The usual advice for dealing with moral distress is dangerously incomplete. “Debrief with colleagues.” “Use your EAP.” “Remember you did your best.” That might keep you functioning for another shift. It does not actually defuse what is building inside you.

You are not dealing with generic “stress.” You are dealing with a psychological injury that comes from acting (or being forced to act) against your own moral code. Very different problem. Requires different tools.

Here is the blunt truth: if you do not learn to process moral distress deliberately, it will leak out as burnout, cynicism, compassion fatigue, or that quiet urge to leave medicine altogether. Mindfulness, used correctly, is one of the few tools that can go right to the core of it.

Not “breath app for 3 minutes between patients” mindfulness. Serious, structured mental training that you apply before, during, and after difficult ethical cases.

Let me walk you through exactly how to do that.

1. Know What You Are Fighting: Moral Distress, Not “Stress”

Before you apply any technique, you need a precise diagnosis.

Moral distress is not:

- Being tired after a 28‑hour call.

- Feeling overwhelmed by documentation.

- Having a bad day with an attending.

Moral distress is what hits when:

- You know the ethically appropriate action.

- You cannot take that action because of constraints.

- You feel complicit in causing or allowing harm.

Classic triggers:

- Continuing aggressive care on a patient you believe is being tortured by treatment.

- Withholding a therapy for financial or insurance reasons.

- Being forced to follow a policy that conflicts with your ethical judgment (visitor restrictions, forced discharges, limited resources).

- Watching colleagues disrespect or neglect a patient and feeling powerless to intervene.

- Participating in care that conflicts with your deeply held values (for some, terminations, death penalty evaluations, gender‑affirming care, etc.).

What does it feel like? I have heard the same words over and over from residents and attendings:

- “I feel like I betrayed this patient.”

- “I did what the system wanted, not what I knew was right.”

- “I walked out of that room and felt dirty.”

That is the target. Not generic anxiety. Not sadness. A specific sense of moral violation.

