Got assigned to the rotation everyone whispers about with that half-laugh, half-pity tone — “Oof… good luck, you’ll see”?

Here is how you survive it without torching your health, your relationships, or your reputation.

1. First 48 Hours: What You Do Right Now

The worst way to enter a brutal block is “wait and see.” By the time you “see,” you’re already underwater.

In the 48 hours before you start, do this:

A. Get Intel From People Who Just Finished

You do not want generic “you’ll be fine” reassurance. You want specifics.

Text or message 2–3 seniors or co-interns who finished that exact block in the last 3–6 months. Ask very direct questions:

- “What actually makes this rotation brutal? Hours? Personalities? Scut?”

- “What time did you usually get in and out on call / non-call days?”

- “Who are the key people I should not piss off?”

- “What’s one thing you wish you had started doing on day 1?”

- “What can I safely not care about on this rotation?”

You’re looking for patterns. If three people mention the same attending, the same sign-out bottleneck, or the same 5 pm disaster moment – believe them.

B. Build a Minimal Survival Kit

No, not a cute “what’s in my call bag” Instagram spread. A real one that assumes you will not get to sit or eat when you want.

Bare minimum, prep:

- 2–3 pocket snacks per shift that survive in your pocket: nuts, bars, jerky. No wrappers that sound like a jet engine at 2 am.

- 1 big water bottle that does not leak when thrown in a backpack.

- Backup phone charger and a wall brick that lives in your white coat or bag.

- A small notebook or folded paper “brain” + 2 pens that you like. You’ll write more when you’re stressed.

Then set up one thing at home: a “drop zone” near your door with a hook for your bag and a place to dump your pockets. On brutal blocks, decision fatigue is real. Make coming and going frictionless.

2. Understand What “Brutal” Actually Means On Your Block

“Brutal” is not a diagnosis. It’s a symptom. You need to know what you’re actually treating.

Most notoriously bad rotations are some blend of these:

| Main Problem Type | How It Usually Feels | Primary Survival Tactic |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | Endless pages, admits, tasks | Ruthless task triage + templates |

| Personalities | Yelling, humiliation, nitpicking | Scripted communication + boundaries |

| Systems Chaos | Lost orders, delays, no structure | Create your own micro-systems |

| Hours / Schedule | String of 28h calls, no days off | Sleep protection and automation |

| Emotional Load | Constant death, codes, bad news | Compartment + planned decompression |

Ask those recent grads of the rotation: “If you had to pick ONE: is this block brutal because of volume, personalities, system chaos, hours, or emotional weight?” Their answer tells you where to spend your energy.

3. Day 1–3: Set the Tone (Without Being a Doormat)

Your first few days matter more than day 14. People quickly decide whether you’re “solid” or “a mess.” You want “solid and improving.”

A. Show Up Early — But With a Plan

For the first week, come in 30–45 minutes earlier than you think you need. Not just to “work harder,” but to:

- Skim all your patients, vitals, and overnight events.

- Pre-write or at least outline your notes on the sickest few.

- Pre-call that one consultant you know will be slow.

That buffer is your “learning tax.” Once you’re efficient, you can pull it back.

B. Say This Script to Your Senior on Day 1

Do not try to impress with jargon. Try this instead:

“Hey, I know this block has a rep for being tough. I work hard and I’m pretty organized, but I’m new to this service. My priority is not dropping balls. If I start missing something or doing something inefficiently, I’d like you to tell me early so I can fix it. How do you like things run on this team?”

You’ve just done three things:

- Signaled you know it’s hard and you’re not naive.

- Given them explicit permission to correct you (which reduces passive-aggressive blowups later).

- Asked a concrete question that forces them to articulate expectations.

Pay attention to what they say about:

- Timing (what time they want notes done, discharges out, consults called)

- Communication style (text vs page vs call)

- Pet peeves (this matters more than you think)

Write their answers down. If the senior says, “I want all discharges out by 10,” that’s now law unless an attending overrides it.

