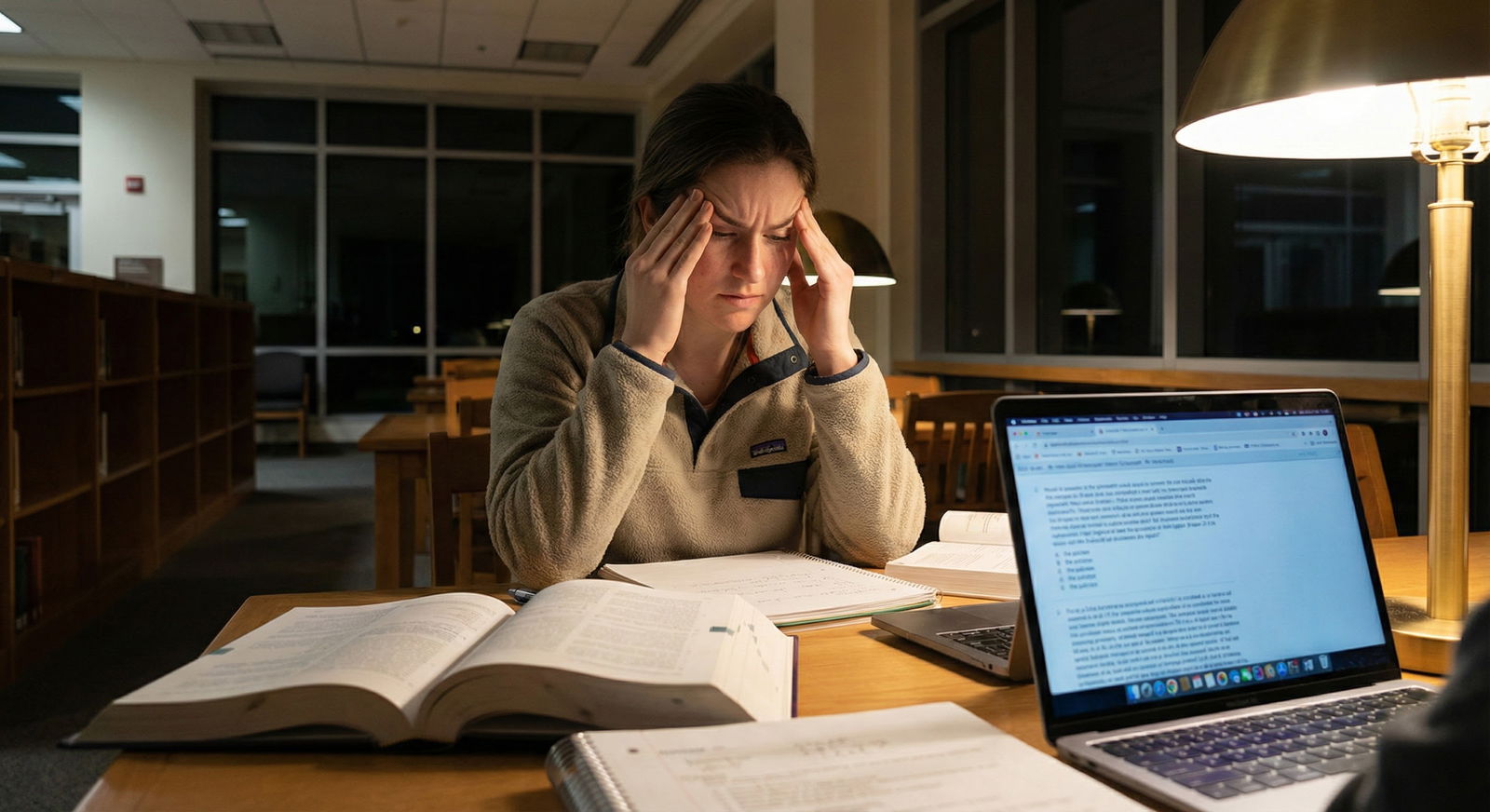

The USMLE is not just testing your knowledge; it is deliberately probing your anxiety circuits.

