Managing two crashing patients at once is not a “rare nightmare scenario.” It is your future Tuesday night on call. If you do not have a system, you will default to panic and guesswork. That is how bad outcomes and M&M stories are born.

You need a playbook. Not vibes. Not “I’ll just stay calm.” A concrete, repeatable way to prioritize when everything is on fire at the same time.

This is that playbook.

The Core Rule: Physiology Beats Everything Else

When emergencies hit simultaneously, residents often prioritize by:

- Which nurse sounds more upset

- Which patient they “know better”

- Which problem they feel more confident managing

All three are wrong.

You must prioritize by one thing only:

Immediate threat to life or irreversible harm, based on current physiology.

Not diagnosis. Not age. Not how long they have been waiting. Current physiology.

Think in this order:

- Airway

- Breathing

- Circulation

- Neurologic catastrophe (stroke, seizure, unresponsive)

- Time-sensitive but not immediately crashing (STEMI, sepsis without shock, etc.)

- Everything else

When you are juggling multiple emergencies, this turns into a constant loop:

- Who is at risk of dying in the next 5 minutes?

- Who is at risk of dying in the next 30 minutes?

- Who is at risk of deteriorating in the next 1–2 hours?

You handle them in that order. Every time.

Step Zero: A Standardized “Incoming Emergency” Script

Your real bottleneck is not just time; it is information. Most residents get incomplete, emotional, or disorganized reports from the floor.

You fix that by forcing structure.

When you get any “urgent/emergent” call, you go into script mode. You control the call.

You say, calmly and firmly:

“Okay, I am with you. Give me a focused report:

- Patient name and location,

- Why you are calling right now,

- Latest vitals and mental status,

- What has already been done.”

Then you shut up and let them answer. If they wander, you pull them back:

“Stop. Just answer number 2. Why are you calling right now?”

You are filtering for immediacy and severity.

