Seven Toxic Study Habits That Quietly Derail Your First Med School Year

What if the reason you feel constantly behind in first year is not that the material is too hard, but that your study habits are quietly sabotaging you?

I have watched smart, capable new M1s burn out or barely scrape by. Not because they were lazy. Because they carried premed habits into an environment where those habits become toxic. And they did not notice the damage until they were already underwater.

Let’s walk through seven of the worst offenders. If you recognize yourself in any of these, fix them now—before exam blocks and Step pressure magnify the consequences.

1. Rewriting Notes Like It’s a Craft Project

You know this one. The student who spends four hours making a single “perfect” Anki deck from lecture. Or rewriting slide notes by hand in five colors. Or turning a 50‑slide lecture into an 18‑page “summary.”

On paper, it feels productive. You are working hard. You are “organizing.”

In reality? You are burning time on low-yield tasks while the content pile grows.

The toxic pattern looks like this:

- You watch or attend the lecture.

- You tell yourself you cannot “really start studying” until you’ve cleaned and organized your notes.

- That organization takes forever.

- By the time you “finish,” you are mentally fried and have no energy left for actual learning or retrieval.

The result: You have gorgeous notes and mediocre recall.

The mistake here is confusing exposure with learning. Your brain does not care how pretty the page looks. It cares how often it has to struggle (productively) to retrieve and apply information.

A simple comparison, because this is where people fool themselves:

| Approach | Time Use | Exam-Day Recall |

|---|---|---|

| Rewriting notes | 70–80% passive | Weak, fragile |

| Making minimal cues | 30–40% active | Better, but spotty |

| Practice + retrieval | 60–80% active recall | Strong, durable |

What to do instead (without becoming a robot):

- Cap “note cleaning” time. For example: 30–45 minutes per lecture block, max. When the timer ends, you move on.

- Force yourself into active recall early. After lecture, close the slides and write out what you remember on a blank page. Then check what you missed.

- Only make cards or notes for things you actually needed help remembering—not every sentence from the slides.

If you end most days with the feeling, “I was busy all day but I cannot answer questions,” your note habit is part of the problem. Stop worshipping aesthetics. Start caring about whether you can explain renal physiology without looking.