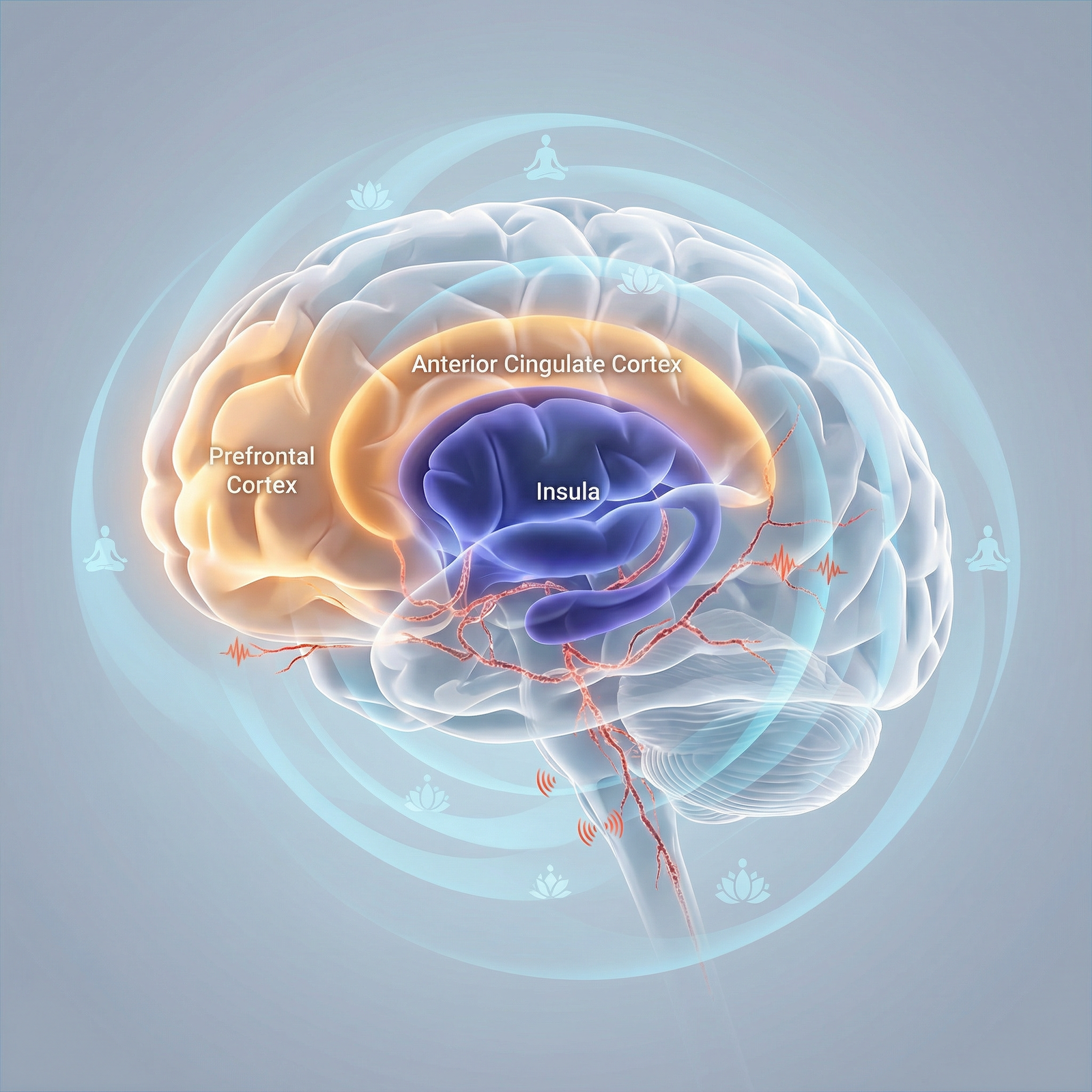

Why mindfulness matters here:

Moral distress has three layers:

- The event (what happened).

- The story (what it means about you as a person).

- The residue (what lingers in your body and nervous system).

You cannot change many events.

You can change the story you attach to them and how your nervous system stores them.

Mindfulness is extremely good at those last two.

So the mission is simple: use mindfulness to interrupt and rewire the story and to discharge the physiological residue.

2. Do Not Start After the Case: Build a Baseline First

You cannot learn to swim during a flood. You need a baseline practice so that, when an ethical disaster hits, you already have the gear.

Goal: 10–15 minutes per day, 5+ days per week, for 6 weeks. This is not spiritual. This is skill acquisition.

Core Daily Practice (10–15 minutes)

Step 1 – Posture and timer (1 minute)

Sit on a chair, feet flat, spine straight but not rigid. Hands resting on thighs. Set a 10–15 minute timer. No music.

Step 2 – Anchored breathing (3–5 minutes)

Focus on one anchor: either the sensation of breath at the nostrils, or the rise/fall of the abdomen.

- Inhale through the nose, exhale through the mouth or nose (whatever is natural).

- Count 1 on the inhale, 2 on the exhale, up to 10. Then start again at 1.

- Thoughts come in. You notice. You return to the breath. No commentary.

You are training one muscle: noticing you are distracted and returning without drama.

Step 3 – Body scan for moral residue (5–7 minutes)

This is the part physicians actually skip. Do not skip it.

- Move your attention slowly from head to toe.

- Notice areas of:

- Tightness (throat, jaw, chest, gut are common).

- Heat or cold.

- Numbness or “armored” feeling.

You are not trying to relax them. That is the mistake. Your job is to feel them fully without fixing.

Example internal script:

“Jaw tight. Burning behind sternum. Knots in stomach. I can stay with this. This is what anger feels like. This is what guilt feels like. It will move if I let it.”

Why this matters: moral distress is not just a thought problem. It is a stored physical state. If you only “reframe your thinking” but never let your nervous system feel and release the sensations, the distress will keep resurfacing.

Step 4 – Labeling practice (1–2 minutes)

Before you end, name the dominant state:

- “Worry.”

- “Guilt.”

- “Anger.”

- “Fear.”

- “Numbness.”

Just one or two words. Soft labels. You are building the habit of seeing the emotion as an object, not as your identity.

You do this every day, not just on bad days. Then, when a brutal case hits, you have familiarity with your internal landscape and a way to move through it.

3. A Protocol for Right After a Difficult Ethical Case

You walk out of ICU Room 12 after withdrawing care over the objections of a divided family. Or you just discharged a patient you know will end up homeless and probably back in the ED.

You feel sick, shaky, angry, or weirdly numb. Here is the protocol I teach residents, attendings, and even nurses.

This takes 5–10 minutes. It fits into real life.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Leave Patient Room |

| Step 2 | Find Private Space |

| Step 3 | Grounding Breath 3x |

| Step 4 | Name the Injury |

| Step 5 | Body Scan 3 minutes |

| Step 6 | Separate Fact From Story |

| Step 7 | Choose Next Wise Action |

| Step 8 | Return to Work |

Step 1 – Get 3–5 minutes of privacy

- Medication room.

- Stairwell.

- Empty consult office.

- Even a bathroom stall if that is all you have.

Do not tell yourself “no time.” You have 3 minutes. You waste more than that scrolling.

