The fastest way to kill your leverage in a new job is to ask for more money in week one.

You get one clean launch in a new role. Especially in medicine, where reputations spread faster than policy memos. The first 90 days are not just a probation period; they are your evidence file for every future conversation about pay, schedule, and benefits.

You want more control over your life and your income. Good. You should. But timing is everything.

Here is how to run those first 90 days, week by week, so that when you finally say, “We should revisit my compensation and schedule,” you are impossible to ignore—not easy to dismiss.

Overview: The 90‑Day Strategy

Before we drill down week by week, understand the phases:

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Phase 1 - Days 1-30 | Observe and document |

| Phase 2 - Days 31-60 | Prove value and test boundaries |

| Phase 3 - Days 61-90 | Position and negotiate |

- Days 1–30: Shut up and watch. Learn the system, people, and unspoken rules. Capture data.

- Days 31–60: Show you are above baseline. Quietly outperform. Start small schedule micro‑asks.

- Days 61–90: Ask deliberately. Bring evidence, market data, and specific proposals for pay/schedule.

If you start campaigning for a four‑day week on day 7, you look entitled. If you wait until month 18, you have likely anchored yourself too low.

Days 1–30: Observation and Intel, Not Demands

At this point you should be gathering ammunition, not firing shots.

Week 1 (Days 1–7): Learn the Game Before You Change It

Your only “agenda” in week 1:

- Figure out how things actually work (not what HR told you).

- Become obviously reliable and low‑maintenance.

- Start a private record of workload and expectations.

Do this in week 1:

Clarify the written deal you already signed

- Base salary, RVU or shift expectations

- Call responsibilities

- Overtime rules / moonlighting permissions

- Benefits start dates (health, 401k, CME, loan repayment)

Map the unwritten deal Ask senior colleagues informally:

- “What does a normal week look like for you here?”

- “Who approves schedule swaps?”

- “Who actually decides bonuses?” (often not HR)

Start a simple “leverage log” (one document, not shared with anyone):

- Shifts worked, hours, patient load

- Extra tasks: committees, teaching, covering call, precepting

- Problems you fixed or prevented

- Any praise (“That discharge summary saved us,” “Clinic flow runs smoother when you are here”)

At this point you should not:

- Ask for a raise

- Ask to cut your shifts

- Ask for a permanent schedule change

- Send long emails about how “at my last job we did it this way”

You are still under the microscope. Pass that test first.

Week 2 (Days 8–14): Understand Schedules and Power

Now that you know the doors, figure out who holds the keys.

Focus on:

Schedule mechanics

- Who builds the master schedule?

- How far in advance is it done?

- How are call weeks assigned?

- What is the actual process for swaps?

Real decision‑makers Pay and schedule changes are rarely decided by:

- The friendly office manager

- Your favorite colleague They are usually decided by:

- Section chief or medical director

- Practice manager / service line admin

- Sometimes a comp committee

Culture test Watch how others talk about:

- Extra shifts: “We all pitch in” vs “Do not ever say yes”

- Overtime: “We just eat it” vs “We bill every minute”

- Schedule protection: “Fridays are sacred” vs “Everything’s negotiable”

At this point you should start to see where your future levers are. But you still are not pulling them.

Weeks 3–4 (Days 15–30): Define Your Value and Market Position

By now you are less “new” and more “known quantity.” Time to understand your market strength.

Tighten your performance

- Be on time. For everything.

- Finish notes by end of day when possible.

- Answer messages before you leave. This sounds basic. Most new hires fail here. You will not.

Benchmark your role against the market

Get real numbers, not rumors:

| Item | Where to Find It |

|---|---|

| Regional salary range | MGMA, Doximity, colleagues |

| Typical RVUs per FTE | MGMA, specialty societies |

| Standard call frequency | Peers at other institutions |

| Common FTE structures | Job boards, recruiter emails |

- Confirm your moonlighting and side‑work boundaries

- Is outside clinical work allowed? Under what conditions?

- Are you allowed to consult, teach, or telehealth on the side?

- Any non‑compete or “no moonlighting” buried in onboarding packets?

At this point you should know:

- Whether you are under‑, fairly, or over‑paid for your region

- How painful your call schedule is compared with peers

- Whether you have realistic leverage (shortage specialty, high productivity, leadership need)

You should still not be asking for more money or fewer shifts. You are building the case.

