You just finished ICU orientation. You know where the code cart lives, you clicked through 40 PowerPoint slides on ARDS, and someone showed you how to put in vent orders in the EMR… once… at 3 p.m. when your brain was already mush.

Now your schedule says: “Nights. Starting tomorrow.”

No gradual ramp-up. No easing into it with a buddy. You’re about to walk into a dark ICU at 7 p.m., with pager in hand, as “the resident on at night.”

Here’s the situation:

You’re new. You’ve barely learned the unit phone number. And the first time you’ll actually manage multiple crashing patients will be when there’s no one “officially” around except a cross-cover senior and maybe a sleepy fellow who’s covering four different units.

Let’s cut through the nonsense and talk about how you actually survive this curve without burning out or making dangerous mistakes.

1. Before Your First Night: Set the Board in Your Favor

The worst version of this is walking into night one totally cold. Do not do that to yourself if you can help it.

A. Get the lay of the land fast

On your last orientation day—before you disappear into the night schedule—do these things on purpose:

- Ask the day senior: “Tonight, if I’m drowning, who is physically in house I can grab?” Write down names and roles: ICU fellow, in-house intensivist vs home call, rapid response team, code team, respiratory therapist coverage, charge nurse.

- Find where these live: code cart, portable ultrasound, central line carts, art line kits, non-invasive vent machines, suction equipment, extra pumps, backup airway equipment. Walk to each. Physically.

- Ask a bedside nurse (not the attending, not the fellow):

“What do new residents screw up most on nights their first week?”

The answers will be brutally practical. That’s what you want.

B. Build a tiny “ICU nights” cheat kit

You do not need a 40-page binder. You need quick hits you can access in 5 seconds.

On your phone (locked screen notes) or a folded index card:

- Vent basics:

- Common initial ICU vent orders (Mode, FiO2, PEEP, RR, TV by IBW)

- What you do when sats drop: increase FiO2 vs PEEP vs check for disconnection, secretions, tension pneumo, etc.

- Pressor basics:

- Starting doses for norepi, vasopressin, epi

- Target MAP (usually ≥65 unless told otherwise)

- Titration intervals and max dose your unit uses

- Sedation/analgesia go-to’s:

- First-line infusion ranges (propofol, dex, fentanyl)

- Typical bolus rescue doses

- Two or three code meds you always forget:

- Amio dosing (bolus vs drip)

- Adenosine dosing

- Insulin + D50 for hyperkalemia

You won’t remember this stuff at 3 a.m. under stress. Write it down now.

C. Fix your logistics before you’re a zombie

Sleep:

The day before your first night, do a “fake night”:

- Sleep in from morning, stay awake through afternoon.

- Nap 3–7 p.m. if you can. Dark room, earplugs, phone on silent.

- Small caffeine hit right before you leave for your shift—not at 5 p.m.

Food:

Pack actual food. Not just granola bars.

- One real meal (protein + carbs + something that grew in the ground).

- One “middle-of-the-night” snack that won’t wreck your stomach.

- Big water bottle, plus one caffeine source you control (coffee, tea, or an energy drink you’ve used before, not something new).

2. The First Hour of Your Shift: How Not to Get Buried

The first hour sets the tone. You want controlled, deliberate, not-reactive. This is where a lot of new residents screw it up by trying to look “fast” instead of being safe.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Sign in to unit |

| Step 2 | Get sign out from day team |

| Step 3 | Mark sickest patients |

| Step 4 | Brief check of all rooms |

| Step 5 | Clarify any unclear plans |

| Step 6 | Plan tasks and pages |

A. Dominate sign-out (do not just “listen”)

During sign-out from the day resident/senior, your job is to interrogate the list like a prosecutor.

For each patient, you should know:

- Why are they in the ICU? (The one-line “if something goes bad overnight, it will be because of X.”)

- What is their “oh-shit” risk? Are they:

- Stable-ish

- Borderline

- Actively trying to die

- What are the “if-then” plans?

“If MAP < 65 even on norepi 0.1, call fellow before escalating.”

