You are here

It is 11:47 p.m. You have your ERAS personal statement draft open for the fifteenth time. The content feels “fine” — you have the childhood story, the big clinical moment, the line about being “honored to join your program.” Your mentor said it “reads well.”

And yet.

Something about it feels off. A little self-congratulatory. A little… stiff. You cannot quite tell if it sounds confident or arrogant, passionate or performative. And you know this: one wrong tone choice in a 700–800 word statement can brand you in the reviewer’s mind before they ever look at your letters or experiences.

Let me be very direct: entitlement in personal statements is almost never about what you claim to value. It is about the micro-signals in tone, word choice, and framing that scream:

- “I deserve this more than others.”

- “You should be lucky to have me.”

- “Obstacles are for other people.”

Faculty spot those signals in seconds. Residents spot them faster.

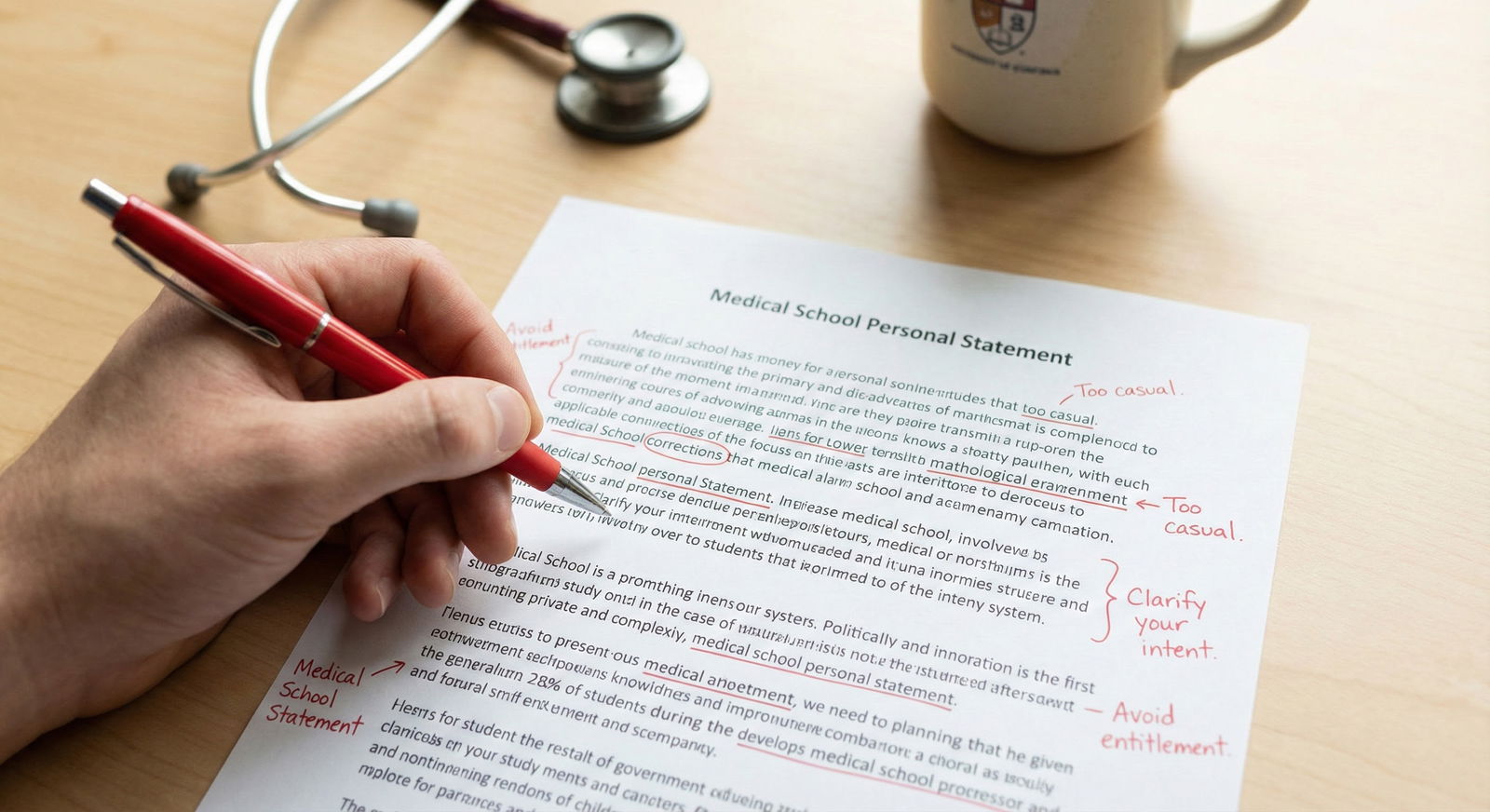

Let me break down the subtle, specific tone mistakes that quietly say “entitled,” even when you think you are just being honest or confident.

