Only 27% of interns on large medicine services can correctly list every team and their active patients by midnight on their first solo cross-cover night.

The rest are faking it. Or drowning. Usually both.

Let me walk you through how to be in that minority that actually knows what is going on when you are cross-covering three, four, or five services at 2 a.m.

Why Cross-Cover Feels Impossible (But Is Actually Systematic)

Cross-cover is not hard because medicine is hard. It is hard because the information architecture is garbage if you do not build it yourself.

Interns get crushed on cross-cover for the same predictable reasons:

- They have no mental map of “who is where”

- They treat every page like a brand-new consult

- They do not distinguish between “team brain” and “cross-cover brain”

- They never standardize their notes, lists, or check-ins

I have watched brilliant interns become useless at night because they walk into cross-cover with a Single Giant List of Patients and no concept of services, responsibility zones, or urgency tiers.

So we fix that. Methodically.

Step 1: Build a Service-Level Mental Map (Before the First Page)

You cannot manage what you cannot even name.

You should be able to answer, without opening the EMR:

- Which services am I covering?

- Roughly how many patients does each have?

- Where are they physically located (floors / halls)?

- Who are the “watch closely” patients on each?

If you do not know this by 9 p.m., you are already behind.

Create a Cross-Cover Dashboard, Not a List

Your normal day-team “brain” is patient-centric. Cross-cover needs to be service-centric.

Think of it like this: you are an air traffic controller, not a bedside nurse. Your job is to know which flights exist, which are unstable, and which are about to crash.

Make a simple structure you can replicate nightly.

| Service | Census (approx) | High-Risk Patients | Location Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalist A | 14 | 2 (DKA, new GI bleed) | 6 West, 6 East |

| Hospitalist B | 12 | 1 (new NSTEMI) | 5 South |

| Oncology | 10 | 3 (neutropenic fevers) | 7 North |

| Night Float Admits | variable | 0 at start | ED / floor |

You can keep this in a folded sheet in your pocket or as a structured note in the EMR. The key is that you think in services, not a random stack of names.

Step 2: Pre-Game Handoff Like a Prosecutor, Not a Tourist

Handoff is where most interns miss their chance.

They sit there, nodding, while the day team talks at them. They write a few random notes. Then they walk away with no true sense of risk.

You need to interrogate the handoff.

The Only 5 Things You Must Extract From Handoff

For each service, force the day team to give you these—clearly:

- Sickest 3 patients and what you are actually worried about

- Active “if/then” plans (if fever, if hypotension, if chest pain)

- New admits still in flux (not yet stabilized)

- Unfinished tasks that must be done overnight

- “If this happens, wake me up / call senior” situations

Your script can be blunt:

- “Give me your top three patients you are worried about tonight.”

- “Who is likely to decompensate?”

- “Who has anything pending that might require an action overnight? Cultures, CT scans, troponin trends?”

- “What, specifically, should trigger a call to you or the attending?”

You are trying to surface latent risk. Not just hear the story.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start Handoff |

| Step 2 | List services covered |

| Step 3 | Identify top 3 sick per service |

| Step 4 | Clarify if-then plans |

| Step 5 | Review active tasks |

| Step 6 | Define wake-up criteria |

| Step 7 | Update cross-cover dashboard |

Step 3: The “Four Buckets” Mental Map for Every Page

If you treat every page as a unique snowflake, you will drown.

I group every single cross-cover page into four buckets in my head. Instantly. Before I even stand up.

- Airway / Breathing / Circulation (ABC threat)

- Acute change, probably real (neuro, hemodynamics, new severe pain)

- Symptom management / protocol-based (pain, nausea, insomnia, electrolytes)

- Administrative / nonsense (diet orders, missing labs, “needs bowel regimen”)

This is not just philosophical. It affects how you move and think.

How You Use The Buckets

- Buckets 1 and 2: You go. Right now. Laptop optional.

- Bucket 3: Often can be handled by chart review + targeted order, sometimes call.

- Bucket 4: Batch and clear when you have a 10–15 minute window.

When a nurse calls with “BP 78/42 on a patient with sepsis,” you do not scroll through every lab in the last 48 hours before walking over. You are already in Bucket 1. You go, assess ABCs in person, then refine.

