It’s 9:45 p.m. You’re still scrubbed in, watching an attending vascular surgeon close a case that started at 3:10 p.m. This is the third add‑on of the day. OR turnover has been a mess, anesthesia’s short-staffed, and the surgeon just muttered under his breath, “I should have done derm,” while tying the last knot.

You laughed. He didn’t.

Let me tell you what actually happens when the “highest paid” attendings get 10–15 years out and look back at their specialty choice. I’ve heard these conversations at 1 a.m. in call rooms, on post‑call breakfasts, and at recruitment dinners after a couple glasses of wine. They’re not in the glossy salary surveys. They’re in the “If I could do it over again…” confessions.

We’re going to talk about surgery, ortho, neurosurgery, IR, cardiology, GI, anesthesia, EM — the usual high‑pay suspects. And what those people really regret.

Not the Instagram version. The version they only tell each other.

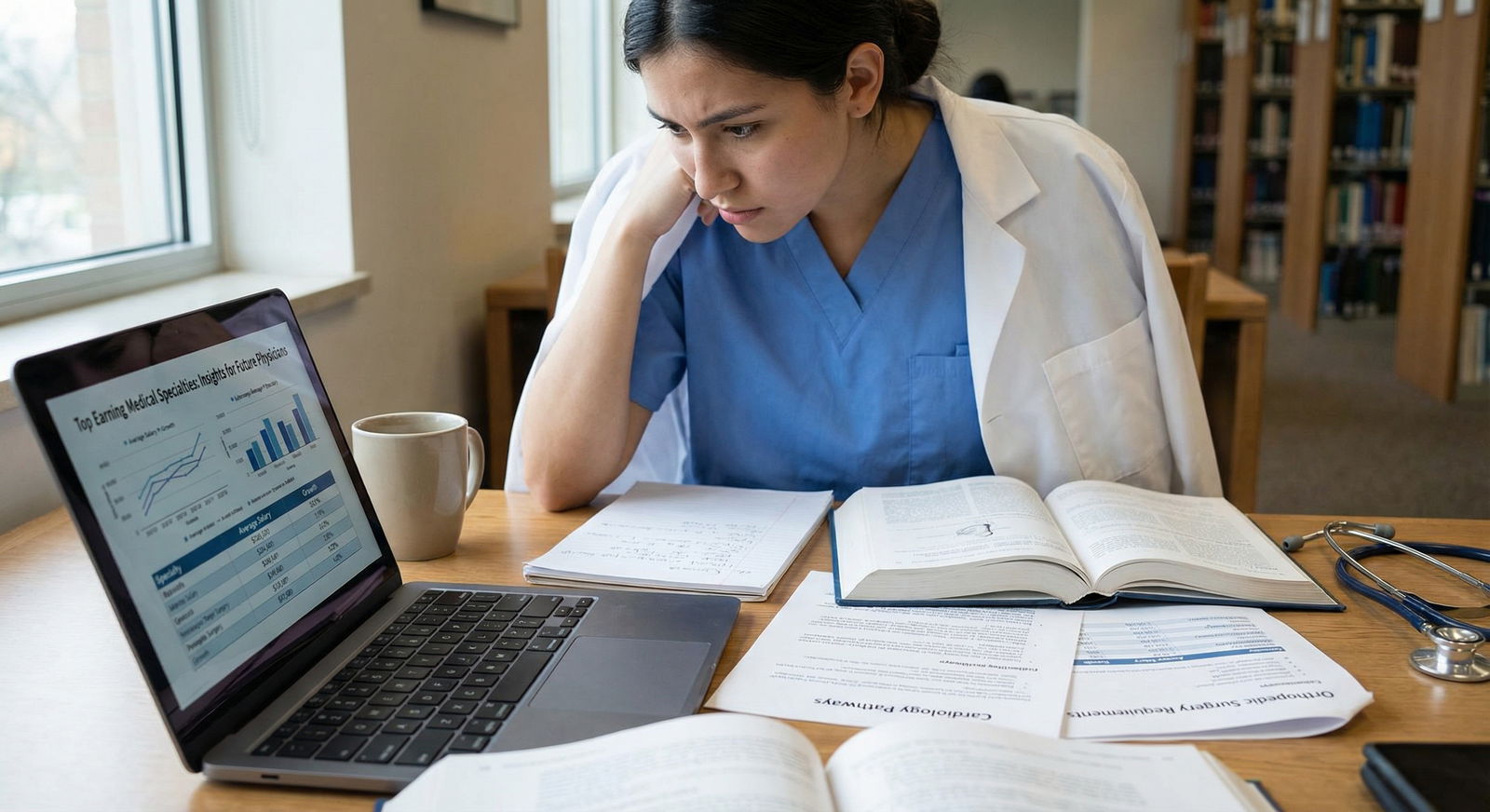

The Money vs. Life Tradeoff (that you misprice as a student)