4. Task Triage: How Not To Drown in Work

On a brutal block, the main challenge is rarely “I don’t know what to do.” It’s “I know 20 things to do and there’s no way I can do them all fast enough.”

You need a ruthless, simple triage system.

A. Use a 4-Box System On Your Patient List

On the back of your list or in a notebook, divide a page into four quadrants and quickly sort tasks:

- Critical + Urgent (now or someone might die/get harmed)

- New chest pain, hypotension, sepsis, acute mental status changes, transfusion orders for Hgb <6 with symptoms.

- Important + Time-Sensitive (today before 5 pm)

- Discharge orders, key consults, imaging that changes management today.

- Important + Can Wait (tonight or tomorrow)

- Med rec cleanup, non-urgent med adjustments, social work clarifications.

- Low Value / Optional

- Perfectly reformatting every note, re-ordering a PRN med that has 7 equivalents already.

When five pages hit at once, you literally glance at your scribbles and choose a quadrant 1 or 2 task. That’s it. Stop trying to “keep everything in your head.” You will fail when you’re sleep-deprived.

B. Timebox Your Notes

Brutal blocks punish perfectionism.

Give yourself limits:

- Max 5–7 minutes on a stable progress note.

- Max 15–20 minutes on a new admit H&P (once basic workup is set).

If you’re blowing those numbers consistently, your template sucks or you’re over-writing. Ask a strong co-intern or senior for their template and steal it shamelessly.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Direct Patient Care | 30 |

| Documentation | 25 |

| Pages/Calls | 20 |

| Walking/Searching | 15 |

| Other | 10 |

Your goal is to shrink “Documentation” and “Walking/Searching,” not by cutting corners on care, but by using better systems.

5. Handling Difficult Personalities Without Getting Crushed

On some rotations, the pathology isn’t on the ward. It’s at the workroom desk.

A. The Screaming Attending

I’ve seen this: an attending berating an intern at the nursing station because a CT was delayed. Everybody hears. Everybody pretends not to.

Do this in the moment:

- Keep your voice level and neutral.

- Stick to facts, not feelings.

- Don’t explain for 2 minutes; give a 2–sentence status update.

Example:

“I ordered the CT at 09:15 and called radiology at 10:00 when it hadn’t been picked up. They said transport was backed up but it’s flagged as urgent. I’ll call them again now and update you.”

Later, when the dust settles, you decide whether this is “annoying” or “unsafe/abusive.” If it’s truly abusive and repetitive, talk to your chief resident or program leadership, not just your group chat. You’re not obligated to be a punching bag.

B. The Nitpicky Senior

The senior who rewrites your note, criticizes your presentations, and sighs at everything. Annoying, but survivable.

Your move: depersonalize and weaponize them as a resource.

“Can you show me one of your notes/presentations so I can match your style? I want to stop doing X the way you don’t like it.”

You’re basically saying: hand me the answer key. Many of them will. And once you adapt, they usually back off.

C. Nurses and Consultants When Everyone Is Fried

Do not fight nurses or consultants on a brutal block unless it’s about patient safety.

Make your default line:

“Help me understand what you’re worried about so I can work with you on this.”

Sometimes, the nurse is right and you missed something. Sometimes, the consultant is stalling and you just need to document: “Cardiology paged at 13:05, awaiting eval.”

You’re not there to win arguments. You’re there to move care forward and protect yourself legally.

6. Systems Hacks: Make the Rotation Work For You

Brutal blocks expose every crack in the system. You cannot fix the hospital. You can, however, build tiny, personal systems that save you hours over a month.