Step 2 – Grounding breath: 3 slow cycles

- Inhale through the nose for 4 seconds.

- Hold for 4 seconds.

- Exhale through the mouth for 6 seconds.

Three cycles only. You are not doing a spa session. You are flipping your autonomic state down one notch.

Step 3 – Name the moral injury precisely

Silently, in one sentence:

- “I feel like I just harmed this patient by following a policy I disagreed with.”

- “I feel complicit in prolonging suffering for non‑medical reasons.”

- “I feel I betrayed my values by staying silent.”

Do not sanitize it. Be brutally honest. That clarity is the entry point.

Step 4 – Rapid body scan: 3 minutes

Close your eyes if it is safe. If not, soften your gaze.

Scan:

- Face and jaw.

- Throat.

- Chest and gut.

- Hands.

Where is the distress sitting?

Lock onto the strongest sensation and stay with it:

- Notice its size, shape, and intensity.

- On each exhale, imagine giving it just 2% more space, like loosening a belt one notch.

- No mantra. No “relax.” Just: “This is what X feels like in the body.”

Example: You feel crushing weight in the chest.

“Weight in chest. Feels like a brick. Burning around it. I do not need it to go away right now. I can breathe with it for 3 minutes.”

What you are doing here: preventing the system from locking that state in as frozen armor. Letting it be felt is what allows it to move later.

Step 5 – Separate facts from the self‑story (2–3 minutes)

This is where moral distress becomes toxic or tolerable.

Write it quickly on your phone (notes app) or mentally if you must.

Facts:

- What exactly happened? (One or two sentences. No adjectives.)

- What did you do and not do?

Story:

- What are you making it mean about you as a person?

Example:

- Facts:

- “Family wanted everything done. Patient had metastatic cancer with no realistic chance of recovery. Attending insisted on continuing full code. I followed orders. I did not challenge aggressively. Patient coded and we did CPR for 40 minutes.”

- Story:

- “I am a coward who let a man be tortured because I prioritized conflict avoidance over his dignity.”

Now apply mindfulness to the story:

- Note: “Story. Harsh self‑judgment. Shame.”

- Ask one question: Is there any other possible story that also fits these facts?

You are not forcing a positive spin. You are allowing complexity.

Alternative stories:

- “I was a trainee in a hierarchy with limited power. I had moral clarity but not institutional authority.”

- “I did not like my actions and I can use that discomfort to guide how I speak up next time.”

You do not have to choose one right then. You just have to see that your initial, self‑condemning narrative is not the only option. That alone breaks the absolute grip of moral distress.

Step 6 – Choose one “next wise action”

Moral distress becomes corrosive when it stops you from acting in line with your values in the future.

Ask: Given what happened, what is one small action I can take that is more aligned with my values?

Examples:

- “I will debrief this with my attending and state clearly that I believed we were causing non‑beneficial suffering.”

- “I will bring this case to our ethics committee.”

- “I will document my concerns clearly in the note.”

- “I will talk with a trusted colleague about how to speak up earlier next time.”

- “I will block 30 minutes after my shift tonight to process this with my mindfulness practice instead of numbing with Netflix or alcohol.”

Pick one. Commit. Then return to work.

This is not about fixing the case. It is re‑establishing yourself as a moral agent, not a passive cog.

4. Using Mindfulness to Work with Specific Emotions: Guilt, Anger, Shame

Different ethical cases leave different residues. If you try to use one generic breathing exercise for everything, you will get mediocre results.

Here is a more targeted approach.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Guilt | 80 |

| Anger | 70 |

| Shame | 60 |

| Numbness | 50 |

The numbers here are not precise, but they reflect how frequently I see each emotion in moral distress cases.

Guilt: “I did something wrong”

Functional guilt can be useful. It points toward repair. Toxic guilt says, “I am irredeemable.”

Mindfulness protocol for guilt (8–10 minutes)

- Sit, breathe for 1–2 minutes.

- Bring the event to mind. Let the guilt rise.

- Locate it in the body (often chest, gut).

- Stay with that physical sensation; drop the thought story. Each time the mind jumps to “I am terrible,” label it: “thinking” and return to the sensation.

- After a few minutes, ask:

- “What, concretely, can I repair?”

- “What, concretely, can I change so this is less likely to repeat?”

Write down one action. If there is nothing you can repair (patient has died, case is closed), name this out loud to yourself. “There is no further action available. The guilt is an echo, not a current signal.”

Anger: “This should not have happened”

Anger in moral distress is often toward:

- The system.

- Specific colleagues.

- Families.

- Yourself.

Trying to “calm down” immediately is a mistake. The first step is to feel it without enacting it.

