You are here

It is 10:47 p.m. two days after your residency interview at a program that is actually on your realistic top-3 list.

You are re-reading your notes:

“Talked R01 on sepsis biomarkers w/ Dr. Patel – asked about my QI poster, mentioned their multi-center trial starting next summer.”

You want to send a follow-up email that does two things:

- reminds them exactly who you are, and

- signals that you are serious about their research environment.

What you do not want: sounding like a try-hard, misquoting the faculty member, or turning a polite thank-you into a dense research abstract no one will read.

Let me walk you through how to reference those research conversations in a way that actually helps you, rather than blends into the generic “Thank you for your time” noise.

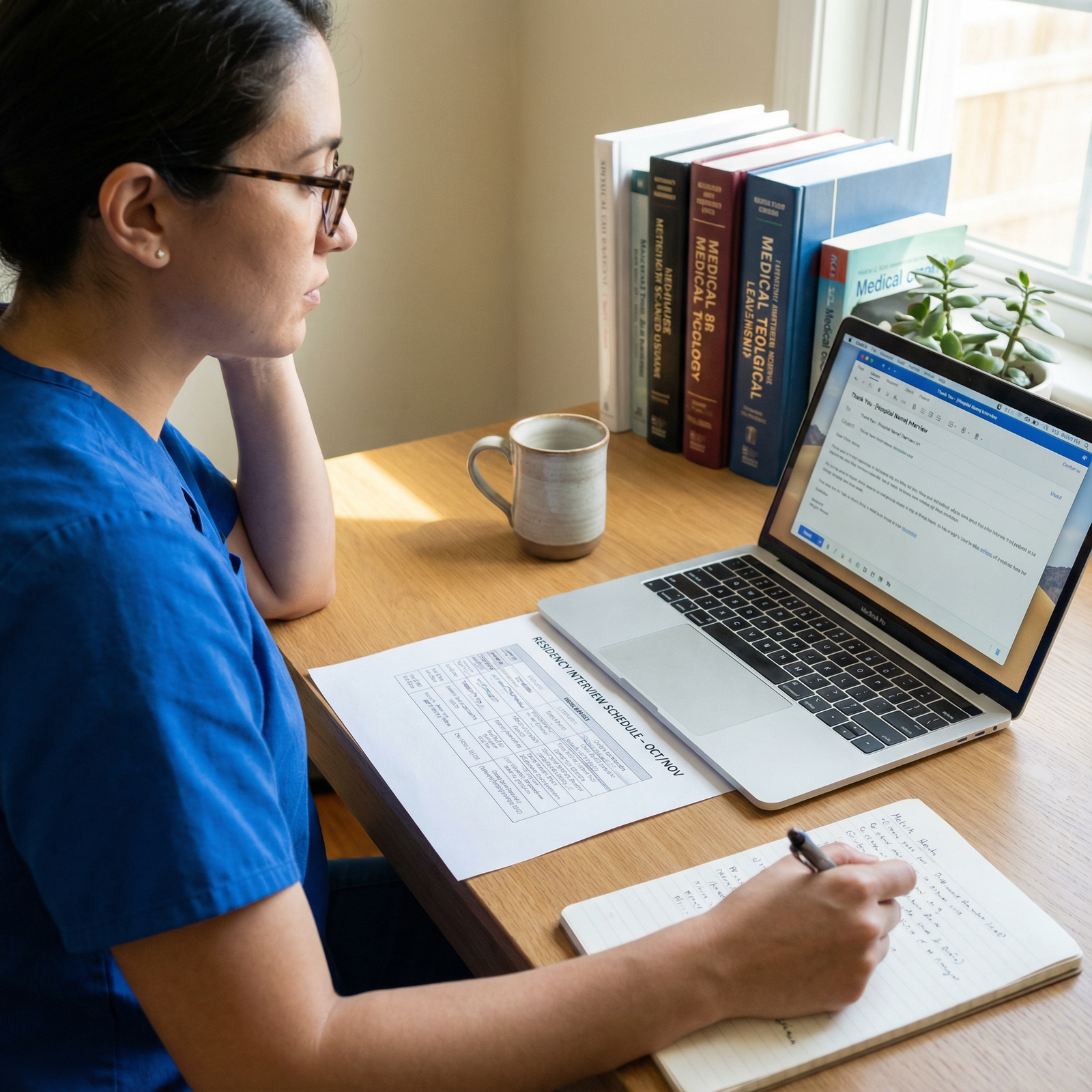

Step 1: Capture and clean up your research notes before you email

If you do not control your notes, you will send vague, useless emails. The timing matters.

