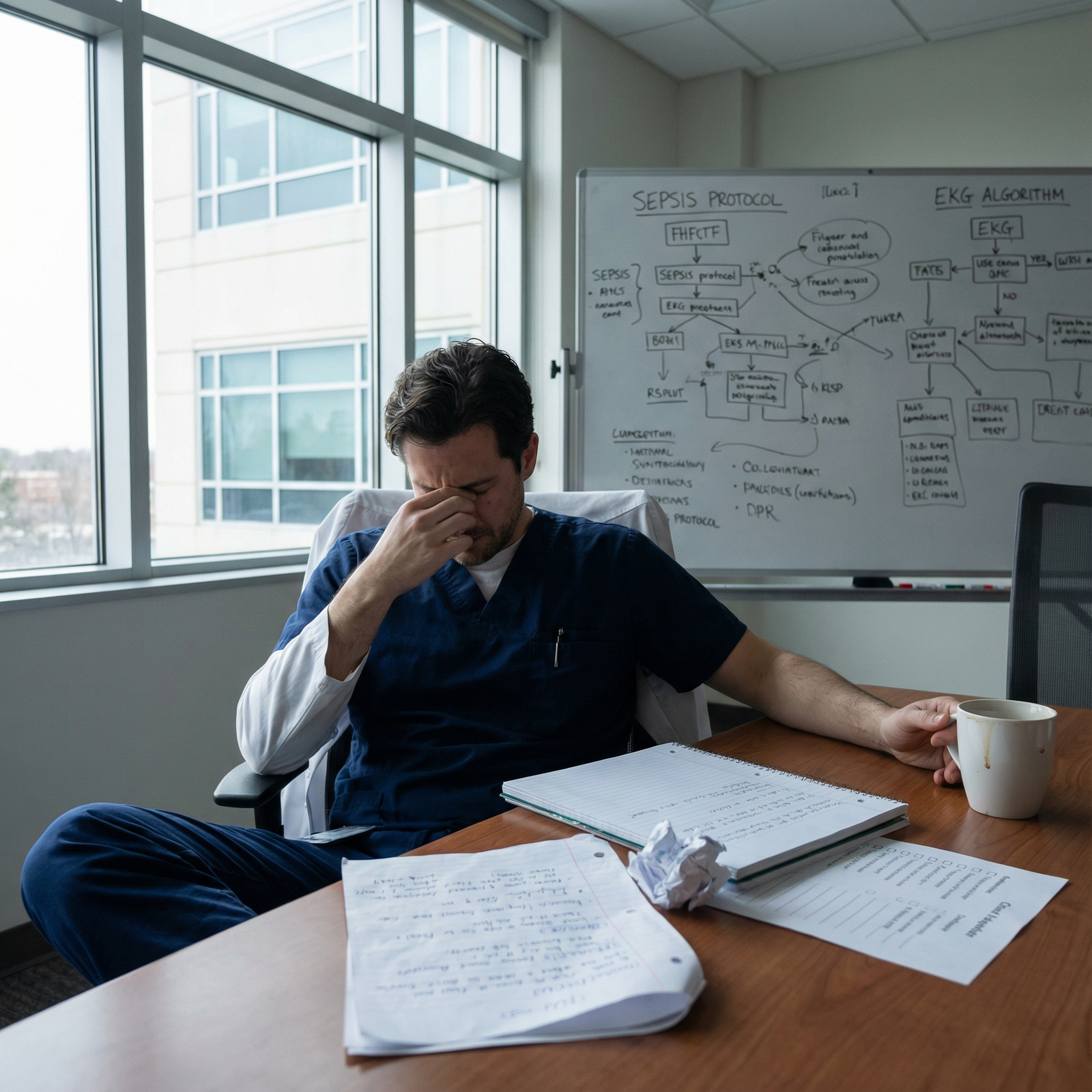

It’s 2:37 a.m.

You’re on night float, halfway through a lukewarm coffee, finishing a note you should’ve written three hours ago. The cross-cover pager explodes: three beeps at once. One is a new admission. One is a nurse about a patient not peeing for six hours. And the third is the one you silently dread:

“Can you call Dr. Patel about Mr. X – HR in 140s, BP 88/50.”

You stare at the number. You know this attending. Daytime she’s completely reasonable. Smart, fair, actually teaches. But at night? One misstep on a call and the temperature drops 20 degrees. The way she exhales before answering. The clipped “Okay, what’s the story?” that makes your brain empty.

You dial, heart rate now matching your patient’s.

Let me tell you what’s actually going on in her head. And why attendings get angry about overnight pages in ways no one really explains to you.

