Cross-Cover on the Floors: A System for Handling 30+ Patients Overnight

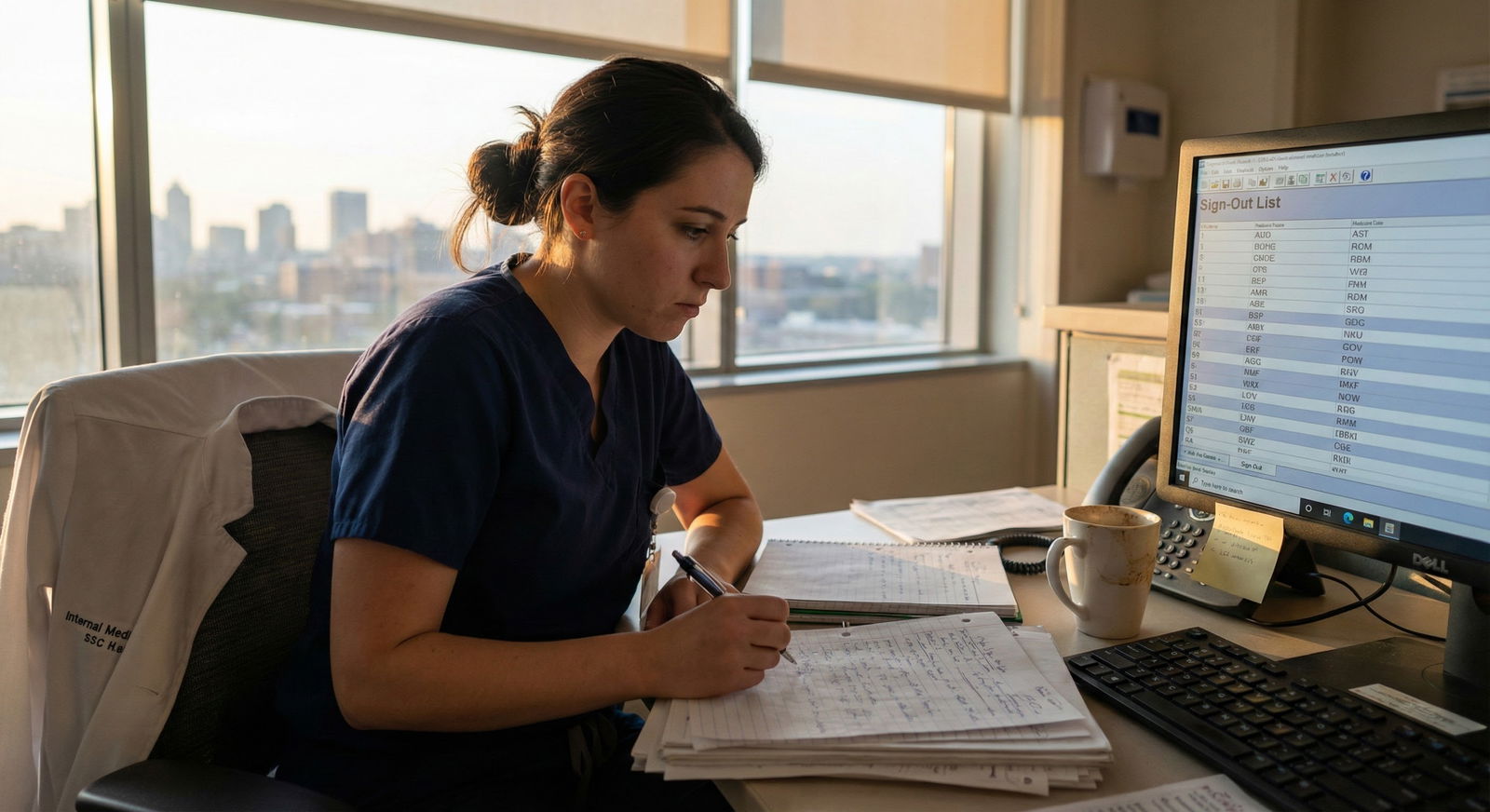

It is 6:52 p.m. Your day-call colleague just handed you a folded sign-out sheet that looks like a CVS receipt. Two teams. Thirty‑two patients. One cross-cover resident. The attending is home, the interns are gone, and the nurse at the far end of the hall is already waving at you about “just a quick order.”