Right after the interview day (same evening if possible), you should have a structured way to capture research-related details from each program.

Use a quick template per program:

- Who: specific person, correct spelling, title

- What: project(s) you discussed

- Hook: anything that linked you to them

- Future: anything they mentioned about next steps, timelines, or needs

Example note set right after interview:

- Who: “Dr. Anita Patel – Associate Program Director, runs sepsis outcomes lab”

- What: R01 on early biomarkers for sepsis; multi-center trial; focus on EHR data extraction + prospective validation

- Hook: I talked about my QI poster on sepsis bundle compliance + my experience cleaning EHR data in Epic for a retrospective CHF readmission project

- Future: She said, “We are always looking for residents who actually want to get into the data early on, even in intern year.”

That level of detail is what will let you write a sharp, specific follow-up. Not “Thanks again, I enjoyed hearing about research at your institution.”

You also want a basic system to organize this, especially if you are doing 12+ interviews.

| Column | Example Entry |

|---|---|

| Program | University Hospital Internal Medicine |

| Interview Date | 11/03/2025 |

| Faculty Name | Dr. Anita Patel |

| Role | Associate PD, Sepsis Outcomes Lab |

| Key Project Discussed | R01 on sepsis biomarkers |

| Your Overlap | EHR QI project on sepsis bundle compliance |

| Follow-Up Angle | Data interest, prospective trial involvement |

If you skipped this and your notes are a mess, fix that first before writing any follow-up. Otherwise, your email will sound generic because it will be generic.

Step 2: Understand what follow-up emails can and cannot do

Follow-up emails will not rescue a terrible interview. They also will not magically catapult you from the middle of a large rank list to #1.

But they can:

- Lock in name–face–topic association in the faculty’s mind

- Give them a concrete reason to say, “Yes, I remember this applicant” when ranking

- Signal seriousness about academic development, especially if you reference research clearly and concisely

- Create a small but real opening for you to reconnect later once you match (or in SOAP, if applicable)

Programs are flooded with bland emails. You stand out by being:

- Short

- Specific

- Accurate

- Respectful of their time

A good follow-up does not read like a cover letter. It reads like a professional, precise reminder that you are a resident they can work with.

Step 3: Structure of a research-focused follow-up email

Most applicants either write walls of text or three-line robotic notes. The sweet spot is about 150–200 words, with research woven in naturally.

Here is the basic structure:

- Subject line

- Polite opener / reminder of context

- One focused paragraph referencing research conversation

- Concise closing + signal of continued interest

- Signature with full name and ERAS AAMC ID (or equivalent)

3.1 Subject lines that actually help

Keep it simple and searchable:

- “Thank you – [Your Name], [Specialty] Interview [Date]”

- “Thank you – [Your Name], [Specialty] Applicant, Research Discussion”

- “Appreciation for Interview – [Your Name], [Specialty] [Season Year]”

You are not trying to be clever. You want them to find your email instantly if they search your name.

3.2 The opener: anchor who you are in 1–2 lines

Do not start with your life story.

Example:

“Dear Dr. Patel,

Thank you again for speaking with me during my interview day at University Hospital on November 3. I appreciated the chance to learn more about your work in sepsis outcomes and the residency’s overall research infrastructure.”

That is it. Who you are, where, when, what topic.

Step 4: How to reference the research conversation without overdoing it

This is the core. You are trying to hit a narrow target:

- 1–3 very specific details from your conversation

- 1–2 lines tying your background to their work

- Optional: 1 line expressing genuine enthusiasm for future involvement

You are not writing:

- A literature review

- A critique of their paper

- A list of 8 skills you bring to their lab

Keep it clean.

