You are in your hospital office at 7:30 pm, finishing the last note of the day while an empty salad container sits next to the keyboard. Your RVUs look fine. Your chair says you are “valued.” Your paycheck disagrees.

Meanwhile, you just found out a same-specialty colleague in town, in private practice, makes 1.8–2.5x your salary and works roughly the same clinical hours. You are starting to ask the dangerous question:

Why am I still in academics?

This is the inflection point. You want higher income. You do not want to blow up your career, risk your license, or land in some predatory arrangement that burns you out faster than academics did.

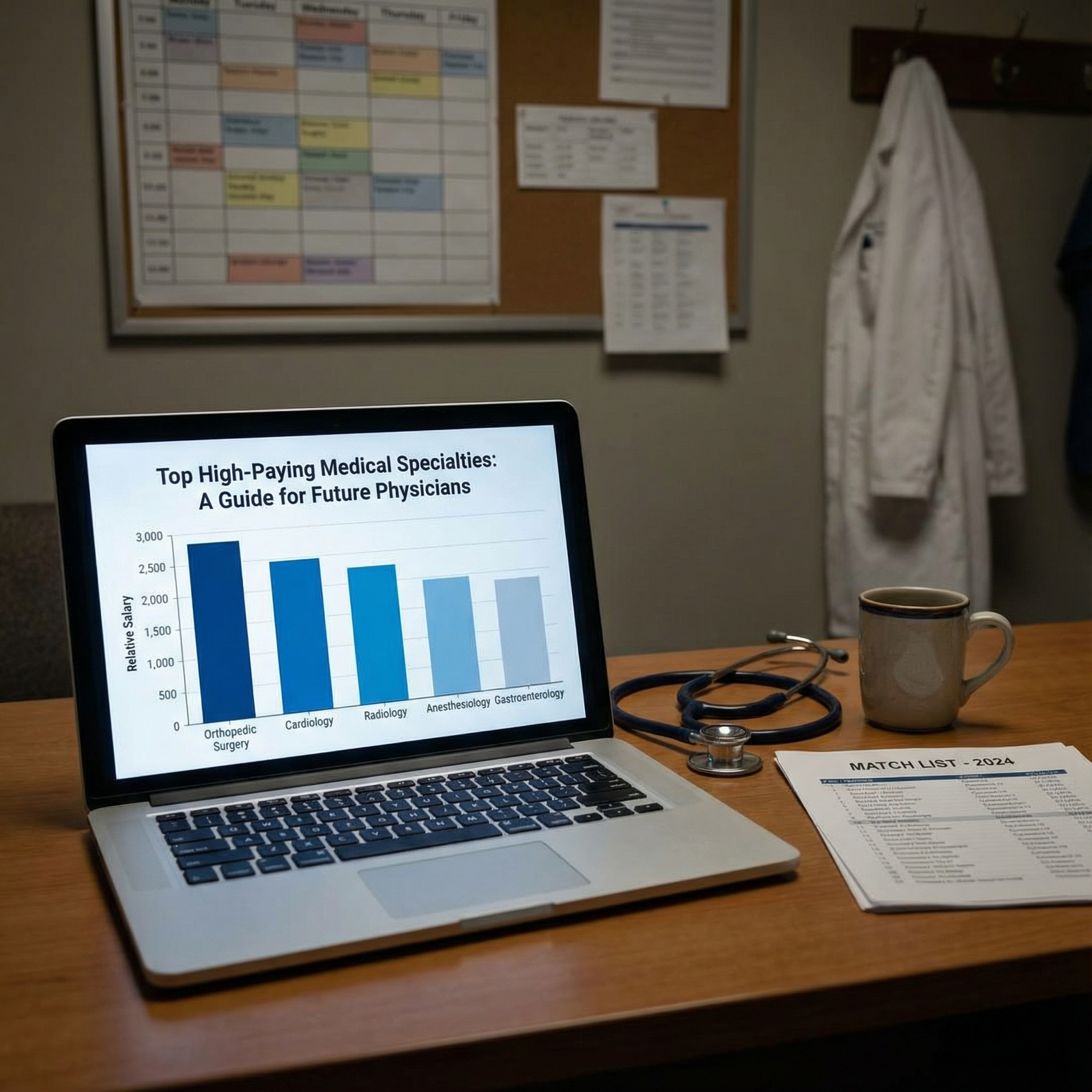

Let me walk you through how to move from academic medicine to private practice deliberately—especially in the higher-paid specialties (ortho, neurosurgery, cardiology, GI, derm, anesthesia, radiology, etc.)—without stepping on landmines.