Days 31–60: Prove Value and Test Small Boundaries

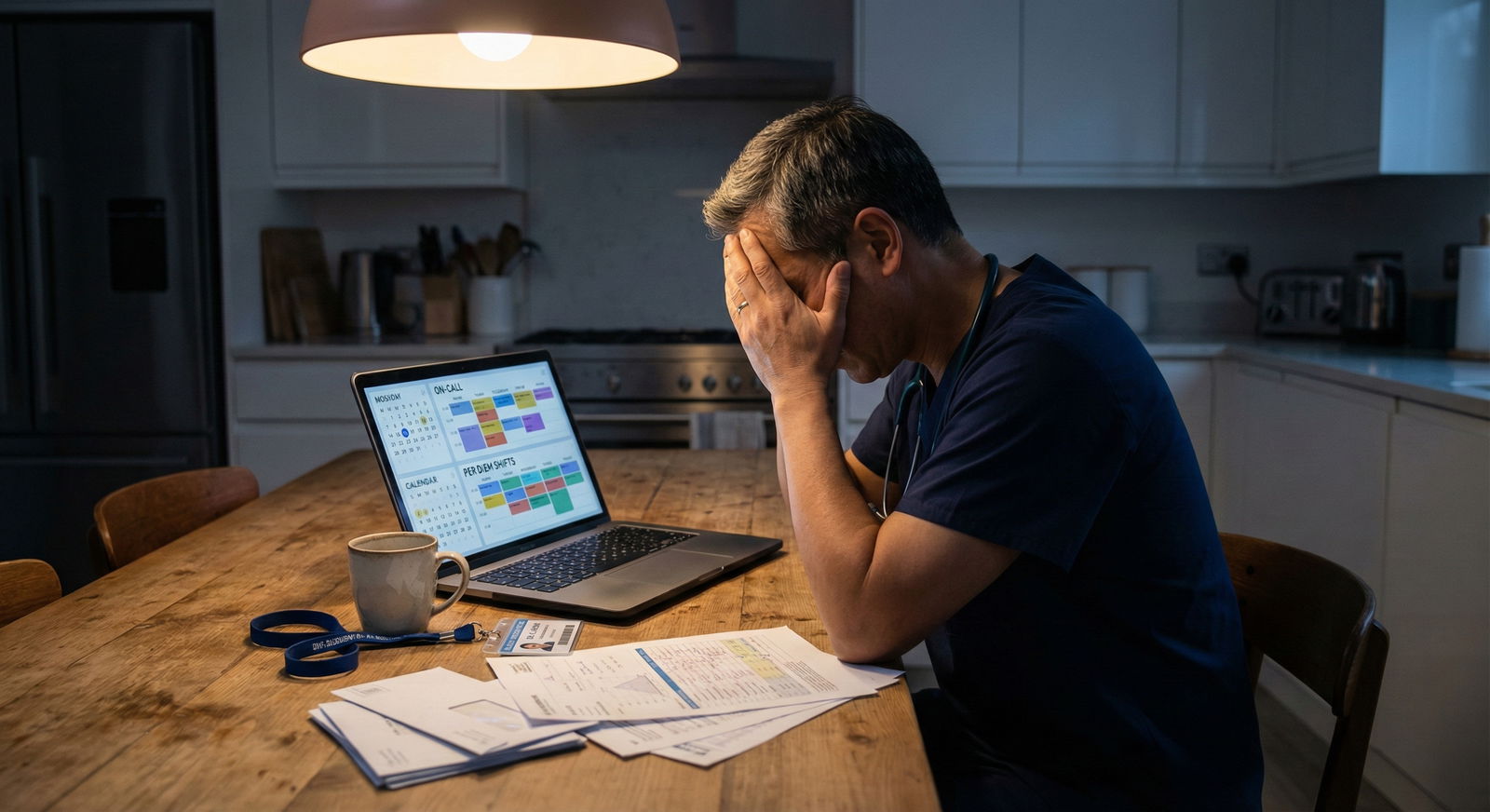

This is where most people either set themselves up as “indispensable” or get filed mentally as “just another hire.”

Weeks 5–6 (Days 31–45): Show You Are Above Baseline

At this point you should be clearly exceeding minimum expectations.

Concrete targets:

Reliability

- Zero avoidable no‑shows to clinic or OR.

- Minimal schedule chaos. If you need a change, you solve it, not your manager.

Team impact Pick one or two small but visible contributions:

- Streamline a handoff template.

- Volunteer to cover an isolated hard‑to‑fill shift (once, not habitually).

- Offer to precept residents one afternoon.

Ideally, your name starts getting attached to phrases like:

- “Clinic ran smoother today.”

- “He picks up the tough patients without complaining.”

- “She is easy to schedule with.”