4.1 The “specific detail + bridge” formula

The easiest structure for the research paragraph is:

- Name the research area / project clearly

- Reference a specific element they told you about

- Bridge that to one relevant piece of your own experience

- End with a forward-looking, low-pressure sentence

Example 1 – Medicine research-heavy program:

“I especially enjoyed hearing about your R01-funded work on early sepsis biomarkers and your plans for the multi-center trial that will integrate EHR-derived risk scores into clinical workflows. Our conversation about the challenges of cleaning EHR data for outcomes research resonated with my experience leading a retrospective CHF readmission project, where I helped develop the extraction pipeline and basic analytic plan. The prospect of contributing to similar work as a resident, particularly early in training, is very exciting to me.”

Notice what this does:

- Names the grant level (R01) and topic – specific

- Mentions a concrete aspect (EHR-derived risk scores, multi-center trial) – shows you listened

- Connects to YOUR relevant work – not your entire CV

- Signals interest without begging for a job

Example 2 – More community program with growing research:

“Talking with you about the residency’s growing emphasis on QI and outcomes research, especially your project on reducing time to antibiotics in septic patients in the ED, was very motivating. My QI work on sepsis bundle compliance in our academic county hospital gave me first-hand experience with both the data challenges and the front-line workflow issues you described. I would be eager to build on that experience and help expand similar initiatives as a resident.”

Again: specific project, one connection, clear future orientation.

Step 5: Different scenarios and how to handle each

Not every research conversation is the same. Some of you talked granular methods; others just heard, “We’re trying to expand our research footprint.” Adjust accordingly.

5.1 Scenario A: You discussed a specific paper or project in detail

If you referenced a particular paper they wrote, or they walked you through an ongoing project:

Do this:

- Name the paper or project once

- Mention 1–2 detailed elements that stood out

- Connect one skill or experience of yours

Example:

“I appreciated our discussion of your recent JAMA paper on post-sepsis functional outcomes, especially the challenge of capturing long-term follow-up in a diverse patient population. Having worked on a registry-based study of post-ICU readmissions, I recognized many of the methodological trade-offs you described, and it reinforced my interest in outcomes research within critical illness.”

Do not do this:

- “I read five of your papers last night and found them all fascinating.” (Sounds like you are trying too hard.)

- “I think your choice of composite endpoint was suboptimal…” (You are not on their K-award review panel.)

If you truly have a substantial background in that exact area and you had a real back-and-forth during the interview, you can be a bit more technical but still humble.

5.2 Scenario B: You only had a brief, surface-level research mention

Maybe it was a busy day and the only research talk was, “We support scholarly projects in PGY-2 and PGY-3.” You can still use that.

Example:

“Although our time was brief, I was glad to hear about the department’s support for resident projects in hospital medicine and transitions of care. My prior work on discharge planning and 30-day readmission risk tools has been one of the most meaningful parts of my training so far, and the prospect of pursuing similar work with structured mentorship during residency is very appealing.”

You did not invent details they never said. You just anchored to the general structure and inserted your real interest and experience.

5.3 Scenario C: You had a strong, multi-topic academic conversation

If you really clicked with someone and covered multiple topics, resist the urge to recap everything. Choose one main thread.

Bad approach:

“I enjoyed talking with you about sepsis outcomes, resident QI curricula, the fellowship match, and program leadership philosophy…”

Better approach:

“I came away from our conversation about balancing resident autonomy with support, especially in the context of designing QI projects that are feasible in a busy inpatient service, feeling that your program aligns very closely with how I hope to grow. The way you described residents leading sepsis and heart failure QI initiatives, with structured mentorship and protected time, matched exactly what I am seeking in a training environment.”

One thread. One theme. That is what sticks.

Step 6: How much detail is too much detail?

Here is the part applicants get wrong. They think more scientific words = more impressive. Faculty think more scientific words = more skimmable fluff, 90% of the time.

As a rule:

- 1–2 technical phrases are fine if you truly understand them

- Anything that starts to feel like a methods section goes in the trash

- Focus more on your role and insight, not on the lab vocabulary

Let me show you the difference.