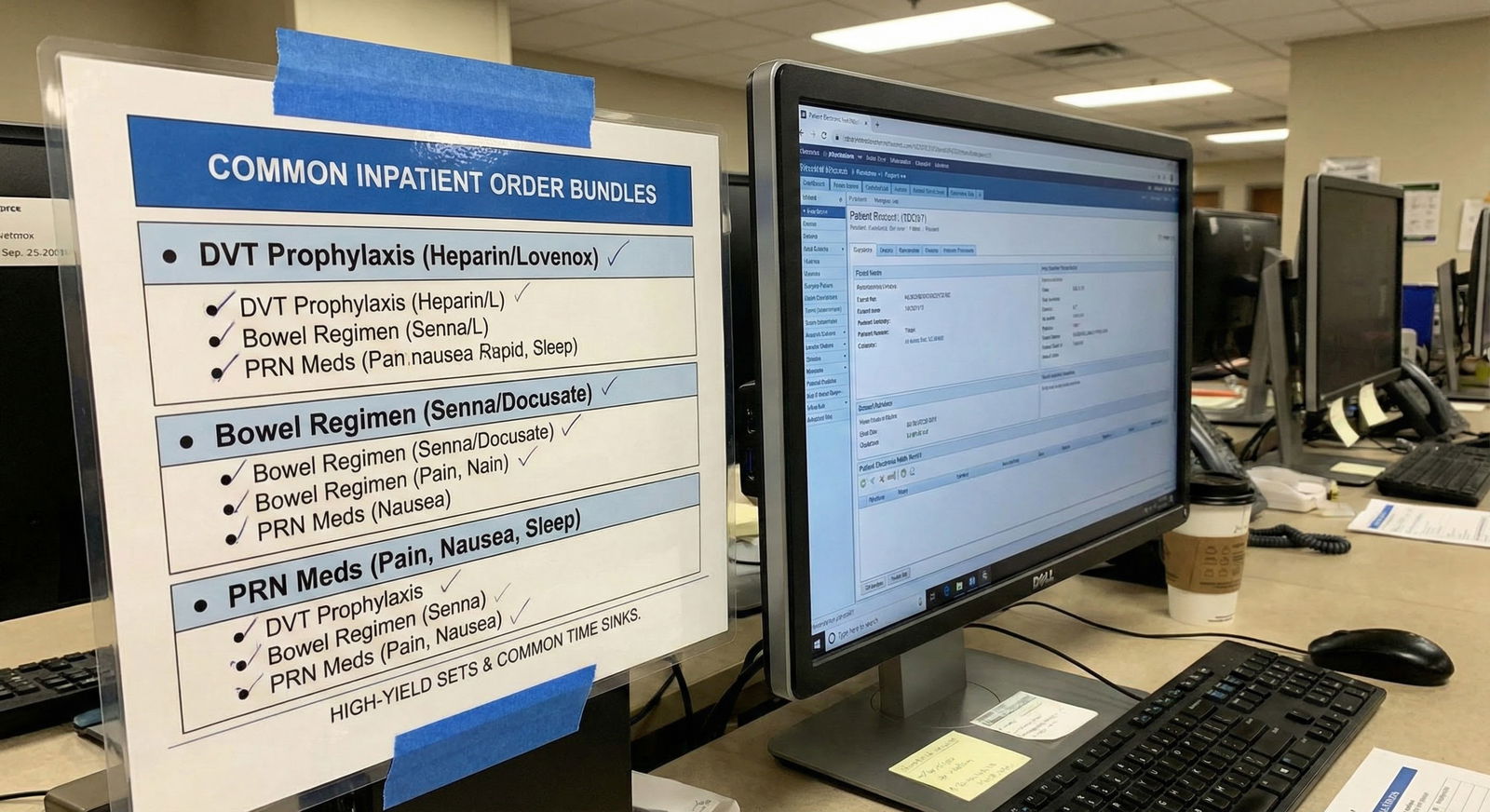

A. Build Reusable Order Sets / Note Snippets

You know you’ll see:

- Sepsis bundle.

- DKA.

- CHF exacerbation.

- COPD exacerbation.

- Post-op fever.