The first big lie: everyone pretends they’ve been perfectly rational about “lifestyle vs. compensation.” They haven’t. Most of them priced their time wrong when they were 24.

You as a student look at the MGMA or Doximity numbers and see:

| Specialty | Approx Annual Compensation |

|---|---|

| Orthopedic Surgery | $650,000+ |

| Neurosurgery | $750,000+ |

| Interventional Cardiology | $700,000+ |

| Gastroenterology | $600,000+ |

| Dermatology | $500,000+ |

You think: “I’ll grind in residency, cash big checks later, then relax.” Attendings in high-paid fields made the same calculation. A lot of them regret it.

Not because the money isn’t real. It is. I’ve seen spine surgeons clear seven figures. Interventional cardiologists with ownership stakes in cath labs making numbers that would make tech bros blink.

They regret that they dramatically underestimated:

- How exhausted they’d feel at 40.

- How much call destroys the experience of being off.

- How golden handcuffs work when your burn rate creeps up with your income.

I remember an interventional cardiologist, mid‑40s, two kids, huge house, nice cars. We were eating bad pizza between STEMIs. He said, “I’d trade 300k a year to never be on call again. Easily.” And he meant it. The problem? His life was already built around the higher number.

So the core regret for many high‑earners isn’t “I hate medicine.” It’s: “I sold future me for a pay bump that doesn’t feel worth it anymore.”

That’s not lifestyle fluff. That’s the thing they only admit to peers.

Surgery, Ortho, Neurosurgery: The “I Didn’t Understand the Cost of Call” Regret

You know the stereotype: surgeons are tough, love the OR, love the grind. Some do. Those are the ones who age best in these fields.

The ones who don’t? They carry a specific regret: they never really understood what chronic, high‑intensity call does to a human being over 10–20 years.

Attendings will say things like:

- “If call ended at 40, I’d be fine. But it doesn’t.”

- “I can’t remember a week I slept through without looking at my phone.”

- “I missed more of my kids’ stuff than I thought I would. At the time, it all felt non-negotiable.”

Let’s break this down by type.

General surgery and subspecialties

The money jumps when you add complexity: hepatobiliary, colorectal, surgical oncology, vascular. The regret: your cases get longer, sicker, and more urgent. Emergencies find you.

Common quiet regrets I’ve heard:

- “I trained at a big academic center, assumed I’d always have residents. Now I’m in a community hospital doing 4 cases back-to-back with mediocre support.”

- “I didn’t realize how many nights I’d be the only surgeon comfortable with X, so everyone calls me.”

The part you don’t see as a student: the constant background anxiety. That ping at 10:45 p.m.: “We have a perf.” You can’t really have a glass of wine with dinner most nights. You’re always in a maybe‑working state.

Orthopedic surgery

Ortho is famous for “work hard, play hard, get paid.” A lot of that is accurate. But talk to older orthopods and you’ll hear regrets around:

- Physical wear and tear. Backs destroyed from leaning over tables, shoulders wrecked from power tools, hands arthritic. I know an ortho who had to cut his caseload in half by 52 because his own spine couldn’t handle it.

- RVU treadmill. “I thought partnership meant freedom. It meant a higher bar. I’m hustling harder at 45 than I did at 35 because now I carry the overhead.”

And the competitive, volume‑driven culture? Fun in your 30s, less cute in your 50s when younger guys are outproducing you and admin watches your numbers.

Neurosurgery

Neurosurgeons will rarely admit regret publicly. Too much ego invested. In call rooms and conferences, though, you’ll hear:

- “I should have done IR.”

- “If you don’t eat this job, it eats you.”