1. The “I’m the Exception” Narrative

This one shows up constantly, especially in otherwise strong candidates.

The structure is usually: “Unlike other applicants, I…” followed by something you assume makes you uniquely special. The problem is not that you are proud of your strengths. The problem is how you place yourself relative to everyone else.

Common phrasings that signal this:

- “Unlike many of my peers, I have always known I wanted to do [specialty].”

- “While others struggled to adapt during clerkships, I thrived.”

- “Where many students see [undesirable task] as a burden, I gladly embraced it.”

- “Most patients I encounter are surprised by my level of compassion and maturity.”

You are probably trying to say: “I am really committed / I work hard / I actually like this work.”

What the reader hears: “Other students are less committed, less adaptable, and less mature than I am.”

Program directors are not idiots. They know not every student is solid. But they also do not want the person who narrates their growth by stepping on everyone else.

Fix the structure, not the truth

Keep the content. Kill the comparison.

Bad:

“Unlike my classmates, I sought extra time in the ICU after my rotation ended.”

Better:

“After my ICU rotation ended, I asked to spend additional time on the unit to follow patients longitudinally and deepen my comfort with critical care.”

Same behavior. No imaginary pile of less dedicated classmates for you to stand on.

Bad:

“While many students avoid night calls, I volunteered for as many as I could handle.”

Better:

“I came to value overnight call for the autonomy and focused learning it provided, and I regularly signed up when additional coverage was needed.”

You can show above-average commitment without explicitly or implicitly trashing your peers. If your sentence only sounds strong because others look weak, the tone is off.

2. Inflated Language About Routine Experiences

Another entitlement red flag: describing standard medical student experiences as if they are heroic, unique, or groundbreaking.

You may not realize how often this happens. Think about these lines:

- “I led a multidisciplinary care team in managing a complex ICU patient.”

- “My research on a small retrospective dataset will revolutionize care for patients with X.”

- “I was the primary provider for a challenging clinic panel.”

- “My dedication to my patients is unparalleled.”

Be honest: as a medical student, you did not “lead” the team. You were not the primary provider. You joined a team, contributed as a learner, and followed supervision. When you oversell the role, you sound out of touch.

Faculty read this and think:

“If you are already calling that ‘leading’ as an MS3, what are you going to label your role as an intern?”

The “role inflation” check

Take any action statement and ask: Would everyone on the team agree with that description?

If the attending, resident, and nurse would raise an eyebrow, tone it down.

Inflated:

“I led the code team in resuscitating a patient with PEA arrest.”

Accurate, still strong:

“During a PEA arrest, I performed chest compressions and communicated rhythm changes, seeing firsthand how coordinated teamwork can restore circulation.”

Inflated:

“As the primary decision-maker in my research project…”

Accurate:

“I designed the data collection protocol, coordinated IRB submission, and worked closely with my mentor to refine our analytic plan.”

You do not need exaggerated verbs to sound capable. Precision is far more impressive than hype.

3. The Hidden “I Deserve It” Vocabulary

Certain words and phrases are saturated with entitlement energy, even when you mean well. They usually cluster around three ideas:

- What you are owed

- What you expect

- How others should see you

Watch for these clusters.

Entitlement cluster 1: “Deserve / Earned / Owed”

Examples:

- “I have worked hard and deserve a spot in your residency.”

- “My experiences have earned me the opportunity to train at a top-tier program.”

- “Given my dedication, I have earned the chance to pursue [competitive specialty].”

You may feel that way. Some of you have absolutely clawed your way to this point. But programs are not interested in what you think you are owed. They are interested in: Are you a good fit, safe to train, and not going to blow up the call schedule?

Reframe from “owed” to “ready to contribute.”

Bad:

“I have earned the right to train at a high-caliber academic program.”

Better:

“My background in clinical research and teaching has prepared me to contribute meaningfully in a rigorous academic program.”

Entitlement cluster 2: “Expect / Should / Naturally”

Examples:

- “I expect to match at a program that values research as much as I do.”

- “I should have the opportunity to care for the sickest patients.”

- “Naturally, I am looking for a program that recognizes my leadership potential.”

