No, burnout is not “just part of training.” It is a predictable, measurable systems failure that we’ve normalized because it’s cheaper and more convenient than fixing it.

Let me walk through what the data actually say, because the cultural narrative in medicine is badly out of sync with reality.

The Myth: Burnout as a Rite of Passage

You’ve heard all of this:

“Everyone’s exhausted. That’s residency.”

“If you’re not burned out, you’re not working hard enough.”

“It gets better after training. Just push through.”

This isn’t harmless locker-room talk. It’s a belief system that does three very specific kinds of damage:

- It reframes a pathological environment as a character test.

- It shifts responsibility from institutions to individuals.

- It treats serious risk (suicide, medical errors, career attrition) as a temporary inconvenience.

The punchline: none of this is backed by evidence. In fact, the data show burnout isn’t inevitable, isn’t evenly distributed, and doesn’t magically resolve with seniority.

What Burnout Actually Is (And Is Not)

First, definitions. Because people use “burnout” to mean everything from “I need a nap” to “I fantasize about driving off the highway on call.”

The most commonly used framework is from Maslach, and it’s not vague at all:

- Emotional exhaustion

- Depersonalization (cynicism, treating patients like objects)

- Reduced sense of personal accomplishment

This is not the same as:

- Being tired post-call.

- Feeling stressed during exams.

- Disliking one rotation.

Temporary stress is normal. Burnout is a sustained state that correlates with worse outcomes for you and your patients. That distinction matters.

The Data: Burnout Rates Are High, Variable, and System-Dependent

Let’s look at numbers instead of vibes.

Large U.S. studies of residents and medical students repeatedly show burnout rates in the 40–60% range. That’s not “some people had a rough month.” That’s epidemic-level dysfunction.

But here’s the part the “it’s just training” crowd ignores: those rates are not fixed. They change when systems change.

| Group | Burnout Prevalence (Approx.) |

|---|---|

| U.S. medical students | 45–55% |

| U.S. residents/fellows | 50–60% |

| Practicing physicians overall | 40–55% |

| Residents in high-support programs | 25–35% |

| General U.S. working population | 25–35% |

Are the residents in high-support programs magically more resilient? No. They have:

- Reasonable workload caps actually enforced

- Attending support and supervision

- Less chaotic scheduling

- Better staffing and fewer useless administrative tasks

Change the system; change the burnout rate. That alone kills the “burnout is just part of becoming a doctor” narrative.

If it were truly “just training,” you’d expect:

- Similar burnout levels across all specialties. Not true.

- Similar burnout levels across institutions with similar learners. Also not true.

- A consistent decline in burnout after training. Not really true either.

What you actually see: specialties with heavier clerical loads, chaotic workflows, and worse staffing have higher burnout. Programs with better culture and structure have lower burnout in the same specialty.

That points the finger where it belongs: at design, not destiny.

Burnout Is Not Just a Personal Problem — It’s a Safety Problem

Treating burnout as a private, emotional issue is convenient for institutions. It’s also wrong.

The evidence linking clinician burnout to patient care isn’t subtle:

- Higher burnout → more self-reported medical errors

- Higher burnout → worse patient satisfaction and communication scores

- Higher burnout → more safety events and near-misses

This isn’t about “you’ll be unhappy but the patients will be fine.” They’re not.

