The idea that you have to be a hyper-aggressive “Type A gunner” to match into a competitive specialty is exaggerated. And honestly? It’s messing with people’s heads more than it’s helping anyone.

You’re probably here because you’re looking at fields like derm, ortho, plastics, ENT, IR, neurosurg, maybe even competitive programs in IM or EM, and your brain is running this script on repeat:

“I’m not intense enough.”

“I’m not cutthroat enough.”

“I don’t love ‘the grind’ like those people.”

“Does that mean I don’t belong?”

Let me say this clearly: you do not need to become a caricature of a Type A robot to succeed in a competitive field. But yes, some personality traits do matter. Just not in the cartoon way you’re imagining.

Let’s pull that apart before your anxiety fills in the gaps with worst-case scenarios.

The Myth of the “Perfect Competitive Specialty Personality”

You’ve met that person. The stereotype.

The always-standing, always-answering, always-emailing-at-11:59-pm student. Somehow on three papers, four leadership roles, running marathons, and still has time to pimp themselves out in front of the PD. Talks about “the grind” like it’s a personality.

And you’re thinking: “Well, that’s not me. I get tired. I like sleep. I need time alone. I don’t want to talk every second of rounds. I second-guess myself. Am I already disqualified?”

Here’s the thing I’ve seen over and over:

- The loudest people on rotations are not always the best.

- The most visibly “Type A” applicant is not always the one programs rank highest.

- The people who act like they were “born for derm/ortho/whatever” often crash hard when actual residency hits.

Programs don’t sit in the conference room saying, “We need 10 more socially dominant gunners.” They’re saying:

- “Will this person show up and do the work without being babysat?”

- “Can I stand being in a call room with them at 3 a.m.?”

- “Are they going to fall apart, disappear, or turn toxic under pressure?”

That’s it. That’s “personality fit” in real life. Not “Type A vs Type B.” More like “functional human vs walking problem.”

What Programs Actually Look For (That You’re Calling ‘Type A’)

You’re probably labeling certain traits as “Type A,” when really they’re basic professional behaviors that lots of different personalities can pull off.

Let me strip the fluff and give you the core traits competitive programs actually care about:

- Reliability

- Work ethic

- Team compatibility

- Emotional stability under stress

- Curiosity / willingness to learn

- Professionalism (including communication with nurses, staff, patients)

Notice what’s not on this list:

- “Talks the most on rounds”

- “Gives off alpha energy”

- “Has zero hobbies”

- “Smiles 24/7 and never seems tired”

- “Loves waking up at 4 a.m. and calling it ‘the grind’”

Competitive specialties are not collecting a museum of identical Type A specimens. They’re building a team that can survive brutal hours, technical demands, and high-risk decisions without imploding.

Different personalities can do that.

Introverts. Quiet people. Self-doubters. People who need time to process. People who like structure but don’t want to be the loudest in every room.

You just have to show those core traits in your own way.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Reliability | 95 |

| Team Fit | 90 |

| Work Ethic | 88 |

| Board Scores | 85 |

| Extroversion | 20 |

Personality vs. Performance: You’re Mixing Them Up

Here’s the anxious brain trap: you’re turning performance issues into personality flaws.

“I get overwhelmed sometimes → I’m not ‘built’ for this specialty.”

“I’m not naturally aggressive → I can’t advocate for myself → programs will hate me.”

“I need time to think before answering → I must look dumb.”

No. You’re blending three separate things and calling it “I’m just not Type A”:

Skills you can learn

Speaking up on rounds, presenting efficiently, asking good questions, advocating for patients, organizing your time — that’s training, not personality.Habits you can build

Following up on orders, responding to emails promptly, showing up early, reading regularly, prepping before cases — again, habits, not some fixed trait.Real temperament

How much stimulation you like, how social you are, how you recharge, your baseline anxiety level — this is the part that is actually “personality.”

You can be an anxious, quiet, internal-processor student and still be:

- Relentlessly reliable

- Obsessed with doing good work

- Calm with patients even if you’re panicking inside

- A great teammate

That’s what matters.

