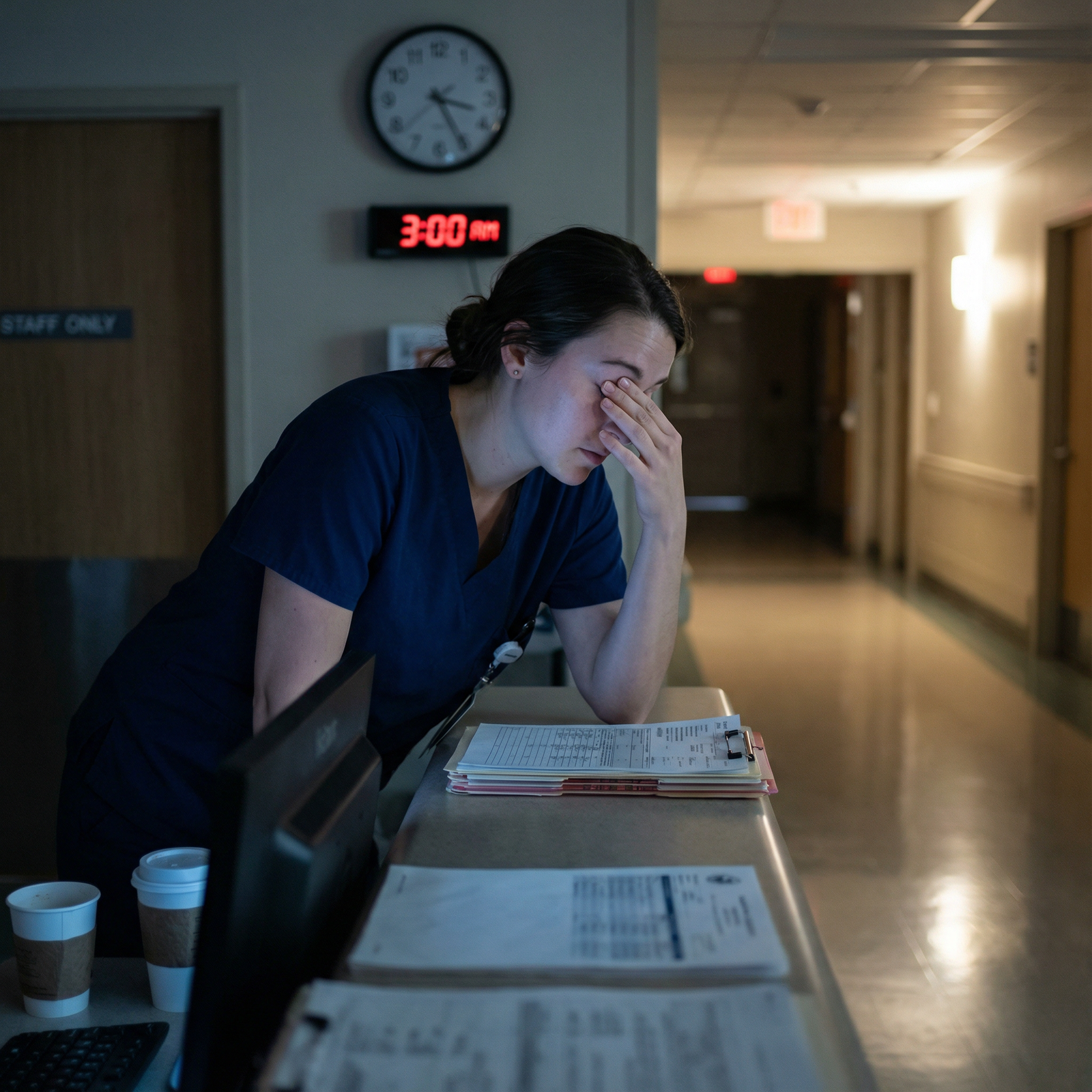

The way most programs throw residents onto solo night coverage is unsafe. For patients and for you. But you are the one in the building at 3 a.m., so you need a system that actually works when everything hits at once.