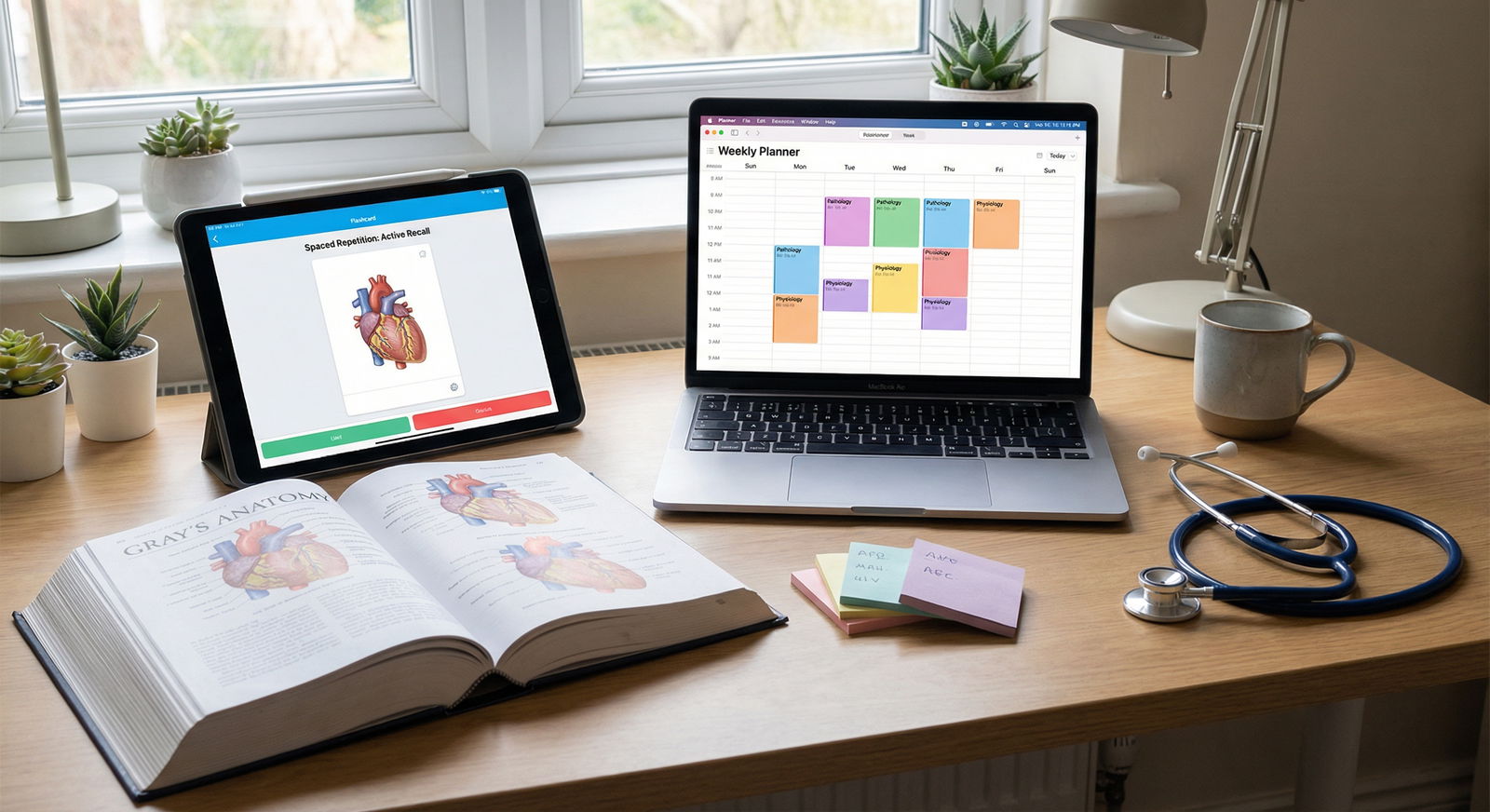

2. Treating Spaced Repetition Like Optional Extra Credit

Here is the quiet killer: letting Anki (or any spaced repetition system) turn into a guilt graveyard.

This usually happens in three steps:

- You hear every upperclassman say, “Use Anki, it saved me.”

- You download someone’s 30,000‑card deck or build gigantic personal decks.

- Reviews climb to 800+ per day, your life explodes, you stop doing them, and the system collapses.

Now you are stuck in the worst possible place:

Too many cards to keep up, too much guilt to quit, and too little time to actually learn.

Let me be blunt:

Overcommitting to spaced repetition is as destructive as ignoring it completely. Both extremes destroy consistency.

This is what I have seen repeatedly: the students who succeed with spaced repetition are boringly moderate. They:

- Add fewer, higher‑yield cards.

- Tolerate the feeling of “not capturing everything.”

- Respect daily reviews like brushing teeth—non‑negotiable and not dramatic.

Here is how review overload creeps up, then buries you:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Week 1 | 80 |

| Week 2 | 140 |

| Week 3 | 220 |

| Week 4 | 310 |

| Week 5 | 420 |

| Week 6 | 580 |

| Week 7 | 760 |

| Week 8 | 900 |

By week 5–6, you are drowning.

The mistake: you confuse “more cards” with “more prepared.” That is false.

You want fewer, high-yield cards you actually see and remember, not a sprawling deck you constantly reset.

Better approach:

- Cap new cards per day. For many M1s, 40–80 carefully chosen new cards per day is sane. Above that, you are usually padding, not learning.

- Delete aggressively. If a card is confusing, redundant, or low-yield? Delete it. Do not baby bad cards.

- Protect review time. Put a hard review window in your day (for example: 7:30–8:30 a.m. plus 30 minutes in the evening). You treat that as sacred, exam block or not.

If your Anki app makes you anxious every time you open it, your system is broken. Fix the system before it drives you into avoidance and last‑minute cramming.

3. “I’ll Catch Up on the Weekend” – The Fantasy That Never Happens

The most common first-year lie:

“I’m just behind for now. This weekend, I’ll catch up.”

No, you will not. Not the way you are imagining.

The academic structure of most M1 programs makes this fantasy especially dangerous. You get:

- 3–6 dense lectures per day

- Lab, small groups, clinical skills sprinkled in

- Continuous new content regardless of how behind you are

By Friday, you are maybe 10–15 lectures behind. You tell yourself you will use Saturday and Sunday to get “fully caught up.” Then:

- You are exhausted.

- Real-life tasks (laundry, groceries, calls, mental reset) eat half the day.

- You slog through a few lectures, but your brain checks out after hour three.

End result: you start Monday slightly less behind, but still behind. And now you are also more tired.