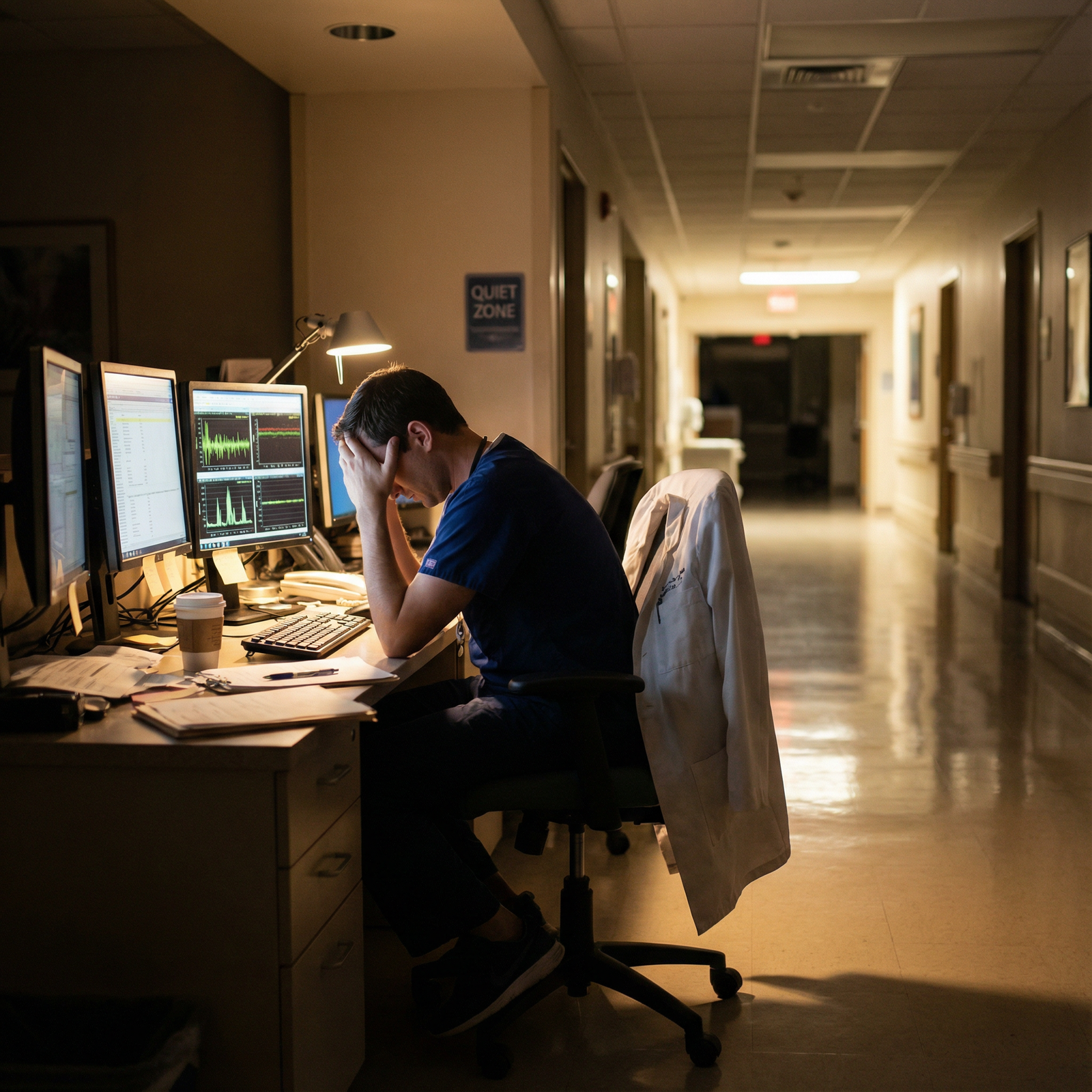

Think through a real-world scenario you’ve probably seen or lived:

- Night float resident admits five patients between 1 a.m. and 4 a.m.

- EMR tasks pile up, cross-cover pages keep coming, no chance for actual rest.

- That same resident, now cognitively fried, is expected to interpret subtle lab changes or EKGs at 6 a.m.

The risk here isn’t theoretical. Cognitive performance under chronic sleep deprivation and emotional exhaustion drops to the equivalent of working drunk. We would never say “being drunk is just part of training.” Yet we normalize the functional equivalent when it’s from exhaustion and burnout.

The Suicide and Mental Health Data: “Part of Training” Becomes Lethal

Now the part people like to gloss over with “dark humor.”

Medical trainees have:

- Elevated rates of depression and suicidal ideation vs. age-matched peers

- Shockingly low rates of seeking treatment, thanks to stigma and licensing questions

- Well-documented cases where “fine yesterday” residents die by suicide with no visible warning that anyone took seriously

Burnout isn’t the same as depression, but they frequently co-exist and interact. Pretending that severe burnout is just “toughing it out” is how programs sleep at night while trainees spiral.

If any other industry had this combination of:

- Extremely high stress

- Elevated suicide risk

- Documented reluctance to seek care because of job consequences

…we’d call it an ethical disaster, not a rite of passage.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| General Population | 8 |

| Medical Students | 15 |

| Residents | 20 |

Those numbers are approximate, but the direction is consistent across studies: higher risk in medicine, especially during training. Calling that “part of training” isn’t just wrong; it’s ethically grotesque.

Systems vs. Grit: Why “Resilience Training” Is Mostly a Fig Leaf

Another myth: “We just need more resilience workshops.”

Let me be blunt. Teaching mindfulness to someone working 80 hours a week, with poor staffing, chaos, and punitive culture, is like teaching breathing exercises to someone while you hold their head underwater.

Resilience skills can help. But only in environments that aren’t fundamentally abusive.

Here’s what the evidence does and does not support:

Individual-level interventions (mindfulness, CBT, coaching)

→ Small, short-term reductions in burnout scores. Effects often fade if the environment doesn’t change.System-level changes (work-hour reforms, better staffing, better scheduling, reducing pointless clerical work, supportive supervision)

→ Larger and more durable reductions in burnout and depression.

This is not mysterious. You’re not burned out because you failed a wellness seminar. You’re burned out because the demands of your work chronically exceed your ability to recover, and the system is designed to use your sense of duty as free labor.

Cross-Program Differences: Proof It’s Not Inevitable

If burnout were simply “what happens when you train,” changing hospitals shouldn’t matter much. Yet it does. A lot.