You cannot “just try your best” on these nights. You need structure, scripts, and hard rules. I am going to walk you through exactly how to run a night where you are the only resident covering multiple services without losing control or losing your license.

1. Before the Night Starts: Set the Chessboard

If you walk into a multi-service night shift without a plan, you are already behind. Your prep during sign-out determines how terrible 2–4 a.m. will be.

A. Get a ruthless sign-out (and control it)

Do not let sign-out be a vague story hour. You run it.

Ask each day team, for every service you cover:

“Who can actually crash?”

- “If I get only one page and it is about this service, who is it likely to be?”

- Flag:

- New admits with borderline vitals

- Patients on high oxygen needs, pressors, or new GI bleed / sepsis / DKA / NSTEMI

- Anyone with “we’re watching this trend” (lactate rising, creatinine climbing, troponins changing)

“What are the three things you’re worried about tonight?”

- Force them to commit:

- “Bed 12 – alcohol withdrawal, already tachycardic”

- “Bed 5 – possible upper GI bleed, hemoglobin dropped from 9 to 7.8, type and screen done”

- “Bed 20 – brittle COPD, just weaned from BiPAP”

- Force them to commit:

“What can I ignore or defer?”

- Chronic constipation in a stable patient

- Chronic hyponatremia with a plan

- “Family would like an update on prognosis” – that is day team work

- Get explicit permission: “If family calls overnight, OK to tell them the primary team will update in the morning?”

Get concrete contingency plans

- Do not accept “Call us if they get worse.”

- Push for: “If SBP < 90, give 500 mL LR, repeat BP, if still low start peripheral norepinephrine and call ICU fellow.”

- For chest pain: “If chest pain returns, repeat EKG, troponin, give SL nitro if BP > 100, page cardiology fellow if EKG changes or ongoing pain.”

Write this somewhere you will actually see it at 3 a.m. Not buried in an EMR tab.