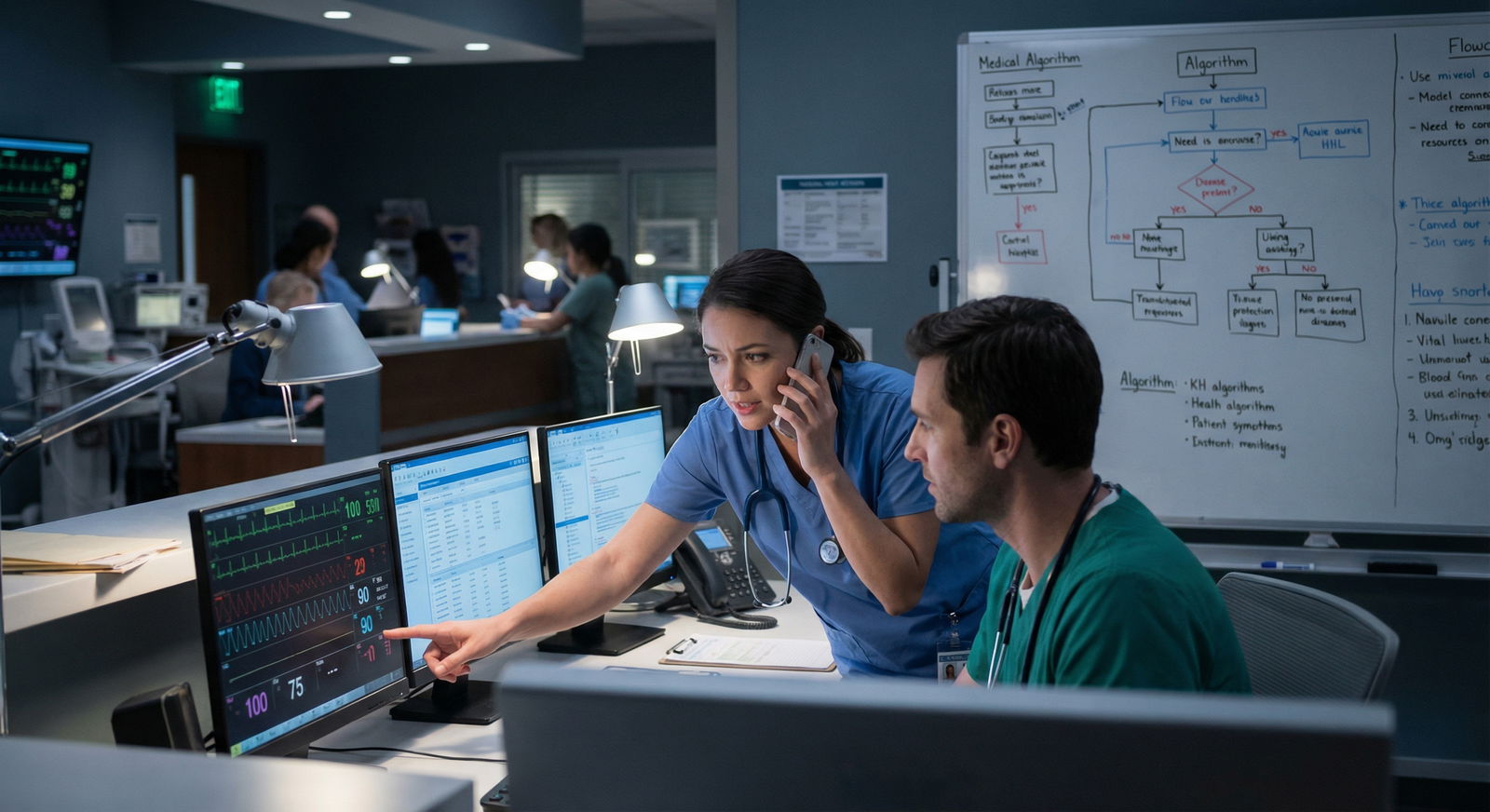

The Three-Call Chaos: How to Triage in Real Time

Picture this. You are on night float. Three calls hit in 90 seconds:

- “Room 814 is desatting to 78% on 6 L nasal cannula.”

- “Room 622 just had chest pain, EKG pending.”

- “Room 930 is hypotensive, 70/40, on antibiotics for pneumonia.”

You feel that surge of adrenaline. This is where people freeze or pick randomly.

Instead, you run the Rapid Triage Grid in your head.

| Case | Problem Type | Risk of Death in 5–10 min | First Action Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| 814 | Hypoxia | Very high | 1 |

| 622 | Chest pain (stable) | Medium, depends on EKG | 3 |

| 930 | Hypotension/shock | High | 2 |

Priority order is clear:

- Hypoxia (814)

- Shock (930)

- Chest pain without clear instability (622)

Now let’s turn this from concept to steps.

Step 1: Get Micro-Data From Each Call – Fast

You need a 10–15 second data burst from each nurse. This is where you earn your salary.

For any emergency call, you quickly ask:

- Vitals – “What are the last vitals? Especially BP, HR, RR, O2 sat.”

- Mental status – “Awake and talking? Confused? Unresponsive?”

- Trajectory – “Is this a sudden change or gradual?”

- Interventions – “What is running now? Any oxygen, fluids, pressors, code meds?”

That is it. No digging through the chart on the phone. That comes later.

Example replies:

- Room 814: “Sat 78% on 6 L, RR 30, BP 140/80, patient is awake but struggling to breathe. This is new.”

- Room 930: “BP now 70/40, HR 120, sat 94% on 2 L, patient more lethargic, got first liter of fluids half an hour ago.”

- Room 622: “BP 135/80, HR 95, sat 98% on RA, chest pain 7/10, EKG being done now.”

From this, you can rank threat level.

Step 2: Decide Where Your Body Goes First

You cannot be in three places at once. Stop trying.

You make a conscious decision where your physical presence is needed first. And you communicate it. Out loud. To the nurse.

In the above scenario:

- You go physically to Room 814 (severe hypoxia).

- You give clear, specific phone orders for Room 930 while walking.

- You tell 622 to finish the EKG and page you the second it is done – no interruptions before that unless hemodynamics change.

You say:

- To 814: “I am coming there now. Put the patient on non-rebreather 15 L. Apply continuous pulse ox and get a STAT set of vitals.”

- To 930: “Start another 500 mL bolus now, hang it wide open. Put the patient flat. Get a full set of vitals and call the rapid response team now. I will come there next.”

- To 622: “Get a STAT EKG and troponin. Page me again only if vitals drop or EKG is back.”

You just created order out of chaos. You are not “ignoring” anyone. You are sequencing.

Step 3: Use Teams and Systems – You Are Not Alone

If you try to personally micromanage three crashes, you will fail two of them.

You need to learn to activate systems early:

- Rapid response / MET team

- Code team

- Anesthesia / ICU backup

- Senior resident / fellow

- Charge nurse

Stop thinking of yourself as the only line of defense. You are command, not a one-person pit crew.