Mindfulness protocol for anger (10 minutes)

Breathe normally. Do not try to lengthen your exhale too soon; that can feel invalidating.

Bring up the triggering image or phrase.

Notice:

- Heat in the face.

- Tension in jaw, hands, shoulders.

- Racing thoughts.

Internal script: “This is anger. It makes sense that anger is here.” No judgment.

Let the sensations crest like a wave and then recede. Imagine you are watching weather move across the sky of your body.

Only after the wave starts to subside, ask:

- “What value of mine is this anger protecting?” (e.g., justice, dignity, honesty)

- “What is one constructive channel for this value? (feedback, policy change, ethics consult, documentation)”

If you skip the embodied part and go straight to “what should I do,” you will act from reactivity, not alignment.

Shame: “I am fundamentally bad”

Shame is the most corrosive and the most common in trainees. It shows up as:

- “I am not the kind of doctor I thought I was.”

- “If people knew how I handled that, they would think I am a fraud.”

Mindfulness protocol for shame (10–12 minutes)

Start with grounding breath: 4‑4‑6 pattern for 1–2 minutes.

Bring to mind the worst image or moment of the case.

Notice where you feel the urge to hide or collapse (often chest caving, eyes wanting to look down, shoulders curling).

While staying with those sensations, place a hand on your chest or abdomen. This is not woo; it gives your nervous system a second cue of safety.

Internally, say something like:

- “This is shame. It thinks it is protecting me by making me disappear.”

- “I can feel this without obeying it.”

Then ask:

- “If a colleague I respect had been in my exact situation and done exactly what I did, would I condemn them as harshly as I am condemning myself?”

- Watch the answer. Do not force kindness. Just see the discrepancy.

This is the seed of self‑compassion, which is not a luxury. It is mandatory equipment if you want to stay in medicine without hollowing out.

5. Integrate Mindfulness into Team and Institutional Practice

You will not fix moral distress as a solo hero while your institution keeps grinding people up. However, you can push the culture a few degrees in the right direction.

Quick team debrief structure that includes mindfulness

After a difficult ethical case (withdrawal of care, code on a young patient, high‑stakes missed diagnosis), run a 10–15 minute huddle if you have any authority at all. If you are a resident, you can still propose it.

Basic script:

Facts first (2–3 minutes)

One person briefly recaps the case without emotional language.Impact check (4–5 minutes)

Each person gets one sentence on how it landed:- “I am angry.”

- “I feel sick about this.”

- “I am confused.”

No fixing. No discussion yet.

60‑second guided mindfulness (1 minute)

You or someone else leads:“Everyone just close your eyes or soften your gaze. Feel your feet on the floor. Notice your breath. Notice where in your body this case is landing. No need to change it. Just notice. Three slow breaths together.”

Values and system question (5 minutes)

Two prompts:- “Where did this case align with or violate our values as clinicians?”

- “Is there anything in the system we want to flag or change?”

You are not running group therapy. You are doing two things:

- Signaling that emotional and moral impact is not a private defect, it is shared terrain.

- Teaching micro‑mindfulness as a standard part of serious clinical work.

Document and escalate patterns

Use your own distress as data.

If you regularly use the post‑case protocol and keep running into the same painful stories (e.g., “we are overtreating elderly patients with no meaningful chance of recovery because of family demands”), that is a flag for an institutional ethics issue, not just a personal resilience gap.

- Track cases in a simple spreadsheet.

- Note: date, service, nature of moral conflict, outcome, whether ethics was consulted.

| Field | Example Entry |

|---|---|

| Date | 2026-01-05 |

| Service | MICU |

| Trigger | Non-beneficial life-prolonging treatment |

| Main Emotion | Anger |

| Action Taken | Ethics consult requested |

| Follow-up Needed | Present at M&M |

Once you see patterns, you can argue for:

- More accessible ethics consults.

- Policy reviews (e.g., non‑beneficial treatment guidelines).

- Staff training on goals‑of‑care communication.

Mindfulness does not replace system change. It gives you enough clarity and stability to push for system change without burning out or exploding.

6. A Weekly “Moral Debrief” Practice You Do Alone

If you only process moral distress acutely, it will accumulate. You need a weekly clean‑out.

Schedule 20–30 minutes once a week. Sunday evening, post‑call day, whenever your brain is at least half‑functional.

Structure (20–30 minutes)

1. List the ethical friction points of the week (5 minutes)

On paper (not just mentally), jot down:

- Any case where you thought: “This feels wrong” or “I do not like what we are doing here.”

- Even if the outcome was technically “fine.”