This is where new interns fall apart—they try to “finish the story” in the EMR while the patient is actually unstable.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| ABC Threat | 10 |

| Acute Change | 20 |

| Symptom Management | 45 |

| Administrative | 25 |

Step 4: A Physical Map That Lives in Your Feet

You are not only mapping services and risk. You are mapping geography.

If your cross-cover spans multiple floors or buildings, and you do not have a physical pattern, you will spend half the night in an elevator.

You want a simple default route that your body does almost automatically.

Example: 4-Floor Cross-Cover Pattern

- Start of night: Quick walk-through of locations with highest-risk patients

- Then: Standard loop (e.g., 7 → 6 → 5 → 4) every 1–2 hours, modified by pages

- Always tack on a quick eyeball of any earlier “borderline” patient when passing by

If you get a Bucket 1 or 2 page, you break pattern. But you already know roughly where you are relative to that room.

You will be surprised how much calmer you feel when you know, “I am on 6 West, that page is on 5 South, I can be there in under 3 minutes.”

Step 5: Service-Specific Mental Templates

Cross-covering multiple services is dangerous if you mentally treat them all the same.

They are not the same. Oncology cross-cover is not hospitalist cross-cover, which is not transplant cross-cover.

You need tiny service-specific “mental templates” that load in 2 seconds.

Example Templates

Hospitalist / General Medicine

- High-risk themes: alcohol withdrawal, sepsis, COPD, CHF, GI bleed

- Questions you auto-ask: baseline mental status? code status? last set of vitals? most recent labs?

Oncology

- High-risk themes: neutropenic fever, tumor lysis, bleeding, line infections

- Auto-ask: ANC? platelet count? last chemo? central line? prophylaxis?

Cardiology

- High-risk themes: arrhythmias, ACS, heart failure decompensation, anticoagulation issues

- Auto-ask: rhythm? recent trops? anticoagulation? EF? known ischemia?

You want to be able to hear “Onc nurse from 7 North, patient with 38.5 fever and rigors” and your brain snaps to: “Onc template. I care about neutropenia, lines, MAP, broad-spectrum coverage, cultures x2, lactate, sepsis workup.”

| Service | Auto-Check Labs | Big 3 Overnight Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitalist | CBC, BMP, LFTs | Sepsis, alcohol withdrawal, GI bleed |