1. Know Your Starting Point: Academic vs Private Practice Reality

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Orthopedics | 2.2 |

| Cardiology | 1.8 |

| GI | 2 |

| Radiology | 1.6 |

| Anesthesia | 1.7 |

| Derm | 2 |

Those bars are not fantasy. In the highest paid specialties, I routinely see:

- Attending in academics:

- Ortho trauma: $450–650k

- Interventional cardiology: $500–750k

- GI with ERCP: $450–700k

- Same specialty in private practice:

- Ortho: $900k–$1.5M+ (with partnership)

- Interventional cards: $900k–$1.3M+

- GI: $900k–$1.2M+

Not always. Not everywhere. But often enough that pretending it is rare is just denial.

The trade: Money vs stability (and myth)

The usual academic sales pitch:

- “Job security”

- “Protected time”

- “Prestige”

- “Mission-driven environment”

What you actually get, in many places:

- Annual “budget shortfall” drama

- “Protected time” steadily eroding

- Committees, politics, 3 different EMR logins

- Grants harder to get, harder to keep

Private practice has its own risks:

- Income variability

- Overhead

- Business risk

- Need to think like an owner, not an employee

But in higher-paid specialties, the raw dollars are simply larger, and you have more room to build a safety margin if you are systematic.

Your goal: Increase income without increasing existential risk to your career, license, or sanity.

2. Do a Hard, Numbers-Only Self-Assessment

Before you polish your CV or whisper to a recruiter, answer three financial questions. On paper. No hand-waving.

Step 1: Calculate your real current compensation

Include:

- Base salary

- Productivity bonus (average of last 2–3 years)

- Stipends (call pay, medical directorship, admin roles)

- Retirement contributions (employer match, 401a, 403b)

- Health insurance and other benefits (estimate a dollar figure)

Make it a single number: Total annual comp = $X

Then calculate: $/clinical day and $/RVU if you can.

| Item | Academic Current | Private Practice Target |

|---|---|---|

| Total Annual Comp | $450k | $900k |

| Work RVUs | 7,000 | 9,000 |

| Comp per RVU | $64 | $100 |

| Call Stipend | Included | Separate +$80k |

| Retirement Contribution | 5% | 15% |

You cannot fix what you have not quantified.

Step 2: Define your “walk-away” and “worth-the-risk” numbers

Two concrete thresholds:

Walk-away number

The minimum guaranteed comp you would accept to leave academics, given the loss of tenure, title, etc.

Example:- Current comp: $450k

- Walk-away: $650k with a 2-year guarantee, reasonable call, and no insane non-compete.

Worth-the-risk number

The number that makes the transition risk clearly rational.

Example:- Worth-the-risk: $900k+ realistic earnings within 3 years, with partnership track defined.

Write them down. These are your filters.

Step 3: Audit your risk profile

Be blunt:

- How much do you have in:

- Cash / liquid savings

- Retirement accounts

- Debt (student loans, mortgage, lifestyle bloat)

- How many dependents, and how fragile is your current setup?

If you are 2–3 months from being cash-broke, you do not want a high-variability, eat-what-you-kill model out the gate. You want:

- 1–2 year income guarantee

- Strong call pay

- Clear partnership path

We will structure this properly in a minute.

3. Pick the Right Private Practice Model (Not All Are Equal)

This is where people screw up. They chase the biggest headline number and ignore the structure.

The four common models

Hospital-employed “private practice lite”

- You are still an employee, but in a more productivity-driven environment, often with better comp than academics.

- Pros: More stable, benefits handled, less business complexity.

- Cons: Still bureaucracy, RVU grind, admin control.

Large single-specialty or multi-specialty group

- Equity/partnership usually available.