Certain question formats are practically engineered to spike your heart rate, blank your mind, and make you forget basic physiology you knew in second year. And it is not random. There are very specific patterns that repeatedly trigger panic in otherwise well-prepared students.

Let me break this down specifically: which question formats do this, why they hijack your brain, and how to neutralize them so they stop owning your score.

1. The “Wall of Text” Vignette That Eats Your Brain

You know the one. 16–22 lines. Multiple labs. Radiology. Med list. Three consultants’ opinions. A paragraph about the guy’s dog. Then a vague question stem at the end.

This format is common across Step 1/2/3 and NBME forms. And it absolutely shreds anxious test-takers.

Why this format triggers panic

This type attacks you on three levels:

Working memory overload

Your prefrontal cortex can juggle maybe 4–7 chunks of data. These vignettes often throw 15–25 separate data points: age, sex, meds, vitals, exam, labs, imaging, time course, comorbidities.

Under stress, your effective working memory drops. So what happens? You start re-reading. Then re-reading again. Time pressure climbs. Panic follows.Signal vs noise confusion

The exam writers intentionally pack in semi-relevant details. Things that could matter but do not. Students with anxiety feel compelled to search for meaning in every line. You end up in cognitive quicksand, trying to justify each sentence instead of extracting the pattern.Time perception distortion

Long stems consume visual space on the screen. Your brain equates “big block of text” with “this will take forever.” You glance at the timer, see it ticking, and your sympathetic nervous system kicks in.

End result: you either rush and miss key information, or you freeze and burn 3+ minutes on a single item.

How to dismantle this format

You are not going to change the stems. You change the way your brain meets them.

Reverse reading order

Train yourself to briefly scan:- The question at the bottom first (e.g., “Next best step”, “Most likely diagnosis”, “Mechanism of action”)

- Then the answer choices to see the domain (diagnosis vs management vs mechanism).

Now when you read the stem from the top, you already know what you are hunting for. This alone saves huge cognitive load.

Chunking and bracketing

As you read, mentally (or lightly on scratch paper) mark:- Demographics: age, sex, pregnancy status

- Time course: acute vs chronic

- Vital “red flags”: hypotension, altered mental status, hypoxia

- One-liner summary: “55-year-old smoker with hemoptysis, weight loss, and hypercalcemia.”

You compress 20 lines into one sentence. That one sentence is what you truly reason with.

Practice under real time pressure

Most students “review” by pausing, looking up concepts, or taking 4–5 minutes per question. Then they are shocked on exam day.

You must practice 40-question and 80-question blocks timed, with no pausing, until wall-of-text vignettes feel like “just another question,” not “the panic one.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Short Stem | 10 |

| Medium Stem | 30 |

| Long Stem | 65 |

| Very Long Stem | 85 |

2. “All Options Are Plausible” – The Ambiguous Management Question

These are the classic Step 2/3 killers:

- Every answer looks reasonable.

- You could argue for half of them in real life.

- The question stem is long, and the last line says: “Which is the best next step in management?”

This is where highly conscientious students melt down.

Why this format triggers panic

Perfectionism vs “best”

The exam is not asking for “a reasonable option”. It wants the single best evidence-based next step. Anxious, perfectionistic students start catastrophizing:

“If I pick B but they wanted C, that means I don’t know how to manage X. What else am I missing?”

Your brain jumps from the micro-decision to a global judgment of your competence.Cognitive dissonance with real-life medicine

Residents will tell you, “Honestly, you could do either of those in real life.” So your mental model of medicine (“multiple reasonable paths”) clashes with the exam’s model (“one clean correct answer”). That mismatch creates doubt about your intuition.Overweighting minor details

These questions hinge on small, but crucial, details:- Hemodynamic stability

- Pregnancy status

- Contraindications buried in the med list

- Time window (onset of chest pain, stroke symptoms)

Under panic, you either:

- Miss the critical detail entirely, or

- See it but do not trust that it really matters.