The Dirty Secret: Nights Expose Who Can Be Trusted

Nobody says this bluntly on orientation day, but every overnight call is basically a live trust assessment.

Attendings remember who they can sleep through the night with, and who guarantees a disaster at 6 a.m.

When we sit in those behind-closed-doors meetings and talk about residents, we do not start with “great fund of knowledge” or “excellent presentations.” We start with:

“Can I sleep when they’re on call?”

That’s the real metric.

Overnight, your pager use is shorthand for:

- Do you recognize sick vs not sick?

- Do you think before you call?

- Do you omit crucial data and make us pull it out of you?

- Do you call for nonsense?

- Or worse: do you not call when you should?

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Missing Key Data | 40 |

| Calling Too Late | 25 |

| Calling Too Often | 15 |

| No Plan Offered | 15 |

| Paging Wrong Person | 5 |

The anger you hear in their voice is almost never just about that page. It’s about a pattern they think they’re seeing, or think they’ve already seen from you or your program.

And here’s the real kicker: attendings on night call are not just triaging patients. They’re triaging their own legal risk, their sleep, and their already thin patience with a system that’s more broken than you realize as an intern.

Two archetypes you’ll meet

You’ll see two broad flavors of “angry” attendings at night:

The “I’ve been burned before” attending – the one who’s had a real miss: the undiscussed troponin, the “just a little short of breath” that coded at 4 a.m. Their anger is fear wearing armor.

The “this system is stupid and you’re part of it” attending – they’re mad at EMR alerts, impossible patient loads, admin creep, and insurance. Your 3 a.m. page becomes the tipping point.

You will misinterpret both of these as “they hate me.”

Most of the time, they don’t. They hate getting surprised.

What Attendings Think You Should Have Done Before Paging

Let’s pull the curtain back. Here’s the invisible checklist running in an attending’s head when they get your overnight call.

They will not say this out loud. But they all have some version of it.

1. “Why don’t you have basic vitals and context?”

If you call with:

“Hey, Mr. Jones doesn’t look good – the nurse is worried”

and then you don’t have last vitals, trend, mental status, oxygen needs, and whether you’ve physically seen the patient, you’ve already lost them.

They’re not mad that you called. They’re mad they now have to do what you should have done before picking up the phone.

They’re thinking:

“You walked into this conversation unarmed and now I have to build the whole picture from scratch while half-asleep.”

There’s a universal expectation: if you are rattling my phone awake, you’ve already:

- Looked at the chart

- Looked at the last set of vitals and labs

- Put eyes on the patient (for anything beyond a purely administrative question)

- Talked to the nurse for their impression

When you skip one of those, they feel set up to miss something.

2. “Where’s the damn differential?”

You say:

“Patient’s tachycardic to 140.”

They’re waiting for the next sentence.

They want:

“Tachy to 140, baseline 90s, septic earlier today, now febrile again to 39.5, low urine output, MAPs low 60s despite 2 liters. I’m worried he’s progressing to septic shock.”

What they actually get, too often, is:

“Yeah… I’m not sure why.”

Cue the annoyed tone.

They’re not angry at the tachycardia. They’re angry that you came to them without even a hypothesis. Even a wrong but sincere hypothesis is better than “no idea.” Because “no idea” sounds like “I didn’t think.”

Why Certain Types of Pages Light Their Fuse

Not all pages are equal. Some will always trigger an irritated response unless you handle them perfectly.

Let’s walk through the classics and what’s happening behind the scenes.

1. “FYI” pages at 3 a.m.

No attending wants a pure FYI at 3 a.m. unless it changes management right now.

You say: “Just FYI, the Hgb dropped from 9.0 to 8.0.”

They hear: “I woke you up for something that can be handled at 6 a.m. rounds.”

What they wished you had done:

- Ask: Is the patient hemodynamically stable? Any signs of bleeding? New symptoms?

- Decide: Can this safely wait? If yes, document, sign-out, and mention in the morning.

- If you do call, attach a plan: “I’m not asking to transfuse now; just letting you know we might need to repeat a CBC in the morning.”

The anger isn’t at being informed. It’s at being forced into a decision that didn’t need to happen at that hour.

2. “Can you put in this order?” pages

Here’s the one that really sets people off.

Nurse pages: “We need IV fluids for hypotension, can you call the attending for an order?”

You then call the attending to ask what fluid and rate.

This is where you get the icy: “What do you want to give?”

They’re mad because from their perspective, you’re outsourcing basic resident-level thinking. NS vs LR, 500 vs 1000 bolus – this is your lane. When you call without a proposal, they feel like a human order entry system.

A better call:

“Mr. X is 88/50, tachy 120, was 110/70 earlier. Likely hypovolemic from diarrhea; exam looks dry, lungs clear. I’d like to give 1 L LR bolus and reassess in 30 minutes. Any concern with that?”