- Formalized call pools, ancillaries, real negotiating leverage with payers and hospitals.

- Pros: Scale, infrastructure, exit value when you retire.

- Cons: Politics, buy-in costs, sometimes opaque formulas.

Small group practice (3–10 physicians)

- “Classic” private practice.

- Pros: Autonomy, flexibility, direct impact on income.

- Cons: Business risk, more reliance on a small number of partners, succession issues.

Solo or micro-practice

- Highest autonomy, potentially very high earnings in derm, pain, some procedural fields.

- But this is not usually the first jump from academics unless you have serious risk tolerance and business skill.

For highest paid procedural specialties, the sweet spot for most academic refugees is:

- Large single-specialty or robust multi-specialty group

OR - Hospital-employed but with clear RVU bonus, call pay, and side ancillaries (e.g., imaging center, ASC share possible downstream).

4. Build a Safe Transition Timeline

Do not wake up, get mad after one bad faculty meeting, and start emailing recruiters from your work email.

You want a 6–18 month runway, depending on complexity.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Months 0-3 - Financial audit and goals | 0 |

| Months 0-3 - Quiet market research | 0 |

| Months 3-6 - Talk to recruiters and peers | 1 |

| Months 3-6 - Site visits and interviews | 2 |

| Months 6-9 - Compare offers, negotiate terms | 3 |

| Months 6-9 - Legal review of contracts | 3 |

| Months 9-12 - Finalize exit timing | 4 |

| Months 9-12 - Credentialing and licensing | 4 |

| Months 12-18 - Notice to institution | 5 |

| Months 12-18 - Transition to new practice | 6 |

Phase 1 (Months 0–3): Quiet prep and intel

Financial and career audit (we already walked through this).

Market scan:

- Talk off-the-record to:

- Former co-residents who left for private practice

- Industry reps (device, pharma) – they know which groups are thriving

- Subspecialty society colleagues

- Ask very specific questions:

- “What is the realistic year 1, 3, 5 comp?”

- “What is partnership buy-in and what does it actually buy?”

- “Any red flags on leadership or billing practices?”

- Talk off-the-record to:

Update your CV, quietly

No mass emails. No public “I’m looking” posts yet.

Phase 2 (Months 3–6): Serious exploration

Start taking recruiter calls, but filter them ruthlessly:

- Ask for:

- Sample contract (redacted is fine)

- Comp structure one-pager

- Call schedule and call pay

- Non-compete radius and duration

- If they cannot provide those up front, they are wasting your time.

At the same time, schedule shadow days or site visits with 2–4 high-potential groups. Watch the vibe:

- Are partners burned out or energized?

- What do mid-levels say about the place when partners are not in the room?

- How are staff treated—especially nurses and techs?

Phase 3 (Months 6–9): Offers and contract reality

By this point you should have:

- 2–3 serious options

- Rough term sheets or full contracts

Now you need structure, not vibes.

5. Structure Your First Private Practice Deal for Safety

This is where the “increase your income safely” part is won or lost.

Non-negotiable: Outsourced contract review

Pay for a healthcare attorney who does physician contracts all day, not your cousin who does real estate closings.

You need explicit attention to:

- Non-compete terms

- Termination clauses

- Productivity formulas

- Partnership terms

- Ownership of charts, ancillaries, intellectual property

7 contract terms you must understand cold

Base salary and guarantee period

- For high-paid specialties, a 1–3 year guarantee is common.

- You want the guarantee to:

- Cover your “walk-away” number.

- Not be so high that RVU or production targets become physically impossible.

Production formula

Some version of:- wRVU-based: $X per wRVU after base threshold

- Collection-based: You keep Y% of your collections after overhead

- Hybrid: Base + bonus for hitting certain gross or net numbers

You need to model 3 cases:

- Conservative: 75% of expected volume

- Expected: Baseline volume they are promising

- Aggressive: 125–150% volume (to see upside)

Call requirements and call pay

For high-income specialties, call is where people get squeezed.

Clarify:

- Frequency: “Every 4th night” is not the same as “Home call with real backup”

- Mandated additional shifts

- Pay for extra call beyond baseline

-

This is the clause that can ruin your life if you ignore it.

