Failing a major systems exam right before Step 1 dedicated is not a “wake-up call.” It is a brick wall. And if you treat it like just another bad test, you’re going to slam into Step 1 the same way.

Let me be blunt: you cannot keep doing what you did for that systems block and just “work harder” in dedicated. That’s how students end up failing Step 1 or barely passing when they had every chance to course-correct.

If this is you—big systems exam fail, dedicated around the corner—here’s how to actually handle it.

1. First 48 Hours: Stop the Spiral and Get Real Data

You’re probably cycling through the greatest hits right now:

- “I’m not smart enough for this.”

- “Everyone else is fine. I’m the only one who’s behind.”

- “I’ll just grind harder during dedicated and fix it.”

That third one is the dangerous one.

The goal in the first 48 hours is not “feel better.” It’s to stop self-destruction long enough to collect real information.

Step 1: Contain the emotional damage (but don’t lie to yourself)

Give yourself one evening to be upset. Cry, vent to one friend, rant about the exam structure, complain about your professor who loves obscure vasculitides. Fine.

Then put a line in the sand: no more catastrophizing after that night. Every time your brain goes “I’m going to fail Step 1,” translate it to: “Something in my system is broken. I’m going to find it and fix it.”

You’re not doing toxic positivity. You’re doing damage control so you have the bandwidth to think.

Step 2: Get the specifics of the failure

You need more than “I failed cardio/renal” or “Borderline on neuro.” You need actual data.

Go after:

- The score breakdown by topic or organ system

- Any performance categories the school gives (e.g., “low performance in path/phys questions,” “weakness in integration”)

- Copies or screenshots of questions you remember getting wrong (write them down while they’re fresh)

- Faculty feedback if they offer review sessions

You cannot fix “I’m bad at cardio.” You can fix “I miss any question that mixes EKG + pharmacology + hemodynamics.”

If your school offers review with the course director: go. Even if you’re embarrassed. Especially if you’re embarrassed.

Here’s what you say in that meeting:

“I failed this exam and I’m heading into Step 1 dedicated soon. I need to understand whether this was:

- Knowledge gaps

- Poor exam technique

- Time management

- Or something else.

Can we go through my performance breakdown and a few representative questions to pinpoint what went wrong?”

You’re not there to argue your grade. You’re there to diagnose a process failure.

2. Diagnose the Actual Problem (Not the One in Your Head)

Everyone who fails a big systems exam blames “not knowing enough.” That’s rarely the full story.

Most of the time it’s a mix of 3–4 issues. You have to identify your mix.

Here are the common patterns I’ve seen over and over:

Pattern A: Content foundation is Swiss cheese

Clues:

- You blank on basic facts

- You miss straightforward “single-step” questions

- When reviewing, you think: “I literally never learned this” or “I forgot that even existed”

If this is you, Step 1 dedicated cannot be 100% questions from day one. You need targeted content reconstruction in weak systems and high-yield topics.

Pattern B: You know stuff, but cannot apply it under pressure

Clues:

- You understand questions perfectly after seeing the explanation

- On review you say, “I was between these two answers” constantly

- Your practice questions at home go okay, but formal exams tank

This is an exam skills problem:

- Reading too fast

- Anchoring on the first plausible diagnosis

- Not using all the clues in the stem

- Not re-checking the actual ask (“Which of the following is MOST likely associated with…?”)

This group often does fine on Anki and summary sheets but crashes on mixed, integrated vignettes.

Pattern C: Timing and panic

Clues:

- You regularly guess entire blocks at the end

- You spend 3+ minutes on single questions because you “almost have it”

- Your heart rate spikes in the exam room and you lose focus

Different problem. This is not solved by reading more First Aid. It’s solved by:

- Strict timed blocks

- Hard rules for when to mark-and-move

- Practicing under actual test-like pressure (quiet room, same break pattern, no phone)

Pattern D: Life and burnout wrecked your studying

Clues:

- Major personal crisis during the block (health, family, relationship)

- Chronic exhaustion, can’t focus for more than 20–30 minutes

- You’re not “bad at cardio.” You were barely functional all block

In this scenario, your Step 1 plan has to include actual recovery time and realistic volume. “I’ll just brute force 12-hour days” is fantasy.

Most students are a blend of these, but one dominates. Identify yours, write it down, and keep it visible. Every decision during dedicated should address that root cause.

3. Reset Your Dedicated Timeline (Yes, You Might Need to Shift)

You cannot pretend this exam didn’t happen. It is data you must incorporate into your Step 1 plan.