How to break this one

Verbalize the “big rule” first

Before looking at answer choices, say (quietly, in your head):

“Stable angina + positive stress test → next step is coronary angiography.”

Or, “Suspected PE in a pregnant, stable patient → start with V/Q scan.”

You anchor yourself on the algorithm before you see tempting distractors.Use a strict tie-breaker hierarchy

When multiple answers seem reasonable, use a mental priority list:- Does any option directly address an immediate life threat?

- Is there an option that is diagnostic + therapeutic (higher value)?

- Does any option violate a clear contraindication?

- Does any option “jump steps” (doing an advanced or invasive test before a basic one)?

You resolve ambiguity systematically instead of emotionally.

Deliberate practice with “why the others are wrong”

When you review these questions, do not stop after “Oh, A was correct, got it.”

Force yourself to explain why B, C, D, and E are specifically worse choices.

Over time, your pattern recognition shifts from “everything looks ok” to “that one is slightly more guideline-concordant.”

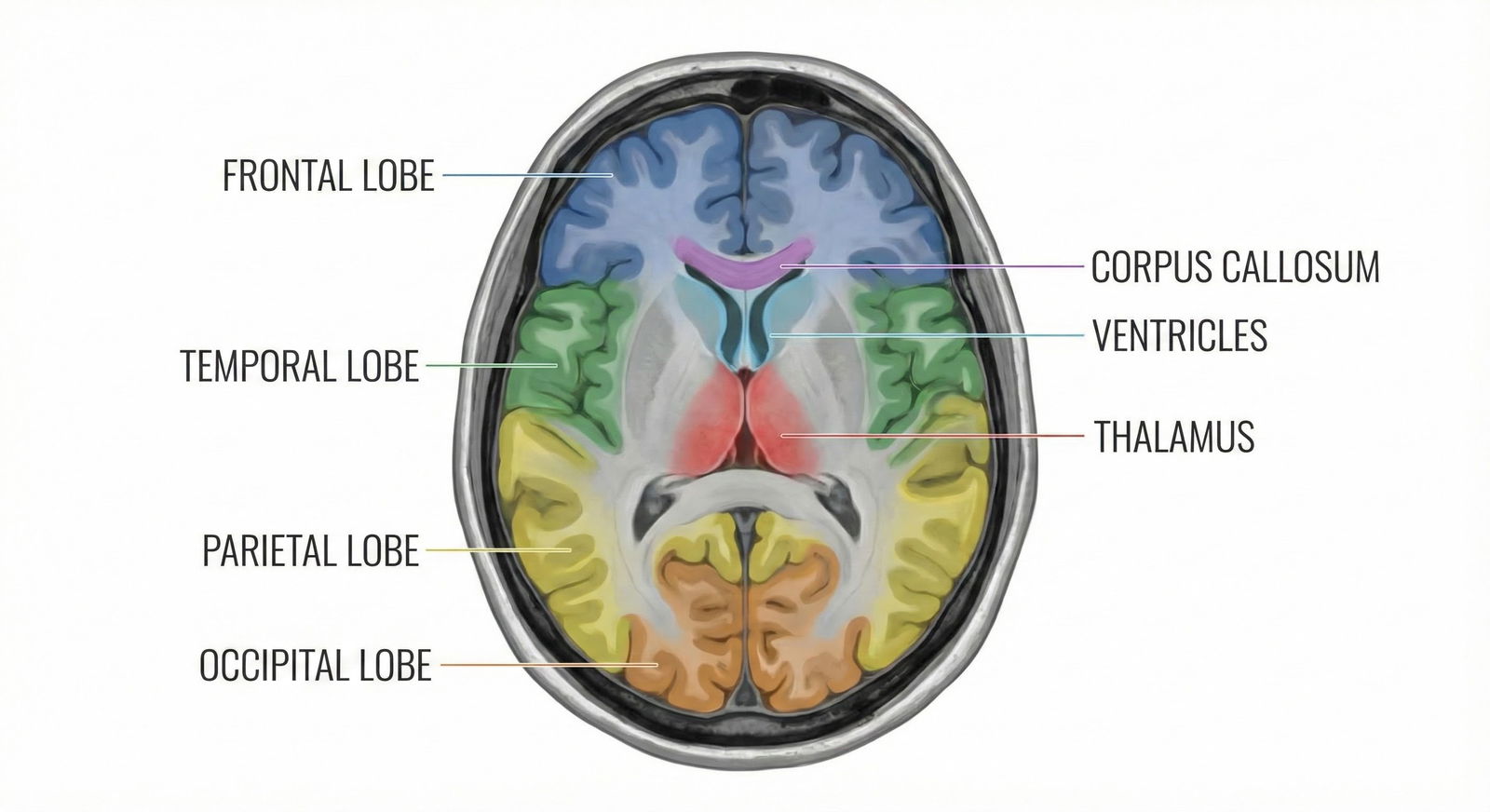

3. Anatomy & Neuroanatomy Image Questions – The Visual Ambush

Cross-sectional CT at the level of the basal ganglia. MRI of a spinal cord lesion. Microscopic slide of glomerulonephritis. Derm photos with subtle differences. These are classic anxiety traps, especially for Step 1.

Why these formats trigger panic

“I am not a radiologist” identity narrative

Many students have quietly decided they are “bad at anatomy” or “bad with images.” That narrative activates the second the image loads. You are in a hole before you even start.Forced dual-processing

These questions make you:- Visually interpret the image

- Map it to 3D anatomy in your head

- Then connect it to a clinical syndrome or lesion

Three steps instead of one. Under anxiety, your processing speed slows, and the chain breaks anywhere along the path.

Fear of missing tiny, low-contrast details

Subtle loss of gray–white differentiation. Small, hyperintense lesion. Slightly enlarged ventricles. Students start “hunting” pixel by pixel instead of looking for major patterns. That scanning behavior screams anxiety.

