Programs do not blindly trust the research you list. They verify it far more than most applicants realize.

Let me walk you through exactly how.

Residency programs use a mix of common-sense checks, quiet background verification, and direct questioning to figure out whether your research is real, accurate, and honestly represented. And if they catch you stretching the truth? It follows you. Across programs. Across years.

You’re not just listing “stuff you did.” You’re submitting a document that a faculty member could pick up and say: “This is my field. I know these people. Let’s see if this holds up.”

Here’s how they check—and what that means for how you should list your research.

1. The Basic Reality Check: Internal Consistency

First level: programs ask, “Does this even make sense?”

They look for:

- Does your timeline line up with school years, leaves of absence, and other activities?

- Are your roles plausible for your training level?

- Does the volume of research look humanly possible?

Example I’ve seen:

MS3 lists “12 first-author publications” over 18 months, all in high‑impact journals, while also full-time in clerkships and with no research year. Any faculty who has ever published will raise an eyebrow. That doesn’t mean impossible. But it does mean they’ll dig deeper.

They also scan for:

- Repeated “submitted” or “in preparation” entries with no final outcomes.

- “Ongoing” projects from two or three years ago that never progressed.

- Titles that sound like inflated versions of a small QI or case series.

If something smells off at this stage, many programs will quietly flag your file. You might still get invited. But you’ll be tested in the interview.

2. Direct Verification with Your PI or Mentor

This is the most straightforward—and it happens more often than applicants think.

Programs will:

- Email or call your listed research mentor.

- Ask other faculty in the same department, especially if they know each other.

- Cross-reference within their own institution if you did research there.

Typical email from a PD to a mentor (I’ve seen versions of these):

“We’re interviewing Dr. X who listed you as mentor for several oncology projects. Can you comment on their role and performance on your team?”

That’s it. Short and lethal.

If you claimed “designed the study, performed all data analysis, and drafted the manuscript,” and your mentor tells them, “They helped with data collection; analysis was done by our statistician and drafting by a fellow,” your credibility just crashed.

Programs pay attention to:

- Whether your described role matches your mentor’s description.

- Whether the number and status of projects sound reasonable.

- Whether you were honest about your actual contribution.

You don’t always know when this is happening. There’s no warning. And there’s no appeal.

3. Publication and Abstract Cross-Checking

If you list anything as “published,” “accepted,” or “in press,” programs can and do look it up.

They’ll search:

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Journal websites

- Conference programs (e.g., ATS, ASCO, AHA, RSNA)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| PubMed | 90 |

| Conference Programs | 70 |

| Google Scholar | 60 |

| Mentor Contact | 80 |

| Internal Faculty Knowledge | 50 |

If they can’t find it:

- Sometimes it’s just a mismatch in the title or journal name.

- Sometimes the journal or conference isn’t indexed.

- Sometimes your “accepted” paper…wasn’t.

What irritates faculty the most:

- Listing something as “published” when it’s actually just “submitted.”

- Giving the wrong journal (upgrading from a low-tier journal to a big-name one on the application).

- Making up volume/issue/page numbers.

If they suspect you’re embellishing, they’ll bring it up:

“Tell me about this paper in JAMA you listed as accepted—what was the review process like? When is it expected to appear online?”

If you flail on basic details, they’ll go from curious to suspicious very quickly.

4. Interview Questions Aimed at Exposing Exaggeration

The interview is where most “verification” happens—subtly.

Faculty will:

- Pick one or two of your projects at random.

- Ask you to explain them in plain language.

- Drill down just enough to see if you actually did what you claim.

Typical questions:

- “What was the main question your study was trying to answer?”

- “How did you decide which statistical tests to use?”

- “If I gave you the raw data again, could you walk me through your analysis plan?”

- “What did you personally do on this project that wouldn’t have happened without you?”

They are not always looking for a specific technical answer. They’re watching for:

- Comfort level with the material.

- Whether your description of your role is consistent across different ways of asking.

- Whether you admit limits: “Our statistician chose the test; I helped interpret results.”

The fastest way to get labeled as dishonest: giving vague, buzzword-heavy answers that dodge specifics.

