The blanket belief that “old academic programs train better doctors than new community programs” is lazy, outdated, and wrong in a lot of cases.

I’ve watched residents at shiny “top-10” university hospitals barely touch a basic bread‑and‑butter case… while a PGY‑2 at a supposedly “no‑name” community program managed that same condition independently on night float. The halo effect around big-name academic centers is powerful. It’s also blinding.

Let’s dismantle the myths with what actually matters: data, structure, and what you’ll be doing at 2 a.m. when nobody is holding your hand.

Myth #1: Age and Academic Branding = Training Quality

The default narrative goes like this:

Old program → more prestige → better faculty → better training → better outcomes.

New community program → weaker → riskier → worse jobs.

That chain falls apart as soon as you look closer.

What the actual data shows

Program “age” is not one of the ACGME’s core quality metrics. At all. When surveyors evaluate programs, they’re looking at:

- Case logs and procedure numbers

- Clinical exposure and patient volume

- Faculty qualifications and supervision

- Didactic structure and evaluation systems

- Board pass rates and resident performance

I’ve seen brand-new community programs posting 100% board pass rates in their first graduated classes while some legacy academic programs sit in the low 80s. You will not see that on a glossy website, but it’s sitting in ACGME and board data.

Here’s the dirty secret: some old academic programs are coasting on reputation they earned in the 1980s. The faculty who built that reputation are retired. The case mix has shifted. The resources moved to a different campus. But the website still says “founded in 1952” like that magically guarantees your learning in 2026.

New community programs, on the other hand, usually get hammered with heightened ACGME scrutiny for the first several years. They over-document. They over-prepare. They bend over backwards to show their graduates are competent and board-ready. That pressure often forces them to build very intentional curricula instead of relying on tradition and inertia.

Is every new community program excellent? No. Some are rushed, under-resourced, and should be avoided. But “new” and “community” are not synonyms for “bad.”

Myth #2: Community = Weak Pathology and Limited Exposure

The favorite line from some academic hardliners: “You won’t see enough complex pathology in a community program.”

Sometimes true. Often false. And deeply context dependent.

Here’s what actually happens in many regions:

Tertiary academic centers: pull in ultra‑rare cases, lots of referrals, transplants, quaternary care. Great for esoteric zebras and research. But they also carve out entire service lines where residents barely touch the patients (think highly specialized ICUs or procedural suites dominated by fellows).

Strong community or “hybrid” programs: soak up insane volumes of bread‑and‑butter pathology—DKA, COPD exacerbations, NSTEMIs, sepsis, trauma, common surgeries—over and over again, with high autonomy. Less zebra density, more repetition of what you’ll actually practice.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Tertiary Academic | 220 |

| Hybrid Community-Academic | 260 |

| High-Volume Community | 310 |

Volume matters for skill. You do not learn to manage CHF by hearing a grand rounds talk about it. You learn by writing 40 CHF admission notes in two months, adjusting diuretics, seeing what happens when you over-diurese someone with CKD, and discussing the fallout the next morning.

In a lot of specialties—internal medicine, emergency medicine, general surgery, family medicine—high‑volume community hospitals are exactly where the bulk of real-world pathology lives. That’s why many old academic departments quietly send their med students and residents to affiliated community sites “for better exposure.”

Ask yourself: when you’re practicing independently, where are you more likely to work? A quaternary transplant center? Or something that looks suspiciously like that “no-name” community program you’re currently side‑eyeing?

Myth #3: Academic Programs Have Better Teaching and Mentorship

This one sounds plausible. More faculty, more grants, more teaching awards… must mean better education, right?

Not necessarily.

Old academic programs often have:

- Faculty who are promotion-driven and research-focused

- Thick layers of fellows between you and the interesting work

- Didactics that are brilliant on paper, mediocre in the room

- A culture where residents are “free labor for the machine”

I’ve sat in “prestigious” noon conferences where half the room was charting, the slide deck hadn’t been updated since 2011, and the attending sprinted through 80 slides then left for a meeting. Technically a lecture happened. Education did not.

Newer community programs—especially ones created by systems that actually care about resident recruitment—often:

- Hire faculty specifically for teaching and clinical excellence

- Have fewer fellows, so attendings and residents work together more closely

- Run smaller conferences with actual discussion instead of 60‑person passive PowerPoints

- Adapt faster because they don’t have 40 years of “we’ve always done it this way” blocking change

The single best predictor of your learning is not the building’s logo. It’s how much direct, thoughtful feedback you get from people who actually watch you work.

Academic ≠ better teaching. Community ≠ worse teaching. It’s specific people and structures, not categories.

Myth #4: New Community Programs = Career Dead-End

This one scares applicants the most: “If I don’t go academic, I’ll never get a fellowship / job / academic appointment.”

Here’s the actual pattern I keep seeing in real match lists and alumni trajectories:

Competitive fellowships absolutely take residents from strong community programs—especially if they see:

- Solid board scores

- Strong letters from known faculty

- Heavy clinical exposure

- Research or QI that’s relevant, even if it’s not in JAMA

Many academic departments prefer residents who trained in high-autonomy environments because they hit the ground running as fellows. I’ve heard variations of: “Our best cardiology fellows last year were from X community IM program; they know how to run a service.”