How to tame imaging questions

Use a fixed 3-step script

For neuroimaging, for example:- Step 1: Identify the plane (axial, coronal, sagittal) and side (L vs R).

- Step 2: Name 3–4 obvious landmarks (lateral ventricles, thalamus, internal capsule).

- Step 3: Ask: “What structure or territory looks abnormal or asymmetric?”

You constrain your focus and prevent aimless scanning.

Start with very basic image drills

Not question banks. Just structure ID:- Neuroanatomy atlases (e.g., Netter’s neuro, cross-sectional resources)

- Basic MRI/CT “normal anatomy” slides

Do 10–15 images a day, labeling, until normal becomes automatic. Only then layer clinical vignettes on top.

Accept approximate, not perfect, localization

The exam often wants: “Internal capsule” vs “Cerebral peduncle” vs “Medial medulla.”

You do not need millimeter-perfect accuracy to answer the majority of questions.

Build categories: cortical vs subcortical vs brainstem vs spinal cord, then region within that. Panic comes from chasing exactness when the question only needs approximate.

4. “What Is the Mechanism?” – Molecular Detail Under Time Pressure

These are the nightmare Step 1 style stems:

- Long biochem pathway

- Obscure enzyme name

- Unlabeled graph of receptor binding or dose–response

- Then: “Which of the following best explains this finding?”

Students often freeze here even when they know the concept cold.

Why this format spikes anxiety

Abstract, non-clinical framing

You spent two years translating basic science into clinical reasoning. These questions force you back to micro-level: receptors, pathways, kinetics. It feels like undergrad again. That identity dissonance is uncomfortable.Graph + passage + mechanism = three representations

You must interpret the graph (visual), link to a concept (verbal), then pick a mechanistic statement (verbal but highly specific). High switching cost cognitively.“I should know this” shame

These questions often cover “high-yield” pathways: glycolysis, TCA, pharmacodynamics, immunology. When you do not instantly recall the detail, shame kicks in. Shame is one of the most powerful cognitive saboteurs on exam day.