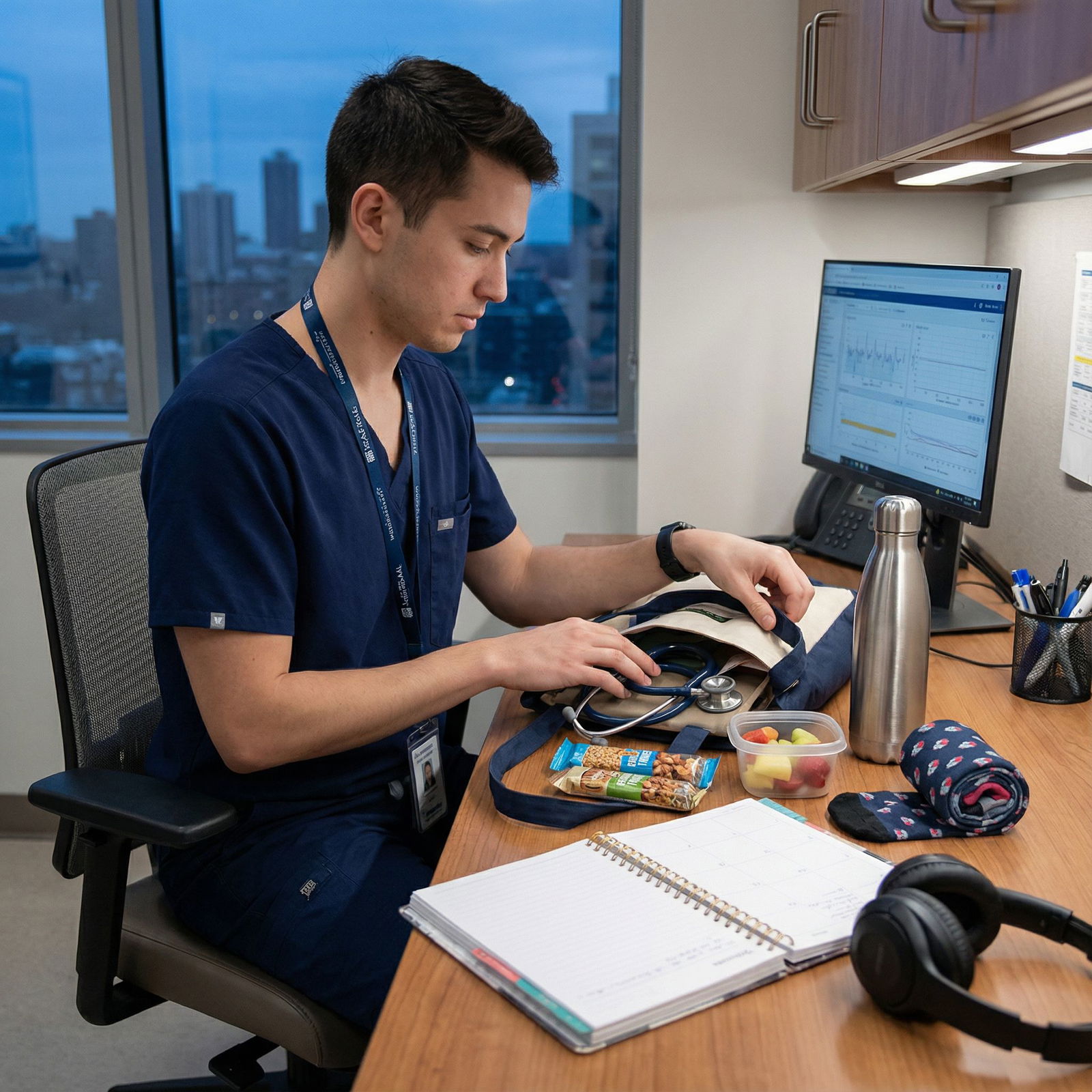

B. Build your “at-risk list” before they leave

Make a simple list (paper or digital, but visible):

- Column 1: Patient name / bed

- Column 2: Service

- Column 3: Problem

- Column 4: “If X then Y” contingency

Example:

| Patient / Bed | Service | Main Risk | Contingency Plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smith / 12B | Medicine | Sepsis, soft BP | Bolus 500 LR if SBP < 90; start norepi if MAP < 65 after 2 L; page ICU fellow |

| Lopez / 5C | GI | GI bleed | Transfuse if Hgb < 7 or hypotensive; call GI fellow if melena increases |

| Chan / 20A | Pulm | COPD, weaning O2 | If sat < 88% on 6L, start BiPAP and call Pulm fellow |

You are trying to convert night chaos into a checklist you can scan in 10 seconds.

C. Clarify backup and escalation

You need to know, clearly:

- Which attendings/fellows you can call:

- Medicine / Surgery / ICU / OB / Anesthesia / Cardiology, etc.

- How they want to be called:

- “Text page for routine issues, call directly for airway/unstable vitals.”

- Where the ICU team physically is after hours.

- Who runs codes and rapid responses.

Ask bluntly at the start of the rotation if you have not been told:

- “I will be the only resident covering X, Y, and Z at night. In a simultaneous decompensation, who do you expect me to call and what gets priority?”

If no one answers clearly, you decide your own priority hierarchy (I will give you one shortly) and stick to it.

2. Organizing the Night: Time, Tasks, and Triage

Nights fall apart when you react to every page as equal. They are not equal.

A. Create an opening “rounds” routine

First 60–90 minutes:

- Look at your at-risk list.

- Do quick chart checks on those patients:

- Most recent vitals

- Latest labs

- New nursing notes

- For anyone “red flag,” see them early:

- Borderline vitals

- High oxygen needs

- New transfusion

- New BiPAP

- Rapid AFib

- Put in prophylactic orders if needed:

- PRN antiemetics, sleep meds, pain meds

- Sliding scale insulin if missing

- Bowel regimen if they are already complaining and you know they will call at 3 a.m.

You are front-loading stability and reducing future pages. This is not optional on multi-service nights. It is survival.