Their core regret isn’t usually the field itself. It’s the total colonization of their lives. They can’t do “half‑neurosurgery.” You’re signing up for 7-year residency plus a career where a single phone call can turn your night into an 8‑hour case on a ruptured aneurysm.

I’ve heard exactly this line from a mid‑career neurosurgeon: “We sell residencies as a finite period of torture. That’s a lie. The responsibility and the 3 a.m. catastrophes increase as an attending.”

Cardiology & GI: The “Procedures Pay, but the Grind is Endless” Regret

Interventional cardiology and GI probably give the highest income‑to‑training length ratio outside neurosurgery. Cath lab, scopes, high volume, high RVUs.

And the same attendings will look right at students during fellowship interviews and say, “This is the best job in the world.” Some mean it. Some are also locked into a business model they privately resent.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Interventional Cards | 7 |

| GI | 5 |

| Ortho | 4 |

| Neurosurg | 7 |

(Values = average call nights per month; real numbers vary, but that’s the ballpark in many groups.)

Interventional cardiology

What they regret:

- Being chained to the STEMI pager. I’ve seen guys sitting at their kid’s recital on the aisle seat, bag ready, always half‑distracted.

- Underestimating non-procedural crap. Prior auths, clinic (“just” 20 patients), hospital politics over cath lab time.

- Choosing prestige over fit. “I picked the biggest group with the fanciest toys. I should have picked the one with a sane call schedule.”

One cardiologist told me bluntly: “I thought being the STEMI cowboy would feel heroic at 45. It just feels like getting older, faster.”

Gastroenterology

GI regrets are different. Less about acute crisis, more about the monotony and production pressure.

Common themes:

- “I underestimated how soul-numbing 10–15 routine colonoscopies a day can be.”

- “I basically run a factory now. Scope, dictation, scope, dictation.”

- “We built our incomes on volume. Then everyone started fighting over the same pie.”

A lot of GI folks carve out niches (IBD, motility, hepatology) just to feel like they’re doing more than surveillance forever. The ones who don’t? They often quietly talk about derm or radiology with a hint of envy: “Still paid, way less throughput stress.”

Anesthesia & EM: The “I Picked for Lifestyle… Then the System Changed” Regret

Now we get into a different category of regret. These are the specialties a lot of people chose for lifestyle and flexibility, and then watched the ground move under them.

Anesthesiology

A generation ago, anesthesia was considered a sweet spot: good pay, predictable work, some flexibility, low clinic baggage. Then:

- Corporate groups consolidated.

- CRNA scope expanded.

- Contracts flipped every few years.

I’ve heard older anesthesiologists say, “If I were a med student now, I’d think twice. The leverage is shifting.”

Their regrets:

- Underestimating commoditization. “I didn’t think I’d be bidding for my own job against CRNA-heavy models by my 50s.”

- No ownership. Many never built equity in anything, just high W‑2 incomes that can evaporate with a hospital’s RFP decision.

- The invisibility. Some get tired of being the “gas guy/gal” — patients forget they existed five minutes after discharge.

The day you watch a long‑time private group lose its contract to a national company and see 20+ attendings facing either relocation or worse terms, you understand this regret viscerally.

Emergency medicine

EM is going through its own reckoning, and attending regrets are getting louder.

The classic EM pitch: good money, flexible scheduling, no pager, shift work. The reality many mid‑career EM docs now face:

- Oversupply from new residencies.

- Corporate staffing and aggressive metrics.

- Escalating violence and burnout in overcrowded EDs.

I know attendings who say openly: “If I were an M3 now, I would not choose EM.” That’s not rare talk anymore.

Their regrets center on:

- Underestimating night shift aging. Rotating nights into your 40s and 50s is brutal. Your body stops bouncing back. I’ve seen EM docs trying to shift into admin or urgent care just to escape nights.

- Believing the ‘flexibility’ myth. Yes, you can trade shifts. But you’re still on a hamster wheel of nights, weekends, holidays. You just slide the misery around.

- Job security illusions. Many assumed “EDs always need docs.” Then groups lost hospital contracts overnight and dozens of EM physicians were scrambling.

They make solid money, yes. But a lot of them regret anchoring their career to a specialty whose working conditions deteriorated faster than they expected.

Radiology & IR: The “Invisible and Irreplaceable at the Same Time” Regret

Radiology straddles a weird line: high pay, intellectually interesting, better hours in many settings. Sounds great. The regrets are more subtle — they tend to surface 10–15 years in.