How to manage mechanism questions

Translate the graph into a sentence first

Ignore the answer choices. Look at the graph and force yourself to produce a single sentence:

“The drug shifted the curve to the right without changing Vmax → competitive antagonist.”

Or, “Patient’s enzyme activity drops sharply beyond 40°C → heat-labile enzyme defect.”

Only then look at the answer options.Anchor on archetypes, not minutiae

Nearly all these questions fall into a limited set of archetypes:- Competitive vs noncompetitive inhibition

- Upregulation vs downregulation of receptors

- Gain-of-function vs loss-of-function mutations

- Increased sensitivity vs decreased sensitivity

If you can classify the pattern into one of these, you do not need to remember every specific enzyme cofactor.

Rehearse aloud during study

Mechanism questions are easier if you have physically said these sentences multiple times:

“A competitive antagonist shifts the curve to the right, Km increases, Vmax unchanged.”

Spoken, not just read. You want those pattern sentences to be almost reflexive.

5. Multi-Step Reasoning: “Diagnosis + Next Step + Pathophysiology” in One

The exam loves stacking tasks:

“Patient presents with X. What is the most likely pathophysiologic mechanism?” where:

- First, you must diagnose the condition.

- Then recall the key pathology.

- Then map that to a described mechanism, not the name of the disease.

Or:

“Which of the following is the best next step?” where identifying the condition is implicit. They never actually name it in the stem.

Why this format melts people

Serial dependency

If you are wrong on step 1 (diagnosis), you are dead for step 2 and 3. Every subsequent reasoning step inherits the initial error. Under time, you do not go back and reassess step 1. You double down.Hidden sub-questions

These questions look like single items, but they are actually triplets. Your brain senses the complexity even if you do not articulate it: “This feels like a lot.” Cue anxiety.Fear of partially knowing

Many students can narrow down the diagnosis, but not articulate the precise mechanism statement. That “I sort of know it but not exactly” feeling is deeply uncomfortable for high-achievers. They equate uncertainty with failure.

How to handle stacked reasoning questions

Make step 1 explicit: “Name the disease”

Literally write (or whisper in your head):

“This is acute interstitial nephritis.”

“This is Guillain–Barré.”

“This is HOCM.”

Then answer the actual question. This forces a conscious checkpoint instead of a blurry, half-formed impression.Prebuild disease → mechanism one-liners

For common conditions, have a single go-to mechanistic sentence:- “AIN: Drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction causing eosinophilic infiltration of the interstitium.”

- “Graves: Autoantibodies stimulating TSH receptors → increased thyroid hormone production.”

- “DIC: Widespread activation of coagulation → consumption of clotting factors and platelets.”

You are mapping from disease name to mechanism formula, not re-deriving the mechanism from scratch.

Practice “backwards” questions

Deliberately solve questions in review by:- Starting with the mechanistic statement

- Then asking yourself which disease this would produce

This trains bidirectional mapping and reduces the serial dependency trap.

6. Ethics / Biostats / Abstract Reasoning – The “Soft” Questions That Hurt More

The irony: lots of students score worse on ethics and statistics than cardiology or nephrology. And they panic more.

