The dogma that “you should max every retirement account, every year” is lazy advice for physicians. Sometimes it is flat‑out wrong.

For high‑income docs, blindly stuffing money into every pre‑tax vehicle can increase lifetime taxes, trap money where you cannot use it, and destroy flexibility right when you need it. The math does not always favor “max everything.” The industry just likes how simple that slogan sounds.

Let’s go through what the data actually shows—and where the usual white-coat-financial-guru script falls apart.

The Core Myth: Pre‑Tax Is Always Better

The typical script:

- Max your 401(k)/403(b).

- Max your 457(b).

- Max your defined benefit/cash balance plan.

- Then maybe a backdoor Roth and taxable investing.

All pre‑tax first “to lower your taxes.”

Here’s the problem: lowering this year’s tax bill is not the goal. Minimizing lifetime taxes and maximizing spendable after‑tax retirement income is.

For many physicians—especially dual‑income couples, people planning partial early retirement, or those with big pensions—cramming everything into pre‑tax accounts backfires. Why?

Because you’re not deducting at 37% now and withdrawing at 12% later.

A more realistic pattern I see:

- Earning years: effective marginal federal + state often ~32–37%.

- Retirement years for aggressive savers: required minimum distributions (RMDs) push you back into 22–32%+ brackets, sometimes higher if you add:

- Social Security taxation creep

- IRMAA surcharges on Medicare

- State taxes

- Possible future rate hikes (yes, rates are scheduled to increase in 2026 if laws don’t change)

If you build a huge pre‑tax war chest and no Roth/taxable balance, you’ve set yourself up for:

- Very limited control over taxable income in retirement.

- RMDs that force withdrawals when you do not need the money.

- Higher marginal tax rates on every extra dollar you want to spend.

You did not avoid taxes. You deferred them to a time when the IRS has more control than you do.

Account Types: What You’re Really Choosing Between

Strip away the acronyms. You’re basically choosing between three buckets:

Pre‑tax (Traditional)

401(k), 403(b), 457(b), defined benefit/cash balance, traditional IRA (if deductible).- You get a deduction now.

- Growth is tax‑deferred.

- Withdrawals taxed as ordinary income later.

- Subject to RMDs (except some government 457s with different quirks).

Roth

Roth 401(k), 403(b), Roth IRA, backdoor Roth IRA, Roth conversions.- No deduction now.

- Growth tax‑free.

- Qualified withdrawals tax‑free.

- No RMDs for Roth IRAs (Roth 401(k) still has RMDs unless rolled over).

Taxable brokerage

Plain old individual/joint account.- No deduction now.

- Dividends and interest taxed annually.

- Long‑term capital gains and qualified dividends often at lower rates.

- Enormous flexibility (timing of sales, tax‑loss harvesting, step‑up in basis at death).

Here’s the part people skip: the optimal mix of these three is not “max all pre‑tax, then shrug.”

A more honest question is: “Given my income, career horizon, state taxes, and retirement goals, which mix gives me the best lifetime after‑tax outcome and flexibility?”

That answer is often: not maxing every pre‑tax option.

The Trap of Oversized Pre‑Tax Balances

I’ve run this scenario more times than I can count.

Dual‑physician couple:

- Both make ~$350k.

- Max 401(k)s (pre‑tax), 457(b)s (pre‑tax), and a large cash balance plan.

- Invest aggressively.

- Minimal Roth, small taxable account.

Fast‑forward to age 65:

- Combined pre‑tax balance: $5–7M is very common in the projections.

- Social Security: $50–70k/year combined.

- Pension or hospital‑funded plan: often something modest but real.

They feel rich. Then we run RMD projections.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 73 | 220000 |

| 76 | 260000 |

| 79 | 310000 |

| 82 | 370000 |

| 85 | 430000 |

| 88 | 480000 |

Those RMDs, plus Social Security, push them into high brackets again. They’re forced to realize taxable income they do not actually need just to satisfy the IRS.

That means:

- Higher federal and state tax bills.

- Higher IRMAA surcharges on Medicare premiums.

- Less ability to “dial down” income in years they want to do big Roth conversions, harvest capital gains at 0–15%, or qualify for certain tax credits/benefits.

They followed the “max everything” rule. It worked—until it didn’t.

When Maxing Pre‑Tax Makes Good Sense

I’m not anti‑401(k). I’m anti‑thoughtless‑401(k).

For some physicians, maxing all pre‑tax vehicles is optimal. Examples:

Early‑career, high‑earning, planning standard retirement age

- You’re 32, earning $450k, single, in a high‑tax state.

- You’re likely in the absolute highest marginal bracket you’ll ever see.

- You’re not planning to save aggressively enough to hit $6–7M+ in pre‑tax by 65.