B. Use a strict triage framework

When you are hit with multiple pages:

- Code Blue / airway / unresponsive

- Rapid response criteria (acute change in mental status, SBP < 90, RR > 30, O2 sat < 90% on high-flow)

- Uncontrolled pain, severe agitation, acute bleeding, new chest pain, status epilepticus

- “Mild but urgent” – increasing O2 needs, rising fever in neutropenic patient, borderline vitals

- “Annoying but safe” – sleep meds, constipation, chronic pain, “family has questions,” diet change

You do not handle these in the order paged. You re-sort them in your head or on paper:

- Life-threatening – go now, physically if possible.

- Potentially unstable – call nurse, get vitals, put in stat labs, plan to see next.

- Symptomatic but stable – can be addressed after the above.

- Non-urgent – batch and handle in one EMR session every 30–60 minutes.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Life-threatening | 10 |

| Potentially unstable | 25 |

| Symptomatic but stable | 35 |

| Non-urgent | 30 |

You will feel guilty about the non-urgent delays. You will have to tolerate that. Your job is to keep people alive first.

C. Use a real-time task board

Do not trust your 3 a.m. brain.

Make a running list with:

- Time of page

- Patient / bed

- Brief issue

- Priority (1–4 as above)

- Status: “To see”, “Orders placed”, “Seen”

Something like:

- 22:15 – 8A – chest pain – Priority 1 – going now

- 22:20 – 11C – melena, unchanged vitals – Priority 2 – labs ordered, see after 8A

- 22:22 – 4B – wants Ambien – Priority 4 – batch later

Even a scrap sheet works. It prevents dropped balls and helps when charge nurse asks “Have you seen 11C yet?”

3. Page Management: Scripts That Save Your Brain

Most residents waste time on the phone. They either let nurses give long narratives or they get stuck in circular conversations.

You need structure.

A. Standard 30-second nurse script

You can teach this script explicitly to recurrent night nurses. Many already use some version:

- “Tell me:

- Who is the patient?

- What is the main problem right now?

- What are the current vitals?

- What have you already done?”

If they start telling you the entire hospital course, cut in politely but firmly:

- “Sorry to interrupt, can you give me the most recent vitals and what is happening right now?”

You are not being rude. You are being safe.

B. Your response structure

For each call, your mental checklist:

Stability check

- “Is the patient awake and talking?”

- “What are their last vitals?”

- “Are they on monitors / supplemental O2?”

Decide: phone orders vs bedside

- If any doubt about stability: “I am coming to see the patient now. Put them on the monitor, get a full set of vitals, and draw stat [labs] if possible.”

Give specific orders

- Time-limited, dose-specific.

- “Give morphine 2 mg IV now, OK to repeat once in 30 minutes if pain still > 7 and RR > 10.”

Close the loop

- “If [X] happens, call me back immediately.”

- Example: “If SBP < 90 or HR > 130, call me back right away.”

You must stop vague “Call me if they get worse.”

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Page received |

| Step 2 | Ask for vitals and problem |

| Step 3 | Go to bedside now |

| Step 4 | Give phone orders |

| Step 5 | Define call back triggers |

| Step 6 | Assess, order tests, treat |

| Step 7 | Stable? |

| Step 8 | Needs exam? |

4. Handling Simultaneous Crises

This is where people crack. Two sick patients, one you. There is no clean solution, just less-dangerous ones.

A. Use a fixed priority rule

When truly simultaneous:

- Immediate life threats

- Airway compromise

- Code Blue / pulselessness

- Unresponsive patient

- Shock / severe respiratory distress

- SBP < 80

- O2 sat < 85% on high O2

- Serious but breathing and with a pulse

- Active GI bleed but awake and talking

- DKA with stable airway

- Chest pain with normal vitals and no EKG changes

Between a hypotensive GI bleeder and a conscious chest pain with normal vitals, you go to the bleeder. Period.

B. Use other people in the building

You are not actually alone, even if you are the only resident.

- Call the charge nurse:

- “I have two urgent patients, I am going to bed 10 now. Can you send the most experienced nurse to bed 3, put them on full monitor, get vitals and an EKG, and I will come as soon as I can.”

- Call the ICU / rapid response nurse if your hospital has one:

- They can start the initial resuscitation while you are tied up.