I’ve watched residents transfer from one large urban program to another and report:

- “I’m working fewer hours but learning more because the teaching is focused.”

- “The last place treated us like warm bodies. Here I’m treated like a learner.”

- “I still get tired, but I’m not constantly on the edge.”

Same specialty. Same general patient population. Completely different burnout trajectories.

What varied?

- The ratio of service to education

- Whether seniors and attendings protected teaching time

- Whether feedback was constructive or demeaning

- Whether schedule changes were done with any respect for trainees’ lives

You can’t look at that variation and honestly claim burnout is “just what training is.” It’s what badly designed training is.

The Ethical Problem: Normalizing Harm as Professionalism

Let’s talk ethics, since your prompt explicitly lives at that intersection.

The hidden curriculum in medicine tells you:

- Self-sacrifice is noble.

- Asking for help is weakness.

- Protecting your own sleep or mental health is selfish.

- Patients always come first, and “first” quietly expands to “only.”

On paper, we talk about nonmaleficence and beneficence. But when it comes to trainees, we suddenly decide harm is fine, as long as we call it “rigor.”

The ethical failures are layered:

Informed consent problem

Students sign up for long hours and hard work. They do not sign up for a culture that trivializes suicidality, punishes help-seeking, and frames basic human needs as lack of dedication.Double standard

We’d never endorse a treatment that degrades clinician functioning and increases patient risk, yet we endorse training structures that do exactly that.Blame shifting

By calling burnout “part of training,” institutions absolve themselves of responsibility. If you break under conditions that would break most humans, it’s recast as your personal failure.

An ethical training system does not rely on heroics and martyrdom as fuel. It relies on design.

What Actually Helps: Structural Levers That Change Outcomes

You can’t fix this alone, but you’re not powerless either. Some levers are squarely institutional; some are personal but targeted.

Structural changes with evidence behind them

Programs and institutions that take burnout seriously tend to do concrete, unsexy things:

- Enforce work-hour limits in reality, not just on paper.

- Build staffing that doesn’t assume residents are infinite free labor.

- Minimize unnecessary EMR clicks and non-clinical busywork.

- Provide confidential, non-punitive mental health care.

- Protect actual time off — not “you’re off but we might page you for results.”

When those elements shift, burnout rates shift. Again: not destiny. Design.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Training Environment |

| Step 2 | Workload and Hours |

| Step 3 | Culture and Supervision |

| Step 4 | Administrative Burden |

| Step 5 | Mental Health Support |

| Step 6 | Burnout Risk |

| Step 7 | Patient Safety |

| Step 8 | Physician Retention |

Individual actions that aren’t just “be more resilient”

You can’t wellness your way out of a toxic system. But you can refuse to internalize its lies.

Concrete moves that actually matter:

- Treat your basic physiologic needs as non-negotiable, not optional luxuries. Sleep, food, healthcare.

- Document unsafe practices and patterns; this is not whining, it’s data.

- Use whatever channels exist (GME committees, anonymous reporting, resident councils) to push for specific, measurable changes.

- Stop romanticizing overwork. “I haven’t peed in 12 hours” is not a flex; it’s a systems failure.

- Seek real mental health care early, not as a last resort when you’re actively planning to quit or worse.

None of this makes you weak. It makes you someone who refuses to let a broken system define what “professional” means.

The Long View: Burnout Does Not Magically Vanish After Training

The final piece of the myth is that burnout is a “training problem” that evaporates when you graduate. The data say otherwise.

Practicing physicians also have high burnout rates. In some fields, worse than residents.

Why? Because the same underlying issues carry forward:

- EMR overload

- RVU and productivity pressure

- Administrative nonsense

- Poor staffing

- Loss of control over schedule and patient panel

What sometimes improves after training is autonomy. You may gain:

- Slightly more control over how you practice

- The ability to change jobs or settings more easily

- More leverage to say no

But if you’ve been trained to believe that martyrdom is the baseline, you’re more likely to replicate that pattern in attending life—just with more money and less sleep debt buffer.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| MS3 | 40 |

| Intern | 60 |

| PGY2-3 | 55 |

| Early Attending | 50 |

The line doesn’t drop to zero after graduation. It flattens, if you’re lucky.

The Bottom Line: Stop Calling Pathology “Part of Training”

Let me strip this down to the essentials.

Burnout in training is common but not inevitable. Rates vary massively by program and system design. That alone disproves the “it’s just part of training” myth.

Burnout is not just about your feelings. It’s tied to increased medical errors, worse patient outcomes, higher depression and suicide risk, and long-term workforce attrition. Treating it as a rite of passage is ethically indefensible.

“Resilience” without structural change is a distraction. Real solutions involve workload, staffing, culture, and support — the unglamorous, expensive parts institutions often dodge.

You are not weak for struggling in a system that’s documented to break people. The myth that burnout is “just part of training” doesn’t make you tougher. It just lets bad systems off the hook.