Create smartphrases or note chunks for these. Example for CHF admit:

- Pre-loaded with: daily weights, I/O, low sodium diet, BNP, EKG, echo check, tele, diuresis plan, electrolyte checks.

You shouldn’t be reinventing this plan at 3 am. Click, edit, done.

B. Make a Pre-Rounding Route

Do not pre-round like a Roomba. Have a route.

Example on a heavy medicine service:

- Sickest/ICU step-down patients first (in person).

- Patients likely to discharge that day (check vital signs, new labs, see if they’re truly ready).

- New admits overnight that are unclear.

- Chronic stable patients last.

This way, if rounds start early or you get interrupted, at least the sick and leaving patients are handled.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Arrive Early |

| Step 2 | Check Overnight Events |

| Step 3 | Prioritize Sickest Patients |

| Step 4 | Identify Likely Discharges |

| Step 5 | Outline Notes for Top Priority |

| Step 6 | Touch Base With Senior |

| Step 7 | Team Rounds |

That’s your skeleton. Days will still blow up, but at least the bones are right.

7. Protecting Your Body and Brain (Without Magical Self-Care Nonsense)

You’re not going to yoga 3 times a week on a malignant ICU month. Let’s be honest.

So think in terms of “micro-protection,” not “self-care.”

A. Sleep Like It’s a Procedure

Treat sleep as a medical intervention. Protocol-ize it.

On brutal blocks, you often have only 2 choices: 1) mindless phone scrolling until 1 am or 2) unconsciousness.

Force a ritual:

- Phone physically across the room or in another one for sleep periods.

- 10–15 minute wind-down non-screen activity: shower, read junk fiction, meditate if that’s your thing.

- Earplugs and eye mask if you sleep days post-call.

If you’re post-call and thinking “I’ll just watch something for 20 minutes,” stop. That is your brain lying to you. Go horizontal, lights off. Your body will do the rest.

B. Non-Negotiable Fuel

Set one non-negotiable: you will ingest real calories 1–2 times per shift, even if standing.

You might not eat “meals,” but you can:

- Slam a yogurt and nuts between pages.

- Eat half a sandwich walking between floors.

- Drink an Ensure if your hospital has them.

This is not about nutrition perfection. It’s about not having your brain running on fumes when you’re making real decisions.

C. One Tiny Daily Reset

Pick ONE thing you can do most days in under 10 minutes that makes you feel like a person:

- 5-minute hot shower where you actually breathe and don’t answer pages.

- 10 pushups and a stretch.

- Journaling one sentence: “Today sucked because ____ but I handled ____.”

It sounds small and stupid. It isn’t. On bad blocks, your brain starts to believe you are only a task-completing machine. You need a daily reminder that you exist outside the hospital.

8. Preserving Your Reputation and Learning Something (Anything)

Your goal is not just to “not die.” It’s to avoid being labeled “weak” or “checked out,” which can haunt you later.

A. Focus on Learning 2–3 Things Really Well

This is not the block where you’ll read two UpToDate articles a day. Accept that.

Instead, decide early: “On this month, I will become solid at X, Y, Z.”

Examples:

- On trauma surgery: initial trauma resuscitation, common post-op complications, basic wound care.

- On MICU: vent basics, shock patterns, sedation/analgesia management.

Then, when those things come up in real time, you engage hard. Ask questions at the bedside. Look up that one detail after your shift. Ignore the rest. Harsh, but realistic.

B. Manage Upward: Let Seniors See Your Effort

You do not need to grandstand. You do need to be visible as someone who tries and improves.

Behaviors that matter on brutal blocks:

- Owning your mistakes quickly: “I missed that K result, I’ve re-checked all morning labs now and added a K re-draw.”

- Closing loops: when given a task, you circle back: “Cardiology saw the patient, they’re recommending…”

- Not disappearing: if you step away for 20 minutes, tell someone: “I’m going to the ED to see the new admit; reachable by phone.”