If you try to “just hustle harder,” you will drown. If you use a system, you will get through this night (and the hundred after it) without missing the big stuff.

Let me break this down specifically.

1. Your Mental Model: What Cross-Cover Actually Is

Cross-cover is not “being the on-call superhero.” It is providing safe, temporary stewardship of other people’s patients for 12 hours.

You are not there to:

- Re‑do the entire day team’s work

- Completely re‑work diagnoses at 3 a.m. for stable issues

- Make heroes’ moves that blow up the day team’s plans

You are there to:

- Prevent death and irreversible harm

- Stabilize enough for the day team to reassess

- Handle predictable “night shift” issues efficiently

So your default move is: recognize pattern → stabilize → leave a clear note for day team. Heroics are rare. Pattern recognition and triage are everything.

2. Before Sign‑Out: Set Up Your System, Not Just Your Coffee

The hour from 6–7 p.m. is where most night shifts are either saved or destroyed.

A. Create your “control screen”

Do not just open “the list” and call it a day. You need a cockpit view.

Minimum:

- One screen (or window) with the active patients list

- One with recent labs/imaging

- One with messages/pages/notifications

If your EMR allows custom columns, add:

- Code status

- Level of care (floor/stepdown)

- Primary problem (even if it is crude: “DKA,” “sepsis,” “NSTEMI”)

- “Watcher” flag for high-risk patients

If your system is primitive, you make your own:

- Printed list with: name, room, age, major diagnoses, code status, key overnight concerns, and a checkbox column

- Color‑code or mark: circle rooms with high risk (borderline pressors, oxygen ≥ 4 L, new GI bleed today, etc.)

You are building a map of the battlefield, not just a list of names.

B. Pre‑round your sign‑out

When teams give you sign‑out, you should already know who you care about.

Scan:

- Latest vitals trend: any soft hypotension, tachycardia, O2 creeping up

- Labs from the afternoon: new uptrending creatinine, dropping Hgb, weird troponin pattern

- Current med list: heparin gtt, insulin gtt, vasodilators, anticoagulants, high-risk QT-prolongers

Tag 5–10 patients as “must know cold.” These are your:

- Fresh admissions (last 4–6 hours)

- Anyone transferred from ICU within 24–48 hours

- Active bleed, active arrhythmia, active sepsis

- Any patient on a titratable drip on the floor (never a good sign)

C. Demand usable sign‑out

Bad sign‑out kills more patients than caffeine shortage ever did.

You want:

- One‑liner: “Mr. X, 68, COPD, admitted with pneumonia and septic shock, now stable on 2 L O2.”

- Active issues: “Watch BP, was 90s systolic this afternoon; trending up. Recheck BMP at 04:00, follow lactate.”

- Clear contingency plans: “If sats < 88% on 4 L, call RRT and consider transfer.”

Cut off rambling. “What do you actually want me to do if things go wrong?” is a fair question.

If the sign‑out is vague on a high-risk patient, open the chart while they are still in front of you and ask pointedly:

“What if his pressure drops again?”

“What if she desats?”

“Any limiting factors on escalation? DNI? DNR?”

You are not being annoying. You are doing safety.

3. The Hierarchy of Overnight Problems: A Triage Lens

Cross‑cover is 90% pattern recognition. The same problems over and over: pain, blood pressure, fever, hypoxia, mental status, urine output, “the nurse is worried.”

You need a mental triage pyramid. Mine looks like this:

- Airway and breathing

- Circulation (BP, perfusion, obvious bleeding)

- Mental status change

- Dangerous electrolytes/metabolic issues

- Uncontrolled pain, agitation, nausea

- Everything else

If you are staring at a full inbox of pages, you must internally stack them against this hierarchy.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Pain/PRNs | 35 |

| BP/HR | 20 |

| Fever | 15 |

| Hypoxia | 10 |

| Labs/Orders | 10 |

| Mental Status | 10 |

You respond in order of time‑sensitivity, not order of arrival, not who sounds angriest on the phone.

4. A Practical Incoming Page Algorithm

The resident who survives nights does not pick up the phone and wing it. They run the same internal script every time.