Typical triggers:

- Vignettes about consent, confidentiality, cultural beliefs

- Biostat tables: sensitivity/specificity, likelihood ratios, hazard ratios

- Abstract EBM questions about study design, bias, intention-to-treat

| Domain | Common Format Trigger |

|---|---|

| Long Vignettes | Multi-page clinical scenarios |

| Management | All answers plausible |

| Imaging | Cross-sectional CT/MRI |

| Mechanisms | Graphs + pathways |

| Biostats | 2x2 tables, hazard ratios |

Why these “soft” domains trigger outsized panic

False belief: “Everyone else finds this easy”

You will hear classmates say, “Ethics is free points.” That is a lie for many people. But you internalize it. So when you hesitate on an ethics question, you feel disproportionately behind.Ambiguous wording

Many ethics questions are intentionally phrased with emotionally charged content (end-of-life, abortion, cultural conflict). The anxiety comes not from knowledge, but from fear of “picking the wrong side” morally.Math insecurity

Biostats questions trigger old math trauma. Fractions. Ratios. Logs. Students convince themselves they “just do not get stats.” That belief kicks in faster than their actual knowledge.

How to blunt ethics and biostats panic

Internalize the tiny ethics rulebook

USMLE ethics is not your personal morality. It is a bounded set of principles:- Respect patient autonomy

- Maintain confidentiality unless clear harm to self/others

- Do not abandon the patient

- Avoid dual relationships and conflicts of interest

- Disclose errors honestly and clearly

Almost every ethics item is a variation on these. Memorize that mini-rulebook, then classify each question: “Which principle is being challenged?”

Convert biostats to pattern recognition, not math

For example, know these by reflex:- Sensitivity = rule out (SnNout)

- Specificity = rule in (SpPin)

- Hazard ratio > 1 = increased risk in treatment/exposed group

- Confidence interval that crosses 1 (for ratios) or 0 (for differences) = not significant

You should see a 95% CI of 0.7–1.3 around a relative risk and immediately think: “Not significant. Null cannot be rejected.” No arithmetic needed.

Practice 10–15 ethics/biostats questions per week

Small, steady exposure reduces the “rare, scary” effect. Over 2–3 months, these questions shift from panic triggers to “comfortable freebies.”

7. What Panic Actually Does to Your Performance (Physiology, Not Vibes)

Let me be blunt. Panic is not just “feeling stressed.” On exam day, it has concrete, testable effects:

- Working memory shrinks – You cannot hold as many data points, which is lethal for multi-line vignettes.

- Processing speed slows – Each question takes longer, compressing your time for later blocks.

- Error checking collapses – You skim the answer choices and click your first “feels right” option. Premature closure.

- Attention narrows – You fixate on one detail and miss the key phrase that flips the diagnosis.

| Category | Working Memory Capacity | Processing Speed | Error Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calm | 90 | 90 | 85 |

| Mild Anxiety | 70 | 75 | 60 |

| Panic | 40 | 50 | 30 |

You can be “knowledge-ready” and “score-unready” if you ignore this.

So, what do you do about it?

8. Concrete Anti-Panic Techniques Mapped to Each Format

This is where people usually go vague. “Breathe deeply.” “Stay positive.” That is not enough. You need techniques tied to specific triggers.

For long vignettes

- Read question + choices first.

- Summarize the case in one line out loud (quietly): “Elderly man with weight loss, painless jaundice, and Trousseau sign = pancreatic adenocarcinoma.”

- Hard cutoff: If you hit 90 seconds and you are re-reading, force yourself to pick best answer and mark it. Do not let one question eat your block.

For ambiguous “best next step” items

- Decide the diagnosis explicitly.

- Ask: “Is the patient stable?” Yes → outpatient/less invasive. No → stabilize first.

- Apply the step-up principle: do the least invasive, most informative test that will actually change management.

For images

- Plane, side, landmarks, asymmetry. That order. Every time.

- If truly lost: lean on clinical info in the stem more than the image. The image is often supportive, not primary.

For mechanisms and graphs

- One sentence to describe the graph before choosing.

- Immediately identify archetype: “This is classic competitive inhibition curve,” etc.

- If utterly uncertain, pick the answer that describes direction of change correctly (up vs down, right vs left shift). That alone raises odds.

For stacked reasoning questions

- Write or whisper the diagnosis name.

- Ask: “What is pathognomonic or classic for this disease?” That often points to the mechanism.