Do not write essays. Just 1–2 sentence bullets.

2. Choose the one that still has charge (1 minute)

The one that, when you think of it, your body reacts.

3. Mindfulness + narrative review (15–20 minutes)

For that single case:

- 3 minutes of breathing and body scan.

- 5 minutes of fact vs story:

- Facts on left side of page.

- Story on right.

- 5–10 minutes of embodied processing:

- Eyes closed.

- Feel the strongest sensations linked to that story.

- With each exhale:

- “Let me feel 5% more of this.”

- “It is safe to feel this now; the event is over.”

Do not rush to “lessons learned.” You are not doing M&M. You are doing nervous system clearance.

Over several weeks, you will notice:

- Faster recovery after hard cases.

- Less rumination at 2 a.m.

- Clearer sense of where your true ethical lines are.

7. Common Mistakes That Make Mindfulness Useless (or Worse)

Let me be blunt about where people screw this up.

Mistake 1 – Using mindfulness to numb instead of feel

If your practice is basically, “Relax, empty your mind, forget about the case,” you are doing anesthesia, not mindfulness. The distress will come back louder.

Fix: Always include a period where you deliberately bring the case to mind and let the associated sensations be felt.

Mistake 2 – Treating mindfulness as a personal band‑aid for system abuse

You are not the problem if:

- Your ICU is regularly running at 150% capacity.

- You have to discharge uninsured patients to the street.

- You are pressured to meet RVU targets that conflict with good care.

Mindfulness is not there so you can endure the intolerable indefinitely.

Fix:

- Use mindfulness to see clearly where the moral injury originates.

- Use that clarity to decide:

- What you will push to change.

- What you will refuse to normalize.

- When you will leave a toxic environment.

Mistake 3 – Blaming yourself for feeling distressed

You would be more worried about a physician who feels nothing after a grotesquely misaligned case.

Fix: Reframe moral distress as evidence of intact moral circuitry. The goal is not to eliminate it. The goal is to process it so it guides you instead of poisoning you.

Mistake 4 – Doing it only when you are already in crisis

If your first attempt at mindfulness is after a catastrophic death or a patient suicide, you are asking too much of a new skill.

Fix: Start small, daily, now. Low‑stakes practice so that high‑stakes moments do not overwhelm your capacity.

8. How This Actually Feels After a Few Months

Let me set expectations. This is not magic. But it is noticeable.

If you commit to:

- 10–15 minutes most days.

- The 5–10 minute post‑case protocol after truly difficult cases.

- A weekly 20–30 minute moral debrief.

In 6–8 weeks, most people report:

- Fewer intrusive replays of cases in the middle of the night.

- Less “I am a bad doctor” and more “I was in a bad situation, and here is what I will do differently.”

- A clearer line between what they can own and what belongs to the system, their attendings, or the family.

- More ability to sit with families in ethically complex conversations without shutting down or overcontrolling.

You will still have days that wreck you. This work does not make you immune. It gives you a way to metabolize the injury instead of just stacking it in the back of your mind until it collapses on you.

9. A Simple 2‑Week Starter Plan

If you want something concrete to start tomorrow, use this:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Day 1-3 | 10 |

| Day 4-7 | 15 |

| Day 8-10 | 20 |

| Day 11-14 | 25 |

Think of the values as total minutes per day (average).

Days 1–3

- 10 minutes daily:

- 5 minutes breathing with counting.

- 5 minutes body scan.

- Use the 3‑breath grounding whenever you feel a strong reaction.

Days 4–7

- 12–15 minutes daily:

- Same structure, add 1–2 minutes of emotion labeling at the end.

- Do the full 5‑minute post‑case protocol once, for any case that sticks with you.

Days 8–10

- 15–18 minutes daily.

- One 20‑minute weekly moral debrief.

Days 11–14

- Keep the same.

- Try leading a 60‑second mindful pause in one team huddle after a tough event.

After two weeks, reassess:

- Is it helping at least a little?

- What obstacles are real vs excuses?

Adjust, but do not drop it to zero. This is not a fad practice. It is how you protect your core values while working inside a system that will, inevitably, conflict with them.

Key Takeaways

- Moral distress is not generic burnout; it is the injury of acting against your values. Treat it with tools tailored to that, not generic “stress relief.”

- Mindfulness, done correctly, is not about numbing. It is about feeling the moral pain in your body, seeing the story clearly, and then choosing a more aligned action.

- A realistic protocol—daily baseline, short post‑case practice, weekly debrief—can keep moral distress from hardening into cynicism or collapse, and can actually sharpen your ethical voice instead of silencing it.