Why Buying a Bigger House for the ‘Tax Deduction’ Hurts Physicians

Is your colleague with the 6,000-square-foot McMansion actually “saving on taxes” — or just donating cash to the bank and the government in slow motion?

Let me be blunt: “I bought more house for the write‑off” is one of the most expensive myths physicians fall for. I’ve heard it from attendings, fellows about to sign their first contract, even from a cardiologist who was still paying off six figures of student loans while proudly explaining how his “tax deduction” made the mortgage a “no-brainer.”

He was wrong. And if you’re thinking the same way, you’re about to be, too.

The Core Myth: “The Tax Deduction Makes It Worth It”

Here’s the fantasy:

You: “Yeah, it’s a $2M house and the mortgage is brutal, but the mortgage interest deduction really helps at tax time.”

Reality: The deduction reimburses you for a fraction of what you spend. You’re still bleeding cash; it just hurts less because the IRS gives you a small band‑aid.

Let’s put numbers on it.

Say you’re a married physician couple filing jointly:

Income: $550,000

Marginal federal tax bracket: 35%

State tax: 5% (and SALT already capped at $10k)

You’re looking at a $1.5M house with:

- 20% down ($300,000)

- $1.2M mortgage at 6.5%

- First‑year interest roughly: $78,000

Under current law, you can only deduct interest on up to $750,000 of acquisition debt for a new loan. So most of that interest is not even deductible.

So maybe ~$49,000 of that $78,000 is deductible. At a 35% bracket, that saves you about $17,150 in federal tax.

You did not “save” $17,150. You spent $78,000 of interest to get $17,150 back.

That’s like saying, “I love this store. They give me 22% off if I overpay by hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

If you wouldn’t buy $100 bills for $78, why are you buying $17k of “tax savings” for $78k of interest?

You’re not exploiting the tax code. The tax code is exploiting you.

The Numbers Physicians Actually Live With

Let’s compare a “sensible” physician house versus the “doctor house” upgrade. Same doctor. Same city. Different decisions.

Assume this:

- Sensible house: $800,000

- “Doctor” house: $1,800,000

Same:

- 20% down

- 6.5% interest

- 30‑year fixed

Rough calculations for year 1:

| Category | $800k House | $1.8M House |

|---|---|---|

| Down payment (20%) | $160,000 | $360,000 |

| Mortgage amount | $640,000 | $1,440,000 |

| Yr 1 interest (approx) | $41,000 | $92,000 |

| Property tax (1.25%) | $10,000 | $22,500 |

| Insurance/utilities (est.) | $7,000 | $12,000 |

Only interest on up to $750,000 is deductible for new loans. So:

- On the $800k house, almost all interest on $640k is deductible.

- On the $1.8M house, only interest on the first $750k of $1.44M is deductible. The rest is just…gone.

Now layer in the standard deduction. For 2024:

- Married filing jointly standard deduction: roughly $29,200

So your itemized deductions from housing only help you to the extent they exceed $29k. Many high‑income physicians already hit that with charity + state taxes + some mortgage interest. The incremental effect of “more house” is often marginal.

Let’s translate this into something you feel in your bank account.

The After‑Tax Reality

Assume you already itemize because you have:

- $10,000 SALT (capped)

- $10,000 charitable giving

- Some existing deductions

Add housing:

- $800k house: ~$41k interest + $10k property tax

- $1.8M house: deductible ~$49k interest (on $750k) + $22.5k property tax (but remember SALT cap)

Because SALT is capped at $10k, the extra $12.5k of property tax doesn’t change your deduction. It just drains your bank account.

So your incremental benefit of interest deduction between the two houses is maybe:

- Extra deductible interest: about $8k (49k vs 41k)

- At 35% bracket: $2,800 “tax savings”

You spent:

- Extra interest: ~$51,000

- Extra property tax: ~$12,500

- Extra insurance/utilities: maybe $5,000+

Extra ongoing annual cost: roughly $68,500

Extra tax savings: ~$2,800

So your “smart tax play” is:

Spend an extra ~$68.5k a year to “save” ~$2.8k in tax.

This is not a tax strategy. It’s a lifestyle decision dressed up with accountant‑sounding words.

The Hidden Tax Of Being House Poor

The real damage isn’t just the math on a 1040 form. It’s what that house does to everything else in your financial life.

You do not feel the hit all at once. You feel it five different ways over 10–20 years:

You kill your savings rate.

I’ve seen multiple attendings earning $400–700k whose net worth barely moves for a decade because all their cash goes to mortgage + property taxes + “keeping up” the house.You crowd out real investing.