When to pull the rapid response / code trigger

If any of the following are true and you have more than one active issue:

- Sustained O2 saturation < 90% despite increased oxygen

- SBP < 90 or MAP < 65 with signs of poor perfusion

- New unresponsiveness or seizure

- Concern for impending intubation or crash

You do not “wait to see.” You say to the nurse:

“Call a rapid response in 930 now. Tell them I am on my way after I stabilize another patient.”

That line does two things:

- It reassures the nurse you are actively managing.

- It mobilizes more hands without you needing to be there to start.

A Simple On-Call Prioritization Algorithm

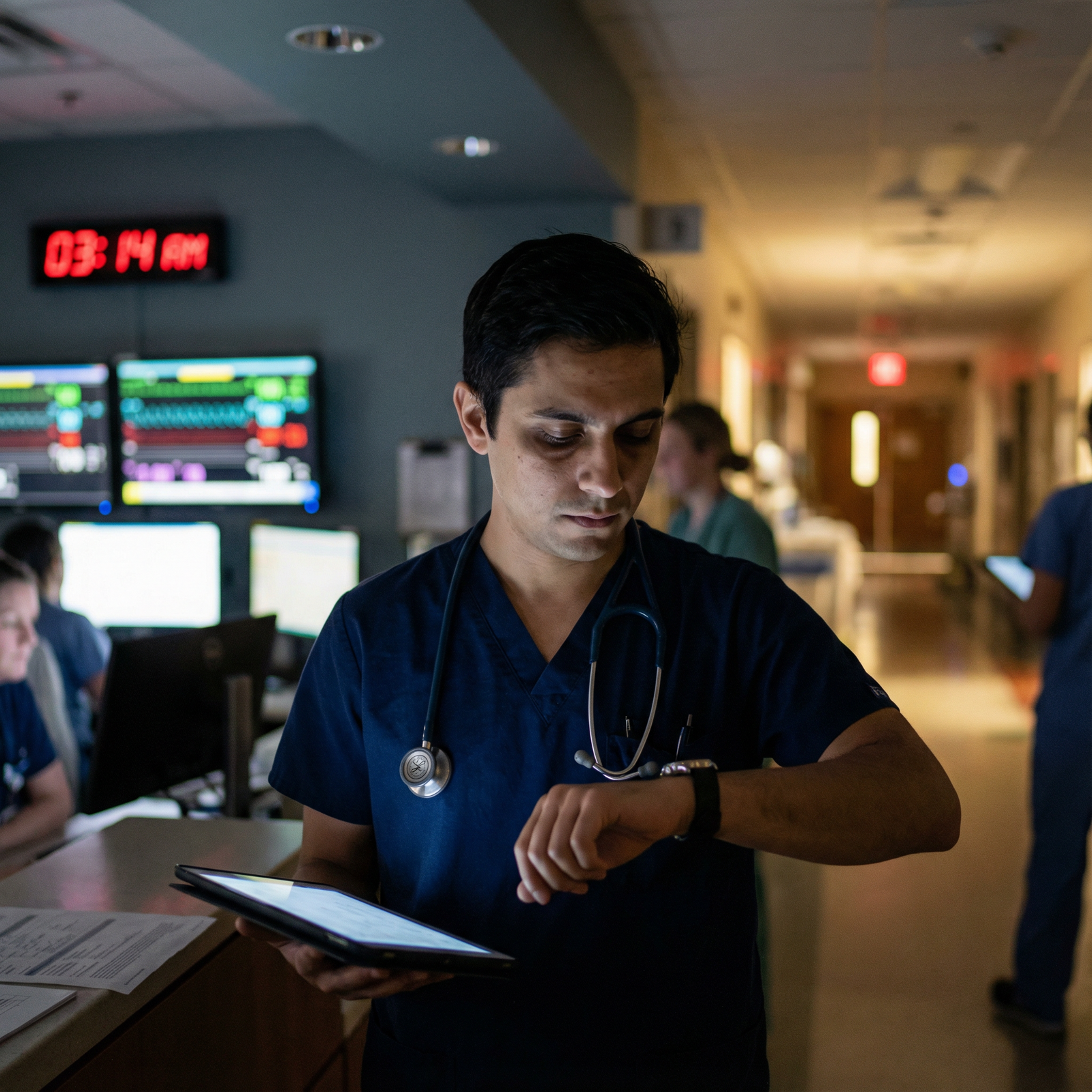

You need something you can mentally run at 2 a.m. when your glucose is 40 and your brain is fried.

Here is the On-Call Prioritization Algorithm you can memorize:

Answer the page. Get the 4 key data points:

- What triggered the call right now?