- Maxing pre‑tax now is usually a win, especially if you also build Roth via backdoor and later conversions.

Short career horizon with big present income Think surgical subspecialist planning to retire or at least scale back at 50.

- You’ll have 15–20 years of very high income, then a long window of much lower income pre‑Social Security.

- That “gap” is perfect for Roth conversions at low brackets, turning pre‑tax into Roth deliberately.

- Maxing pre‑tax while you’re at peak earnings and then aggressively converting between, say, 50–65 can work out very nicely.

Strong chance of meaningfully lower retirement spending If you know you’ll live significantly below your working income—say you earn $600k but will comfortably live on $120–150k/year—yes, the probability is higher that your retirement marginal rate will be lower than now. Pre‑tax then looks better.

But even in those cases, I still want a balance: some pre‑tax, some Roth, some taxable, unless there’s a very compelling reason otherwise.

When “Max Every Account” Starts Hurting You

There are three big red flags that you might be overdoing pre‑tax:

1. You Have Almost No Taxable Account

If you’re 45, making $500k+, with:

- $1.5M in pre‑tax

- $150k in Roth

- $50k in taxable

…you’re in the classic “asset rich, flexibility poor” trap.

Short of tapping Roth or taking 10% penalty pre‑59½, you’ve locked most of your assets behind “retirement age” walls. That’s a problem if:

- You want to go part‑time in your 40s or 50s.

- You want to take a sabbatical, start a business, or change countries.

- You need to bridge to 59½ without huge tax penalties.

Ironically, physicians chasing “financial freedom” often make themselves less free in their 40s and early 50s by maxing every tax‑advantaged thing and starving their taxable account.

2. Your Projected RMDs Crush Lower‑Bracket Opportunities

If we project RMDs at 73+ and they alone fill the 22–24% brackets (or higher), your ability to:

- Do Roth conversions at low brackets,

- Realize long‑term capital gains at 0–15% rates,

- Fine‑tune your income year‑to‑year,

…shrinks dramatically.

You gave up today’s 32–37% rate for “future lower rates” that, in reality, never arrive.

| Strategy | Pre-Tax at 65 | Roth at 65 | Taxable at 65 | Projected RMD at 73 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Every Pre-Tax | $5.5M | $0.3M | $0.3M | ~$230k/year |

| Balanced Contributions | $3.5M | $1.5M | $0.8M | ~$150k/year |

Same total wealth in many simulations. Very different tax control.

3. You’re Ignoring Roth Options Inside Plans

I still see doctors in 2025 putting all of their 401(k)/403(b) contributions pre‑tax, while also complaining they’re “afraid of future tax hikes.”

You cannot have it both ways.

If you genuinely believe your future rates (personal or legislative) will be higher:

- You should be favoring Roth, not blindly maxing pre‑tax.

- Especially in years where your taxable income dips: maternity/paternity leave, fellowship, job change, sabbatical, business loss year, major charitable giving year.

The idea that “maxing every account” automatically means pre‑tax is just inertia from the 1990s.

The Cash Balance / Defined Benefit Plan Problem

This is where a lot of physicians get pushed into excess.

Cash balance or defined benefit plans let you stash very large pre‑tax sums—often $50k–$200k+ per year—on top of your 401(k). Sounds like free candy.

In reality:

- These plans are almost always 100% pre‑tax.

- They front‑load the problem of concentrated future taxable income.

- They’re less flexible (funding rules, actuarial assumptions, ongoing advisor/admin fees).

A cash balance plan can make sense if:

- You’re in your peak earning years.

- You truly want to save that much.

- You’ve already:

- Built a solid taxable portfolio.

- Consistently used backdoor Roth.

- Thought through an exit/conversion strategy later.

If instead you:

- Have modest or no taxable account,

- Have minimal Roth,

- Are not interested in detailed retirement tax planning,

…then maxing a cash balance plan on top of everything is often just doubling down on future tax pain.

I’ve sat with 60‑year‑old docs with $4–6M locked up in pre‑tax between 401(k) + cash balance, then watched them flinch when they see how little control they’ll have over taxes in their 70s. “But my advisor told me to max all this for 15 years.” Of course they did. They charge based on assets.

When Not Maxing Is Rational, Not Lazy

Let’s spell this out clearly: You’re not “failing” at retirement planning if you choose not to max some account.

Here are situations where it’s rational:

Case 1: You Need Liquidity and Optionality in the Next 5–15 Years

You’re 38, hospitalist, burned out, planning:

- Possible switch to telemedicine,

- Geographic move,

- Partial financial independence in your 40s.

You might be better off:

- Maxing employer match (always).