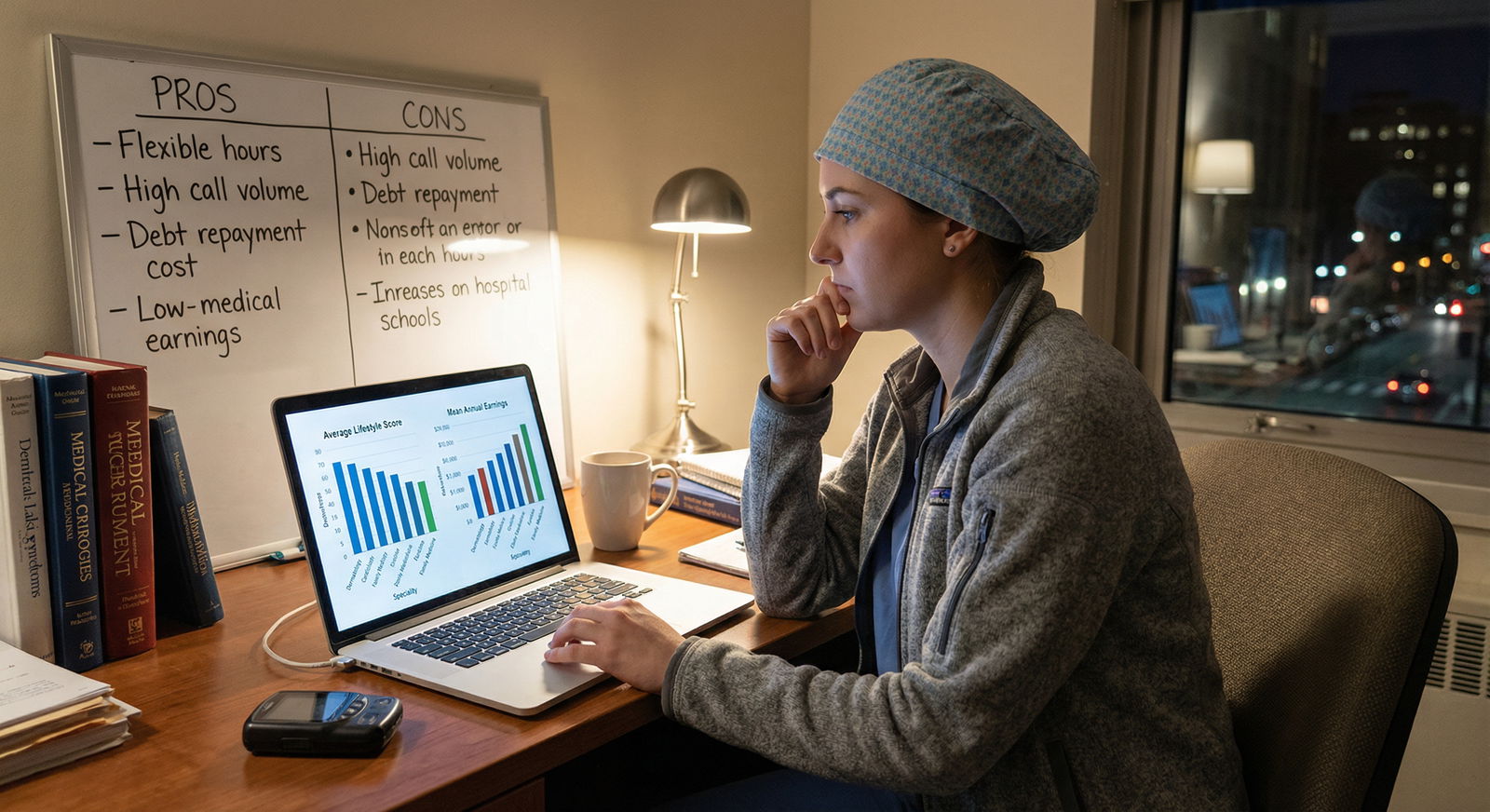

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Ortho | 4,9 |

| Neurosurg | 3,9 |

| IR | 5,8 |

| Cards | 5,8 |

| GI | 6,8 |

| Anesthesia | 7,7 |

| EM | 6,7 |

| Rads | 8,7 |

| Derm | 9,7 |

(x-axis = lifestyle 1–10, y-axis = pay 1–10, as rated informally by attendings; higher is better.)