Now they’re not angry. Now they’re collaborating.

3. “I didn’t see the patient yet” pages

This is the one that gets repeated in morning teaching like a cautionary tale.

If you call and the attending asks, “What does the patient look like right now?” and you answer, “I haven’t seen them yet, nurse just paged,” the conversation turns cold.

Because here’s what they’re thinking:

- “You woke me up before you even walked down the hall?”

- “You’re asking me to make a decision with less data than you could get in 60 seconds?”

Attendings will absolutely remember the resident who always eyeballs the patient before calling. The trust difference between those two residents is night and day.

What They’re Afraid Of But Won’t Say

Let’s talk fear. Because behind the anger, that’s what lives there.

1. Fear of the 7 a.m. surprise

The single worst moment for an attending is showing up at 7 a.m., learning some patient decompensated overnight, and hearing: “Yeah, I heard they weren’t doing great around 3 a.m.”

If they were never called, that’s when you see rage. Not annoyance. Rage.

From their chair, that’s career-ending territory. Consultants, quality reports, M&M. They will absolutely throw the resident under the bus if the chart shows: “Nurse paged resident for hypotension at 2:00, no reassessment documented, no page to attending noted.”

They do not want to be “the attending who slept while the patient died.”

So every time they hear you vaguely minimize a concerning sign (“they’re a little hypotensive but I think they’re OK”), their brain jumps to that scenario. That’s why their tone sharpens.

2. Fear that you don’t respect “near miss” stories

Most attendings over 40 have a story they replay at night. They won’t tell you the full version. What you get is the sanitized conference version.

The real one is darker:

- The resident who didn’t call about rising troponins because “he looked fine”

- The sepsis patient nobody escalated on because “he always runs a little low”

- The GI bleeder whose “slight dizziness” became a code

So when you sound casual about something they’ve seen end badly, they react strongly. It’s not you. It’s their ghosts.

| Page Type | Typical Attending Reaction | How to Upgrade It |

|---|---|---|

| Pure FYI lab change | Annoyance | Attach risk assessment + plan suggestion |

| “What do you want to do?” | Irritation | Offer your concrete recommendation first |

| No patient assessment yet | Anger / loss of trust | See the patient before calling |

| Late call on decomp | Real anger + documented fallout | Call early when trend is worsening |

| Borderline but thoughtful | Respect, even if they disagree | Shows judgment and initiative |

The Politics You Don’t See: Notes, Emails, and Your Reputation

Here’s what no one tells you during intern orientation: your overnight call style gets reported. Not in a formal way usually. In emails, quick hallway comments, and those “how’s the new class?” conversations.

I’ve sat in exactly those meetings.

Phrases you never want associated with your name:

- “They call for everything but never have a plan.”

- “I don’t sleep when they’re on – I don’t trust their filter.”

- “They minimize things that really worry me.”

Flip side, the good ones:

- “They call at the right times, and they’ve always thought it through.”

- “I’d let them run the unit with minimal backup.”

- “They don’t freak out, but they don’t sit on things either.”

Your overnight pages are the raw data those judgments are built from.

And when attendings get angry on the phone, half the time it’s not about you, it’s because they’ve had three bad experiences already that month and you just stepped onto the landmine.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Page from nurse |

| Step 2 | Look at vitals and chart |

| Step 3 | See patient |

| Step 4 | Call RRT or Code |

| Step 5 | Formulate plan and call attending |

| Step 6 | Place orders and document |

| Step 7 | Reassess patient after orders |

| Step 8 | Emergent instability |

| Step 9 | Needs attending input now |

How to Page in a Way That Rarely Triggers Anger

You cannot eliminate all annoyed responses. Some attendings are just miserable at night. But you can lower the odds dramatically.

Here’s what “attendings who’ve been doing this 20 years” quietly expect from a solid night-call resident.

1. Lead with “sick or not sick” and why

If you open with “I’m worried about this patient,” and then back it with data, they will immediately shift into serious mode and drop the attitude.

Example: “Hi Dr. Lee, sorry to wake you. I’m genuinely worried about Mr. Smith in 824. He’s more tachycardic, pressures are drifting down, and he looks noticeably more dyspneic than earlier.”

That is a very different start than:

“So, uh, Mr. Smith’s heart rate is up a bit…”

You’re signaling: “This is not noise. This is signal.”

2. Use the triad: Situation – Assessment – Plan

If you want to sound like someone who knows what they’re doing at 3 a.m., compress your call into this rhythm.