- Vitals

- Mental status

- Interventions already done

Classify the call into one of four buckets:

- Red: Threat to life in minutes (airway, severe hypoxia, shock, unresponsive, seizure, anaphylaxis, pulseless rhythm)

- Orange: Threat to organ or life in hours (STEMI with stable vitals, new sepsis, GI bleed but stable, bad arrhythmia with stable BP)

- Yellow: Significant change but not crashing (worsening pain, rising creatinine, new fever, soft but not shocky BP)

- Green: Routine issue or minor change (PRN meds, borderline labs, non-urgent questions)

If you get multiple calls at once:

- Handle Red > Orange > Yellow > Green

- Within the same color, prioritize by:

- Who is currently alone vs already with multiple nurses / RRT?

- Who needs your specific skill vs can be stabilized by protocol?

Decide:

- Where your body goes first

- Where your orders go first

- Where a team should be activated

Reassess every 10–15 minutes:

- Has any Yellow become Orange?

- Has any Orange become Red?

- Does anyone need ICU-level care now?

To help you visualize this, think of your night like a flowchart, not random scatter.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Emergency Page |

| Step 2 | Get 4 Key Data Points |

| Step 3 | Go in person now |

| Step 4 | Give phone orders and plan |

| Step 5 | Schedule in-person eval |

| Step 6 | Green - Handle when free |

| Step 7 | Rank by Red > Orange > Yellow |

| Step 8 | Continue Care and Reassess |

| Step 9 | Red - Immediate Threat? |

| Step 10 | Orange - Hours Threat? |

| Step 11 | Yellow - Significant Change? |

| Step 12 | More Emergencies? |

How to Talk So Nurses Trust Your Prioritization

If you do not communicate your reasoning, it will look like you “do not care” about the patient you are not seeing first.

You fix this with one or two clear sentences.

When you cannot come immediately, say:

“I hear you. This is important. Right now I am at a bedside for a patient with immediately life-threatening hypoxia. You are next. Here is what I want you to do while I get there…”

Then give specific tasks, not vague reassurance:

- “Recheck vitals in 5 minutes and write them down.”

- “Draw a lactate and basic labs now.”

- “Start NS at 100 mL/hr while we gather more data.”

- “Put the patient on the monitor and call me back if BP < 90 or HR > 130.”

This does two things:

- Buys time safely.

- Shows you are actively managing, not just deferring.

Pre-Shift Preparation: Reduce Cognitive Load Before the Chaos

If you walk into night float blind, every emergency becomes harder. You can front-load some of the work.

Before the pager starts screaming:

Scan the list and pre-identify “fragile” patients:

- On high-flow O2 or BiPAP

- Borderline BPs on pressors or multiple boluses

- Active GI bleed, large PE, severe sepsis

- Complex post-ops, especially POD 0–1

Make a quick note (mental or written):

- “Room 708 – borderline, likely to desat.”

- “Room 911 – sepsis, might need more fluids or step-up to ICU.”

If possible, see the most fragile patient early in your shift when you are fresh.

- You can adjust orders proactively: more frequent vitals, step closer to ICU monitoring, discuss expectations with nurse.

This way, when the call comes, you are not starting from zero.

Delegation and Parallel Processing: Multiply Your Presence

Even as a junior, you are allowed to say:

“I need help.”

Effective residents know when and how to do that.

Examples of smart delegation

To the charge nurse:

“I have two unstable patients. Can you assign an extra nurse or float to 930 for the next 30 minutes? They are hypotensive and getting fluids.”To another resident / intern (if available):

“I am tied up in a respiratory failure situation. Can you go eyeball 622, review the EKG when it comes up, and call me with a summary?”To the rapid response team:

“I am currently managing a different crashing patient. Please start your standard hypotension protocol, and I will join as soon as I can.”

You are not dumping. You are coordinating.

Mental Bandwidth: Limiting Your Active “Task Slots”

On call, you only have room in your working memory for about 3–4 active “threads” before things start dropping.

So you do not store everything in your head. You externalize.

Create a quick and dirty “hot list” for the next 60–90 minutes:

- 814 – hypoxic episode, now on NRB, ABG pending

- 930 – septic shock, 2nd liter running, RRT at bedside

- 622 – chest pain, EKG pending

- 704 – stable but new fever, orders placed

Update this list every hour or after each big event. Cross out resolved issues.

This sounds trivial. It is not. I have watched good residents crash cognitively because they were trying to “remember all the things” instead of writing them down.

Using Scoring Systems Without Becoming a Robot

Yes, early warning scores, sepsis bundles, etc., exist. They help you sort borderline or unclear cases when you are tired.