Step 1: When paged, get a usable one‑liner

If you call back and hear, “Your patient does not look good,” that is useless.

You ask, calmly, in this order:

- “Which patient, and where are you now?”

- “What is the main concern in one sentence?”

- “What are the current vitals?”

- “How do they look compared to baseline today?”

If the nurse is at the bedside, have them read the vitals off the monitor. If they are not, ask them to go and call you back with vitals unless it is obviously an emergency.

Then you classify:

- Critical – Go now, bring stethoscope, maybe call RRT on your way.

- Urgent – Go in the next 5–10 minutes, after you finish what you are literally doing.

- Routine – You can handle by order/message/chart review, often without immediate bedside evaluation.

Step 2: Decide on location of response

For each page, you ask yourself: “Is this a phone problem or a bedside problem?”

Phone problems (with chart review):

- PRN pain order within defined limits

- Insulin sliding scale dosing question

- Clarifying home medication lists

- Adjusting timing of non‑critical labs

- Changing diet to NPO for a procedure in the morning

Bedside problems:

- Any change in respiratory status beyond “needs nasal cannula at night”

- SBP < 90 or MAP < 60, or big drop from baseline

- New confusion or acute change in mental status

- New chest pain, sudden severe headache, focal neuro signs

- Significant bleeding (melena, hematemesis, hemoptysis, large hematoma)

If you hesitate between phone vs. bedside, go see the patient. You will never regret laying eyes on someone who is truly sick. You will eventually regret not doing it.

Step 3: Batch non‑urgent issues

This is how you survive 30+ patients.

As you get routine pages (mild pain, nausea, sleep meds, constipation, lab timing), do not drop everything each time to open and close the chart fully.

You:

- Acknowledge: “I will put in an order, it may take a few minutes.”

- Jot it on a small scratch list or use your “to‑do” column in EMR.

- Batch every 3–5 minor issues into one ordering session.

You are reducing “context switching.” Your brain is not meant to re‑orient fully 200 times a night. You will miss something if you try.

5. High‑Yield Scenarios: What to Actually Do, Not Just Think

Now the things that make or break nights: the patterns that come up constantly.

A. Hypotension on the floor

Page: “BP is 82/46, HR 112. Patient looks a bit pale.”

Your internal script:

- Go to bedside.

- While you walk, think: sepsis, bleeding, cardiogenic, medication effect, volume depletion.

- On arrival: ABCs first. Is the patient talking in full sentences? Is mentation intact? Skin warm or cold? Diaphoretic?

Focused exam:

- Heart, lungs, JVP, abdomen, extremities for edema or bleeding

- Check lines, drains, dressings, Foley output

Immediate moves:

- Recheck BP manually. Automated cuffs lie, especially on thin or edematous arms.

- Call RRT if they look bad, are altered, or have SBP < 80 repeatedly. Do not try to “fix it yourself” while they circle the drain.

- If likely hypovolemia: fluid bolus (e.g., 500–1000 mL LR/NS), unless they are in florid pulmonary edema.

- Check stat labs: CBC, BMP, lactate, maybe troponin if chest pain or cardiogenic suspicion.

Avoid:

- Random “just a little more antihypertensive” if they were on aggressive BP meds. This is how people end up in the unit.

- Ignoring borderline lows because “they were 90s this afternoon.” Trends matter.

Leave a clear note: what you saw, what you thought, what you did, what you want day team to follow up.

B. Hypoxia

Page: “O2 sat 86% on 2 L. Increased to 4 L, now 90%.”

Again: this is a bedside problem. No exceptions.

At bedside:

- Is airway protected? Talking in full sentences or single words?

- Accessory muscle use? RR > 30? Cyanosis?

- Listen: new crackles, wheezing, absent breath sounds, asymmetric findings.

Immediate interventions:

- Sit them upright.

- Adjust supplemental O2 carefully; if jumping from 2 L to 6 L, you need to be thinking “RRT soon” not “good, problem solved.”

- If COPD or CO2 retainer, still treat hypoxia first. You will not fix chronic hypercapnia overnight, but you can absolutely kill someone by ignoring hypoxia.

Imaging/labs:

- If new: stat CXR.

- If concern for PE: consider CTA chest (if stable enough, discuss with senior).