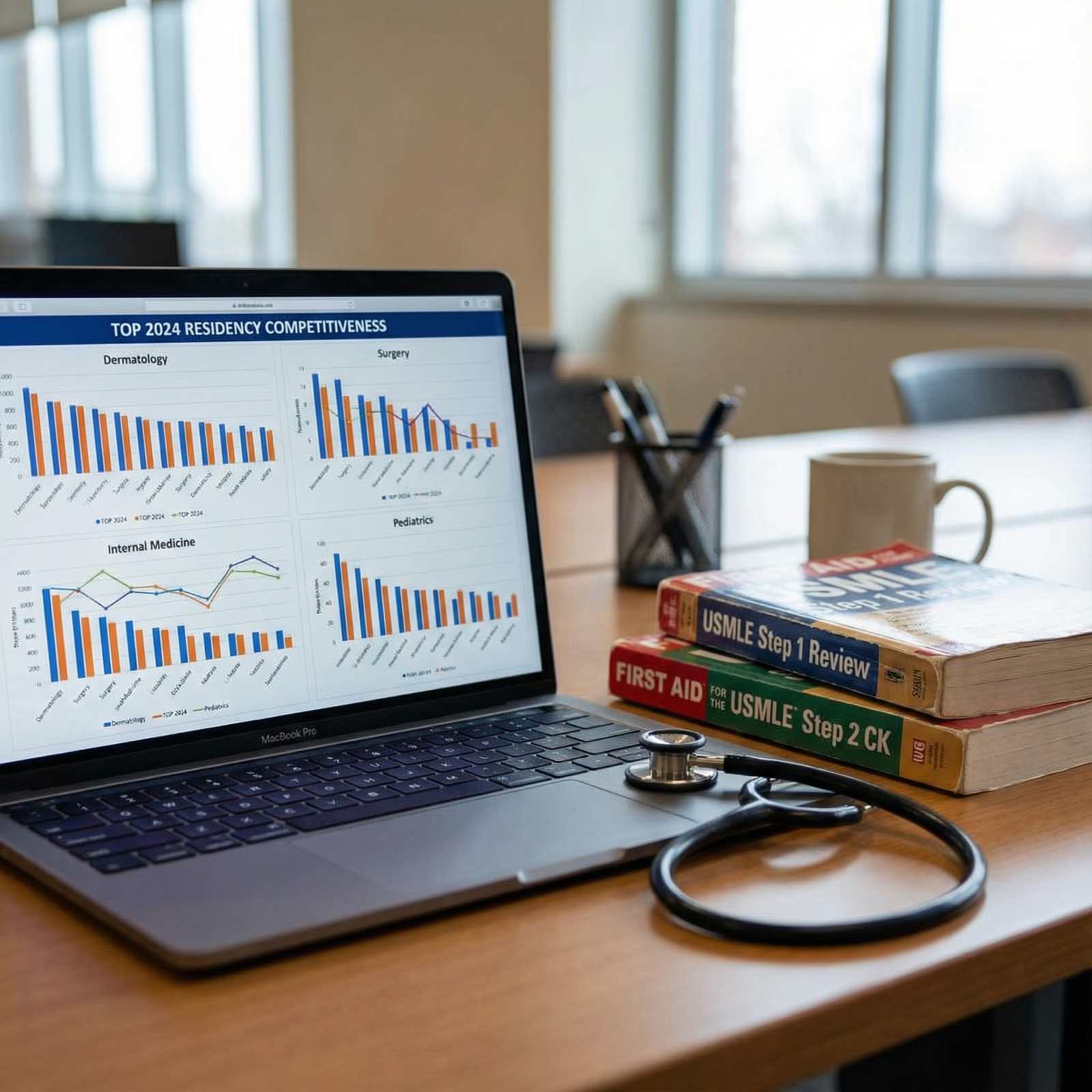

Do Certain Fields Skew Toward Certain Personalities? Yes. But That’s Not the Same as a Gate.

Let’s be honest. The stereotypes don’t come from nowhere.

- Ortho: loud, athletic, “bro” energy, loves power tools.

- Derm: polished, detail-obsessed, likes control and predictability.

- ENT/Plastics: surgically inclined, perfectionistic, image-conscious.

- EM: fast-paced, adrenaline, can tolerate chaos.

- IR: techy, procedural, likes toys and problem solving.

- Neurosurg: absurd work ethic, borderline masochistic schedule-wise.

I’ve seen versions of all of those.

But I’ve also seen:

- Quiet ortho residents who don’t say a word in the lounge but are absolute monsters in the OR (in a good way).

- Soft-spoken derm attendings who are deeply kind, slow to speak, and brilliant.