“If sats drop below 88% on current settings, try increasing FiO2 to 80%, suction, ask RT, then call me.”

Ask bluntly:

“Who is most likely to crash tonight?”

Then circle those names.

B. Walk the unit with intention

Do not go sit at a computer for 45 minutes tweaking orders. Do a fast physical walk-through.

For each circled “sickest” patient:

- Stand at the door, scan monitor: HR, BP, SpO2, vent settings, vasopressors.

- Glance at the nurse and say, “Hey, I’m [Name], I’m your night resident. How worried are you about them tonight on a scale of 1–10?”

Nurses will give you the truth. If they say “9,” that’s your first stop. - Ask: “Anything you’re already worried about that isn’t in sign-out?”

Then do a more superficial sweep of the rest. You don’t need to re-exam everyone in the first 30 minutes, but you should at least visually spot check the unit.

3. How to Handle the First Real “Oh Shit” Moment

It always comes earlier than you’re ready. The desat alarm. The MAP of 48. The “room 10 is bradying down.”

Your performance here is not about knowing every answer. It’s about having a process.

A. Your internal script for acute changes

Walk in with three jobs:

- Stabilize what you can quickly. Airway, breathing, circulation.

- Call help early. Not after 20 minutes of flailing.

- Communicate clearly. Short, direct phrases.

A basic internal checklist for a decompensating patient:

- Airway: Is the tube in? Fogging? Capno? Is the patient trying to pull it out?

- Breathing:

- Look at vent: mode, TV, RR, FiO2, PEEP.

- Look at patient: chest rise, wheeze vs no breath sounds on one side, agitation vs obtunded.

- Circulation:

- MAP trend, HR, rhythm, pressors running, access (central vs peripheral).

Say out loud:

“Okay, I’m here. What happened in the last 5 minutes?”

Make the nurse talk. They often have the missing piece.

B. Calling for help does not make you weak; calling late does

If:

- Patient is worsening despite first-pass interventions, or

- You’re about to do something you’ve never done before (starting second pressor, pushing paralytic, major vent change), or

- Your gut is screaming

…you call. Fellow, attending, rapid response. Whoever the ICU culture expects.

Phrase it like this:

“Hey, this is [Name] in the ICU. I have a [age]-year-old here for [reason] who is now [problem]. We’ve done [x, y, z]. MAP is still 50 on norepi 0.2, sats are 86 on 100% FiO2. I need help at the bedside.”

Do not open with, “Um, so, I have this patient who’s kind of…” No rambling. People come faster when you sound serious and competent.

C. After the crisis: force a 60-second learning debrief

Once the patient’s either stabilized or taken to the OR or pronounced, your brain will want to move on. Quick charting, next page, what’s next.

Take 60 seconds with someone more senior (fellow, RT, experienced nurse) and ask one question:

“If I see this same thing again next week, what’s the thing I should do differently or faster?”

That one-question debrief compounds over a month of nights. I’ve seen interns finish an ICU nights block basically practicing at a second-year level because they kept doing this.

4. Managing The List All Night: How Not to Lose the Thread

The second way new ICU night residents drown: death by small tasks, lost pages, and mental fragmentation. Especially right after orientation, when you don’t yet have muscle memory.