Diagnostic radiology

Rads regrets:

- Isolation. “I didn’t realize how much I’d miss patient interaction. I basically live in a dark room.”

- Being the bottleneck for everyone. Constant interruptions: “Can you look at this stat?” “I need a read right now.” It’s death by 1,000 “quick questions.”

- AI anxiety + telerad pressure. They won’t say AI will replace them outright, but I’ve heard: “The pressure to read more, faster, never goes away. We’re racing the RVUs and the algorithms.”

Many radiologists are financially comfortable but emotionally checked out. The regret isn’t usually “I chose wrong.” It’s “I optimized for the wrong part of myself. I thought I’d be happy being left alone with images. Turns out I actually like people.”

Interventional radiology

IR looks sexy as hell from the outside. Cool procedures, good money, growing field. The hidden regret: you inherit the worst of multiple worlds — procedure demands, call, and turf battles.

IR attendings will complain about:

- Being “the fix it at 2 a.m.” person for everyone else’s complications.

- Nonstop pressure to build a “service line”: PAD clinic, oncology procedures, venous interventions. It’s not just doing cool cases; it’s running a business.

- Constant boundary fights with vascular surgery, cardiology, even neurosurgery.

More than one IR has told trainees privately: “I love the procedures. I hate the politics and the expectation that I become a full‑time marketer for my own practice.”

The Personal Life Tax: Divorce, Kids, and the “I Wasn’t There” Regret

This is the part most attendings won’t spell out unless they really trust you: the family cost.

I’ve sat in lounges with spine surgeons on their second divorces, EM docs paying child support for kids states away, cardiologists trying to repair relationships with teenagers they barely saw for a decade.

The pattern is consistent across high‑pay specialties with heavy call or irregular hours. Regrets they’ll voice quietly:

- “I built my identity around being the indispensable doctor. That’s cute for 10 years. Then you notice your kids stopped asking if you could come.”

- “I assumed my partner would just ‘understand’ my schedule forever. That was naive and selfish.”

- “I thought making enough money would compensate for not being around. It doesn’t. Kids don’t care about your RVUs.”

Here’s the truth: the system will never tell you to go home. Your colleagues won’t protect your time. Administrators certainly won’t. If you choose a specialty where the hospital always “needs” you, you have to decide where the line is.

The attendings who regret their choice most are often the ones who never drew a line until it was too late.

The Identity Trap: When Leaving Isn’t Really an Option

Another quiet regret among high‑earners: they feel trapped. Not just financially, but psychologically.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Choose High Pay Specialty |

| Step 2 | Long Training and Subspecialty |

| Step 3 | High Income and Lifestyle Inflation |

| Step 4 | Burnout or Dissatisfaction |

| Step 5 | Consider Switching or Cutting Back |

| Step 6 | Negotiate or Change Practice |

| Step 7 | Stay Trapped and Resentful |

| Step 8 | Can Adjust? |

You spend 7–10 years training to be, say, a neurosurgeon or interventional cardiologist. Your entire sense of competence and status is tied to doing something that almost no one else can do. Then you burn out. Or get injured. Or just stop wanting to live on a STEMI or aneurysm pager.

On paper, you could pivot: consult, admin, move into a lower intensity role. In reality, a lot of them can’t stomach the loss of identity.

I’ve heard variations of:

- “What else am I qualified to do that doesn’t feel like a demotion?”

- “I can’t go from this salary to half and feel okay about it, even if logically it’s fine.”

- “If I’m not Dr. X, the go‑to for Y, who am I?”

So they stay. They keep taking calls they hate, doing cases they no longer find meaningful, because the gap between “who they are now” and “what they’d have to become” feels too wide.

This is why you see cynical, bitter attendings in some high‑pay specialties. The regret is less “I chose the wrong thing at 26” and more “I built a life so specialized I don’t know how to step away.”

What the Happiest High-Earning Attendings Did Differently

Let me give you the flip side, because it’s not all doom. There are surgeons, cardiologists, GI docs, anesthesiologists, EM and IR folks who are genuinely content 10–20 years out. They exist. I’ve worked with them.

They usually did a few things differently — things your advisors rarely talk about.