Those are negotiation chips later.

This is also the time to quietly test micro‑flexibility:

- Ask for a one‑off schedule tweak:

- “Could we switch my Tuesday afternoon clinic to Wednesday this week so I can attend [legitimate event]?”

- “If I pick up that Sunday call, is it possible to protect my post‑call Monday morning?”

You are not asking for a permanent change. You are testing:

- Are they rigid or reasonable?

- Who approves what?

- Does anyone complain when you make a reasonable request?

Weeks 7–8 (Days 46–60): Shape Your Narrative and Identify Your Angles

Now you begin positioning yourself for the real ask coming in days 61–90.

Compile a simple 1‑page “impact snapshot” for yourself Not to share yet. For you.

Include:

- Average weekly patient volume vs expectations

- Any metric improvements (no‑show rate, throughput, length of stay)

- Positive feedback from staff, patients, colleagues

- Extra duties you have quietly taken on

Identify which lever you actually want to pull first

Pick one primary goal for the upcoming conversation:

- Higher base salary?

- Different schedule (fewer nights/weekends, 4‑day week)?

- Formal moonlighting permission / protected time?

- Productivity bonus structure?

Trying to “fix everything” at once is how people get stonewalled.

- Reality check: Do you truly have leverage?

You have leverage if several of these are true:

- Shortage specialty (EM, anesthesia, psych, hospitalist in many regions)

- You are already performing at or above the median RVUs or workload

- They are short‑staffed and scrambling to cover

- Recruitment is ongoing and slow

You have limited leverage if:

- Oversupplied or ultra‑desirable location

- Multiple people can do your exact job tomorrow

- You are still struggling with basics (charting backlog, complaints, lateness)

At this point you should have a clear picture:

- What you want to change

- Why they should care

- How desperate they are to keep you happy

You are almost ready to ask.

Days 61–90: Time to Negotiate, Not Just “Check In”

This is where adults either negotiate, or they stay resentful and stuck. Your call.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Days 1-30 | 70 |

| Days 31-60 | 40 |

| Days 61-90 | 20 |

(Interpretation: earlier days are heavier on observation; later days on negotiation. The numbers here are “percent effort” on observation vs negotiation, not hours.)

Weeks 9–10 (Days 61–75): Set Up the Conversation Properly

At this point you should request a formal meeting, not ambush your supervisor in the hallway.

How to set it up:

- Email your direct supervisor or medical director:

- “I would like to schedule time in the next couple of weeks for a 30‑minute check‑in to review how things are going and to discuss alignment of my role, schedule, and future here.”

- Do not mention “raise” in writing yet. That spooks admin‑minded people.

Prepare for that meeting like it is an interview:

Print your 1‑page impact snapshot

- Start with facts: volume, call coverage, extra roles.

- Keep it clean, no whining, no drama.

Update your market data

- Regional salary range for your specialty and FTE level.

- Typical call frequency in similar settings.

- Any changes in local hiring (e.g., three open positions posted for your role).

Have a specific proposal Examples:

- Pay‑focused: “Move base from $X to $Y, aligning closer to the regional median for my workload.”

- Schedule‑focused: “Formalize a 0.8 FTE schedule with four 10‑hour days, with proportional pay adjustment.”

- Hybrid: “Maintain current base, but add a clear productivity bonus above [RVU threshold] and reduce mandatory weekends from 2 per month to 1.”

You are not going in to “see what they offer.” You are going in with an anchor.

Weeks 11–12 (Days 76–90): Make the Ask and Manage the Response

When you actually sit in the room, do not wander. Run a structured conversation:

Open with contribution, not complaint

- “I am glad to be here. Over the past two and a half months I have been seeing X patients per week, covering Y call, and have taken on Z additional responsibilities.”

- Show them you know your own numbers.

Then pivot: fit and sustainability

- “I want this to be sustainable long term. To do that, I would like to revisit how my compensation and schedule align with both the market and the work I am doing.”

State your proposal clearly

- “Given the current benchmarks and my contributions, I am asking to move my base salary from $260,000 to $290,000 starting with the next contract year.”

- Or: “I am asking to shift to a four‑day schedule with no reduction in total RVU expectations, with call remaining as is.”

No long story. No 15‑minute narrative about burnout in medicine. They have heard it all already.

- Shut up and let them respond

You will typically hear one of three things:

“Let me look into this.”

- Good. You are still in play. Ask: “What is the usual process and timeline for decisions like this?”

“We cannot change base pay mid‑year.”

- Fine. So you pivot to:

- “What about a structured productivity bonus starting now?”