You want:

- Shorter duration: 6–12 months, 18 months max

- Smaller radius: Often 5–15 miles; 50 miles in a major metro is absurd

- Narrow scope: Restricted to your exact specialty, not “any medical practice”

-

In surgical and procedural specialties, partnership is where the real money sits—facility fees, ancillaries, imaging, ASC ownership.

You must know:

- Exact timeline (2 years? 3 years?)

- Criteria (purely time-based, or performance + votes?)

- Buy-in amount (cash, financing, sweat equity)

- What you actually own: AR, equipment, building, ASC shares, imaging, etc.

Termination terms

- Without cause: How much notice? 60–180 days is typical.

- For cause: Define it tightly; avoid vague “professional conduct not aligned with practice values” language.

-

- Claims-made policies require tail coverage when you leave.

- Who pays for tail? This is not trivial; for high-risk procedural specialties, tail can be six figures.

6. Risk Controls: How Not to Blow Up Your Career

Here is where people get hurt:

- They leave academics, join a sketchy group, discover coding or billing is… “creative.”

- Or they sign a monster non-compete and then realize the group is toxic.

- Or they get pushed to clinically unsafe volumes.

You manage these risks deliberately.

Clinical and compliance safety checks

Before you sign:

- Ask bluntly about:

- Use of APPs (scope, supervision)

- Coding practices (upcoding culture is a huge red flag)

- Average daily/OR volume expectations

- Ask to see:

- Sample clinic schedules

- Typical OR block utilization

- Any recent audits or compliance issues (Medicare, commercial payer disputes)

Financial safety: Build a multi-layered buffer

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Emergency Fund | 40 |

| Transition Costs | 25 |

| Malpractice/Tail Contingency | 20 |

| Lifestyle Cushion | 15 |

For a major transition like this, especially into higher-volatility income, I want physicians to have:

- 6–12 months of core living expenses in cash equivalents.

- A separate transition fund for:

- Moving costs

- Temporary housing (if needed)

- Gaps in pay during credentialing

- A contingency line for unexpected:

- Tail coverage

- Early partnership buy-in opportunity

- Business expenses if they are partially responsible

7. Specialty-Specific Realities (Highest Paid Fields)

Let me be more concrete for a few of the big-earning specialties.

| Specialty | Academic Typical | Private Practice Goal | Key Private Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthopedic Surgery | $450–700k | $900k–$1.5M+ | High call, overhead |

| Interventional Cards | $500–800k | $900k–$1.3M+ | Call, hospital politics |

| Gastroenterology | $450–700k | $900k–$1.2M+ | Endoscopy access |

| Radiology | $400–650k | $700k–$1.1M+ | Telerad competition |

| Anesthesiology | $350–600k | $600k–$1.0M+ | Staffing, payer mix |

| Dermatology | $350–500k | $700k–$1.2M+ | Cosmetic vs medical mix |

Orthopedics

Key points:

- ASC ownership is often the biggest wealth lever.

- You need to know:

- Who owns the ASC(s)?

- Are you eligible for shares?

- How are block times allocated between partners and new docs?

Safety tactic:

- Avoid joining as pure “worker bee” with zero path to equity unless you are using it as a stepping stone with eyes fully open.

Interventional cardiology

Risk centers:

- Call and night work expectations.

- Pressure to take every case, all hours, with minimal backup.

Safety tactic:

- Nail down call frequency and backup coverage in writing.

- Ask about recent staffing changes; unstable groups often burn through new hires.

Gastroenterology

Levers:

- Endoscopy center ownership.

- High procedure volume vs clinic grind.

Safety tactic:

- Clarify how scopes are allocated and who controls the endoscopy schedule.

- Get real historical volume numbers, not “We’re very busy.”

Radiology

Issues:

- Teleradiology competition.

- Day vs night coverage.

- RVU or per-study comp formulas that can quietly erode.

Safety tactic:

- Understand exactly how new imaging contracts are obtained and who negotiates them.

- Ask how they have handled declining reimbursements over the past 5 years.