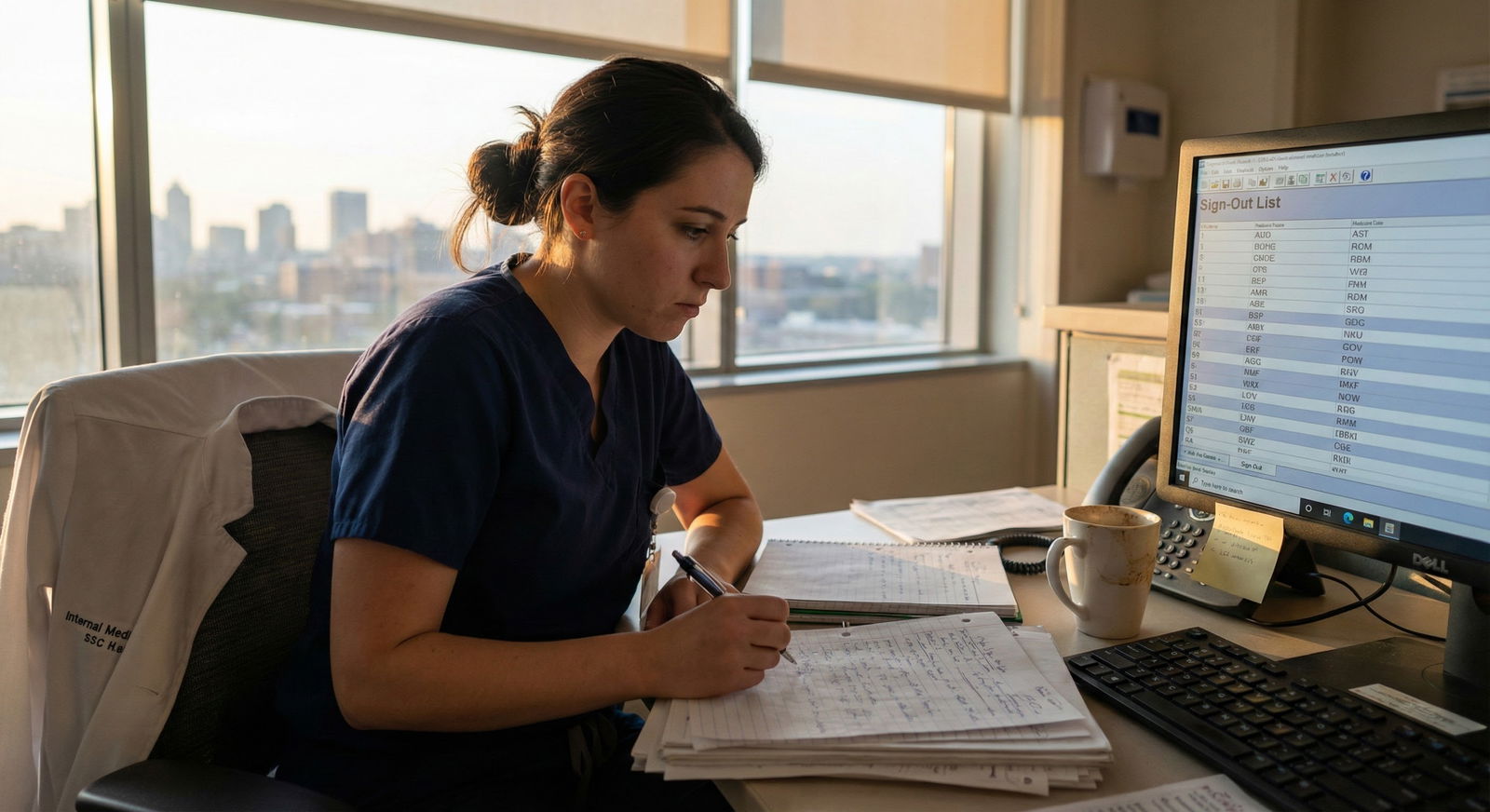

A. Keep a physical “battle list”

Don’t trust the EMR task list alone. You need something right in front of you that your fatigued brain can’t hide behind a window.

Use a folded sheet with columns:

- Room / Name

- “Big picture” (one-line: “Post-op CABG, weaning pressors”)

- What could kill them tonight (bleeding, arrhythmia, sepsis worsening, vent failure)

- To-do overnight (labs, imaging, lines, weaning trials, family update)

- Checkboxes

Every time you get a page, write it down on this list immediately before you stand up. Even just: “Rm 12 – hypotension – recheck BP, consider fluids.”

You’re not too advanced for this. The attendings who seem hyper-organized? They do some version of this in their head or on a card.

B. Prioritizing when everything feels urgent

Here’s a simple prioritization hierarchy when you’ve got three pages at once:

- Actively crashing / vitals acutely bad (MAP <55, sats <88 and falling, suspected stroke, new arrhythmia with instability).