- “Can we adjust my schedule or call instead to match the current compensation?”

- Fine. So you pivot to:

“We do not negotiate individually.”

- Translation: “We do not negotiate easily.” Not “never.”

- Follow‑up: “Then how are exceptions made when someone’s role or workload changes significantly?”

At this point you should:

- Get a clear next step:

- “I will review this with administration next week and get back to you by [date].”

- Consider trading:

- Slightly less money increase now for better schedule.

- Formal moonlighting permission in lieu of big raise.

Where Moonlighting and Benefits Fit Into This

You are in the “Moonlighting and Benefits” world, so you care about more than just base pay.

Here is how to time those asks in the first 90 days.

Moonlighting

At this point you should not be sneaking in extra shifts elsewhere and hoping no one notices.

Timeline:

Days 1–30:

- Read every line of your contract about outside work.

- Ask HR for the formal policy on secondary employment.

Days 31–60:

- If the policy is vague, ask for clarification, not permission:

- “Several colleagues in my specialty moonlight elsewhere. What is the formal process to be approved for that here?”

- Map out your realistic availability without compromising performance in your main job.

- If the policy is vague, ask for clarification, not permission:

Days 61–90:

- In your “alignment” meeting, add:

- “I am interested in picking up limited external shifts, primarily nights/weekends, to accelerate my loan repayments. As long as it does not conflict with my primary schedule or productivity targets, is there a formal approval pathway for that?”

- If they say no:

- Ask if internal moonlighting (extra shifts, locums within the system) is possible as a paid add‑on.

- In your “alignment” meeting, add:

Benefits and Non‑Salary Perks

You usually have less leverage here early, but they are often easier to move than raw salary.

By day 90 consider targeted asks like:

- CME:

- “Given my interest in [subspecialty/procedure], would the department support an additional $X CME stipend or days to attend [specific course] this year?”

- Retirement match:

- Harder to move, but you can sometimes negotiate earlier eligibility if you were hired mid‑cycle.

- Call pay:

- “I noticed that inpatient call is uncompensated here, while regional standards often include a stipend. Is there any flexibility to add a modest call stipend, especially as we are currently short‑staffed?”

You are not going to overhaul the entire benefits structure in month three. But you can often carve out exceptions that matter disproportionately to your wallet and sanity.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Schedule Flexibility | 35 |

| Extra CME/Perks | 25 |

| Formal Moonlighting OK | 20 |

| Base Salary Increase | 20 |

Red Lines: When to Push Harder or Plan Your Exit

Some environments do not reward reasonable negotiation. They punish it. Recognize that early.

By day 90, if you see this pattern:

- Every schedule ask is denied with no explanation.

- Compensation data and policies are “secret.”

- People who raise concerns get quietly punished with bad shifts.

- Turnover is obviously high and everyone is cynical.

Then the smart move is not to keep begging for a raise. It is to start planning your exit and use this job as a short‑term bridge.

At this point you should be honest with yourself:

- Are you underpaid and overworked with no path to change?

- Or did you simply start negotiating too early, with too little evidence?

Fix the second. Walk away from the first.

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. Is it ever OK to ask for a raise in the first 30 days?

Almost never. The only reasonable exception is when the job you walked into is materially different than what was promised—dramatically higher workload, very different schedule, or bait‑and‑switch on call. Even then, frame it as, “We need to reconcile what was agreed upon with what is happening,” not “I want more money because this is hard.” For standard roles, build your case for at least 60 days first.

2. What if my supervisor says, “We review compensation annually,” and my review is 10 months away?

Then you negotiate what you can now, and plant a flag for the annual review. For example: get written agreement that at the annual review, your base will be revisited based on current productivity, with reference to specific benchmarks. Or lock in schedule improvements now (fewer nights, more predictable shifts) and treat the pay raise as phase two.

3. How aggressive can I be about moonlighting early on?

You can be direct, but you cannot be sloppy. By 60–90 days you can absolutely say, “I would like to pick up X external shifts per month; here is how I will protect my primary responsibilities.” What you cannot do is start taking outside work before clarifying the rules, then confess after the fact. That is how people end up labeled “untrustworthy,” and that label kills your leverage faster than any dollar amount you are trying to earn.

Key points:

- Use days 1–30 to observe, gather data, and not complain; you are building your future case.

- In days 31–60, prove you are above baseline and identify exactly which lever—pay, schedule, moonlighting—you want to pull first.

- In days 61–90, schedule a formal conversation with evidence and a specific proposal, and be prepared to trade between money, time, and flexibility.