Reframe expectations as preferences and fit, not demands.

Bad:

“I expect a program that will provide me with extensive operative autonomy from day one.”

Better:

“I am seeking a program that prioritizes graduated operative autonomy and early hands-on experience, supported by strong supervision.”

Entitlement cluster 3: “Gifted / Exceptional / Stand out”

You do not need to label yourself as exceptional. Let the specifics show it.

Bad:

“My exceptional communication skills set me apart from my peers.”

Better:

“Families often asked me to return to the bedside to re-explain updates, feedback that reinforced for me the impact of clear, patient-centered communication.”

Same trait, very different tone. One is you declaring how special you are. The other is you describing concrete feedback and letting the reader draw their own conclusion.

4. The “Program as a Prize” Framing

This one is subtle and very common. You talk about your target programs like trophies to be won, not ecosystems you are joining.

It sounds like:

- “I am excited to match at a prestigious program like yours.”

- “Your renowned institution will provide the platform I need to achieve my goals.”

- “I aim to train at a top-tier program with an impressive name and national reputation.”

The problem is not that you care about program quality. Everyone does. The problem is centering the program’s reputation as an accessory to your ambitions, instead of showing how you will fit and contribute.

Faculty read:

“You are a stepping stone for my career and branding.”

Flip the direction of benefit

Entitled framing:

“Training at a prestigious academic center will position me for a future in competitive fellowships and national leadership.”

Balanced framing:

“I am drawn to academic centers that serve complex, diverse patient populations, where I can contribute to both patient care and resident education while preparing for potential fellowship training.”

You can still mention prestige, complexity, fellowship pipelines. Just do not make the program sound like a prize you think you are close to winning.

If your entire “why this specialty” paragraph feels like: “I want the sickest patients, the most complex cases, the best name brand,” you are broadcasting “I want the experience, not the grind that comes with it.”

5. Overconfident Future-Casting

A certain amount of ambition is fine. Expected, even. The problem starts when your future visions sound guaranteed, linear, and self-centered.

You have seen this:

- “I will become a national leader in cardiology.”

- “I plan to be a program director at a major academic center.”

- “I intend to transform the field of neurosurgery through groundbreaking research.”

- “In the near future, I will be running my own global health NGO.”

On their own, these are not evil. But strung together in a 4th-year personal statement? It reads as naive at best and entitled at worst. You have not done an intern year yet, and you are already planning how you will remake the discipline.

Programs are looking for residents, not prophets.

Ground ambition in current behavior, not fantasy

Bad:

“I will undoubtedly become a leader in orthopedic surgery.”

Better:

“I am energized by opportunities to lead. Co-chairing our student-run ortho interest group and organizing skills workshops has shown me how much I enjoy building educational spaces, and I hope to carry that forward in residency and beyond.”

See the pattern: show what you already do that points in that direction. Then express interest or hope for future roles. Not guarantees.

If your statement reads like a 10-year plan drafted by someone who has not done a month of night float, you lose credibility.

6. The “I Alone” Hero Story

You probably have a big patient story. Most people do. The problem is when that anecdote becomes a hero monologue.

The anatomy of an entitled hero story:

- You notice a problem no one else sees.

- You single-handedly fix it.

- The patient/family is transformed.

- The team recognizes your unique value.

That is not how medicine works. And everyone on the selection committee knows it.

Red-flag phrases:

- “No one else had taken the time to…”

- “Until I stepped in, the patient felt unheard.”

- “Despite the busy team, I was the only one who…”

- “Thanks to my diligence, the error was caught.”

Do you see the pattern? You are not describing your contribution. You are indicting the entire team to elevate yourself.

Re-center the team, keep your agency

Hero version:

“No one had explained the diagnosis in a way the patient could understand. I sat with her for thirty minutes and for the first time, she felt heard.”

Grounded version:

“Our team had explained the diagnosis several times, but the patient still seemed overwhelmed. One afternoon, I asked if I could sit and go through her questions slowly. As we talked, she began to articulate her fears more clearly, and I realized how much even a brief, focused conversation can ease anxiety.”

In the second version, you still act. You still matter. But you are not throwing the rest of the team under the bus.

If your patient stories consistently position you as the lone enlightened one in a sea of indifferent clinicians, you sound entitled, not compassionate.

7. Minimizing Privilege and Overdramatizing Hardship

Another place entitlement leaks through is how you talk about your background.

Two opposite mistakes:

- Pretending your advantages do not exist.

- Inflating minor inconveniences into hardship narratives.