Example of a bad answer:

“I was heavily involved in the study design and data analysis, and we used advanced statistical methods to compare outcomes between groups.”

Okay, which methods? What groups? What outcome?

If you can’t answer simple follow-ups, they assume the line on your application is inflated.

5. Silent Red Flags That Programs Notice

Programs rarely email you to say, “We don’t believe your research.” They just do three things:

- Don’t invite you.

- Don’t rank you.

- Tell their colleagues at other programs.

Here’s what sets off quiet alarms:

- A long list of “in preparation” projects with no completed work.

- Multiple first-author “publications” for which you can’t provide citations.

- Mislabeling a poster as an “oral presentation” when it clearly wasn’t.

- Listing case reports as “clinical trials” or “prospective cohort studies.”

- Fancy-sounding project titles that don’t match your training level.

| Inflated Entry | Better Honest Version |

|---|---|

| Designed and led multicenter RCT | Assisted with patient recruitment for multicenter RCT |

| Performed all statistical analysis | Collected data; analysis done by biostatistician |

| Senior author on review article | Contributed sections to mentor-led review article |

| Lead investigator on QI project | Participated in team-based QI project |

You don’t have to undersell yourself. But if your description reads like a grant application written by a full professor and you’re an MS3? They’re not buying it.

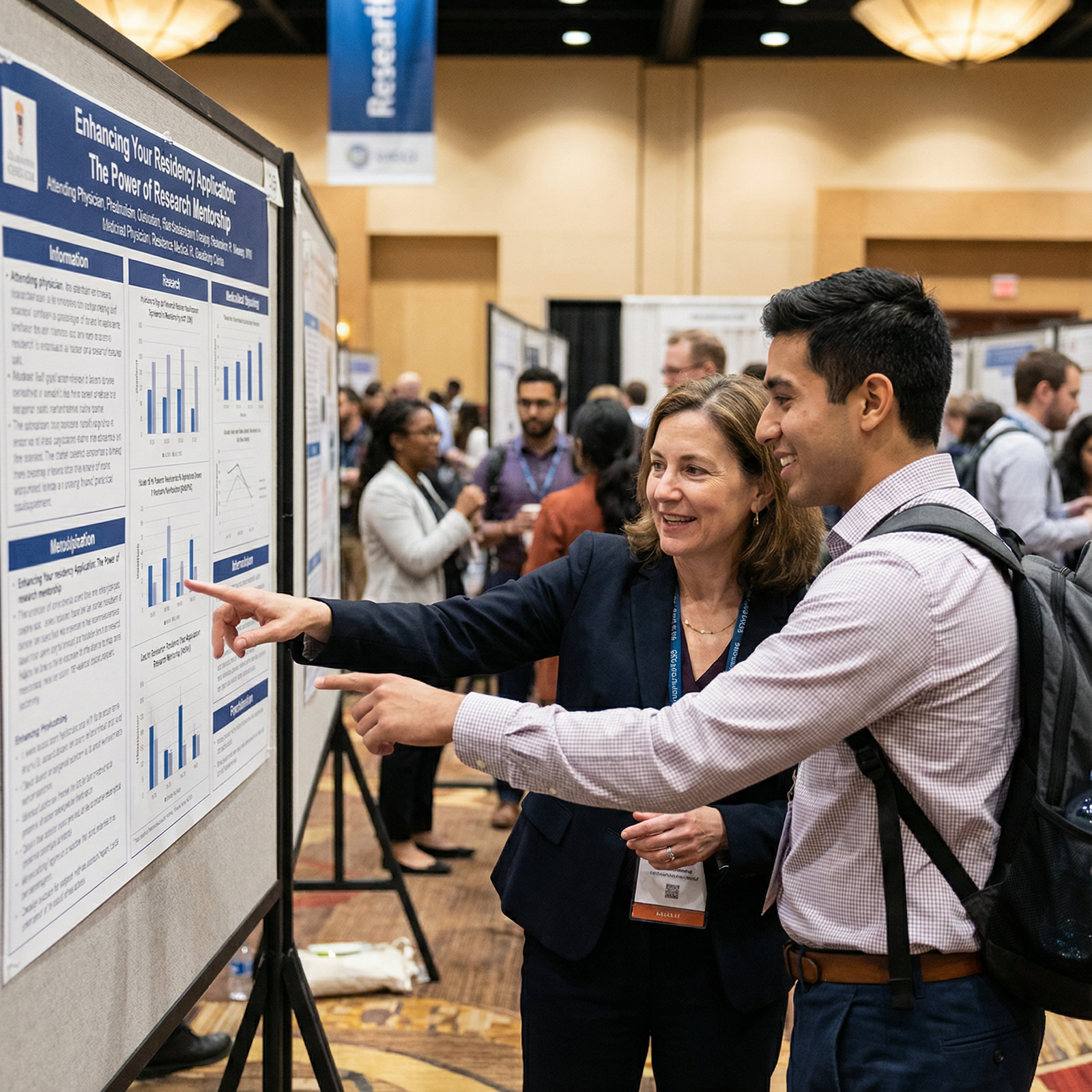

6. Internal Faculty and “Small World” Verification

Medicine is a small world. Academic medicine is microscopic.

Programs use:

- Their own faculty who know your school, your mentors, or your subspecialty.

- Informal conversations at conferences, over email, or even text.

I’ve heard variations of this hundreds of times:

“Hey, we’re interviewing a student from your place—X. They say they worked closely with Dr. Y on three cardiology projects. Solid?”

And then the reply:

- “Yes, strong student, did good work.” → Huge plus for you.

- “Name doesn’t ring a bell.” → Neutral at best.

- “They helped minimally; surprised they listed that much.” → That’s a problem.

Again, you’ll never hear about this directly. But it absolutely affects how much they trust everything else on your application.

7. How Far Do Programs Go for Different Types of Research?

Not all research is treated equally. Programs calibrate their skepticism.

Here’s a rough pattern:

Big, impressive claims (e.g., RCTs, first-author high-impact papers, multicenter trials)