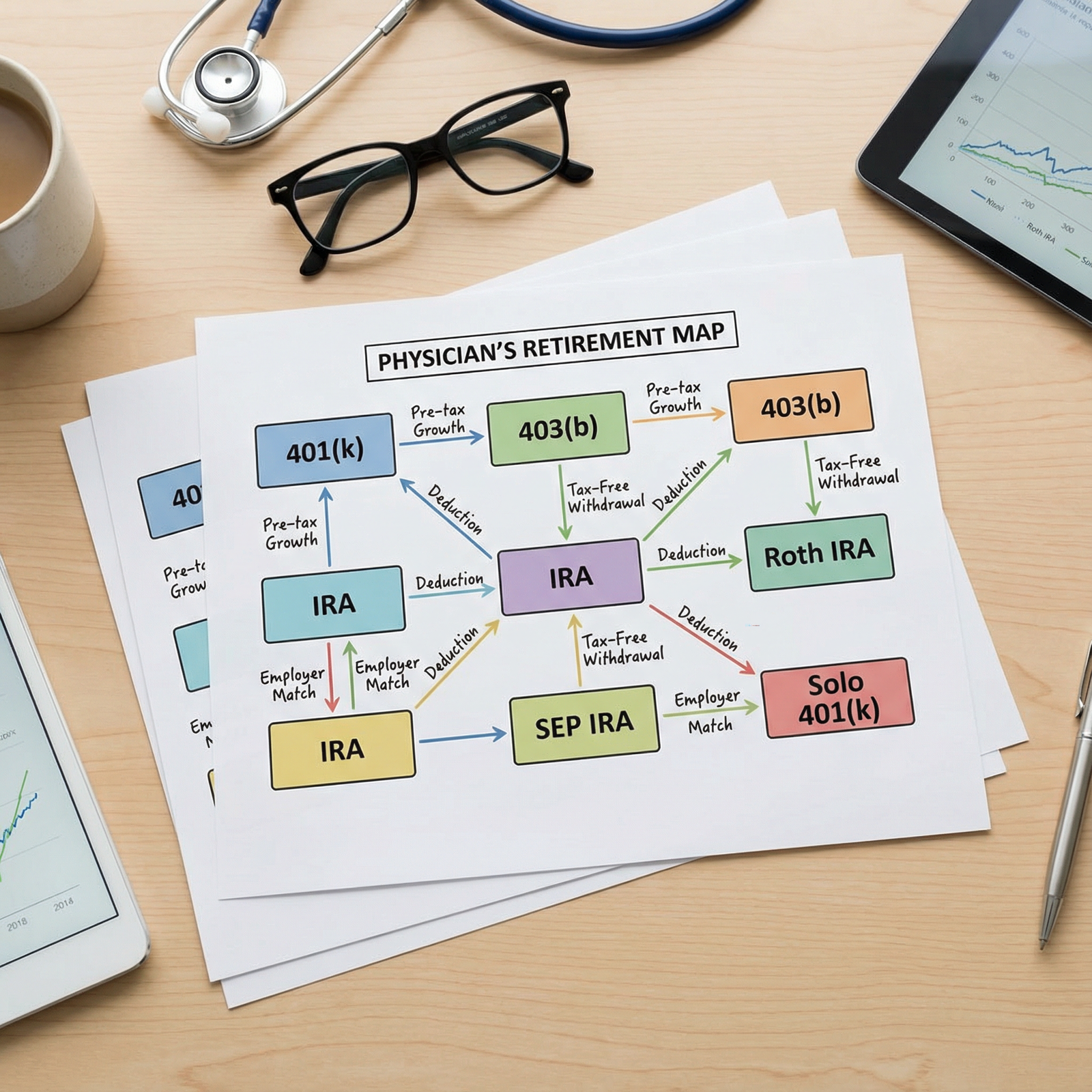

Dollars going to a jumbo mortgage at 6.5% are dollars not going into:- 401(k)/403(b)/457(b)

- Roth backdoor

- HSA

- Taxable brokerage

- Real estate that actually cash flows

The stock market doesn’t care about your granite countertops. Compound interest works on the money you invest, not the house you live in.

You increase career fragility.

Big house = big fixed overhead. That means:- Harder to change jobs

- Harder to cut FTE when you are burned out

- Harder to walk away from a toxic group

I’ve watched hospital admin get away with garbage because physicians literally cannot afford to leave. The mortgage payment is the invisible hand on their throat.

You get stuck on the upgrade treadmill.

Bigger house means:- Higher furnishing costs

- Higher maintenance

- Landscaping, pool, security systems

- “We live in this neighborhood, so of course the kids do travel sports and private school”

All of this feels “normal” around other high‑income families. It’s still lifestyle inflation eating your freedom.

You take on concentrated, illiquid risk.

Your house is:- One asset

- In one local market

- With high transaction costs

- That produces zero income

That’s the opposite of diversification. If housing softens right when you want to downsize or relocate, you’re stuck or you eat a loss.

None of this shows up in the “mortgage interest deduction” line. But it’s the real tax you pay: a tax on your options.

Why The Deduction Sounds Better Than It Is

So why do smart physicians keep falling for this?

1. Confusing “Deduction” With “Credit”

A tax credit reduces your tax bill dollar‑for‑dollar. Spend $1,000 on something, get $1,000 tax credit? That’s powerful.

A deduction merely reduces the amount of income that gets taxed. If you’re in the 35% bracket and you get a $10,000 deduction, you save $3,500 in tax — but you still spent $10,000.

Mortgage interest is a deduction, not a credit. You only get back your marginal rate, not the whole dollar.