Mistake 1 sounds like:

- “I built my career from nothing,” when your parents are both physicians.

- “Coming from a completely non-medical background,” when half your extended family is in healthcare but not MDs.

- “First in my family to pursue higher education,” when your siblings/uncles have advanced degrees.

Selection committees do not resent privilege. They resent dishonesty or deliberate blindness to it.

If you grew up in a physician household and had early exposure, say that plainly. Then show what you did with it.

Mistake 2 is the “struggle cosplay” problem:

- Calling a demanding research lab schedule your “greatest hardship.”

- Treating a single poor exam performance as a life-altering obstacle.

- Writing about “overcoming adversity” when what you really mean is “adjusting to a normal learning curve.”

An attending once said in a selection meeting I sat in on: “If that is the hardest thing that has ever happened to them, I am worried about how they will handle their first real complication.”

You do not need trauma to become a good physician. But if you label every bump as adversity, it reads as sheltered and self-centered.

How to acknowledge context without theatrics

If you had major challenges — immigration, financial strain, illness, discrimination — you can mention them. Just keep the focus on response, not self-pity.

If you had a smoother path, do not contort it into tragedy. Own it:

“I was fortunate to train in well-resourced institutions with strong mentorship. That support has shaped my commitment to teaching and to advocating for students who do not have the same access.”

That is humility. Not performance.

8. Tone-Deaf Specialty Talk (“I’m Above the Scut”)

Some entitlement is specialty-specific. Certain phrases instantly raise hackles in certain departments. I have seen these sink otherwise competitive applications.

Surgery:

- “I am eager to be in the OR as much as possible, rather than spending my time on floor work.”

- “I hope to focus on complex cases rather than routine bread-and-butter surgery.”

- “I am drawn to the acuity of trauma and critical care, rather than the more mundane aspects of general surgery.”

Internal Medicine:

- “I am most interested in the intellectually challenging cases rather than routine chronic disease management.”

- “I hope to work primarily in tertiary care centers rather than community hospitals.”

- “I enjoy ‘zebra’ diagnoses and find more common conditions less engaging.”

Family Medicine / Primary Care:

- “I intend to use primary care as a foundation for a subspecialty career.”

- “Ultimately, I see myself leaving direct patient care to focus on health policy / administration.”

- “I prefer outpatient work because it is more predictable and less intense than inpatient medicine.”

Emergency Medicine:

- “I enjoy the fast pace and exciting cases, and prefer not to have long-term follow-up.”

- “I like EM because I can stabilize patients and then pass them on.”

- “I am drawn to procedures rather than paperwork.”

The linking theme: you act like you are “above” the unglamorous but essential work.

Residency is largely unglamorous work. If your statement hints that floor work, chronic disease, clinic, paperwork, or continuity are beneath you, programs will assume you will be miserable. Or worse, toxic.

Reframe interest without trashing the rest

You can still state preferences.

Bad:

“I am excited by the OR and hope to minimize time spent on floor work.”

Better:

“While I am particularly energized by time in the OR, my sub-internship also taught me how crucial meticulous floor management is to surgical outcomes and team function.”

You are not expected to love every aspect equally. But you are expected to respect all of it.

9. Subtle Disrespect Toward Other Fields or Career Paths

Another entitlement marker: boosting your specialty (or your choice of it) by disparaging others who chose differently.

You see lines like:

- “I initially considered other specialties, but found them too limited / narrow / algorithmic.”

- “I chose [specialty] because I wanted more challenge than what I experienced in [other field].”

- “Other specialties did not offer the same level of excitement and impact.”

This may feel harmless. To a review committee that includes faculty from medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry, EM, surgery, and more, it sounds ignorant.

Similarly, lines that subtly mock those who do not want academic careers:

- “I could not see myself in a purely clinical community practice.”

- “I want to do more than just see patients in a clinic.”

- “I am not content with the limited scope of non-academic practice.”

You probably mean, “I want teaching and research in my career.” But you are implying that the vast majority of physicians — who practice in non-academic settings — are doing something lesser.

Better:

“I am drawn to academic practice where I can combine patient care with teaching and clinical research.”

That sentence tells me what you want, without insulting everyone else.

10. The “Thank You for Choosing Me in Advance” Ending

Let us talk about closings. A surprising number of personal statements end with something like:

- “I am confident I will be an excellent resident in your program.”

- “I know I will be a valuable asset to your residency.”

- “I look forward to the opportunity to join your program next year.”

You do not know that. Neither do they.