Seniors don’t expect perfection. They expect not to wonder, “Where the hell is my intern?”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Work Ethic | 90 |

| Reliability | 85 |

| Clinical Knowledge | 70 |

| Efficiency | 75 |

| Team Attitude | 80 |

Notice what’s at the top. Early on, they care much more about reliability and effort than encyclopedic knowledge.

9. When You’re Actually Hitting a Wall

There’s “this is exhausting” and there’s “I am not safe anymore.” You need to know the difference.

Red flags you’re moving from hard to dangerous:

- You’re making repeated near-miss errors (wrong patient, wrong dose, almost missed critical lab).

- You’re driving home and don’t remember how you got there.

- You’re crying in the bathroom multiple times a week and can’t stop once you start.

- You’re having thoughts like, “If I got into a minor car accident, at least I’d get a day off.”

If that last one rang too true, you’re not “weak.” You’re cooked.

At that point, you talk to:

- Your chief resident or APD.

- A trusted senior who has some pull.

- If necessary, occupational health / employee assistance.

Say it plainly: “I’m worried I’m no longer safe to practice because of how exhausted/anxious/depressed I am on this rotation.” That language gets attention because it should.

This is not about quitting every hard thing. It’s about not sacrificing yourself on the altar of “looking tough.”

10. Debrief and Bank the Lessons After It’s Over

Rotations like this can quietly damage you or quietly level you up. The difference is whether you process them.

When the block ends and you’ve slept once like a human, take 20–30 minutes and answer these:

- What 3 things did I actually get better at?

- What 3 systems or habits did NOT work for me at all?

- Whose style did I respect, and whose did I never want to emulate?

- What one thing will I do differently on the next tough month?

You’re turning misery into data. You will absolutely see versions of this block again.

And yes, vent to your co-interns. But after the venting, pull at least one concrete change out of it.

FAQ: Brutal Rotation Survival

1. Should I tell my program director that this rotation is malignant?

Not mid-rant on a random Tuesday. Document specific incidents that concern you (unsafe staffing, repeated abuse, blatant duty hour violations). If it’s truly problematic, schedule a brief, focused meeting: “I want to share some specific concerns from my recent X rotation that impact patient safety and trainee well-being.” Concrete examples, not just “it sucked.”

2. How do I study when I barely have time to sleep?

You don’t “study” in the traditional sense. You do just-in-time learning: pick 1–2 key topics per week that you actually saw and spend 10–15 minutes on them on a post-call afternoon or weekend. Use questions (UWorld, AMBOSS) instead of reading chapters. Anything more ambitious will probably fail and make you feel worse.

3. Is it okay to tell my senior I’m overwhelmed?

Yes, but make it actionable. Example: “I’m at the point where I’m worried about missing something. Right now I have these 7 open tasks. Can you help me prioritize what truly must happen in the next hour vs what can wait?” That shows insight and protects patients. Just saying “I’m drowning” with no specifics is less helpful.

4. How do I handle it if I actually make a serious mistake on this block?

Own it fast and specifically: “I missed X / ordered Y incorrectly. Here’s what I’ve already done to fix it and prevent it from happening again.” Expect to feel like garbage for a while; that’s normal. Debrief with someone you trust to separate the system factors from your individual responsibility. Then build a concrete safeguard (a checklist, double-check habit) into your workflow.

5. What if every rotation feels brutal, not just this one?

Then the issue may be bigger than a single block. Ask yourself: is this burnout, depression, anxiety, or a mismatch between your coping skills and the demands of residency? Talk to a mental health professional who understands medical training, and also to a trusted senior or chief. There’s a difference between “this specific ICU month is hell” and “I feel dead inside on clinic days and elective too.” The second one needs attention now, not after graduation.

Open your calendar right now and look at when that brutal block starts. Then text one person who’s just finished it and ask: “What actually makes this rotation brutal, and what’s one thing I should start doing on day 1?”