Question 1: Do you need to move your Step 1 date?

You should strongly consider pushing your exam if:

- You failed a major systems exam within 3–6 weeks of starting dedicated

- Your NBME baseline is significantly below passing (for Step 1 pass/fail era, I mean clearly below the passing cutoff, not “a few points”)

- You’re missing entire blocks of content (never really learned neuro, or you’re faking your way through pharm)

If your school locks your timeline or makes pushing hard, talk to your Dean of Students or academic support with a clear pitch:

“I failed [system exam] and my baseline assessment is [X]. I’m concerned that without additional time to repair these weaknesses, I’m at risk for failing Step 1.

Here’s what I’m proposing:

- 2–4 additional weeks focused on [specific deficits]

- Planned reassessment with [NBME/CBSSA/school exam]

I’m not trying to avoid the exam. I’m trying to take it safely and responsibly.”

Show you have a plan. Not just fear.

4. Rebuilding the Foundation While Still Aiming for Step 1

Now: how do you use dedicated when you’re coming off a fail?

Step 1 dedicated should shift from “maximum volume” to “targeted rehab + boards prep.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Targeted Content Rehab | 35 |

| Question Bank Practice | 40 |

| NBME/Assessment Review | 15 |

| Rest & Recovery | 10 |

For the first 2–3 weeks (longer if your date is far away) aim for something like that split.

A. Targeted content rehab

You do not re-watch every lecture you ever had. That’s how you burn time and still fail.

Instead, use a high-yield core plus targeted deep dives in your worst systems:

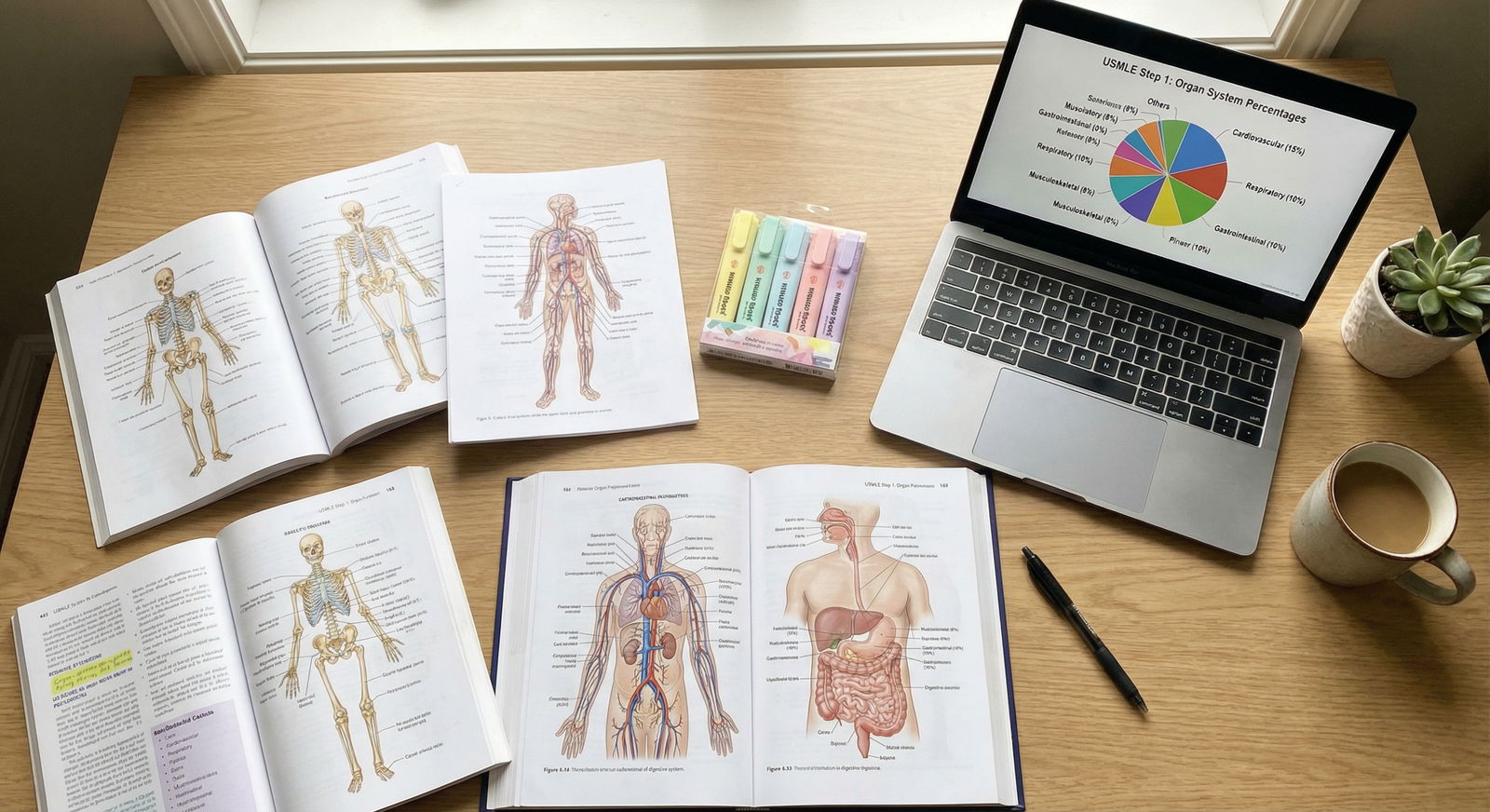

Core tools:

- Boards & Beyond / Pathoma / Sketchy (whatever your school and brain work best with)

- First Aid or equivalent Step 1 outline

- Light, targeted Anki (tag-based, not mindless reviews of 3,000 cards a day)

Where to focus:

- Systems you actually failed (e.g., cardio, renal, neuro)

- High-yield across-the-board topics:

- Cardio: murmurs, shock, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias

- Renal: acid-base, glomerular diseases, diuretics

- Neuro: localizing lesions, common neuropath, spinal cord lesions

- Pharm: autonomics, cardio drugs, antibiotics, psych

Pick 2–3 systems, not 8. Go deep enough that you can explain mechanisms out loud without notes.