- EM docs who are calm, not high-energy at all, but somehow anchor the entire room.

- Neurosurgery residents who are surprisingly gentle, almost shy, and just quietly outwork everyone.

Fields have “vibes.” They do. But within those fields, there’s much more diversity than med student rumor mill suggests.

What you actually need is tolerance for the field’s baseline:

- In EM, can you function in constant interruptions and noise?

- In ortho, can you handle blunt, direct communication without taking everything personally?

- In derm, can you live with the precision and repetitive pattern recognition without losing your mind?

- In neurosurg, can you survive the schedule without breaking?

That’s far more important than whether you “feel” like a Type A person.

The Real Personality Red Flags (That Have Nothing To Do With Being Quiet or Anxious)

If programs pass on someone because of “personality,” it’s usually for reasons that have nothing to do with how high-energy or confident they are.

The stuff that kills applications:

- Chronic complaining on rotations

- Arguing with nurses or staff

- Being defensive when corrected

- Gossiping about co-residents or attendings

- Disappearing when there’s work to do

- Blaming others constantly

- Not reading or improving despite feedback

You can be introverted, anxious, reserved, even awkward — and still be a fantastic, recruitable candidate — if you:

- Own your mistakes

- Are kind to everyone (especially when tired)

- Consistently follow through

- Don’t suck energy out of the team

Your anxiety is telling you they want “aggressive leaders”; they actually want “emotionally safe, dependable coworkers.”

No PD is saying, “We almost ranked her, but she was too calm and quiet.” I’ve seen them say, “He’s brilliant, but I don’t want to be stuck on call with that attitude.”

Big difference.

Where Personality Does Bite You (And What You Can Actually Work On)

There are a few specific areas where your natural tendencies might make things harder — not impossible, but harder — in competitive specialties.

1. Advocacy For Yourself

If you’re conflict-avoidant or terrified of seeming pushy, you might:

- Not ask for letters early enough

- Not tell attendings you’re interested in their field

- Not ask to scrub, close, or do more hands-on stuff

- Not clarify expectations on rotations

Programs can’t guess you’re interested. If you’re quiet, you just have to pick small, specific moments to speak up.

Example phrases you can literally copy-paste into your brain:

- “Dr. X, I’ve really enjoyed this rotation. I’m strongly considering [specialty] and would love any feedback on how I’m doing.”

- “If there are any cases where I could be more involved or help close, I’d really appreciate the chance to learn.”

- “I’m applying to [specialty] and was wondering if you’d feel comfortable writing me a strong letter.”

That’s not being a gunner. That’s being an adult.

