The way you end your day as an intern will make or break the next one. Most interns wing it. That is a mistake.

This is your 30‑minute, end‑of‑day routine. Tight. Predictable. Non‑negotiable. Follow it and you will be less scattered, miss fewer things, and walk in tomorrow already ahead.

We are going minute by minute.

Overview: Your 30-Minute Evening Timeline

At this point you should stop “just logging out” and start running a checklist.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Wrap Up Work - 0-5 min | Hard stop and quick reset |

| Wrap Up Work - 5-15 min | Close the chart loop |

| Handoff and Planning - 15-20 min | Tighten sign-out and handoffs |

| Handoff and Planning - 20-25 min | Prepare tomorrow |

| Personal Reset - 25-30 min | Decompress and detach |

Here is the structure we will use:

- Minutes 0–5: Hard Stop & Quick Reset

- Minutes 5–15: Close the Patient Care Loop

- Minutes 15–20: Upgrade Your Handoffs

- Minutes 20–25: Set Up Tomorrow

- Minutes 25–30: Personal Decompression

You can do this standing at the workstation, at a quiet corner table, or in your call room. But you do all of it. Every day.

Minutes 0–5: Hard Stop & Quick Reset

At this point in the day, you want to stop the “one more thing” spiral.

0–1 minute: Call the hard stop

- Say it out loud in your head: “End-of-day routine starts now.”

- Physically sit down if you have been running around.

- Silence non-urgent notifications for 30 minutes (phone, watch).

This is a mental switch. You are no longer “chasing tasks.” You are closing the loop on the day.

1–3 minutes: Rapid brain dump

Open a blank note (paper or app). Then, without editing, write:

- All patients you touched today (admitted, rounded on, consulted).

- Any unresolved worries (“follow up blood culture”, “family upset”, “question about anticoagulation dose”).

- Any “I should learn this” topics.

Do not organize yet. Just dump.

3–5 minutes: Sort into three buckets

Take that messy list and mark each item:

- “T” = Task that must be completed before leaving.

- “H” = Handoff item for night team.

- “L” = Learning or later item (can wait until after shift or tomorrow).

If anything has no letter, either delete it or decide the category. This two-minute sort will save you from walking out and then remembering the one thing you forgot in the parking lot.

Minutes 5–15: Close the Patient Care Loop

At this point you should be thinking, “If I got hit by a bus on the way home, would someone else know what is going on with my patients?”

This 10-minute block is about charts and plans. Nothing glamorous. Extremely high yield.

5–10 minutes: The Documentation Sweep

Pull up your list of patients from today. One by one.

For each patient, ask:

Is there a clear note for today?

- Admission? Progress? Post-op? Brief consult?

- If not, create a focused, not-perfect note.

- At least include: diagnosis, current status, today’s key change, and plan.

Are critical results documented or acknowledged?

- New troponin? CT finding? Positive culture?

- Make sure it is in your note or a quick addendum: “CT chest: no PE, stable infiltrate; will continue current abx.”

Would the on-call team understand the plan from the chart alone?

- If not, add 1–2 sentences under “Plan” that spell it out:

- “Hypotension improved with 1L LR, MAP now >65, no pressors. If MAP <60, give additional 500 mL LR and page night float.”

- If not, add 1–2 sentences under “Plan” that spell it out:

Target time per patient: 30–60 seconds. You are not rewriting your notes. You are making them safe and legible.

10–15 minutes: Meds, Orders, and “Landmines”

Now you check for the stuff that comes back to bite interns at 2 a.m.—even when you are not on call.

For every patient on your list:

Med reconciliation sanity check

- Any obviously wrong home med list? (The “metoprolol 200 mg TID” that is actually 25 mg BID.)

- Any antibiotics or anticoagulants that need re-timing, narrowing, or stop dates?

Timers and expiring orders

- Foley / central lines without indications?

- “Telemetry” with no longer needed indication?

- Restraints orders expiring without follow-up?

Bad surprise prevention

- Any borderline vitals before you leave?

- If yes:

- Re-examine briefly if you can.

- Clarify parameters in the chart and in sign-out.

- Tell the nurse what to watch for.

- If yes:

- Any borderline vitals before you leave?

This is where you prevent the “why was nothing done?” attending rant on rounds tomorrow.

Minutes 15–20: Upgrade Your Handoffs

At this point, you should have a basically accurate chart. Now you build a clean handoff.

I have seen disastrous sign-outs. Walls of text. Old problems. No priorities. Do not be that intern.

| Handoff Element | Poor Version | Strong Version |

|---|---|---|

| ID + Situation | "65 M w/ pneumonia" | "65 M, CAP, day 2, stable on 2L NC" |

| Primary Concern | Not mentioned | "Big thing: labile BP after diuresis" |

| Overnight Tasks | Buried in narrative | Bullet list with clear if/then instructions |

| Code/Goals of Care | Missing or outdated | Explicit code status + any recent discussions |

| Anticipated Problems | None listed | "Watch for EtOH withdrawal, CIWA climbing" |

15–18 minutes: Create or clean your sign-out list

Use whatever your program uses: EHR list, Excel, sign-out tool.