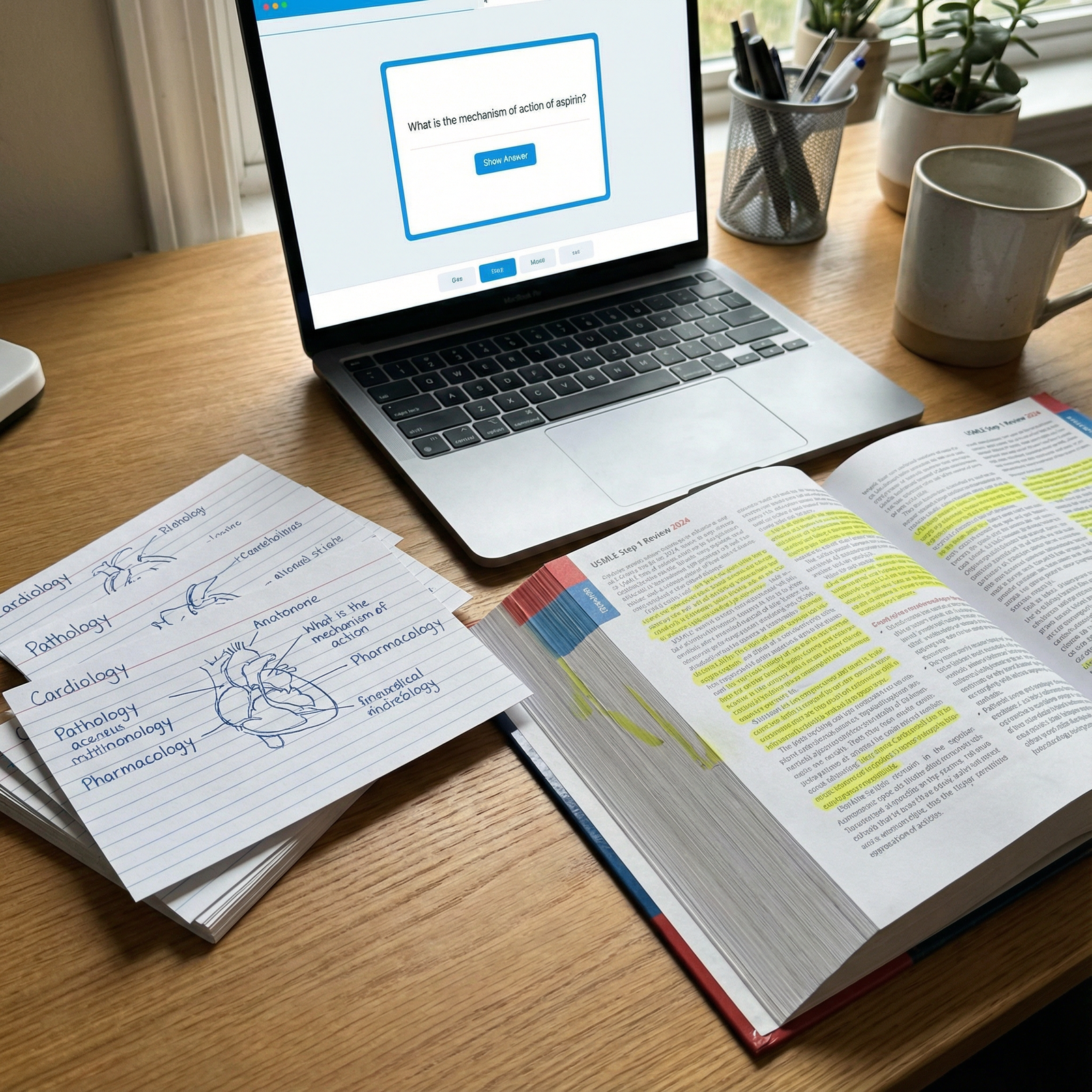

B. Question bank, but used correctly

You still need UWorld or Amboss or both. But your relationship with questions must change after a fail.

Wrong way:

“Let me hit 80–100 random questions a day, guess my way through, and skim explanations.”

Right way (while rebuilding):

- Start with system-based blocks in your weak areas

- Do them timed, but with lower daily volume (40–60 questions, especially at first)

- For every missed question, write down:

- What I thought was happening

- What I missed or misinterpreted

- What I will look for next time

If you failed cardio, your cardio QBank blocks should turn into a pattern-recognition boot camp. By day 7–10 you should start seeing the same classic patterns over and over and catching them early in the stem.

5. Fixing How You Take Tests, Not Just What You Know

This is the part almost everyone skips. And it is usually why the same students keep getting burned.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Read stem once |

| Step 2 | Identify key clues |

| Step 3 | State likely diagnosis or process |

| Step 4 | Re-read question ask |

| Step 5 | Eliminate wrong answers |

| Step 6 | Choose best match |

| Step 7 | Mark only if truly uncertain |

Here’s how to retrain your brain:

A. Force yourself to predict before looking at answers

On a missed question during review, ask:

- Did I commit to a diagnosis/pathophysiology before looking at choices?

- Or did I just float through and pick whatever seemed plausible?

If you’re not predicting, you’re vulnerable to distractors.

Practice saying in your head (or quietly to yourself if alone):

- “This is a restrictive cardiomyopathy vignette.”

- “This is nephritic, not nephrotic.”

- “They’re asking for the mechanism of the drug that fixes this.”

Then check choices. If your predicted idea isn’t there, that’s another issue: you mis-read or misunderstood the stem.

B. Slow down the first 10 questions of each block

Most students blow the first part of the exam because they’re wired with adrenaline. They read fast, they miss key modifiers, they misread “most likely” vs “least likely.”

Try this rule for every timed block:

- Questions 1–10: deliberately 10–20% slower than feels “natural”

- Force yourself to underline or mentally flag:

- Age, timing, and key risk factors

- What the question is actually asking in the final sentence

You can speed up later in the block when your brain is warmed up.

C. Train your “mark and move” muscle

If you failed your systems exam in part from timing, it’s because you think perseverance will magically produce insights if you stare long enough.

Bad habit. On Step 1, that costs you entire questions.

Set a hard rule in practice:

- If you’ve spent ~90 seconds and still feel genuinely lost:

- Eliminate obvious wrongs

- Pick between the finalists with your best reasoning

- Mark it

- Move on

You come back only if you have time at the end. This feels terrible at first. It’s the right move.

6. Integrate School Responsibilities Without Letting Them Sink You

You might not be in a clean “dedicated” period. Some schools cram in more material or remediation while you’re trying to prep for boards. Messy but common.

Here’s the rule: failing Step 1 is worse than scoring a few points lower on a school exam.

You still need to pass your courses, but the priority stack changes.

| Scenario | Priority |

|---|---|

| Upcoming school quiz, low stakes | Step 1 > Quiz |

| Cumulative systems final, high stakes | Final ≈ Step 1 |

| Remediation exam for failed block | Remediation > S1 |

| Light pass/fail small group assignment | Step 1 >> Group |

If you’re in remediation for the failed systems exam, here’s how to blend:

- Use your remediation content as your Step 1 foundation for that system

- Align resources: if they give you objectives, map them directly to B&B/Pathoma/UWorld topics

- Do not create two separate study universes (one “for school” and one “for Step 1”)

You want one integrated cardio plan, not School-Cardio vs Step1-Cardio.