Your first job cares about:

- Board certification

- References

- Procedural competence / clinical reputation

- Personality and reliability

Much more than whether your residency was “academic” vs “community.”

| Outcome | Old Academic Program | Strong Community Program |

|---|---|---|

| Board pass rate | High to variable | Often high (pressure to prove) |

| Fellowship placement | Strong, established | Increasingly strong if well-run |

| First job options | Wide | Wide, especially local/regional |

| Research opportunities | Abundant | Targeted but sufficient |

| Autonomy | Often less (fellows) | Often more (resident-driven) |

The real trap isn’t “community.” It’s weak programs—of any type—that graduate under-prepared residents with spotty evaluations and poor reputations in their region.

A powerful but uncomfortable truth: a strong new community program in a large health system can open more practical doors than a mid-tier academic name with weak clinical training.

Myth #5: New Programs Are Inherently Unsafe Guinea-Pig Experiments

There’s some truth baked in here. Being in the first 1–3 classes of a brand-new program is riskier. Systems are immature. There are growing pains. You do some of the trailblazing.

But “new program” doesn’t automatically mean “chaotic and unsafe.” The relevant question is: How was this thing built, and who’s backing it?

Look hard at:

Sponsoring institution: Is it a large health system with established GME infrastructure, or a small hospital trying residency for the first time to fill coverage gaps?

Leadership track record: Has the PD/APD previously run or helped build other successful programs? Do they have a history of ACGME compliance and strong outcomes?

Protected time and resources: Is there real money behind education—coordinators, simulation lab access, conference time—or just lip service?

Case volume and services: Are residents covering a busy ED, ICU, and core inpatient services? Or are they scraping by to find enough patients?

The ACGME does not hand out initial accreditation like candy. New programs get frequent site visits and more intense monitoring for exactly this reason: there’s justified caution. But once a program starts graduating residents, their board pass rates and case logs start doing the talking.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | See New Program |

| Step 2 | High risk - be cautious |

| Step 3 | Potentially strong training |

| Step 4 | Weak exposure - red flag |

| Step 5 | Review board pass goals and support |

| Step 6 | Large health system sponsor |

| Step 7 | Experienced PD and APD |

| Step 8 | Strong volume and services |

The “guinea pig” experience can actually be a career advantage if the program is serious: you’ll get leadership roles, committee experience, and a say in building systems you can talk about for the rest of your career.

If the program is sloppy and driven purely by staffing needs? Run.

Myth #6: Academic Patients Are “More Interesting”

You hear students say this all the time. “I want interesting pathology, so I’ll go academic.”

Let’s be blunt. Your job as a resident is not to be constantly entertained by rare diseases. It’s to become frighteningly competent at the 95% of problems you’ll see every week, and solidly capable with the 5% that can kill people fast.

“Interesting” in training should mean:

- You’re pushed to your edge of comfort, not past it

- You have enough repetition to consolidate skills

- You see how common problems look in different bodies and social contexts

- You experience real-world constraints: lack of insurance, bad follow-up, limited resources

That last part is where many community and safety‑net hospitals absolutely crush. You’ll see medicine as it’s actually practiced in the United States, not inside a tertiary care bubble where every patient has multiple subspecialists and a case manager.

I’ve watched trainees from hyper-specialized academic bubbles struggle in their first job because they’ve never had to manage undifferentiated chest pain in a resource-limited setting without ten consultants to bail them out.

“Interesting” isn’t just about rarity. It’s about complexity in context. Community programs, especially those serving mixed or underserved populations, deliver plenty of that.

What Actually Predicts Training Quality (Regardless of Label)

Strip away the branding and mythology. When I look at whether a program—new or old, community or academic—is going to train solid physicians, I focus on a short list:

Resident autonomy with backup

Are you writing the notes, calling the shots, doing the procedures—with attendings close enough to keep things safe? Or are you a scribe for fellows?Case volume and diversity

How many patients and procedures per resident? What does the typical call shift actually look like?Culture of feedback and accountability

Do attendings and seniors actually watch you work and give specific, sometimes uncomfortable feedback? Or do they sign forms and move on?Program responsiveness

When residents raise problems, does leadership fix things within months or let them fester for years? Newer programs sometimes excel here because they must.Outcomes data

Board pass rates, in‑training scores, fellowship match, and what graduates actually do with their careers.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Resident autonomy | 90 |

| Case volume/diversity | 85 |

| Feedback culture | 80 |

| Program responsiveness | 70 |

| Program age | 20 |

| Academic vs community label | 10 |

Notice what’s near the bottom: “program age” and “academic vs community” as a label. They’re proxies, and increasingly lousy ones.

How You Should Actually Compare Programs

When you’re staring at ERAS lists or interview invites, don’t ask, “Is this academic or community?” Ask better questions:

- Who actually sees the patients—residents, fellows, or attendings?

- How many of X procedure or Y type of patient will I personally see by graduation?

- What do recent grads do? Pull their names and look them up.