- For potential airway:

- Call anesthesia early: “This could go bad; I want you aware and nearby now, not after they crash.”

The dumbest thing I see interns do: try to be the only one touching either patient until they finish. Use the team resources.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Charge nurse | 90 |

| Rapid response team | 75 |

| ICU fellow | 70 |

| Anesthesia | 65 |

| Primary attending | 40 |

(Values represent approximate usefulness for immediate bedside help at 3 a.m., not theoretical hierarchy.)

C. Document your judgment

When you have to choose, chart a one-liner later:

- “At 03:15 simultaneously paged for hypotension in 10B and chest pain in 3A. Prioritized hypotensive patient per hospital protocol and requested nursing to obtain EKG and vitals in 3A pending my evaluation.”

You are protecting yourself. And you are telling the truth.

5. Protocols for Common Night Problems

You do not have time to rethink constipation or insomnia at 4 a.m. Have stock approaches.

A. Pain

For stable patients with known pain issues:

- Check:

- Vitals

- Allergies

- Renal/hepatic function

- Mild–moderate:

- PO options first if GI tract working

- Severe:

- Small IV doses, reassess

- Order rescue:

- “If pain > 7 after PO, OK for 1 dose IV.”

Avoid building brand-new pain regimens at 3 a.m. if you can defer to day team.

B. Chest pain

Even on non-cardiac services, act like this:

- Tell nurse:

- Full vitals

- 12-lead EKG

- O2 if sat < 94%

- Ask yourself:

- Does this sound like typical angina? Any risk factors?

- Orders while you are walking there:

- Troponin

- Basic labs if not recent

- If concerning EKG changes or ongoing pain:

- Call cardiology fellow or on-call attending

- Consider ASA (if not already on), nitro if BP allows

Do not blow this off as “anxiety” until you have data.

C. Shortness of breath

Your immediate questions:

- “What are the sats now and 15 minutes ago?”

- “What is the O2 delivery and how has it changed?”

- “Lung sounds? Crackles, wheezes?”

On the way:

- Order stat CXR, ABG/VBG if severe, consider BNP, D-dimer if appropriate.

- For known COPD with wheezing: bronchodilators, steroids if not already on.

- For possible fluid overload: consider diuretics if safe and known heart failure.

If O2 requirements escalate rapidly despite intervention: early ICU consult.

D. Agitation / delirium

Nights amplify delirium. You will get dozens of these.

Basic approach:

- Rule out:

- Hypoxia

- Hypoglycemia

- Big med timing errors (missed benzos in alcohol withdrawal, etc.)

- Non-drug first:

- Lights down, noise reduction, family call if they are local and appropriate

- If unsafe (pulling lines, trying to leave):

- Low-dose antipsychotic (haloperidol, olanzapine) per your hospital standard

- Avoid benzos unless clear withdrawal or specific reason

- Call security / sitter if risk of harm

Document clearly that behavior was unsafe. Protects nursing, security, and you.

6. Protecting Yourself from Burnout and Blame

Covering multiple services alone at night will eat you alive if you let it. You must defend your brain and your license.

A. Set internal rules

Example personal rules that actually work:

- “No major new diagnoses at night unless life-threatening.”

- “If I need two or more doses of IV narcotics, I reassess in person.”

- “If two people tell me a patient looks bad, I go see them, even if vitals look OK.”

- “If I am considering a risky decision and I feel uneasy, I call the fellow/attending.”

Write your rules down. Hold yourself to them.

B. Use your attendings and fellows—this is not weakness

I have seen residents get in more trouble for not calling than for “bothering” someone at 3 a.m.

When to call without hesitation:

- Escalating pressor needs

- New need for BiPAP or high-flow O2

- Unexpected transfer to ICU

- CT findings that change management significantly

- Any time you are guessing about a high-risk decision

- “I am the only resident covering X, Y, and Z tonight. I have a patient with [brief story, vitals, what you have done]. I am worried about [specific concern]. I am considering [two options]. What do you recommend?”