→ High chance of verification and probing.Modest, believable roles (chart review, QI projects, small case series)

→ Quick plausibility check; fewer deep dives.Activities clearly labeled as “student research experience,” “summer project,” or “short-term scholarly activity”

→ They look more at what you learned than whether it changed the field.

, Basic case reports](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_svg/chart-likelihood-of-deep-verification-by-research-type-9176.svg)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| High-impact publication claims | 90 |

| Multicenter trials | 85 |

| Standard retrospective studies | 60 |

| [Single QI projects](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/research-residency-applications/can-quality-improvement-and-audits-count-as-research-for-eras) | 40 |

| Basic case reports | 30 |

So if you stack your application with overinflated, heroic-sounding roles, you’re inviting scrutiny. If you describe realistic contributions carefully and honestly, most programs will accept them at face value and use interviews just to see if you can talk about them coherently.

8. How to List Research So You Never Worry About Verification

Here’s the part you actually control.

You want your research section to be:

- Verifiable

- Consistent

- Defensible under questioning

- Honest without being self-sabotaging

Concrete rules:

Titles and authorship

Use the real title from the abstract/manuscript as it is or will appear.

Spell authors accurately and in correct order. Don’t insert yourself where you’re not listed.Status labels

Be conservative and accurate:- “Published” only if it’s actually published (online or in print).

- “Accepted” only with formal acceptance (not “positive reviewer comments”).

- “Submitted” only if the manuscript is fully submitted to a specific journal.

- “In preparation” sparingly; list only real, active projects.

Roles and descriptions

Use 1–2 lines to say what you actually did. Examples:- “Collected and entered clinical data; assisted in drafting methods section.”

- “Performed chart review and basic descriptive statistics under supervision.”

- “Designed survey, managed REDCap database, prepared abstract for submission.”

Don’t upgrade your role

If you were a helper, say you were a helper. Your honesty is more impressive than a fake big title.Be ready to talk about anything you list

If you cannot clearly explain the project’s goal, methods, and your role in 2–3 sentences, either:- Learn it well before interview season, or

- Don’t list it.