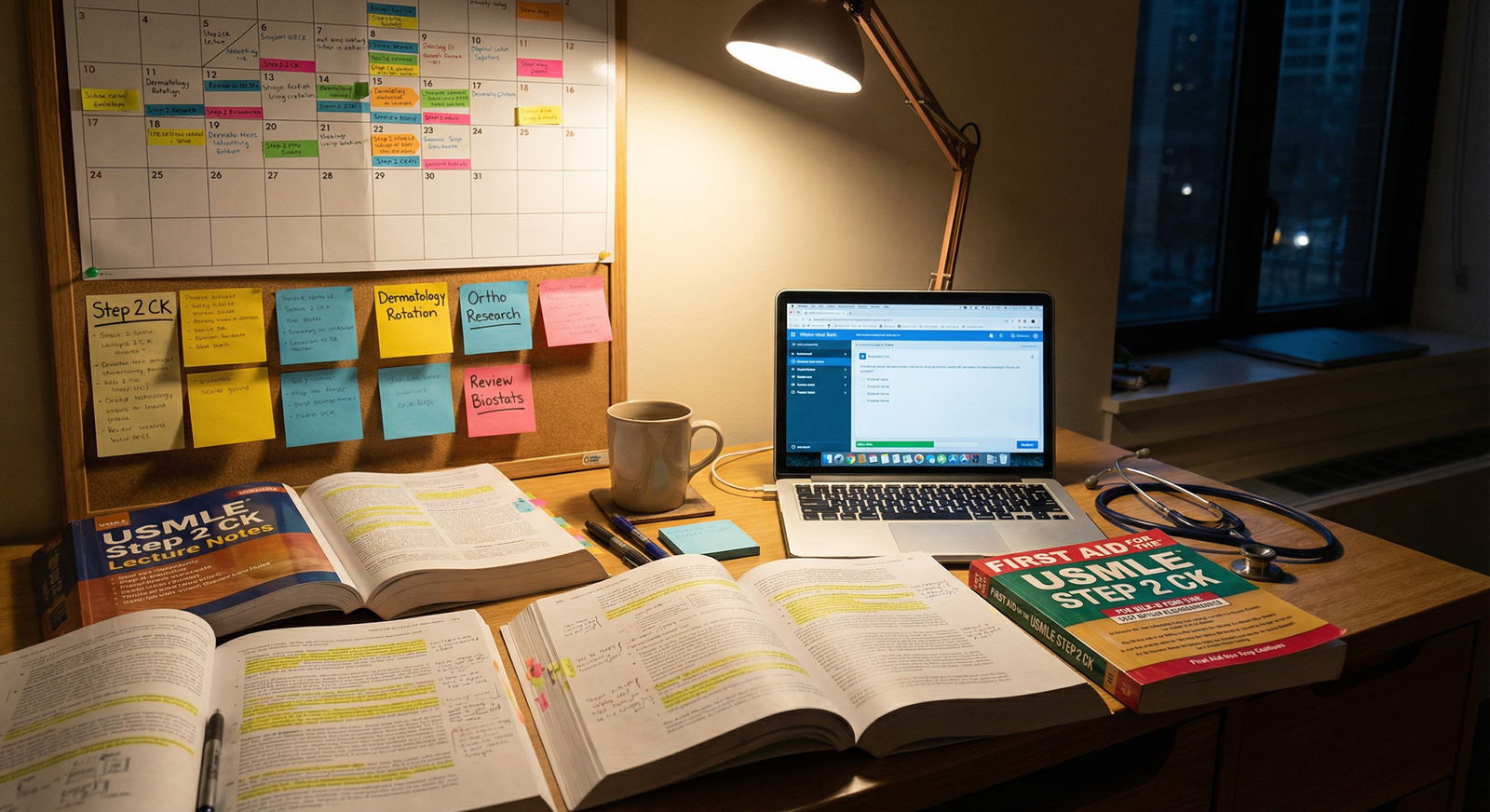

2. Tolerating Stress Without Collapsing

Some people naturally run anxious. Hi. Us.

Competitive fields often amplify that: high stakes, long hours, more eyes on you.

You don’t need to magically become chill. You do need systems so your anxiety doesn’t run the show.

What I’ve seen help:

- Predictable routines: same pre-rounding structure every day, same way of prepping cases

- Externalizing tasks: checklists, notes, reminders instead of trying to remember everything

- Micro-breaks: 60 seconds in the bathroom just to breathe, reset, and not spiral

- Pre-committed coping: you already know who you’re texting/calling after a bad day instead of stewing alone

Programs care less that you feel stressed and more that you still function and treat people decently while stressed.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Your Baseline Personality |

| Step 2 | Habits and Skills |

| Step 3 | Clinical Performance |

| Step 4 | Letters and Reputation |

| Step 5 | Interview Invites |

| Step 6 | Residency Match |

| Step 7 | Stress Response |

3. Communicating on Rounds and in the OR

If you’re not naturally talkative, teaching-heavy, high-pressure environments can feel like performance stages. It’s awful.

But here’s the trick: programs are not grading you on charm; they’re grading you on clarity and engagement.

You don’t have to be entertaining. You do have to be:

- Audible

- Organized in your presentations

- Willing to answer questions (even if you’re wrong)

- Occasionally willing to ask, “Can you walk me through why we did X instead of Y?”

You can be quiet 90% of the time, and then say one thoughtful thing that shows you’re thinking and cared enough to read. That lands way better than constant noise.

| Factor | Personality-Dependent? | Behavior You Can Control |

|---|---|---|

| Being loud/extroverted | Mostly | Not required |

| Reliability on service | No | Completely controllable |

| How you process stress | Partly | Coping skills help a lot |

| Speaking up for opportunities | Partly | Script and practice |

| Getting strong letters | No | Show up and do good work |

The Silent Fear: “What If I Force Myself In and Then Hate It?”

Ah yes, the other voice:

“Even if I somehow fake being Type A enough to match ortho/derm/whatever… what if I just crumble? What if everyone else thrives on this and I burn out in PGY-2 and everyone says, ‘Yeah, we knew they weren’t really like us.’”