- Using some combination of:

- Partial 401(k) contributions,

- Maxing backdoor Roth,

- Heavier taxable investing.

You’re buying flexibility. You avoid locking money away where you pay penalties to access it exactly when career change is most likely.

Case 2: Your Projected Pre‑Tax Balance Will Already Be Huge

Run the numbers: at 7% annual return, 25–30 years of maxing just a 401(k) as a physician puts you squarely in multi‑million pre‑tax territory.

Now add:

- 457(b)

- Cash balance plan

- Employer contributions

You don’t get extra points for hitting $8M in pre‑tax instead of $5M while starving your Roth/taxable pipelines.

At some point the priority shifts from “How big can I make this?” to “How do I keep this from causing a tax headache later?”

Case 3: You’re In A Transitional Tax Year

A few examples I’ve actually seen:

- Academic surgeon going to private practice with huge income jump next year. That one low‑income gap year is perfect for Roth contributions or conversions, not stuffing more pre‑tax.

- Couple taking a year off between training and attending-hood to travel. Their taxable income drops dramatically. Perfect time for Roth focus.

- Major one‑time deduction year (big charitable gift, business loss, cost segregation on real estate). Again, that can make Roth contributions or conversions significantly cheaper than usual.

In those years, “max every pre‑tax account” is the wrong play.

How To Decide: A Simple Framework

You don’t need a 40‑page Monte Carlo printout to decide whether to max everything. You at least need a framework that beats “because my accountant said so.”

Ask yourself:

What’s my current marginal bracket (federal + state) vs my realistic retirement bracket?

- If you’re in the top brackets now and expect clearly lower later, pre‑tax looks good.

- If you’re already on track to have very high RMDs, more pre‑tax might not be helping.

What is my current mix of pre‑tax vs Roth vs taxable?

- If pre‑tax is >70–80% of total investable assets and you’re under 50, I start getting suspicious.

- If taxable is tiny and you want early optionality, that’s another red flag.

Do I have an intentional Roth strategy?

- Backdoor Roth each year?

- A plan for conversion windows (early retirement, sabbaticals, gap years)?

Do I realistically need this extra tax‑advantaged capacity to reach my goals?

A lot of you are on track already just maxing a 401(k) and saving in taxable. The 457(b) or cash balance plan then becomes “nice to have if it fits the overall tax picture,” not mandatory.

Here’s an oversimplified comparison for context:

| Strategy | Pre-Tax / Year | Roth / Year | Taxable / Year | Flexibility Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Every Pre-Tax | $88k | $12k | $0 | Low |

| Balanced (My Bias) | $60k | $24k | $16k | High |

| Roth-Heavy (Special Case) | $40k | $40k | $20k | Very High |

The “best” one depends on income, state, age, burnout risk, and your retirement timing. But you see the point: max‑pre‑tax isn’t the default answer.

Don’t Forget the Behavioral Side

There’s also a human factor nobody in the spreadsheet crowd talks about.

I’ve seen physicians grind extra calls and miserable shifts “because I want to max my 457 and cash balance this year,” while:

- Ignoring creeping burnout,

- Postponing vacations or parental leave,

- Delaying hiring help at home or in their practice.

Then they tell me, at 52, “I’m done. I would’ve worked longer if I hadn’t pushed so hard at 40–45.”

If maxing every account buys you marginal tax savings but shortens your career by years because you’re miserable, that is a terrible trade. Financial advice that treats you like a tax-optimizing robot is bad advice.

Sometimes the right move is:

- Hit your 401(k) match.

- Do your backdoor Roth.

- Save a reasonable amount in taxable.

- Use the rest to actually improve your day‑to‑day life.

You’re not failing retirement. You’re refusing to sacrifice your 40s on the altar of perfect tax deferral.