- How do residents talk when they’re not in front of the PD? Listen in the work room, not just at the scripted lunch.

- When something goes wrong—a resident struggling, a rotation disaster—what happened next?

If a new community program checks those boxes better than an old academic one, don’t be a snob. Rank it higher.

The Real Myth: That There’s One “Safe” Path

The fixation on old academic programs is about fear. Fear that if you bet on something newer or less prestigious, you’ll wreck your future.

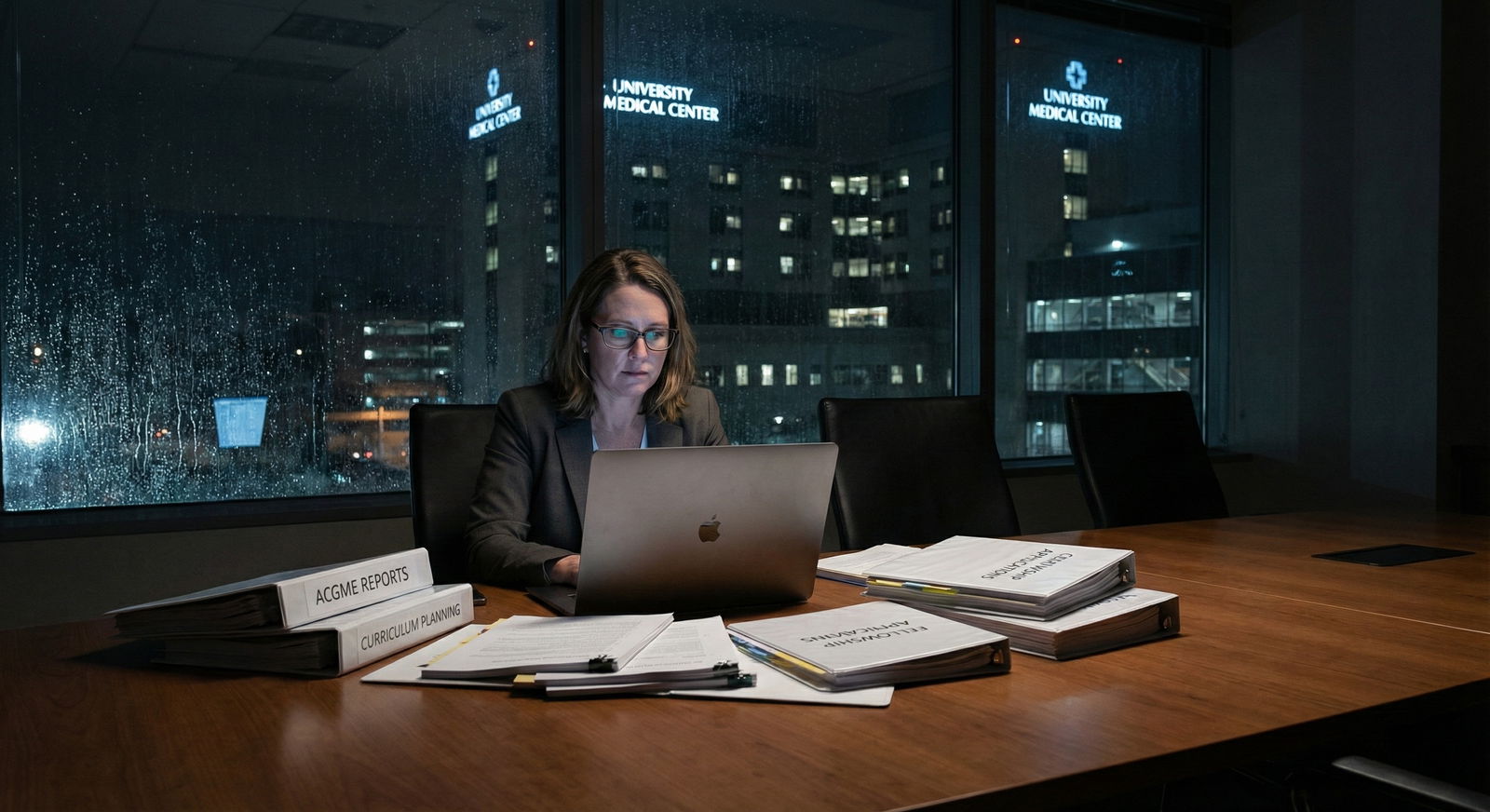

Here’s the truth that no glossy brochure or name-brand institution will say out loud: your training is shaped more by your day‑to‑day work, the people around you, and your own engagement than by the date on a charter or the word “university” on a sign.

Some of the best, most capable, unflappable physicians I know trained at what most MS4s would have dismissed as “just a community program.” They saw a ton of patients, had real responsibility, were pushed hard but supported, and walked out ready to practice. Their patients do not care what their program’s founding year was. Their outcomes don’t either.

Years from now, you will not remember the marketing language on a residency website; you’ll remember the nights you were scared, the attendings who showed up, and the places that actually taught you how to be a doctor. Choose the program—new or old, community or academic—that will give you more of those moments, not just a name you recognize.