- Time-sensitive but not dying (K 6.5, glucose 30, chest tube not draining but vitals okay).

- Important but can wait 30–60 minutes (family wanting update, med reconciliation questions, routine labs overdue).

Phrase to nurses when you’re triaging:

“I’m in room 10 with a MAP of 40 right now. I see your page about room 5’s NGT issue. Can you keep them NPO and hold meds by tube? I will be there as soon as this is under control.”

Direct. Clear. Respectful. You’re not ignoring them; you’re explaining your triage.

5. Using Nurses and RTs Like the Allies They Are

ICU at night is absolutely not a solo sport. People who try to “play hero” crash hard.

| Situation | First Person to Grab |

|---|---|

| Vent alarms, desats | Respiratory therapist |

| Line issues, pumps, meds | Bedside nurse / charge RN |

| New unstable rhythm | Nurse + call fellow |

| Unsure plan on sick patient | Fellow / in-house intensivist |

| Logistics, bed moves, staffing | Charge nurse |

A. What good nurses and RTs quietly expect from you

They do not expect you to know everything. They do expect:

- That you show up quickly when they say, “I’m worried.”

- That you admit when you don’t know and say, “I’m calling the fellow.”

- That you close the loop. If you say, “I’ll put those orders in,” do it right then or tell them when it’s done.

If a nurse says, “Their pressure looks okay but they just don’t seem right,” pay attention. That sentence has saved more people than any AI sepsis alert.

B. How to ask better questions

Instead of: “What do you think?”

Try: “You know them better than I do—does this change worry you, or does it fit their usual pattern?”

Instead of: “Is everything going okay?”

Try: “If something is going to blow up on this patient tonight, what do you think it will be?”

These are the questions that get you real info, not polite reassurance.

6. Surviving Physically and Mentally: Nights Will Break You If You Let Them

The clinical learning curve is steep. The circadian curve is worse. Coming off orientation straight into nights is like being thrown into cold water.

A. Managing your energy like a finite resource

You have maybe 2–3 “sharp focus” periods in a night and long stretches of semi-functional autopilot.

Rough pattern for a 7 p.m.–7 a.m. shift:

- 7–10 p.m.: Use this “high” for sign-out, sickest patient assessment, knocking out key tasks.

- 11 p.m.–3 a.m.: Protect this window for heavy charting, procedures when possible, family calls that can’t wait.

- 3–6 a.m.: This is danger time. You’re tired, they’re tired. Force checklists, avoid big cognitive decisions alone. If you’re about to make a complex call at 4 a.m., run it by someone.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 19:00 | 8 |

| 21:00 | 9 |

| 23:00 | 7 |

| 01:00 | 5 |

| 03:00 | 3 |

| 05:00 | 4 |

| 07:00 | 6 |

(Scale 1–10. You’ll feel different, but this pattern is real for most people.)

B. Micro-breaks that actually work

You cannot “power through” 12 hours indefinitely. Your brain will quit first.

Concrete tricks:

- Every 2–3 hours, walk one full lap around the unit. Even 3 minutes. Move your legs.

- Build a quick “reset routine” when you feel your brain fogging:

Bathroom, splash cold water, 10 deep slow breaths, half a glass of water, quick stretch. Then sit down and re-open your list. - Use caffeine strategically: early and mid-shift. Not at 5 a.m. unless you don’t care about sleeping post-shift.

7. Handling Impostor Syndrome and Fear of Screwing Up

You’re new. You should feel uncomfortable. The danger is when that discomfort mutates into paralysis or silence.

Let me be blunt: the resident who makes me nervous on ICU nights is not the one asking “too many questions.” It’s the one who never asks for help, never seems confused, and then calls me at 6 a.m. to tell me the patient has been hypotensive since 2.

A. Red flags in your own behavior

Stop if you catch yourself thinking:

- “I don’t want to bother them; they’re probably busy.”

- “I’ll just watch it for a while and see what happens.”

- “I must be stupid for not knowing this already.”

Those thoughts are how small problems turn into crashes.