I have watched this pattern snowball across a block, especially before anatomy or neuro exams. The students stuck in this loop slowly shift their “catch up” target further and further ahead:

- “After this week.”

- “After this exam.”

- “After this block.”

The “after” never arrives.

The fix is not “work harder on weekends.” That is how you burn out by October. The fix is ruthless, unromantic daily minimums.

Think in terms of non-negotiables, for example:

- Every day: I will truly learn today’s material, not just attend it.

- If I fall behind: I prioritize understanding over coverage. I choose what to not watch rather than pretending I will see everything.

This is where people get uncomfortable: you may need to deliberately skip some low-yield lecture videos or parts of them. Yes, really. If your school records everything, there is usually more content than you can deeply internalize.

The toxic habit is pretending you can “catch it all later.” You cannot. And trying to will cost you the chance to master what actually matters.

4. Passive Binge-Watching Lectures Like Netflix

Another quiet derailment: treating recorded lectures as background noise.

The contour of this mistake:

- You speed lectures to 2x or 2.5x.

- You tell yourself you are being efficient.

- You sort of listen while answering texts, checking email, maybe doing dishes.

- You end the video having “watched” but not processed 70% of the content.

Then exam week hits. You vaguely remember seeing those slides. But you cannot work through questions that twist or apply those facts.

I have heard first-years say, “But I watched every lecture twice,” as if that is proof the exam was unfair. It is not. It just tells me how much passive learning you leaned on.

You need friction. Cognitive effort. The feeling of, “Wait, do I actually know this?”

Lecture watching without forced retrieval is almost pure illusion.

Use a simple test after each lecture:

- Close the slides.

- On a blank sheet or document, write: “If I had to explain this to a confused classmate in 5 minutes, what would I say?”

- Give yourself 5–10 minutes and actually do it. No notes.

If you stare at the page or write generic fluff, you did not learn the lecture. You just watched it.

A better pattern:

- Use active pause: watch 5–10 minutes → pause → summarize out loud or on paper → resume.

- If you are at 2x speed but pausing constantly to think and recall, fine. If you are at 2x speed just to “get through stuff,” you are faking productivity.

- Limit repeat full re-watches. Rewatching entire 1‑hour lectures is almost always low-yield. Target specific unclear segments instead.

If you find yourself bragging about how many hours of lecture you watched, rather than how many questions you can correctly answer, your priorities are backwards.

5. Ignoring Practice Questions Until Right Before Exams

This one derails a frightening number of otherwise bright students.

They tell themselves:

- “I need to learn everything first, then I’ll do questions.”

- “Questions are just assessment, not learning.”

- “I do not want to see low scores; it will freak me out.”

So they avoid practice questions for 2–3 weeks of a block. Then, five days before the exam, panic hits. Now they try to cram through a huge question bank section in a weekend. Their performance is shaky. They panic more.

The irony: the thing they avoided because it felt bad (questions) was exactly what would have helped solidify their knowledge and reveal gaps early.

Here is what usually separates the students who adjust well in M1 from those who constantly feel blindsided:

Early question users:

- Start doing questions within the first week of a block.

- Accept low scores as normal while material is fresh.

- Use questions to guide what they review, not as a final exam.

Late question users:

- Wait until they feel “ready” (they never really do).

- Experience every missed question as a personal failure.

- Learn too late that they misunderstood core concepts.

You want to be the first group. “But I do not know anything yet” is not a valid excuse; the entire point of early questions is to expose that.

Practical guardrails:

- From week 1: Aim for a small, daily question dose tied to whatever content you covered that day (even 10–20 questions).

- Treat wrong answers as gold. Tag them, write quick explanations in your own words, connect them to lecture points.

- Resist the urge to save “the good questions” for right before the exam. Your brain needs the reps early.

If you walk into an exam having done almost no questions in that style or system, you did this to yourself. Do not make that mistake.

6. Sacrificing Sleep Like It’s a Competitive Flex

There is a weird, toxic bravado in some med school cultures: bragging about how little you slept before an exam block. As if cognitive impairment is a badge of honor.

You will hear things like:

- “I only slept three hours last night but at least I finished the lectures.”

- “I have not had a full night of sleep in two weeks.”

- “I don’t have time to sleep eight hours, that’s for chill specialties.”

This is nonsense. Counterproductive, self-sabotaging nonsense.

Sleep is not a luxury in first year; it is one of the few variables you fully control that has massive impact on memory consolidation. If you shortchange it consistently, you pay twice:

- Your ability to encode new material each day drops.