| Oncology | ANC, platelets, CMP | Neutropenic fever, TLS, line sepsis |

| Cardiology | Troponin, BNP, Mg/K | Arrhythmia, ACS, flash pulmonary edema |

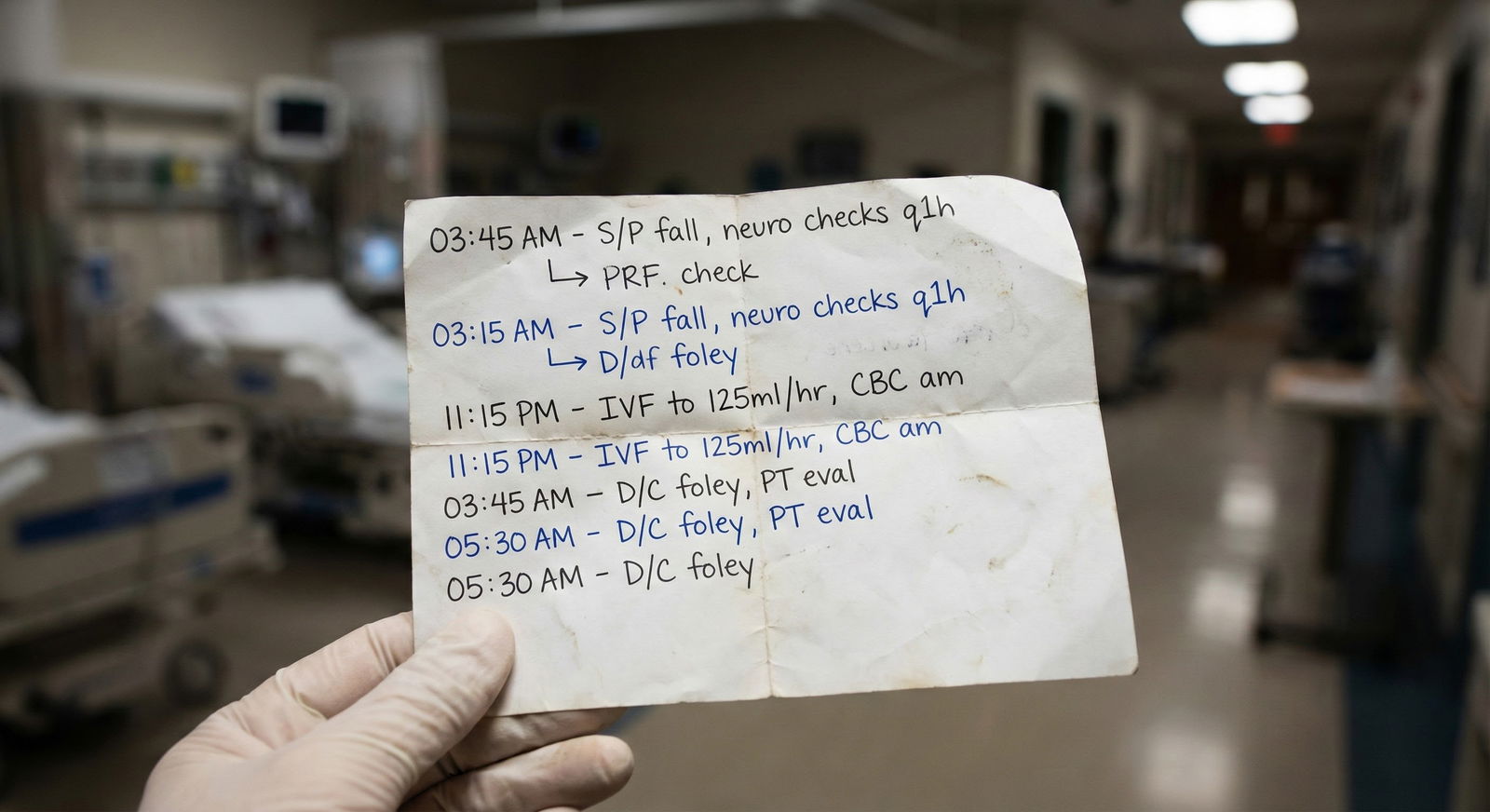

Step 6: What You Write Down (And Why It Matters Later)

Interns underestimate how badly 3 a.m. pages blur together by 7 a.m.

If you do not have a minimal documentation method that works for your brain, you will:

- Forget to follow up on that lactate you ordered

- Miss that 2 a.m. borderline BP is now 3 sequential low BPs

- Struggle to explain to the attending “what happened overnight”

You do not need a novel. You do need a system.

The 3-Line Cross-Cover Note

For any non-trivial issue (Buckets 1–3), I like a tiny note in your personal log or a quick EMR sticky (depending on your hospital rules):

- Time + trigger: “01:45 – page for BP 82/50”

- Assessment: “Alert, warm, lactate pending, no chest pain, exam suggests hypovolemia”

- Action + plan: “250–500 cc LR bolus, repeat BP q15, call if MAP <60; sign-out to day team to reassess”

This does three things:

- Protects you medicolegally

- Lets you check back intelligently

- Gives you content for morning sign-out that is not “Uh… I think they were okay?”

Step 7: A Triage Algorithm You Can Run Half-Asleep

You need a mental script for each page so you do not reinvent your approach every time.

Here is a simple, scalable triage flow.

Answer page. Ask the nurse 3 things immediately:

- “What is the room and service?”

- “What exactly prompted the call?” (vital, symptom, lab, monitor)

- “How does the patient look to you right now?”

While they talk, you silently classify bucket (1–4) in your head.

Before hanging up, commit to one of three responses:

- “I am coming now.” (1–2)

- “Let me review the chart, I will call you back in 5–10 minutes.” (3)

- “This is safe to batch—will address within the hour.” (4)

Open chart, but with purpose: confirm identity, last note, vitals trend, recent labs, code status, and any recent major events.