9. What Happens If Programs Catch Dishonesty?

This part isn’t subtle.

If a program concludes you lied or significantly exaggerated:

- They can drop you from their rank list immediately.

- They can notify your dean’s office or academic affairs.

- They can mention the issue to colleagues at other programs.

And yes, that can be career-limiting.

I’ve seen:

- An applicant caught fabricating an “accepted” article. Journals had no record. Their home institution got a call. That student scrambled to explain themselves to both sides.

- Another who listed imaginary roles in a grant. The PI denied it. That applicant didn’t match in that specialty.

You might think, “But what if nobody checks?” Wrong mindset. Enough people check that the risk-to-reward ratio on lying is terrible.

10. Practical Strategy: Audit Your Research Section Before Submitting

Before you hit “submit” on ERAS, do a ruthless self-audit.

Ask yourself:

- Could my mentor read this and say, “Yes, that’s accurate” without hesitation?

- Could I be quizzed on any line by a specialist in that field and sound competent?

- Could someone find my “published/accepted” work with a reasonable search?

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start Research Review |

| Step 2 | Fix details |

| Step 3 | Downgrade status |

| Step 4 | Clarify actual contribution |

| Step 5 | Review project or remove |

| Step 6 | Keep entry |

| Step 7 | Is title and journal accurate? |

| Step 8 | Status honest? |

| Step 9 | Role clearly described? |

| Step 10 | Can you explain project? |

If an entry fails any step and you aren’t willing to fix it, delete it. A shorter, fully honest research section beats a bloated, questionable one every time.

11. What Programs Actually Care About in Your Research

Remember: they’re not hiring you as a full-time researcher on day one. They’re asking:

- Can you follow through on scholarly work?

- Are you intellectually curious?

- Do you understand basic study design and evidence?

- Are you honest and self-aware about your role?

A simple, clearly described retrospective chart review where you:

- Collected data,

- Helped formulate a question,

- Learned basic stats,

and can discuss it thoughtfully in an interview can do more for you than a sketchy list of six “in press” RCTs that no one can find.

12. Bottom Line: How Programs Verify Your Research

To answer the headline question cleanly:

Programs verify the research on your application by:

- Checking for internal consistency and plausibility.

- Contacting your mentors or PIs directly.

- Looking up your publications, abstracts, and presentations.

- Using faculty connections and informal networks.

- Probing your understanding during interviews.

They don’t fact-check every line for every applicant. But they check enough—and especially where claims are big, unusual, or critical to your story.

So build your research section on one rule: anything you list should survive both a PubMed search and a blunt phone call to your mentor.

FAQ: Research Verification in Residency Applications

1. Do programs actually contact research mentors, or is that rare?

They do contact mentors—especially for top candidates, unusual research claims, or key home-institution projects. It’s not universal for every single applicant, but it’s common enough that you should assume anything tied to a specific mentor could be checked.

2. Can I list a paper as “accepted” if we’ve only received positive reviewer comments?

No. “Accepted” means you have a formal acceptance decision from the journal. Anything short of that is either “revised and resubmitted” (if you’re being scrupulously precise) or still “submitted.” If a program contacts the journal or your PI and finds no acceptance, you look dishonest.

3. Is it okay to include projects that never led to a publication?

Yes. Many residents match with mostly unpublished research. Just label them accurately as “project,” “abstract,” or “ongoing study,” and describe your role and what stage the work reached (e.g., “data collection completed; manuscript not submitted”).

4. What if my name isn’t on the abstract yet, but I contributed?

If your name is not listed anywhere on the abstract or presentation, you must be very careful. You can mention it as “research experience” in a description (e.g., “assisted with data collection on Dr. X’s project presented at Y”), but do not present yourself as an author or presenter if you weren’t.

5. How bad is it if I slightly exaggerate my role—like saying I ‘analyzed data’ when I mostly helped input it?

It’s worse than you think. Once faculty sense that you inflated one role, they question everything else you wrote. And under interview questioning, that small exaggeration is extremely easy to expose. Say what you really did. “Entered data into REDCap and reviewed preliminary results with the team” is perfectly respectable—and infinitely safer.