- If CHF suspicion: CXR, consider IV diuresis (if not hypotensive, kidneys tolerable).

Threshold for RRT/ICU consult:

- Need > 6 L to keep sats > 92% (or > 88% in known COPD)

- RR > 30 with work of breathing

- Altered, cannot protect airway

You can escalate oxygen, but you must escalate level of care in parallel if requirements are climbing.

C. Fever

Page: “Your patient is 38.8°C, otherwise stable.”

Do not knee‑jerk “pan‑culture and broad‑spectrum antibiotics” on everyone, or you will torch kidneys and create C. diff.

Ask:

- “What are the other vitals?” If HR, BP stable and patient looks okay, you have room to think.

- “Any new localizing symptoms? Cough, dysuria, abdominal pain, wound issues?”

Chart review:

- How long have they been here? Day 1 pneumonia vs post‑op day 2 vs day 15 with central line?

- Current antibiotic regimen, if any.

- Neutropenic? (ANC, chemo history)

Reasonable plan for a stable, non‑toxic floor patient:

- Full set of vitals, repeat temp in 1–2 hours.

- Basic labs: CBC, BMP, maybe lactate if suspicious of sepsis.

- Cultures and imaging guided by context (UA + culture if urinary symptoms; CXR if new cough/hypoxia; blood cultures if septic appearing).

- Antipyretic: acetaminophen, unless contraindicated.

Escalate fast if:

- Hypotensive, tachycardic > 120–130, tachypneic, altered, or rigors with chills.

- Immunocompromised (transplant, on high‑dose steroids, recent chemo). These you treat and escalate aggressively, often with broad‑spectrum antibiotics and RRT/ICU consult early.

D. Chest pain

Nightmare scenario in sign‑out: “Has chronic atypical chest pain.” Translation: you will get paged.

At bedside:

- Character: pressure vs sharp vs pleuritic, radiation, associated SOB, diaphoresis, nausea, exertional correlation.

- Immediate vitals, continuous monitoring.

- Brief exam: heart, lungs, HF signs, chest wall tenderness, murmurs.

Immediate workup:

- Stat EKG (non‑negotiable).

- Troponin.

- If classic ischemic symptoms or dynamic EKG changes: call RRT or cardiology depending on local culture; start ACS protocol per hospital policy (aspirin, nitrates if no hypotension, etc.).

If EKG unchanged, troponin negative, pain reproducible, vitals rock solid — you can treat symptomatically and sign out the story clearly for day team to consider further workup.

E. Acute mental status change

Most dangerous page that often gets minimized: “Patient is a little more confused.”

You have 5 buckets in your head: hypoxia, infection, metabolic (glucose/electrolytes), drugs/sedatives, structural (stroke, bleed).

At bedside:

- Check ABCs, vitals, fingerstick glucose.

- Look at pupils, unilateral weakness, facial droop, pronator drift.

- Review MAR: Did someone just give benzo, opioid, anticholinergic, gabapentin, or diphenhydramine?

Immediate orders:

- Fingerstick glucose (if not already done).

- BMP, CBC, LFTs, ammonia if hepatic history, UA, CXR if infection suspected.

- Consider CT head urgently if ANY focal neuro or high concern for acute bleed or stroke.

If this is “quiet, very sleepy, hard to arouse” 30 minutes after IV dilaudid in an opioid‑naïve person, do not overcomplicate it. You support airway, give naloxone if borderline, and monitor in an appropriate setting.

6. Managing the Volume: Time, Geography, and Documentation

A. Move like a floor general, not a Roomba

If you are covering multiple units or floors, plan intentional “sweeps.”

Example:

- After sign‑out, walk through high‑risk rooms first (your mental top 5–10). Quick eyeball: are they still okay?

- When you get called to one end of the floor, check in on another nearby patient with a known active issue (slow bleed, borderline BP) before heading back.

Group your work by geography when safe.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Receive Sign out |

| Step 2 | Identify High Risk Patients |

| Step 3 | Set Up Lists and Flags |

| Step 4 | First Safety Sweep |

| Step 5 | Go To Bedside Now |

| Step 6 | Complete Current Task Then Bedside |

| Step 7 | Batch For Later Orders |

| Step 8 | Stabilize and Document |

| Step 9 | Order Entry Block |

| Step 10 | Page Received |

You do not wander randomly from call to call. You control the path as much as possible.