They hear: you are organized, you have already thought, and you are not dumping mindlessly.

C. Document like future-you might get sued

You do not need novels. You need clear, defensible notes.

For major events:

- Time you were called

- What you were told

- What you found

- What you did

- Who you called

- Patient response

For example:

- “Called at 02:05 for hypotension in 8B. On arrival 02:10, BP 78/40, HR 120, alert but pale. Gave 1 L LR bolus, started norepinephrine via peripheral IV, blood cultures drawn, broad-spectrum antibiotics started per sepsis protocol. ICU fellow Dr. X notified at 02:20; accepted for transfer.”

If you had five fires at once, say that. Courts and review committees understand staffing reality better than you think.

7. Debrief and Improve: Do Not Repeat the Same Bad Night

The only thing worse than a brutal night is repeating the same mistakes every week.

A. Quick post-call review (even 10 minutes helps)

When you get home or before you leave:

Ask yourself:

- Which patients almost crashed that I did not expect?

- Which pages were a waste of time that I could have prevented with better sign-out or anticipatory orders?

- Which decisions felt shaky?

Write down 3 concrete changes for the next set of nights:

- “Add a standing order for sleep meds for Mrs. X at sign-out – she paged 4 times for it.”

- “Flag borderline O2 patients and see them earlier.”

- “Clarify with day team about DNR/DNI status on unclear patients before they leave.”

B. Talk honestly with your seniors or PD

Not with whining. With data.

Example conversation:

- “Last night I was solo covering 40 patients across medicine and neurology. Between 11 p.m. and 4 a.m. I had 48 pages, 3 rapid responses, and 1 ICU transfer. I prioritized airway and hypotension, but I had to delay seeing a chest pain patient by 30 minutes. I want to make sure my prioritization is aligned with your expectations, and I also wonder if we can standardize night sign-out to reduce non-urgent pages.”

Now you sound like a responsible physician pointing out a risk, not just complaining.

C. Build and share your own micro-protocols

If your program does not have night protocols, make your own 1–2 page cheat sheets:

- Chest pain algorithm

- SOB / hypoxia algorithm

- Delirium / agitation meds and doses

- “What to do before you call the ICU”

Share them with junior residents and nurses. Suddenly you are not just surviving nights; you are improving the system.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Night shift |

| Step 2 | Handle pages and crises |

| Step 3 | Post-call review |

| Step 4 | Identify 2-3 changes |

| Step 5 | Adjust sign-out and protocols |

| Step 6 | Communicate with team |

8. Mental Survival: Keeping Your Head When You Are Outnumbered

Being the only resident at night is not just a logistics problem. It is a psychological hit.

A. Accept that you cannot do everything perfectly

You will miss minor things. Someone will not get their preferred sleep med. Labs will be drawn late. A family member will be mad the doctor did not call them back at 2 a.m.

Let that go.

Your metric is not “zero complaints.” It is:

- No preventable deaths or major harm on your watch.

- You called for help when you were out of your depth.

- You acted systematically, not randomly.

B. Use small resets during the night

Even five minutes matter:

- After a code or major resuscitation:

- Step away, drink water, jot down what happened.

- Between bursts of pages:

- Sit, close your eyes for one minute, slow your breathing, then look at your task list again.

You are not a robot. If you try to be, you will make stupid mistakes at 4 a.m.

C. Have a post-night decompression ritual

Something predictable:

- Shower and truly wash the night off.

- 10 minutes of writing about the worst page and the best decision you made.

- Zero EMR or email after you leave.

Your brain needs a signal: “The shift is over now.”

Key Takeaways

- Multi-service nights cannot be winged. Aggressive sign-out, an at-risk list, and early rounds create the margin you need to survive 2–4 a.m.

- Triage relentlessly. Use a fixed priority system for pages and simultaneous crises, lean heavily on nurses and rapid response teams, and call attendings/fellows early for high-risk decisions.

- Protect yourself. Document your judgment, set personal safety rules, debrief after shifts, and turn each brutal night into a slightly better one by changing how you and your team approach the next one.