For each patient, update:

- 1-line ID + reason for admission

- Hospital day or post-op day

- Today’s major change(s) (one line)

- Active problems needing attention overnight

- Code status and any limitations

Delete dead weight. If a problem is resolved, remove it. Old sign-out clutter is how night float misses what matters.

18–20 minutes: Add concrete “if/then” instructions

This is where you show respect for the night team.

For every active issue:

- “If SBP <90, repeat BP manually, give 500 mL LR, if no improvement page cross-cover.”

- “If new chest pain, EKG and troponin, page on-call resident before calling cardiology.”

- “If fever >38.5, collect blood cultures and UA, give Tylenol, page cross-cover.”

You are not writing a novel. You are writing a checklist for future-you’s colleague at 3 a.m.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Weak Handoff | 18 |

| Strong Handoff | 11 |

Minutes 20–25: Set Up Tomorrow

At this point, you should not be “hoping” tomorrow goes well. You should be architecting it.

This 5-minute block turns tomorrow’s chaos into something survivable.

20–23 minutes: Build your morning list

Look at tomorrow’s census and plan like a chess game, not whack-a-mole.

- Mark new admissions you will need to see fully.

- Mark high-risk patients:

- ICU transfers

- Recent rapid responses

- Post-op day 0–1

- Sick but “floor appropriate” patients on pressors yesterday or with unstable vitals.

Then, roughly sequence your morning:

- Who gets seen first?

- Which labs or imaging need to be checked before you walk into the room?

- Any family meetings scheduled?

Jot a simple order, something like:

- Check labs/imaging for [list of rooms].

- See: Room X (sickest), then Y, then Z.

- Write note templates or skeletons for high-complexity patients.

23–25 minutes: Tiny prep that has a big payoff

This is where you do 1–2 micro-actions that save 15 minutes tomorrow:

Examples:

- Pre-create skeleton notes in the EHR for complex patients (headers and problem list only).