If your hospital allows, build an EMR SmartPhrase shortcut for your own eyeballing: something like .CROSSCHECK that expands to:

- ID / Code

- Last vitals trend

- Recent labs / imaging

- Last attending note summary

You are not doing full H&Ps. You are doing rapid risk profiling.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Page received |

| Step 2 | Ask nurse key questions |

| Step 3 | Assign bucket 1 to 4 |

| Step 4 | Go to bedside now |

| Step 5 | Review chart first |

| Step 6 | Phone orders and monitor |

| Step 7 | Document brief note |

| Step 8 | Bucket 1 or 2 |

| Step 9 | Needs in person exam |

Step 8: Managing Cognitive Load Across Multiple Services

The real game is not “can you answer this page.” It is “can you answer this page without losing the entire rest of your mental structure.”

You are maintaining:

- A mental census of multiple services

- A prioritized risk list

- A moving queue of pages and follow-ups

- Your admit/consult obligations

You need to offload as much of this from your brain to paper or screen as possible.

One Page, One View

My firm rule: one physical (or digital) sheet that contains all active cross-cover tasks, arranged by:

- Service → Patient → Task → Time / follow-up

Not five different scraps. Not “it’s all in my head.”

You want to be able to glance down and see:

- These three things must happen in the next 30 minutes

- These two patients need a reassessment before sign-out

- These five admin issues can wait

This is your external working memory.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Patient data recall | 25 |

| Task tracking | 30 |

| Navigation/time | 15 |

| Clinical decision-making | 30 |

Step 9: How to Cross-Cover When Things Actually Go Sideways

It is 2:30 a.m. You are cross-covering four services. At the same time:

- You get a rapid response for hypotension on 6 West

- A nurse calls you for active chest pain on 5 South

- Labs show critical K of 6.5 on an oncology patient

This is where your mental map is either your lifeline or your death sentence.

What You Do

Categorize worst-first, not first-come:

- Hypotension with RRT: Bucket 1

- Active chest pain: Bucket 2 (possibly 1 depending on details)

- K 6.5: Bucket 2 but can sometimes tolerate a short delay if stable and no EKG changes

Say this out loud, to yourself if needed:

- “I am going to the RRT now. Notify charge nurse that I will need help with the chest pain page and will call back in 5 minutes.”

- “Ask the chest pain nurse to get stat EKG and vitals while I am at the rapid.”

- “Open the K=6.5 chart as soon as the RRT has a second; call nurse to put patient on monitor and recheck vitals.”

You are not panicking. You are stacking tasks based on mortality risk in the next 10–20 minutes.

And because you have a mental map of:

- Which service each patient is on

- Where they are located

- What their baseline risk is

You can intelligently allocate your time instead of flailing.

Step 10: Handoff Back to Day Team Without Sounding Clueless

Your mental map has one last job: make you sound like you actually knew what was going on all night.

Morning handoff is where attendings silently decide whether you are solid or dangerous.

Do this well:

- Start with service → then patients.

- Focus on changes, not a recap of their entire medical history.

- Highlight any patient who moved “up a level” in risk overnight.

Example:

“Hospitalist A service: three notable events.

Room 623, Ms. Lopez – sepsis from pneumonia, MAPs drifted into low 60s around 1:30, I gave two 500 cc LR boluses, lactate 3.2 trending down to 2.4, still on 2L NC, stable now but I would re-evaluate need for higher level of care if her MAPs fall again.

Room 618, Mr. Patel – new Afib with RVR, HR 150s, started on IV metoprolol per your if-then plan, rate now 90–110. Echo is still pending this morning.

On Oncology, room 710, Ms. Wu – neutropenic fever to 38.9, pancultured, started cefepime, lactate normal, soft but stable hemodynamics; she should be on your sick radar today.”

That sounds like someone who had an organized mental picture. Not someone who just “put out fires.”

Common Failure Modes (And How To Rapid-Fix Them)

I see the same screw-ups every July.

The “Everything is Urgent” Intern

- Problem: runs to every page; no triage.

- Fix: force yourself to classify every page into the 4 buckets before moving.

The “Spreadsheet But No Priorities” Intern

- Problem: beautiful lists; no sense of which three things matter right now.