7. Monitoring Progress: When Are You Actually Back on Track?

You will not feel like you’re ready for Step 1. That’s normal. So you need external markers.

Here’s a simple tracking structure:

| Category | NBME Score |

|---|---|

| Baseline | 52 |

| Week 2 | 60 |

| Week 4 | 66 |

| Week 6 | 72 |

Use something like:

- Baseline NBME or school comprehensive: even if ugly, you need a starting number

- Every 2 weeks: full-length NBME or half-length school practice exam

- Weekly: look at QBank performance by system and by discipline (e.g., pharm, path, phys)

You’re looking for:

- Weak systems: climbing toward or above passing range

- Fewer careless errors (misreading, missing “except,” etc.)

- Better timing: finishing blocks with at least 5 minutes to spare

If after ~3–4 weeks:

- Your weakest systems are still tanking

- NBME scores are flat or barely moving

- You still feel totally lost in vignettes

Then you re-open the “Should I push my exam?” conversation. That’s not failure. That’s damage control.

8. The Psychological Side: Disappointment Without Self-Sabotage

Let me be clear: failing a major exam sucks. It shakes your identity. Med students are used to being “the smart one.” This hits that directly.

You don’t have to pretend it’s fine. But you also don’t get to let it define the rest of your training.

What I’ve watched differentiate students who bounce back:

They stop using moral language about performance.

- Not “I’m dumb.”

- Instead: “My system for learning cardio was bad. I’m building a better one.”

They accept that shame is a terrible study partner.

If your inner monologue is “You’re behind, you’ll never catch up,” your brain will look for escape: TikTok, YouTube, random cleaning, doomscrolling. You call it “procrastination” but it’s avoidance of feeling like a failure.They put structure over motivation.

You will not “feel like” studying most of the time during this rebuild. You don’t wait. You build a schedule with blocks and you show up like it’s a clinical shift.

Simple daily skeleton during rebuild:

- Morning: 2–3 hours of targeted content (one system)

- Midday: 40–60 timed questions + deep review

- Late afternoon: lighter tasks (Anki, skim of First Aid pages, brief recap)

- Non-negotiable: 7 hours of sleep, some movement, at least one non-medical conversation with a human

That’s not “glamorous.” It works.

9. When to Get Outside Help (And What Kind)

If you’ve failed a big systems exam and:

- You also struggled repeatedly in pre-clinical courses

- You have a history of standardized test problems (SAT/ACT/MCAT barely scraping by)

- Or you find yourself rereading the same paragraph three times and nothing sticks

You might need more than “a better plan.”

Potential supports:

- School academic support: ask specifically for help with test-taking and pacing, not generic “study skills” lectures

- Learning specialist/psychologist: screening for ADHD, learning differences, or anxiety that explodes on exams

- Step 1 tutor or structured program: not mandatory, but useful if you truly don’t know how to build a plan or interpret your NBMEs

If you go the tutor route, be clear:

“I failed a major systems exam recently. I need help:

- Rebuilding this system

- Fixing how I approach questions

- Planning my dedicated timeline around this.”

If they start with “Just do more questions and you’ll be fine,” find someone else.

10. How to Walk Into Step 1 After a Recent Failure

You will remember that failed exam the morning of Step 1. That’s fine. It does not have to own you.

The night before:

- Review a concise sheet of your biggest “classic mistakes” (e.g., “Don’t ignore the age,” “Always check what they’re asking,” “Think: path → mechanism → answer”)

- Do not cram entire systems. You are not going to fix renal in one night.

- Set up your breaks, snacks, and logistics like you’ve practiced in your full-lengths.

Day of:

- Treat the first block as “warm-up,” not as the verdict on your existence.

- If you bomb a question, you say: “I’ll make it up later.” That’s it. No drama during the exam.

- Use that slow-down rule for the first 10 questions of each block. Every block, not just the first.

Yes, you failed a big exam. That is part of your story now. It does not have to be the headline.

Key Takeaways

- Failing a major systems exam before Step 1 is a system failure, not a character flaw. Diagnose the actual problem—content, test-taking, timing, or life burnout—and write it down.

- Dedicated after a fail must be rehab plus boards prep: targeted content rebuild in weak systems, disciplined question practice, and deliberate repair of bad exam habits.

- Track objective progress with NBMEs and system-specific performance. If the numbers don’t move, adjust the plan—or the exam date—before Step 1 becomes your next avoidable disaster.