B. Documentation: Enough to protect you, not enough to bury you

For big events — hypotension, acute desat, RRT call, new arrhythmia — you write a focused note:

- Reason you were called

- Brief exam and vitals

- Assessment (your best hypothesis, even if “unclear, but…” is the answer)

- Interventions done (fluids, O2, labs, meds, escalation)

- Disposition / plan for day team (“will need repeat Hgb at 08:00,” “consider formal echo,” etc.)

This takes 3–5 minutes and saves you in M&M and protects the patient’s continuity of care.

For routine stuff (Tylenol for headache, one‑off Zofran, sliding scale insulin), you do not need a novel. Rely on orders and maybe a brief EMR “telephone encounter” or problem‑based comment depending on your institution.

C. Use templates and order sets ruthlessly

You do not have time to custom‑build every sepsis workup at 3 a.m.

- Save personal “favorites” in EMR: sepsis labs bundle, chest pain set, delirium workup, hypoxia bundle.

- Know the hospital’s standardized order sets cold and use them instead of reinventing the wheel.

This is not laziness. It is error reduction.

7. Communicating With Nurses: Your Lifeline During Cross‑Cover

You can either treat nurses as “people who page you,” or you can treat them as your overnight sensory system. The second approach will make your nights safer and your life easier.

A. Establish tone early

At the start of the shift, if there is a unit you know you will cover heavily, walk by the main station:

- “I am covering teams A and B tonight. If a patient looks worse than they should, please call me early rather than late.”

It shows you are approachable and gives them permission to call for “gut feeling” issues. These are the calls that save patients before they crash.

B. Make expectations clear, gently

If you get paged 5 times in 20 minutes about minor non‑urgent things, it is often because no one ever set boundaries.

You can say:

“I will absolutely put in that sleep med. I am handling a hypotensive patient right now, so it might take 15–20 minutes. If anything changes, please call me back.”

You just told them:

- You take serious things seriously.

- You are not sitting on your hands ignoring their request.

- They should re‑page only if there is real change.

C. Listen when an experienced nurse says “I am worried”

I have seen more subtle GI bleeds, early sepsis, and impending respiratory failures caught by a nurse saying “He just does not look right” than by any lab value. Go look. Even if their vitals are technically “fine.”

8. Protecting Your Brain: Cognitive Load Management

This part nobody teaches, but it is the difference between being merely tired and being unsafe.

| Problem | Practical Fix |

|---|---|

| Constant context switching | Batch orders and pages |

| Holding tasks in your head | Externalize with a small task list |

| Disorganized note-taking | Use simple, repeatable templates |

| Decision fatigue on small stuff | Default protocols and order sets |

A. Externalize your working memory

Do not trust your brain at 3:45 a.m. to remember “check that 2 a.m. Hgb” or “reassess that patient after the fluid bolus.”

Use:

- A mini checklist on your sign‑out sheet

- A simple text note in EMR with time‑stamped tasks

- Phone reminders if needed (HIPAA‑compliant, obviously: “2:00 — recheck BP 834B” is usually fine)

If you keep tasks in your head, you will forget one sooner or later. And it will be the important one.

B. Use micro‑breaks strategically

You do not need a 20‑minute nap. You do need 90 seconds where you are not looking at screens or talking.

Every hour or two, if things are not crashing:

- Stand in a quiet corner.

- Close your eyes, breathe deeply 5–10 cycles.

- Roll your shoulders, stretch your neck.

You are trying to reset just enough to not be a zombie. That is it.

C. Know your personal failure modes

Some residents, when stressed, over‑order everything. Every fever gets a pan‑scan and 4 cultures. Others under‑react and try to “watch and wait” on clearly sick patients.

Figure out your reflex pattern and consciously correct:

- If you are an over‑tester: pause 10 seconds before clicking; ask, “Will this test actually change what I do tonight?”

- If you tend to under‑act: practice saying, “I am going to err on the side of doing more, not less, for this one.”

9. Typical Night Timeline: A Realistic Sketch

Every hospital is different, but nights on cross‑cover often follow a recognizable arc.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 19:00 | 70 |

| 21:00 | 55 |

| 23:00 | 40 |

| 01:00 | 35 |

| 03:00 | 50 |

| 05:00 | 65 |

19:00–21:00 – The Chaos Hour

- Sign‑out overload.