Replace them with:

- “I’m new and nights are high risk. My bias should be to loop in help slightly early, not late.”

- “If I would feel the need to document this tightly, I should probably discuss it with someone senior.”

B. How to sound competent and ask for help

You don’t need to pretend you’re fine. You do need to present the case coherently when you escalate.

Template:

- “This is [your name], ICU resident.”

- “I’m calling about a [age] [sex] in room X here for [core problem: septic shock, post-op ARDS].”

- “Over the last [time], they’ve [exact change: MAP dropped from 70 to 50 despite norepi uptitration from 0.05 to 0.15].”

- “We’ve already [actions you took].”

- “I’m concerned because [what you think is going on / trend]. I’d like you to [come to bedside / help me decide on X vs Y].”

You sound like you’re thinking. You’re just acknowledging you don’t have the full answer. That’s what you’re supposed to be doing in training.

8. Post-Shift: Protecting Your Future Self

What kills people on their second, third, fourth night is not just fatigue—it’s the accumulated cognitive mess they drag forward.

A. Handoff like someone’s life depends on it—because it does

Morning sign-out back to the day team:

Hit 3 things per sick patient:

- What happened overnight.

- What is different now than at 7 p.m. yesterday.

- What still worries you going forward.

For example:

“Room 12 had recurrent desats around 2 a.m., FiO2 and PEEP escalated, we ruled out pneumo with bedside ultrasound. They’re now on FiO2 80%, PEEP 12, still borderline sats at 90%. I’m worried they’re heading toward needing paralysis and proning soon if this continues.”

Do not sugarcoat to look competent. They need real situational awareness.

B. Debrief your brain before you crash into bed

When you get home, you’ll want to collapse. Discipline yourself to do a 3-minute jot-down:

- 1 thing that went well.

- 1 thing that was shaky that you want to read about (specific: “Shock in cirrhotics” not “Shock”).

- 1 communication move that you liked or hated (either by you or others).

Keep a note stack or app list called “ICU nights lessons.” This is how you turn chaos into learning instead of just losing pieces of yourself.

9. The Emotional Reality: Some Nights Will Just Suck

You’re going to have at least one night where:

- A patient you were just talking to decompensates and dies.

- A family blames you.

- An attending snaps at you in front of everyone.

- You feel like you’re the weak link on the team.

None of that means you shouldn’t be here.

What helps:

- A person. One co-resident, mentor, or friend you can text, “Last night was awful, can I vent for 5 minutes?” Line this up before your block. Don’t wait until you’re already underwater.

- A rule for yourself: no life decisions on post-call days. You’ll want to quit medicine, change specialties, or decide you’re worthless. Those are not real thoughts; they’re sleep-deprived distortions.

- One small ritual to close the night. Walking home without headphones. A specific snack. A shower where you literally imagine the night washing off. Corny? Maybe. It works.

10. If You’re About to Start ICU Nights Right After Orientation: Do This Today

You’re not going to make ICU nights easy. That’s not realistic. What you can do is make them survivable, and maybe even turn them into the steepest learning curve you’ve ever climbed—in a good way.

Here’s your concrete action for today:

Open a note on your phone titled “ICU Nights – Day 0” and add three sections:

- “Who to call” – list your ICU fellow number, in-house attending (if any), charge nurse extension, RT pager/phone. If you do not know these yet, your job today is to ask someone and fill them in.

- “My first 60 minutes script” – bullet what you will do from 7–8 p.m. (sign-out questions, which rooms to see first, the exact sentence you’ll say to each nurse: “I’m [Name], I’m your night resident. What are you most worried about tonight?”).

- “Red flag phrases” – write out 2–3 things you’ll use as triggers to call for help (“MAP < 55 on pressors,” “sats < 88% on FiO2 80 and PEEP 10,” “I feel lost and the nurse is worried”).

Then, before your first night, read that note once. Slowly.

You’re not going to feel ready. Nobody does. But you’ll have a plan, allies, and a process—and in the ICU at night, that’s the difference between just surviving the steep curve and actually climbing it.