Overkill:

“I was particularly interested in your use of machine learning–based random forest models integrating time-series EHR variables and multi-omic plasma biomarkers to derive your sepsis risk stratification algorithm. In my prior work, I utilized LASSO regression and gradient boosting techniques…”

Faculty reaction: This feels like you are reciting buzzwords, or writing for a grant, not an email.

Better:

“I was especially interested in how your team is integrating EHR-based risk scores with plasma biomarkers to refine early sepsis detection. In my prior work on predictive models for readmission risk, I saw first-hand how crucial careful variable selection and clinical input are, beyond whatever the algorithm suggests. That combination of rigorous methods and bedside relevance is the type of work I hope to pursue in residency.”

You are still specific. But readable. You sound like someone who could collaborate on a project, not someone playing ‘impress the PI’ bingo.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Gratitude/Professionalism | 25 |

| Specific Research Reference | 35 |

| Your Relevant Experience | 25 |

| Future Interest/Signal | 15 |

Step 7: Referencing interest in future collaboration without being pushy

This is the part people are anxious about: “Can I say I want to work with them?” Yes. But you phrase it like a resident, not like a cold-email grad student begging for a position.

You are not asking for:

- A pre-match offer

- A guaranteed spot in their lab

- A summer fellowship

You are signaling that, if you match, you would welcome the chance to work with them.

Good lines:

- “If I have the opportunity to train at [Program], I would very much look forward to getting involved in this work.”

- “I would be excited to continue developing these skills under your mentorship as a resident.”

- “This conversation reinforced that [Program] is exactly the type of environment where I hope to grow as a clinician and researcher.”

Notice the conditional language. “If I have the opportunity…” You are not implying any inside track. Just interest.

Avoid:

- “I hope we can start working together soon on this project.”

- “Please let me know what I can start doing now to contribute to your trial.” (Before you match? No.)

- “I plan to rank your program #1 and would love for you to consider me strongly.” (This runs straight into match communication gray zones or violations depending on context.)