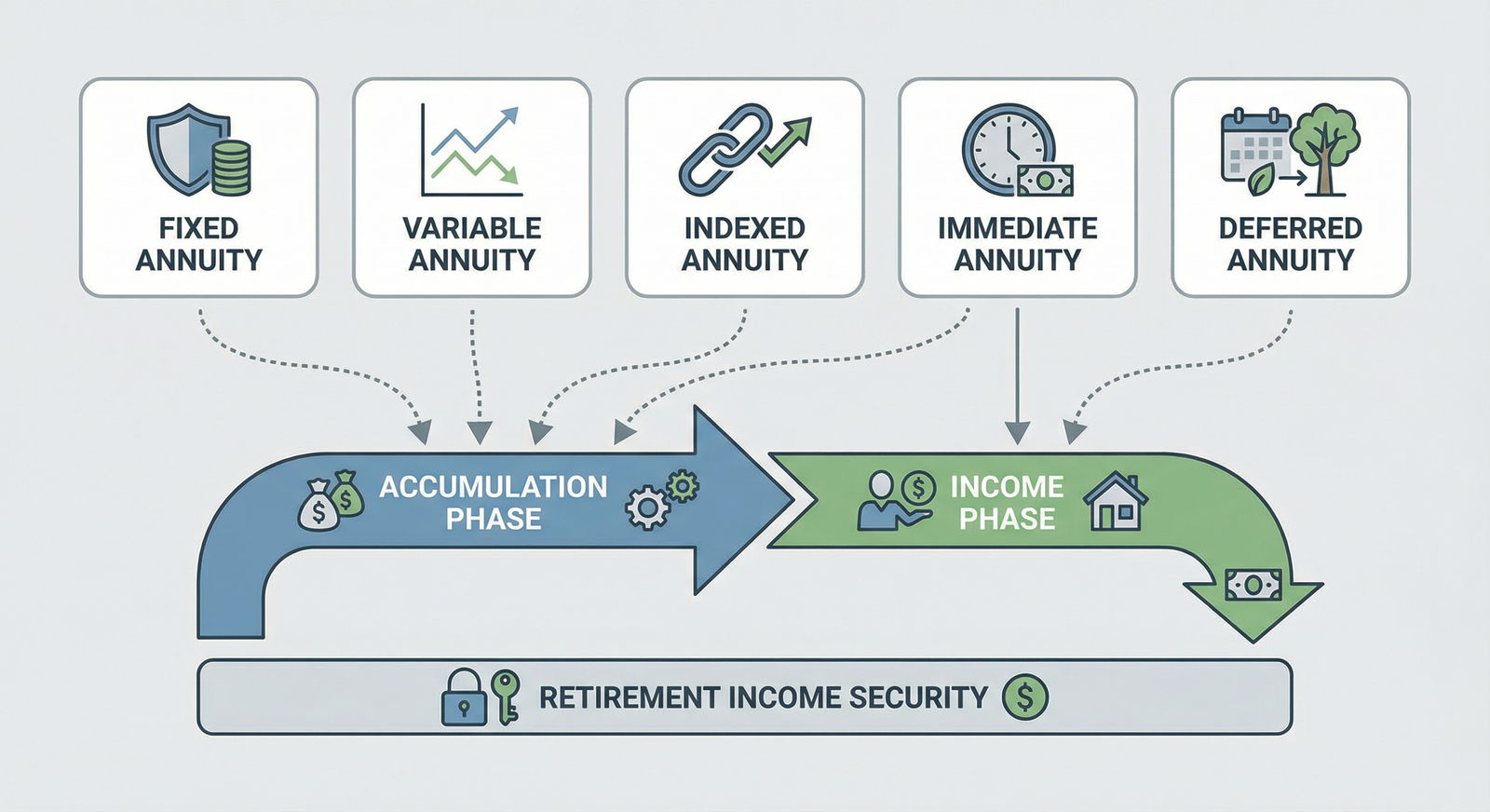

Visual: How Income Mix Affects Retirement Tax Flexibility

One last snapshot. Two 65‑year‑old retired cardiologists, same total net worth, very different account mixes.

| Category | RMD Income | Roth Withdrawals | Taxable Withdrawals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Tax Heavy | 70 | 5 | 25 |

| Diversified | 40 | 30 | 30 |

Same dollars. The diversified one has choices. The pre‑tax‑heavy one has obligations.

A More Honest Rule of Thumb

If you want a bumper‑sticker rule, use this instead of “max every account”:

Max your match. Then build a balanced mix of pre‑tax, Roth, and taxable that fits your likely lifetime tax path and your need for flexibility.

That means:

- Questioning automatic pre‑tax contributions once your projected RMDs start looking scary.

- Valuing taxable accounts as a feature, not a failure.

- Using Roth strategically—not just as an afterthought via backdoor.

- Being willing to say “No, I’m not maxing that extra pre‑tax option because it doesn’t help my actual life.”

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start Year |

| Step 2 | Favor Roth and taxable |

| Step 3 | Shift some to Roth and taxable |

| Step 4 | Pre tax focus ok |

| Step 5 | Review mix yearly |

| Step 6 | Current tax bracket high |

| Step 7 | Projected RMD problem |

Key Takeaways

- “Max every retirement account” is not a universal good; for many physicians it just converts today’s tax bill into a larger, less controllable tax bill later.

- A deliberate mix of pre‑tax, Roth, and taxable—aligned with your income trajectory, RMD projections, and lifestyle goals—beats blindly stuffing every pre‑tax option.

- Flexibility has value. Sometimes the rational, mathematically sound choice is to not max another pre‑tax account and instead buy yourself options, sanity, and control over future taxes.