The tone problem is not confidence. It is presumption. You are writing as if the outcome is settled or obvious.

Instead, end with humility plus clarity about what you bring.

Presumptive:

“I am certain that I will excel in your residency and become one of your strongest residents.”

Grounded:

“I look forward to the intensity and responsibility of residency training and am eager to bring my work ethic, curiosity, and team-first mindset to my future program.”

You can swap “future program” for “your program” if you insist, but keep the verbs modest. “Hope to,” “am eager to,” “look forward to contributing” — those work. “Will absolutely,” “certain I will,” “know I will be” — those do not.

11. How Committees Actually React to Entitled Tone

You might be thinking: “Are people really that sensitive to a few words?” Yes. Because they are not just reading your words. They are extrapolating your 3 a.m. personality.

Here is how it plays out behind closed doors.

You have an otherwise competitive app. Above-average Step 2. Solid clerkship comments. Decent research. Then someone on the committee says:

- “The statement was a little ‘me, me, me.’”

- “Got some arrogance vibes.”

- “Seems like they think they are already a fellow.”

- “Reads as if they are doing us a favor by applying.”

No one will say, “Let us reject them solely because of tone.” But when they are deciding whom to rank higher, or whom to interview when they are one spot over their threshold, this matters.

Entitled tone does not usually sink you outright. It just moves you from “must interview” to “maybe.” From “our people” to “we have safer choices.”

12. A Quick Self-Audit for Entitlement Tone

Use this as a final pass checklist. Read your statement once, only looking for these things:

Any sentence that includes: “unlike,” “while others,” “many of my peers,” “most students.”

- Ask: Am I elevating myself by diminishing others?

Any self-label: “exceptional,” “gifted,” “natural leader,” “uniquely suited.”

- Ask: Can I replace this with a concrete example instead?

Any “deserve / earned / should / expect / will undoubtedly.”

- Ask: Can I rephrase as readiness, interest, or preparation?

Any patient story where you are the only competent or caring person.

- Ask: Can I recognize the team while still showing my role?

Any language trashing other specialties, non-academic careers, or routine work.

- Ask: Can I state my preferences without implying superiority?

Any overconfident future prediction.

- Ask: Can I swap certainty for “hope,” “aim,” or “plan,” tied to current behavior?

If you clean up those six buckets, you have already removed 80–90% of the entitlement signals I see every year.

Quick Comparison: Confident vs. Entitled Phrases

| Theme | Entitled Tone Example | Confident / Grounded Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Effort & readiness | “I deserve a spot in your program.” | “I feel prepared to contribute as a dedicated resident.” |

| Comparing to peers | “Unlike many of my peers, I sought extra responsibility.” | “I actively sought extra responsibility on my rotations.” |

| Future goals | “I will undoubtedly be a leader in this field.” | “I hope to grow into leadership roles over my career.” |

| Role description | “I led the team managing this complex patient.” | “I contributed to the team caring for this complex patient.” |

| Program fit | “I expect a top-tier program that matches my caliber.” | “I am seeking a program with strong teaching and research.” |

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Comparing self to peers | 25 |

| Inflating roles/experiences | 20 |

| Overconfident future claims | 20 |

| Program-as-prize framing | 15 |

| Minimizing team/others | 20 |

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Draft complete |

| Step 2 | Remove comparisons |

| Step 3 | Rephrase as readiness/fit |

| Step 4 | Anchor in team and actual responsibilities |

| Step 5 | Ground in current behavior + modest goals |

| Step 6 | Tone check with trusted reader |

| Step 7 | Any unlike others or many of my peers? |

| Step 8 | Any deserve/earned/expect? |

| Step 9 | Inflated roles or hero stories? |

| Step 10 | Overconfident future claims? |

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No tone issues | 60 |

| Mild entitlement cues | 20 |

| Moderate entitlement cues | 15 |

| Strong entitlement cues | 5 |

The bottom line

Three points, and you are done:

Entitlement in personal statements is almost never one big obvious mistake. It is the accumulation of small choices — comparisons to peers, inflated roles, presumptive language — that add up to “this person might be hard to train.”

You can keep your real achievements and ambition. The fix is in how you frame them: precise about your role, respectful of others, and grounded in what you have actually done rather than what you think you deserve.

Before you hit submit, do a ruthless tone pass. Strip out “I’m the exception” narratives, hero stories, “I deserve” vocabulary, and any hint that routine clinical work or non-academic careers are beneath you. Confidence is attractive. Entitlement is not.