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Post-Interview Notes |

| Step 2 | Identify Research Details |

| Step 3 | Choose 1-2 Key Points |

| Step 4 | Draft Email Structure |

| Step 5 | Write Specific Research Paragraph |

| Step 6 | Check Tone and Length |

| Step 7 | Send within 48-72 Hours |

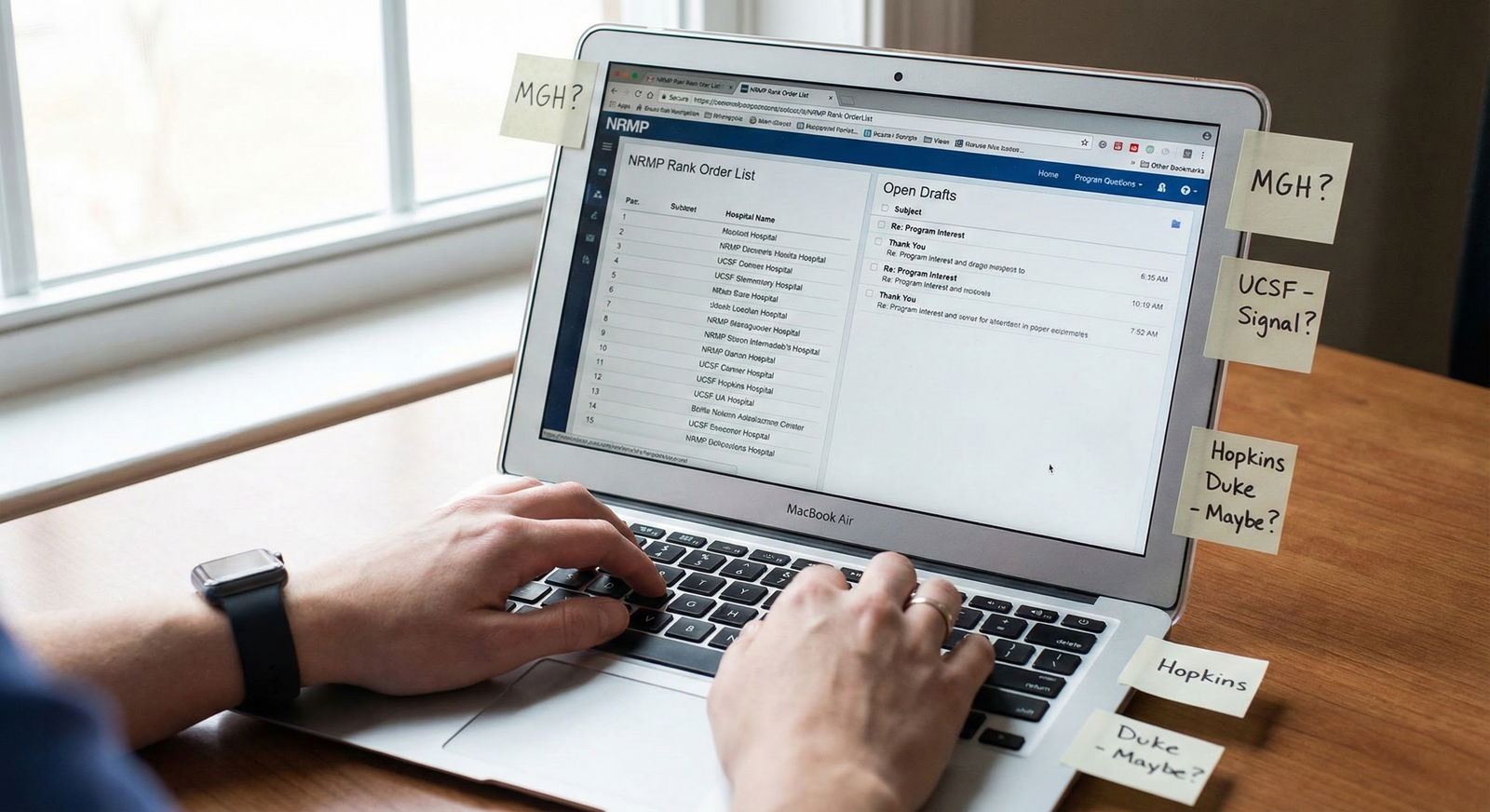

Step 8: Timeline and frequency – when and how often to reference research

You get two main windows to reference research:

- Initial post-interview thank-you (within 48–72 hours)

- Later update / interest email (if appropriate and truly necessary)

8.1 Initial thank-you: always

If research came up meaningfully in the interview, it belongs in the initial thank-you. This is your primary shot.

Timing: 24–72 hours. Not 3 weeks later.

Length: 150–200 words.

8.2 Later update: only when you have something real

If you publish a paper, present a major poster, or receive an award directly related to what you discussed, you can send a brief update.

Example:

Subject: “Update – [Your Name], [Specialty] Applicant (Research Presentation)”

Body:

“Dear Dr. Patel,

I hope you are well. I wanted to briefly share an update since my interview at University Hospital in November. The sepsis bundle QI project we discussed was accepted for an oral presentation at the upcoming Society of Hospital Medicine meeting. Preparing this has further solidified my interest in outcomes research and QI in sepsis care, which is one reason your program remains a top choice for my residency training.

Thank you again for your time and for the insightful conversation during interview season.

Best regards,

[Name], AAMC ID XXXX”

Two rules:

- Only send if the update is meaningful and clearly linked to what you discussed.

- Do not send multiple “just checking in” or “you’re my #1” emails.

One update per program, if justified, is enough. Many of you will not need it. A clean, strong initial follow-up is usually sufficient.

Step 9: Common mistakes in referencing research – and how to fix them

I have read hundreds of these emails. The same errors show up repeatedly.

Mistake 1: Vague “research is important to me” statements

Example: “Research is very important to me and I look forward to being involved in projects during residency.”

This says nothing. Every single applicant claims this.

Fix:

Anchor to one type of work and one prior example.

“I have found outcomes research in high-risk inpatients, especially sepsis and heart failure, to be particularly meaningful. Working on a QI project to improve timely antibiotics reinforced how much I enjoy projects that directly connect data with bedside care.”

Mistake 2: Over-selling minimal experience

Do not call your poster at a small regional conference “extensive research experience” if that is all you have.