2. Forgetting The Standard Deduction

You don’t get a deduction just for having a mortgage. You get a deduction to the extent that your total itemized deductions exceed the standard deduction.

Plenty of younger attendings with modest houses and moderate giving should just take the standard deduction. In that case, your mortgage interest is giving you no extra tax benefit at all.

The bigger house might push you over the threshold — but again, you’re paying tens of thousands more per year for maybe a couple thousand more in tax reduction.

3. Ignoring The $750k Cap

After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the limit for new mortgages is interest on up to $750,000 of acquisition debt (for most married filing jointly cases).

You sign a $1.5M jumbo mortgage?

You’re paying interest on $1.5M.

You’re only getting a deduction on the interest for the first $750k.

The rest is just there to keep the bank profitable.

4. Misunderstanding Marginal Brackets

That “I’m in the 37% bracket” line everyone drops?

Often wrong. And even if it’s technically right, your effective tax rate is almost always lower.

So the mental model of “I save 37 cents on every dollar of mortgage interest” is often fantasy. You’re likely saving at something more like 25–30% effective on the margin once state/federal interplay and phase‑outs are factored in.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 25% bracket | 0.25 |

| 32% bracket | 0.32 |

| 35% bracket | 0.35 |

| 37% bracket | 0.37 |

Each bar is what you “save” in tax per dollar of interest. You’re still out the remaining 63–75 cents.

“But My Home Is An Investment”

No. Your primary residence is a consumption asset that might appreciate.

Could it go up in value? Sure. But here’s the catch:

- That appreciation is on total value, not just equity.

- The leverage cuts both ways.

- Transaction costs (commissions, closing costs, staging) are brutal when you sell.

- Your return is heavily path‑dependent: when you buy and when you sell matters a lot.

Even when it works out, it’s usually not because you “got the deduction.” It’s because you held long enough in a rising market. That’s not a strategy, that’s luck plus patience.

Compare your house to that boring S&P 500 index fund:

- The index spits off dividends.

- You can sell pieces anytime with minimal cost.

- You’re diversified across hundreds of companies.

Your house spits off property tax bills and repair needs.

You need somewhere to live; buying can absolutely make sense. But the “investment” case is often massively overstated, especially once you cross from “comfortable home” to “impressive doctor house.”

Better Ways To Actually Reduce Your Tax Burden

If tax reduction is the goal, there are options that do not require a $10,000 monthly payment and a six‑figure landscaping budget.

Real, physician‑appropriate tax levers:

Max every true pre‑tax account you can.

- 401(k)/403(b), 457(b)

- HSA (if eligible)

- Pre‑tax profit‑sharing if available

- Defined benefit / cash balance plan in some practices

Use the backdoor Roth correctly.

That’s tax‑free growth, not just a deduction.Lean into charitable giving strategically.

Donor‑advised funds, bunching donations into high‑income years, appreciated securities instead of cash — all much more efficient than accidental charity to Wells Fargo.Build a real investment portfolio.

Low‑cost index funds in taxable accounts, maybe targeted real estate that cash flows. These generate income and appreciation without handcuffing your lifestyle.Optimize your business structure (if you’re not W‑2).

S‑Corp salary vs distribution, accountable plans, home office deductions — this is where real tax planning occurs. Not in your kitchen upgrade.

None of this gives you granite countertops. All of it moves you toward financial independence.

When Does a Bigger House Actually Make Sense?

There are legitimate reasons to buy a bigger house. They just have nothing to do with “tax savings.”

It makes sense when:

You can keep total housing costs (PITI) under ~20% of gross income without sweating.

Buying still allows you to:

- Max retirement accounts

- Pay off student loans on a sane timeline

- Invest extra in a taxable account

- Maintain a 3–6 month emergency fund

You could live there at least 7–10 years.

You’re not depending on appreciation to “bail you out.”

You could tolerate a pay cut or job change without panicking about the mortgage.

If those are true and you want the house? Fine. That’s lifestyle. Own that openly.

Just stop lying to yourself (or letting your realtor/loan officer lie to you) that this is a tax strategy. It is not.

Quick Reality Check Before You Sign

Before you “stretch a bit” because “we’re in a high bracket and the deduction will help,” run this simple test:

Ask your lender for an amortization schedule.

Look at year 1 interest on the loan.

Multiply that number by your marginal tax rate (not effective — marginal).

That’s your rough tax savings from the interest.

Compare that to:

- Extra annual housing cost vs a smaller, perfectly adequate home

- Lost investing potential of the extra cash outflow

- Lost flexibility in your career

If the trade feels stupid when you see the numbers in dollars instead of vibes, it is stupid. Walk away.

If you still want the house knowing full well it’s a lifestyle splurge? That’s fine. Just call it what it is.

The Bottom Line

- Mortgage interest deductions do not make expensive houses financially smart; they just slightly soften an otherwise bad deal.

- Bigger houses quietly suffocate physician wealth and flexibility by crushing cash flow and crowding out real investments.

- If you want a big house, buy it as a lifestyle choice — but stop pretending the IRS is “helping you” do it. It isn’t.