- Your ability to recall previously studied material tanks.

Here is roughly what happens to your effective learning time as sleep decreases:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 8 hrs | 100 |

| 7 hrs | 85 |

| 6 hrs | 65 |

| 5 hrs | 40 |

Yet, in exam weeks, people happily trade two hours of sleep for two extra hours of half‑awake “studying” that barely sticks.

The deeper mistake: treating your brain like a bottomless drawer you can keep stuffing facts into, rather than a living system that needs downtime to organize and strengthen what you learned.

Here is a simple rule I have seen high-performing students hold to, and it works:

- Night before normal school days: 7–8 hours, non-negotiable.

- Night before exams: minimum 6 (and many still aim for 7, yes, even for big exams).

If your plan for passing relies on chronic short sleep, your plan is bad. You might get away with it for one exam. Maybe two. But by mid-year, your baseline functioning will be worse, and you will start forgetting things you “definitely studied.”

Protect sleep. Anyone who mocks that is someone you should not emulate academically.

7. Studying in Social Chaos and Calling It “Accountability”

The last quiet saboteur: trying to do serious, deep work in the middle of social noise, under the excuse of “group study.”

I have sat near first-years in the library who spent three hours “studying together.” What actually happened:

- 30% of the time: talking about how stressed they were.

- 30%: complaining about specific lecturers, NBME, or the curve.

- 20%: comparing scores and resources.

- Maybe 20%: doing real focused work, usually fragmented.

Then they walked out saying, “We studied all afternoon.” No, they mostly socialized in the vicinity of open notes.

Study groups are not inherently bad. But they are frequently misused.

When they become harmful:

- The group size is too large (more than 2–3).

- No one has a clear goal for the session.

- People are at very different preparation levels, so the discussion either goes too slow or too fast for someone.

- The primary feeling in the room is anxiety, not focus.

A lot of this is driven by fear of isolation. You do not want to be “the one studying alone” because it feels like everyone else knows something you do not. So you attach yourself to a chaotic collective pattern that feels safer.

Here is the better, quieter pattern I see in students who actually thrive:

- They do the bulk of their learning alone, in controlled environments, without their phone.

- They use small, targeted group sessions 1–2 times per week to explain difficult topics to each other, quiz, or clarify problem areas.

- They leave any setting that turns into venting or score‑comparing, even if that feels socially awkward.

If a “study session” leaves you more confused, more anxious, and behind on your own plan, that is not accountability. That is sabotage disguised as camaraderie.

You are allowed to protect your focus. You are allowed to say, “I am going to study solo this afternoon; I’ll catch you later.” The people who respect that are the people worth keeping close.

Pulling This Together Without Burning Out

Let me be clear: the solution to these toxic habits is not grinding yourself into dust. It is the opposite. It is stripping away the fake productivity so the work you do actually counts.

One practical way to see how these habits may be undermining you is to list how many hours you pour into each kind of activity during a typical week:

| Activity Type | Hours/Week | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Passive lecture watching | 18 | Often overused |

| Note rewriting | 10 | Usually too high |

| Spaced repetition | 6 | Often too low or chaotic |

| Practice questions | 4 | Needs to start earlier |

| True active recall | 3 | Typically underutilized |

Most struggling M1s, when they are honest, find a similar imbalance. Way too much passive time. Not enough retrieval and application.

Rebalancing does not happen overnight. But it starts with one decision: you stop lying to yourself about what is and is not working.

You stop saying, “This is just how I study.”

You start asking, “Does this actually improve my exam performance and long-term recall?”

A useful way to audit your own process over a block:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start of Block |

| Step 2 | Choose core resources |

| Step 3 | Set daily non-negotiables |

| Step 4 | Weekly self-check |

| Step 5 | Cut low-yield habits |

| Step 6 | Maintain current plan |

| Step 7 | Pre-exam review & adjust |

| Step 8 | Falling behind? |

You are not stuck with the habits you used as a premed. Med school is different. The volume, pacing, and stakes are different. Trying to brute-force your old methods is how you quietly derail your first year without realizing it until the grades come back.

Three Things to Walk Away With

- Busy is not the same as effective. If your days are full but your recall is weak, your habits—not your IQ—are the problem.

- Early, consistent active work (spaced repetition, questions, recall) beats late, panicked marathons of passive review every single time.

- Protect your core resources: time, sleep, and attention. Any habit that burns those without clearly improving your performance is not “your style.” It is a liability.