First, they were brutally honest with themselves about what they actually enjoy. Not what sounded impressive. Not what their mentors loved. They noticed: “I like clinic more than call,” or “I get energy from complex procedures,” or “I hate being interrupted.”

Second, they chose practice settings as carefully as they chose specialties. This is a big one. Some of the most miserable high‑earners I know picked a specialty for the right reasons and then signed with the wrong group. Toxic culture, insane call, bait‑and‑switch on partnership. Then they felt trapped.

The happiest ones negotiated hard for:

- Reasonable call (or buy-down options as they aged).

- Protected time for teaching/research/side interests.

- A group culture they’d actually want to sit with at 1 a.m.

Third, they controlled lifestyle creep. Not perfectly, but enough that they had options. They didn’t need every last dollar their specialty could produce, so they could say no more easily — no to endless add‑ons, no to extra call weeks “for the team.”

And finally, they stayed willing to adjust. The happiest neurosurgeon I know dropped his case volume and shifted into more admin and teaching. Took a pay cut intentionally. When I asked him if he regretted it, he said, “I regret waiting five years too long to do it.”

That’s the key difference. Not the specialty alone. The willingness to keep re‑architecting your career instead of becoming a hostage to your past decisions.

How to Use These Regrets While You’re Choosing

You’re not going to fully understand these tradeoffs as a student. You can’t. But you can avoid the most naive mistakes.

Here’s what I’d do if I were you, right now:

Talk to attendings 10–20 years out. Not just the shiny new ones. Ask them three specific questions:

- “What’s the worst part of your week, every week?”

- “If your kid were starting med school, would you recommend your specialty?”

- “What would you have done differently at my stage?”

Ignore nearly everyone who can’t answer those directly.

Then, look at your own temperament without the glamour filter. If you need predictable sleep, deeply value being present for evenings and weekends, and hate chronic background anxiety? Don’t sign up for a specialty where your phone can destroy your night at any second, no matter how high the pay.

If you get bored easily and hate repetitive tasks? Maybe don’t pick the procedural specialty built on sheer volume of relatively simple cases, even if the income curve looks great.

And for the love of whatever you believe in, stop thinking you’ll just “push through and cash out early.” Ask any 50‑year‑old ortho or interventional cardiologist if they feel “done” at 55. Most aren’t. Kids, college, aging parents, divorce settlements, business investments. Life gets expensive and complicated, even at 600k+.

FAQ

1. Are high-paying specialties overall a bad choice?

No. That’s the wrong question. They’re powerful tools with sharp edges. For someone who loves high‑stakes procedures, can tolerate call, and builds a sane practice, ortho, cards, GI, neurosurg, IR, etc. can be incredibly rewarding. The problem is people choosing them primarily for pay and prestige, then discovering their personality doesn’t match the day‑to‑day reality.

2. Is it smarter to just pick a “lifestyle” specialty like derm or rads?

Not automatically. I’ve seen miserable dermatologists running cosmetic mills they hate, and burned‑out radiologists who feel like anonymous RVU machines. If you’re bored or misaligned with the work, cushier hours won’t save you. You’re better off in a “harder” specialty you actually enjoy than in an “easy” one you resent.

3. How much does practice setting really matter compared to specialty?

More than most students realize. A malignant group in a “good” specialty will ruin your life faster than a good group in a “hard” specialty. Call structure, partner expectations, admin support, and culture can swing your quality of life dramatically. Talk to multiple attendings in different settings within the same specialty before deciding it’s heaven or hell.

4. What if I choose wrong — am I stuck forever?

You’re more flexible than you think, especially in your first 5–10 years post‑residency. People switch to different practice models, add or drop procedures, shift to hospitalist roles, admin, industry, informatics, consulting. The real trap is letting lifestyle creep and ego make you feel stuck. If you protect some financial margin and keep your identity a bit broader than “I am my specialty,” you’ll have options when you need them.

Key points, so you don’t miss the forest for the trees:

- High income doesn’t erase chronic call, loss of control, or family strain; attendings regularly say they mispriced that trade.

- The worst regrets come from mismatching personality to day‑to‑day reality, not from picking a specialty that’s “too hard.”

- You can’t out‑earn a bad fit. Choose the work and the life you can stand waking up to in 15 years, then worry about the extra 100–200k later.