This is the disaster fantasy.

Here’s reality:

Most people in competitive fields are not actually loving every second. They’re tolerating a lot of misery to get to the parts they love. You’re not uniquely fragile for feeling that.

Burnout is not a personality failure. Extroverts burn out. Gunners burn out. People who “always wanted to be a surgeon since age 5” burn out.

You can do genuine testing instead of guessing based on vibes:

- Take electives in that field.

- Watch the residents at 4 p.m., not just at 7 a.m.

- Ask them, “What parts of your personality help you here? What parts make it harder?”

If being around them feels draining all the time, if the field values behaviors you absolutely cannot stand behind (not just “tough” but ethically or personally wrong for you), then maybe it’s not a fit. But that’s not because you’re not “Type A.” That’s because you’re not willing to trade your whole self for a job. Valid.

Worst-Case Scenarios Your Brain Is Probably Playing

Let me call out the three big horror stories and answer them directly.

Horror Story 1: “Everyone Will See I’m Not One of Them”

You imagine walking into a derm/ortho/ENT pre-interview dinner and instantly standing out as the quiet, awkward one among a table of confident extroverts.

Reality: every dinner has several flavors of awkward. And the faculty are not recruiting for a frat; they’re thinking, “Can I staff this person on my service?”

If you’re polite, engaged, ask a few questions, don’t dominate, don’t say anything bizarre or cruel — you’re fine. Being quieter is not a red flag.

Horror Story 2: “My Anxiety = I Can’t Handle a High-Stress Field”

Anxiety feels like weakness. But anxious people are often hyper-prepared, detail-oriented, and empathetic — which can be major assets in patient care.

What destroys people isn’t anxiety alone; it’s untreated, denied, or unmanaged anxiety, mixed with zero support and toxic culture.

If high-risk procedures or codes make you feel alert-but-capable, that’s not a disqualifier. If they make you completely freeze and dissociate, then you might want to really think about procedural-heavy, crisis-heavy fields.

But you won’t know which it is just from your self-label as “not Type A.” You have to expose yourself to the real environment and see what your body does.

Horror Story 3: “If I Can’t Be the Alpha, I Won’t Stand Out”

You’re imagining programs only remembering the loudest, boldest students.

Residency selections are far more often based on:

- Consistent solid performance on rotations

- Strong, specific letters: “They showed up early, stayed late, did whatever was needed, and patients loved them.”

- Board scores and transcript

- Interview behavior that signals “safe teammate,” not “center of attention.”

Being the loudest student can backfire if there isn’t real substance behind it. The resident who quietly closed the incision perfectly, followed up labs, and didn’t make drama is the one attendings fight over.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Rotation performance | 95 |

| Letters of recommendation | 90 |

| Interview impression | 85 |

| Board scores | 80 |

| Extroversion/Charisma | 25 |

One Hard Truth: You Can’t Outsource This Decision to Vibes

Here’s the part your anxious brain is hoping to avoid: you don’t get to stop at “I’m not Type A, so I guess I can’t do it.”

You have to actually test reality:

- Rotate in the field (preferably at a home or nearby academic program).

- Ask residents bluntly about their personalities and struggles.

- Notice how you feel at 3 p.m. and 3 a.m., not just on day 1.

- Track your own behavior: Are you still kind? Still functioning? Or completely unraveling?

If after honest exposure you still want it — not the status, but the work — then your lack of stereotypical Type A-ness is not the barrier your brain thinks it is.

What You Can Do Today If You’re Spiraling About This

Don’t sit in your head looping “I’m not Type A enough” for the next six months. That’s how people self-eliminate from fields they actually might love.

Do something specific. Today.

Here’s your next step:

Right now, open a note on your phone or laptop and make two short lists:

- “Traits I’m worried I don’t have” (e.g., super extroverted, confrontational, loves chaos)

- “Behaviors I can show consistently” (e.g., I follow through, I prepare, I’m kind to patients, I’m good under pressure even if I feel anxious)

Then pick one behavior from list #2 that already matches what competitive programs value — reliability, work ethic, team player, curiosity — and plan one concrete action this week that shows it on your current rotation.

Email a resident to ask for feedback. Read before a case and ask one thoughtful question. Volunteer to follow up on a task and actually close the loop.

Do that instead of letting the “Type A” stereotype convince you you’re disqualified before you even step on the field.