- Fix: star or highlight the top 3 ongoing risks for each service at all times.

The “EMR Deep Dive Before Leaving Chair” Intern

- Problem: over-review charts while patients are unstable.

- Fix: commit to: if ABC issue or significant vital sign derangement → walk first, then chart.

The “No Service Mental Templates” Intern

- Problem: treats neutropenic fever like regular pneumonia.

- Fix: build 1-line “what scares me most” blurbs for each service you cross-cover.

The “No Notes, No Memory” Intern

- Problem: cannot summarize night; misses follow-ups.

- Fix: use the 3-line cross-cover note for any clinically meaningful event.

Putting It All Together: What a Good Cross-Cover Night Actually Looks Like

Let me sketch a realistic, functional night for a PGY-1 cross-covering three medicine services.

- 7:00 p.m. – Arrive early, update your cross-cover dashboard with services, rough census, and locations.

- 7:15–7:45 p.m. – Aggressive handoff: identify sickest patients, active plans, unfinished tasks. Mark 2–3 “watch closely” patients per service.

- 8:00 p.m. – Quick physical walk to eyeball the highest-risk ones. Introduce yourself to at least one charge nurse.

- 9:00 p.m.–1:00 a.m. – Normal chaos: you triage pages with the 4-bucket model, keep one active task sheet, and batch non-urgent admin pages. Quick 3-line notes for real events.

- 1:00–2:00 a.m. – Natural lull: review labs you ordered earlier, check in on “borderline” patients, clear backlog of non-urgent requests.

- 2:00–5:00 a.m. – Second wave of instability; you protect your mental map by constantly updating: who is now sickest, who moved up a tier in risk, which follow-ups are pending.

- 5:30–6:30 a.m. – Start cleaning up: resolve as many loose ends as you safely can, prepare focused handoff stories for 3–6 key patients.

- 7:00 a.m. – Handoff back to day team, service by service, with crisp overnight changes.

Does that mean nothing will blindside you? No. Cross-cover is inherently messy. But with a clear mental map, the mess does not own you.

You own it.

With these structures in your head and on paper, you are ready to survive your first real cross-cover month. The next step is learning how to balance this with your daytime responsibilities and not burn out in the process. But that is a different problem.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. How detailed should my cross-cover notes be in the EMR versus my personal list?

EMR notes should be minimal but defensible: clear trigger, your assessment, and what you did. Two to three sentences is often enough. Your personal list can hold extra nuance: why you think the patient is borderline, who you are worried about, what to re-check before sign-out. If you are documenting more than 1–2 minutes per event, you are overshooting for most routine issues.

2. What if I disagree with the day team’s “sick list” after seeing the patients?

Trust your own eyes. If you examine a “supposedly stable” patient and your gut says they are higher risk, elevate them on your own mental priority list. Flag them in your dashboard. You do not need permission to be more cautious, but you should communicate that concern in the morning: “I know she seemed okay earlier, but her work of breathing and vitals at 2 a.m. worried me.”

3. How much should I rely on “if/then” plans from day teams?

Heavily, but not blindly. If the plan says, “If BP <90, give 500 cc bolus,” and you find a cold, mottled, altered patient with BP 78/40, the right move is not just hanging fluids and walking away. Use the if/then as a starting point, then apply judgment. If the situation looks worse than what that plan assumed, escalate—call your senior, consider higher level of care.

4. What do I do when nurses disagree with my triage decisions or want me to come “right now” for everything?

Be respectful but firm. Explain your prioritization: “I hear you, and I am coming. Right now I am at a rapid response for a patient whose blood pressure is dangerously low. As soon as that is stabilized, you are next.” Over time, if you respond quickly to real emergencies and reliably follow through, trust improves. Chronic dismissiveness destroys that; consistent transparency builds it.

5. How do I practice building this mental map before I am actually on solo cross-cover?

During earlier rotations, pretend you are the cross-cover. At 5–6 p.m., make your own service-level list: who is sickest, what could go wrong overnight, what active if/then plans exist. Walk through the unit and ask yourself, “If I got called on this person at 2 a.m., what would worry me?” Also, watch your seniors at night. Pay attention not just to what they do clinically, but how they track information and decide where to go next.