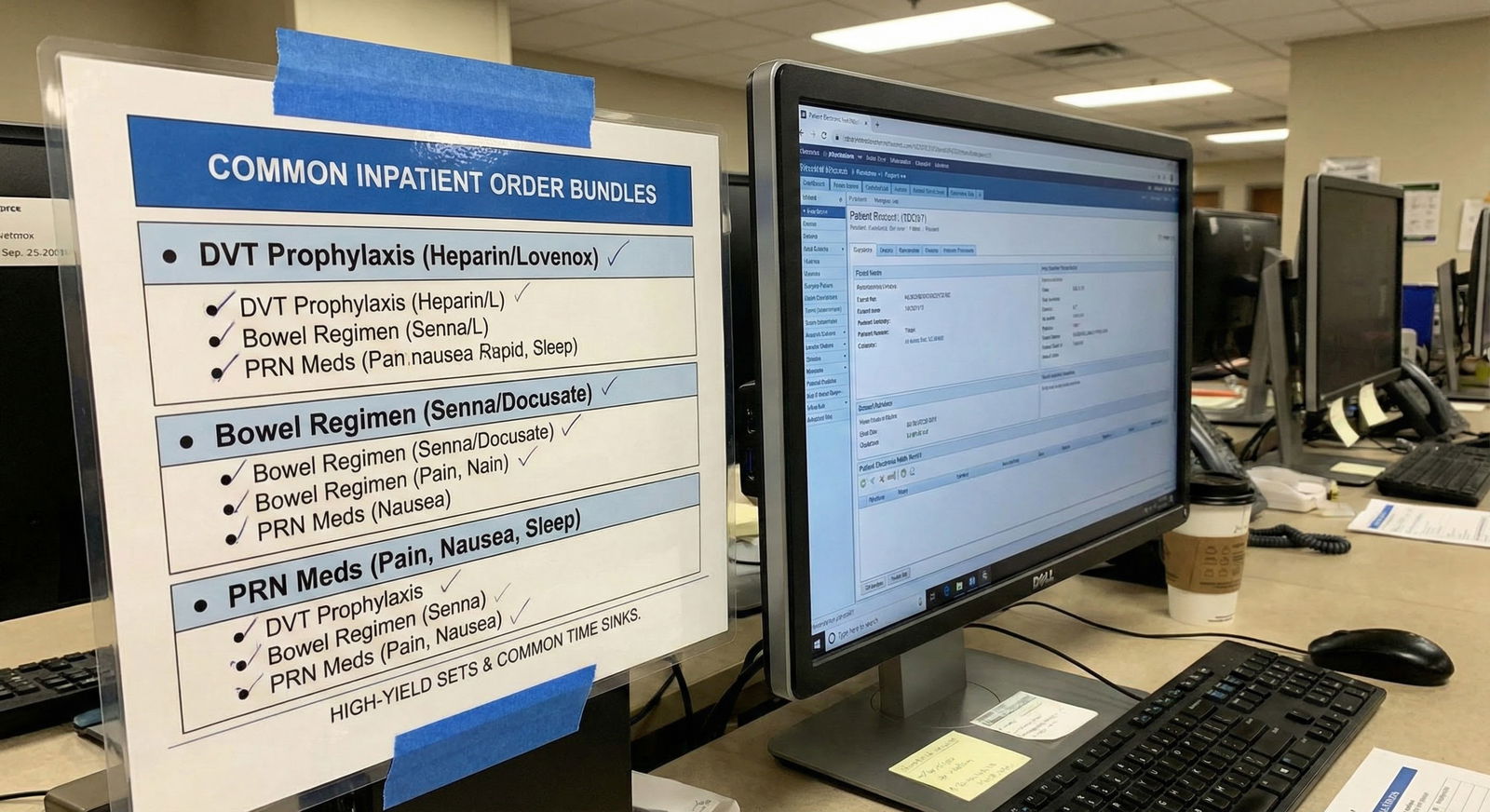

- Draft 1–2 order sets you know you will need (e.g., for diuresis, ABG, sepsis bundle).

- Send yourself a short message: “Look up DKA insulin protocol before rounds” or “Review management of upper GI bleed.”

Two to three minutes now prevents the 6:45 a.m. panic brain freeze.

Minutes 25–30: Personal Decompression & Detach

If you blow off this part, you will pay for it in burnout by October. The interns who last know how to end the day on purpose.

25–28 minutes: Quick reflection and boundary

You do not need a gratitude journal. You need 2–3 honest sentences.

On your same note from earlier, add:

One thing you handled well

- “Explained code status clearly.”

- “Recognized early sepsis and escalated quickly.”

One thing to improve tomorrow

- “Call consults earlier in the day.”

- “Check vitals myself before signing out a borderline patient.”

Then, one rule: once you leave the hospital, you are done actively reviewing charts unless on call.

Say to yourself (yes, literally if needed): “I have done what I can for today. The night team has it now.”

28–30 minutes: Light mental off-ramp

You are not going to magically “leave work at work.” But you can give your brain a ramp instead of a cliff.

Pick one small ritual that signals “workday over”:

- Put your stethoscope in the same pocket of your bag, every day.

- Walk one loop outside the hospital before getting in the car.

- Put on a specific “commute home” playlist or podcast that is not medical.

Last 30 seconds: check that you have your badge, keys, phone, and wallet. Lock your locker. Physically walk away.

Putting It All Together: A One-Page Evening Checklist

Use this as a template for your own printed card or phone note.

| Time Block | Key Actions |

|---|---|

| 0–5 min | Hard stop, brain dump, label T/H/L |

| 5–10 min | Ensure notes exist, document key results |

| 10–15 min | Check meds, orders, vitals, prevent landmines |

| 15–18 min | Update sign-out: ID, problems, today’s changes |

| 18–20 min | Add clear overnight if/then instructions |

| 20–23 min | Plan morning: priority patients and order |

| 23–25 min | Micro-prep: skeleton notes, reminders |

| 25–28 min | Reflect: 1 win, 1 improvement, set boundary |

| 28–30 min | End-of-day ritual, gather items, leave |

If you want to track yourself, you can even log how often you actually complete all 30 minutes versus rushing out.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Week 1 | 40 |

| Week 2 | 55 |

| Week 3 | 70 |

| Week 4 | 80 |

The goal is not perfection. The goal is steadily increasing the percentage of days where you end on purpose instead of by exhaustion.

How This Looks in Real Life: A Sample Evening

You just finished a brutal ward day. It is 6:35 p.m. You are tired, hungry, and your co-intern is already halfway to the parking garage.

Here is what “doing this right” looks like:

6:35–6:40 p.m.

You sit down, start your 30-minute timer. Brain dump: “New GI bleed in 712, follow up GI recs; Mrs. L family wants update; look up hyponatremia.” Mark T/H/L.6:40–6:50 p.m.

You rapid-review each patient. Realize one progress note is missing; you write a concise note. You add “troponins downtrending, less concerned for ACS, ongoing observation” to another note. You see a Foley with no indication; you place a removal order for the morning with parameters.6:50–6:55 p.m.

You clean up sign-out, delete three “resolved” problems, update code status for one patient after today’s family meeting, and write specific night instructions for the GI bleed patient.6:55–7:00 p.m.

You mark your sickest three patients for early-morning check. You open skeleton notes for the two most complex ones. You type “Review GI bleed resuscitation” into your phone for later.7:00–7:05 p.m.

You jot “Handled RRT calmly” and “Tomorrow: check labs before rounds” in your note, close the laptop, put your stethoscope in your bag, put in your earbuds, and walk a slow lap outside before heading to your car.

You get home tired. But not frantic. You know you did what an actual physician does: closed the loop, protected your patients, and protected yourself.

Final Thoughts

Three things to remember:

- The day is not over when the last order is placed. The day is over when you have closed the loop: charts, handoffs, and your own head.

- A 30-minute end-of-day routine will save you hours of chaos, reputation damage, and self-doubt later. Interns who seem “naturally organized” usually just do this stuff on purpose.

- Treat this as non-negotiable professional hygiene. Like washing your hands. You will make fewer mistakes, learn faster, and walk into tomorrow already ahead.