But do not let them override what is right in front of you.

Example:

- Patient A: qSOFA 2, but sitting up, joking, great urine output.

- Patient B: qSOFA 1, but looks gray, sweating, and confused.

You see both numbers. You trust your eyes more than the score.

Scoring systems can help you:

- Justify ICU transfer when bed control is being difficult

- Recognize when a “sort of sick” patient is escalating

- Standardize responses with nurses and RRT

But in simultaneous emergencies, physiology and appearance still rule.

After the Storm: Mini-Debriefs and Damage Control

Once the acute phase is over—even 5–10 minutes of breathing room—you do two things.

Quick scan for fallout:

- Any labs you ordered but did not review?

- Any EKG that is sitting in the system untouched?

- Any family that needs updating immediately because things changed drastically?

Micro debrief with nurses (30–60 seconds):

- “Thanks for jumping on that so fast. For next time, if you see sats drop like that, go straight to NRB and page me STAT.”

- Or, “If we get another shock situation, call rapid response early like you did. That was exactly right.”

You are quietly training the unit to align with your playbook. Future emergencies will be smoother because you invested 60 seconds here.

Example Night: Walking Through a Realistic Sequence

Let me walk you through a compressed real scenario I have seen almost exactly as described.

2205 – Call 1: “Room 512 is not waking up well, hard to arouse, was fine an hour ago.”

You get vitals: BP 150/90, HR 88, sat 96% RA, RR 10, on opioids PCA.

Bucket: Orange/Red borderline (possible opioid overdose, neuro issue). You tell them:

“Stop the PCA, apply oxygen 2 L, get a glucose check now. I am coming there after I handle another call.”

2207 – Call 2: “Room 420 is 60/30, on pressors in the step-down.”

Vitals: HR 130, sat 92% on 4 L, mentation worsening, on norepinephrine already.

Bucket: Red. Threat in minutes. You physically go to 420 first, tell nurse:

- “Call rapid response now. Get another set of vitals. Check line sites, check for arrhythmia.”

While brisk-walking, you call back 512 nurse again:

“Update?” Glucose 45. You say:

“Give 25 grams IV dextrose now. I will be there as soon as I stabilize a shock patient.”

In 420, you:

- Confirm BP manually if suspicious.

- Check rhythm on monitor.

- Bolus 500 mL fluid if not overloaded.

- Adjust pressor, consider adding second agent.

- Call ICU to transfer.

Once 420 is somewhat stabilized or ICU is at bedside, you peel away to 512, now post-dextrose, more awake. You assess need for naloxone, adjust opioids, maybe order ABG or CT head if not improving.

Notice what you did not do:

- You did not run to the sleepy patient first because “unresponsive” sounds scary.

- You did not stay glued to 420 for an hour while 512 stayed hypoglycemic and under-monitored.

You handled both in priority sequence, using the team and clear phone orders.

Build Your Own Pocket Playbook

Do not just “like” this mentally and move on. That is useless on a 3 a.m. call.

Take 15 minutes and build:

A one-page note (physical or digital) with:

- Your bucket definitions (Red / Orange / Yellow / Green)

- Your standard phone script for new emergencies

- Default initial orders for:

- Hypoxia

- Hypotension / sepsis

- Chest pain

- Altered mental status

Save it in your white coat, notes app, or on your workstation.

For the next three call shifts, force yourself to actually use the script:

- Classify each emergency into a bucket

- Decide explicitly where your body goes first, and where your orders go first

Over time, you will not need the paper. The logic will be muscle memory.

Your Next Step Today

Open a blank note on your phone or pull out a piece of paper. Write four headings:

- RED – minutes

- ORANGE – hours

- YELLOW – change

- GREEN – routine

Under each, list 3–5 example problems (hypoxia, shock, STEMI, new fever, etc.) as you would see them on your service. Then draft the exact sentence you will use the next time two emergencies hit at once:

“I am coming to [room] first because [reason]. For your patient, here is what I want you to do right now while I am on my way…”

That one sentence, ready in your back pocket, will make your next chaotic call night safer for your patients and saner for you.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Red - Immediate | 10 |

| Orange - Hours Threat | 20 |

| Yellow - Significant Change | 30 |

| Green - Routine | 40 |

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Early Night - 19 | 00 |

| Early Night - 20 | 00 |

| Peak Chaos - 22 | 00 |

| Peak Chaos - 23 | 00 |

| Late Night - 01 | 00 |

| Late Night - 03 | 00 |

| Late Night - 05 | 00 |