Do this instead:

“Although my formal research experience is limited to a QI poster and small retrospective project, those experiences have made me eager to develop stronger methodological skills in residency, particularly in outcomes and implementation work.”

Honesty + forward orientation is more convincing than puffery.

Mistake 3: Misremembering or misrepresenting their work

This is fatal. If their work is on ARDS outcomes and you call it COPD, they will remember you – for the wrong reason.

If you are not 100% sure, keep the wording general but still anchored.

Instead of:

“…your R01 on COVID-19 ARDS…” (when actually it is on general ARDS outcomes)

Use:

“…your outcomes research in critically ill patients, including ventilated ICU populations…”

Safe, still correct, still specific enough.

Mistake 4: Turning the email into your research autobiography

Remember: they have your ERAS application. If your email spends four paragraphs listing every project you have done, you look insecure.

Your email is not your CV. It is a short professional reminder plus one well-chosen research connection.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Too Vague | 80 |

| Too Long | 65 |

| Over-technical | 40 |

| Inaccurate Details | 25 |

| Overly Self-Promotional | 55 |

Step 10: Sample polished emails (use as patterns, not scripts)

Let me give you two complete examples so you can see how this flows start to finish.

Example 1: Academic IM program, strong research focus

Subject: Thank you – Alex Chen, Internal Medicine Interview 11/3

“Dear Dr. Patel,

Thank you again for speaking with me during my interview day at University Hospital on November 3. I appreciated the opportunity to learn more about the residency and your work in sepsis outcomes.

I especially enjoyed hearing about your R01-funded project on early sepsis biomarkers and the upcoming multi-center trial integrating EHR-based risk scores into clinical workflows. Our conversation about the challenges of cleaning and validating EHR data for outcomes research resonated with my experience leading a retrospective CHF readmission project, where I helped develop the extraction process and basic analysis plan in collaboration with our biostatistics team. The chance to contribute to similar work as a resident, while building stronger methodological skills, is exactly what I am looking for in a training program.

Thank you again for your time and for sharing your perspective on resident development in research.

Best regards,

Alex Chen

Fourth-Year Medical Student, State University

AAMC ID: 12345678”

Note:

- 3 short paragraphs

- Clear research anchor

- One relevant past project

- Subtle but clear signal of interest

Example 2: Mid-size community program with focused QI efforts

Subject: Thank you – Maya Lopez, Family Medicine Applicant

“Dear Dr. Nguyen,

Thank you for the chance to speak with you during my interview at Riverside Family Medicine last week. I appreciated learning more about how the program supports resident-led projects in QI and population health.

Our discussion of your work on improving diabetes management through panel-based outreach and resident-run group visits was particularly memorable. My own QI project focused on increasing completion of retinal exams in a safety-net clinic, and I recognized many of the workflow and access issues you described. The way your residents are able to design and implement similar initiatives, with mentorship and protected time, is very appealing to me. If I have the opportunity to train at Riverside, I would look forward to contributing to these efforts.

Thank you again for your time and for an insightful conversation about resident education and community-focused research.

Sincerely,

Maya Lopez

Fourth-Year Medical Student, City Medical College

AAMC ID: 98765432”

Again, it is not complicated. Just specific, honest, and readable.

Step 11: Final checks before you hit send

Run through a rapid-fire checklist:

- Is the email under ~225 words?

- Does it name one clear research area or project, using correct terminology?

- Does it reference one relevant piece of your background, not your entire CV?

- Does it avoid match-violation language (“ranked #1”, “promise”, etc.)?

- Is the tone professional, direct, and not apologetic or overly effusive?

- Did you spell their name and program correctly?

If the answer is yes across the board, send it. Then stop obsessively re-writing it in your head. Move on to the next program while this one quietly works in your favor.

Key takeaways

- The only follow-up emails that matter are short, specific, and anchored in one clear research connection from your interview.

- Your job is not to impress with jargon, but to show you listened, you understood the work, and you can realistically see yourself contributing if you match there.

- A well-crafted research-focused follow-up will not singlehandedly secure your spot, but it will make you the kind of applicant faculty actually remember when they sit down with the rank list.