“Quick page about Ms. Jones in 612. She spiked a temp to 39.2, HR now 120, BP stable at 118/70 on 2L NC, satting 94%. On exam she’s more tachypneic, lungs with new crackles on the right base, no abdominal tenderness. I’m worried this could be worsening pneumonia vs volume overload. I’d like to get a stat CXR, draw repeat lactate and blood cultures, and give a 500 LR bolus and reassess. Are you okay with that or would you adjust?”

You framed:

- The situation

- Your assessment

- Your plan

Most attendings will not yell at that. They may tweak your orders. But you’ve shown judgment.

3. Know what must trigger a call

If you page for this stuff early, they rarely get angry. They get angry when they discover it later in the chart.

Things that nearly always warrant a night call:

- New or escalating oxygen requirement

- New pressor requirement or sustained MAP < 65 despite fluids

- New neuro change: confusion, focal deficit, altered LOC

- True chest pain or EKG changes

- Significantly low urine output with rising creatinine in a sick patient

- Safety issues: family threatening, elopement risk, restraints, major falls

You can still frame it well. But not calling at all is how people get truly angry in the morning.

What To Do After a Bad Call

You will screw this up at some point. Everyone does. You’ll have that call where the attending snaps, you hang up, stare at the phone, and feel both humiliated and furious.

Here’s what separates residents who grow from the ones who get quietly written off.

1. Don’t argue at 3 a.m.

You won’t win. They’re tired and irritated. You’re tired and defensive. That’s how regrettable quotes end up documented in the chart.

Stick to:

- Clear data

- Clarifying questions

- “Just to confirm, you’re okay with…”

If they’re unreasonably harsh, log it mentally. We’ll use that later.

2. Debrief – with someone who knows that attending

Talk to a senior or chief the next day. Not to whine. To calibrate.

“Last night I called Dr. X for [situation]. She got really upset that I didn’t [thing]. What would you have done? How does she like to be called?”

The best residents run these post-mortems and then adjust. That’s how you stop triggering the same landmines.

3. Occasionally, follow up with the attending

This is advanced, but powerful.

After a particularly rough interaction, catching them later and saying, “I wanted to ask how I could have handled that call better,” does two things:

- Signals maturity and teachability

- Gives them a chance to walk back some of their tone, if they have any insight at all

A lot of them know they’re snappy at 3 a.m. They feel guilty about it later. You giving them an opening helps both of you.

What You Need to Remember at 3 a.m.

Underneath the anger, the sighs, the “you should have known that” comments, this is what’s really true:

Most attendings would rather you call one extra time than one time too few.

They’d rather be annoyed than be blindsided.

They judge you far more on your pattern than on any single imperfect page.

So your job is not to be perfect. Your job is to show:

- You think before you dial

- You see the patient

- You understand sick vs not sick

- You bring a plan, not just a problem

- You escalate early when your gut says “this is bad”

Overnight calls are not just interruptions. They are how attendings decide who they’d trust with their own family member at 3 a.m.

Years from now, you won’t remember the exact wording of that one brutal phone call. You’ll remember that you learned how to think clearly in the dark, with a pager buzzing, and no one holding your hand. And that’s the skill that actually turns you into the physician you wanted to be when you started all this.

FAQ

1. How do I handle an attending who’s consistently rude or demeaning on overnight calls?

Document the medical decisions clearly, keep your side professional, and start collecting patterns. Then loop in your chief or program leadership with specific examples, not vibes. Some attendings genuinely don’t realize how they sound at 3 a.m. Others are bullies. You can’t fix either alone. Use the chain of command, but only once you have real, repeated episodes, not just “they were short with me once.”

2. Is it better to over-page or under-page as an intern?

Early on, slightly over-page, but with a plan every time. If you’re going to err, err on the side of safety. What attendings hate is not “too many calls,” it’s “too many useless calls” or “late calls when things are clearly bad.” If your pages are thoughtful and patient-focused, the volume matters less. As you gain experience, your threshold will naturally rise.

3. What if the nurse pressures me to call the attending when I don’t think it’s necessary?

That happens. A lot. See the patient yourself. Explain your reasoning to the nurse: “I saw him, vitals are stable, I’m going to order X and monitor Y, and I’ll call the attending if Z happens.” If the nurse still insists and the issue is safety-adjacent, you can call the attending but frame it: “Nursing is very concerned about X; from my assessment he looks stable currently, but I wanted to loop you in.” That way your judgment is clear.

4. How detailed should I be when presenting overnight changes on morning rounds?

More detailed than you think on the thinking part, not the minutiae. They don’t need a five-minute replay of every phone call. They do want: what changed clinically, what you thought was happening, what you did, and how the patient responded. The overnight story is your chance to show: “In the middle of the night, when it counted, I was actually the doctor.”