- If stuck, consider backwards reasoning: which option, if true, would most cleanly produce this vignette?

For ethics / biostats

- Name the ethical principle in play: “autonomy vs beneficence,” “nonmaleficence,” etc.

- For stats, identify what the number is: OR, RR, HR, sensitivity, specificity. Many errors happen before the math.

- If uncertain in ethics, lean toward: preserve autonomy, maintain confidentiality, avoid lying, do not abandon.

9. Building “Format Immunity” Before Test Day

You cannot fully avoid panic in a high-stakes exam. But you can drastically reduce how reactive you are to these specific USMLE question formats.

Three very practical moves:

Deliberate format practice blocks

Once a week, do a 20–40 question block focused on one format:- Only long vignettes.

- Only ethics/biostats.

- Only imaging questions.

Do not mix. You are not testing knowledge here; you are retraining your threat response to the format itself.

Post-block format review, not just concept review

After each block, tag:- Where did my heart rate spike?

- Which stems made me re-read?

- What answer choice style (“most appropriate,” “initial step,” “most likely explanation”) threw me?

Then craft 1–2 micro-rules for each pattern. You are debugging your test-taking behavior, not just your content gaps.

Simulate worst-case mentally before the real exam

Visualize:- Opening a block of 40, first three are horrible long stems.

- You blank on a biostats question.

- You completely misread an image.

Then, in your visualization, you watch yourself:

- Take one slow breath.

- Apply your script (question-first, one-line summary, etc).

- Move on at 90 seconds if necessary, with no drama.

The brain responds better to threats it has already “seen.”

You are not “bad at tests” and you are not uniquely fragile. You are dealing with a very specific set of question formats designed to push your cognitive limits. Once you see the pattern, you can attack it deliberately.

With these format-specific tools in hand, you are better equipped to keep your prefrontal cortex online while everyone else is silently melting down at question 17. The next step is integrating this into a disciplined block-by-block study plan that stress-tests your system before the actual exam. But that is a conversation for another day.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. I always run out of time on long vignettes. Should I skip them and come back later?

If a vignette looks massive, do not auto-skip. Give it a structured 60–90 seconds using your script (question first, one-line summary, key findings). If by 90 seconds you are still lost, pick your best option, mark it, and move on. Saving every long vignette for later often means you never return to them with a clearer head; you just face them more exhausted and more panicked.

2. How many imaging questions should I do to feel comfortable before Step 1/2?

Aim for at least 10–15 pure anatomy/imaging ID questions per week for 8–10 weeks, plus whatever appears naturally in your main Qbank. The point is not thousands of radiology questions. The point is structured, repeated exposure to common planes and landmarks until “normal” and “classic pathology” feel familiar.

3. I panic when two management options both seem correct. What is the fastest tie-breaker on exam day?

Use a quick three-step filter:

- Does any option obviously stabilize an unstable patient? That wins.

- Is one option less invasive / lower risk but still answers the clinical question? Prefer the lower-risk test if both are guideline-supported.

- Does any option require information you do not yet have? If so, it is usually too “far down the algorithm” to be the best next step.

4. Should I flag every question I feel unsure about?

No. Over-flagging is a subtle anxiety trap. Limit marking to questions where:

- You genuinely think a second read may change your answer, and

- You are confident you will have at least 5–7 minutes at the end of the block.

If you are routinely finishing blocks with under 3 minutes left, you should mark far fewer questions and focus on making your best decision the first time.

5. How do I distinguish productive fear from paralyzing panic while studying?

Productive fear sounds like: “I missed several biostats questions; I should schedule a focused review session.” It leads to specific action.

Paralyzing panic sounds like: “I am terrible at this; I am going to fail the exam.” It is global, absolute, and does not suggest a next step. When you catch the second pattern, interrupt it immediately: stand up, move, reset your breathing, then re-approach the problem with a concrete micro-goal (e.g., “I will master sensitivity/specificity today”).