Anesthesia

Issues:

- Dependence on hospital contracts that can be lost.

- CRNA/AA staffing and supervision dynamics.

Safety tactic:

- Ask explicitly about the term and security of existing hospital contracts.

- Clarify your role relative to mid-levels.

Dermatology

Upside:

- Blend of medical derm, procedural derm, and cosmetics.

- Ancillaries: products, cosmetic procedures, MOHS, pathology.

Safety tactic:

- If cosmetics are a big part of revenue, look closely at payor mix, cash vs insurance, and local market competition.

8. Execute the Exit Without Burning Bridges

You want two things:

- A strong relationship with your prior institution (for referrals, moonlighting, or even a potential academic return later).

- No legal or reputational mess.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Sign new contract |

| Step 2 | Plan exit timing |

| Step 3 | Review current contract |

| Step 4 | Give formal notice |

| Step 5 | Transition patients |

| Step 6 | Close out research and admin |

| Step 7 | Final day in academics |

| Step 8 | Start private practice |

Stepwise clean exit

Review your existing academic contract

- Notice period (60–180 days common).

- Any restrictive covenants (some academics have them).

- Obligations for grants, administrative roles, or leadership positions.

Time your notice correctly

- Ideally, you give notice once the new private practice contract is signed and credentialing is underway.

- Do not surprise them 2 weeks before new job; bad look, unnecessary enemies.

Control the narrative

Your script, more or less:“I have decided to pursue an opportunity in private practice that aligns better with my long-term goals and family needs. I am grateful for my time here and want to ensure a smooth transition for patients and the team.”

That is it. You do not owe anyone a speech on RVUs or admin incompetence.

Finish well

- Close charts.

- Hand off complex patients.

- Wrap research or transfer it cleanly if possible.

- Do not turn into a ghost for your last 90 days.

9. First 12–24 Months in Private Practice: How to Actually Capture the Upside

The move alone does not make you rich. Execution does.

Priorities in year 1

Volume and efficiency ramp-up

- Learn the systems: EMR, scheduling, billing.

- Optimize clinic templates: cluster procedures, minimize dead time.

- Get face time with referrers:

- Hospitalists

- PCPs

- ED docs

- Other specialists

Guardrails against unsafe patterns

- Say no to volume that clearly exceeds safe practice.

- Escalate systemic safety issues early (and document).

Track your numbers monthly

At minimum:

- wRVUs or collections

- Payer mix

- No-show/cancellation rates

- OR or procedure room utilization

This is a business now. You are not a cog in an academic machine. If your practice manager cannot or will not give you these numbers, that is a problem.

Years 2–3: Ownership and leverage

- Push for partnership if promised.

- Get your arms around:

- Practice P&L (you need to see it).

- Overhead breakdown.

- Ancillary revenue flows.

This is where your income in the highest paid specialties can truly separate from academic levels—safely—if the foundation is solid.

FAQ (Exactly 2 Questions)

1. Should I tell my academic leadership I am exploring private practice before I have an offer?

No. Keep exploration quiet until you have at least one serious offer and have reviewed your contract with an attorney. Premature disclosure just destabilizes your current job and can trigger subtle retaliation (committee assignments, schedule changes, etc.) without giving you any advantage. Your first “official” conversation should happen after you are confident a move is viable and roughly when you are ready to time your notice.

2. What if I move to private practice and hate it—can I go back to academics?

Yes, but you want to keep that path open deliberately. Leave on good terms, maintain contact with a few trusted academic colleagues, and keep some scholarly activity alive if possible (occasional talks, modest publication involvement). Just recognize that going back often means re-entering at lower pay with more clinical pressure than you had when you left. This is another reason to choose your first private practice carefully, with realistic expectations and legal protection, rather than “try it and see” with a poorly structured deal.

Key points:

- Do a hard, numbers-based assessment of your current academic comp and define clear walk-away and worth-the-risk targets.

- Choose the right private practice model and structure your contract—especially non-compete, partnership, call, and tail coverage—to protect your downside.

- Execute a disciplined transition and treat the first 1–3 years in private practice like building a business, not just changing employers, to safely capture the higher-income upside.