- Multiple pending issues from the day team: blood transfusions finishing, late imaging, first post‑op checks.

- Pain control, nausea, evening insulin questions.

Your job: stabilize the list, see the known sick patients early, and aggressively clarify plans.

21:00–01:00 – The Pattern Phase

- Less new admissions, more “hey can I get melatonin/Trazodone” pages.

- Fevers begin to declare themselves.

- Nurses complete evening med passes and really see who “looks off.”

Your job: batch the non‑urgent stuff, thoroughly evaluate the one or two concerning changes, and avoid getting sucked into long bedside conversations unless necessary.

01:00–04:00 – The Vulnerable Window

- Your brain is sluggish.

- Most code blues seem to happen “out of nowhere” in this time block, because subtle changes went unnoticed or unacted for hours.

- You are tempted to cut corners.

Your job: double‑down on vigilance for your known high‑risk patients. If you promised yourself a re‑check on someone, this is when it saves them.

04:00–07:00 – The Handoff Setup

- Early morning labs come back, revealing AKIs, dropping hemoglobins, rising troponins.

- Vitals for early surgeries, dialysis, and discharges get checked.

- Day team is on the horizon.

Your job: triage morning surprises. Decide what needs to be stabilized and what needs a clear sign‑out: “At 05:15, Cr was 2.1 up from 1.5, gave a fluid bolus, peed 400 mL since, needs repeat BMP by noon.”

10. When to Call for Backup — And When Not To

The insecure resident either never calls for help or calls for everything. Both are unsafe.

Reasonable triggers to call senior/attending at night

- Any time you are activating RRT or transferring to ICU and the patient is not “obviously” in one bucket (e.g., clear septic shock).

- Any unexpected deterioration in a patient who was supposed to be stable (post‑op day 3, routine cellulitis, etc.).

- Big decisions with irreversible consequences: stopping anticoagulation on a recent stent, initiating high‑risk meds, or making major code‑status shifts.

- Diagnostic uncertainty where multiple dangerous things are possible and you need another brain.

Phrase your call like this:

“Mr. X, 72, with COPD and CHF, admitted for pneumonia, now on 4 L O2. At 02:00 became more hypoxic to mid‑80s on 6 L, RR 30, new diffuse crackles. I have: examined him, given 40 mg IV lasix, obtained CXR that shows worsening pulmonary edema, called RRT, and they are evaluating him now. I think he needs ICU for BiPAP and closer monitoring. I am calling to loop you in and ask if there is anything else you would do differently.”

You are not calling to dump the problem. You are calling with data and a plan.

When not to call at 3 a.m.

- For routine, clearly non‑urgent issues already anticipated in sign‑out: constipation in a patient with a bowel regimen plan, routine sliding scale insulin, mild insomnia.

- For “FYI” only: save it for your handoff or a morning email/message.

You are expected to be a physician, not a human auto‑dialer.

11. Building the Skill Across Months, Not One Night

You will not master cross‑cover in three shifts. That is fine. The point is to move from chaos to pattern.

After each stretch of nights, do a 5‑minute debrief with yourself:

- Which 2–3 pages threw me the most?

- Did I miss any early warning signs that later declared themselves?

- What do I wish I had clarified at sign‑out?

Turn those into micro‑rules. For example:

- “Any patient transferred from ICU in the last 24 hours is automatically on my ‘early check’ list.”

- “Any fever in a neutropenic patient = immediate bedside evaluation and talk to senior.”

- “Any SBP < 90 repeated on two readings = I go see them, even if ‘they always run low.’”

Over time, these rules shrink your cognitive load and increase your safety margin.

Key Takeaways

- Cross‑cover is about triage and stabilization, not heroics. Build a deliberate system: good sign‑out, a control screen, a clear mental triage pyramid.

- Treat recurring overnight problems — hypotension, hypoxia, fever, chest pain, AMS — as pattern‑based scenarios with rehearsed scripts, and see sick patients with your own eyes.

- Protect your brain and your patients by batching non‑urgent tasks, documenting focused but real events, and using nurses and seniors as allies, not obstacles.