The myth that only first‑author, high‑impact, basic science papers “count” for competitive specialties is trash. Dangerous trash.

If you’re sitting there thinking, “All my research is fluff, they’re going to see right through it,” I’ve been in that exact brain spiral. The late‑night CV scroll. The “compare with classmates” doom session. The “my friend has 14 pubs and I have a poster at a regional meeting with my name 7th out of 9” panic.

Let me be blunt: programs don’t sit around saying, “This project was retrospective and single‑center, therefore this applicant is unworthy.” That’s not how it works. But there are ways “fluffy” research hurts you — and it’s not always the way you think.

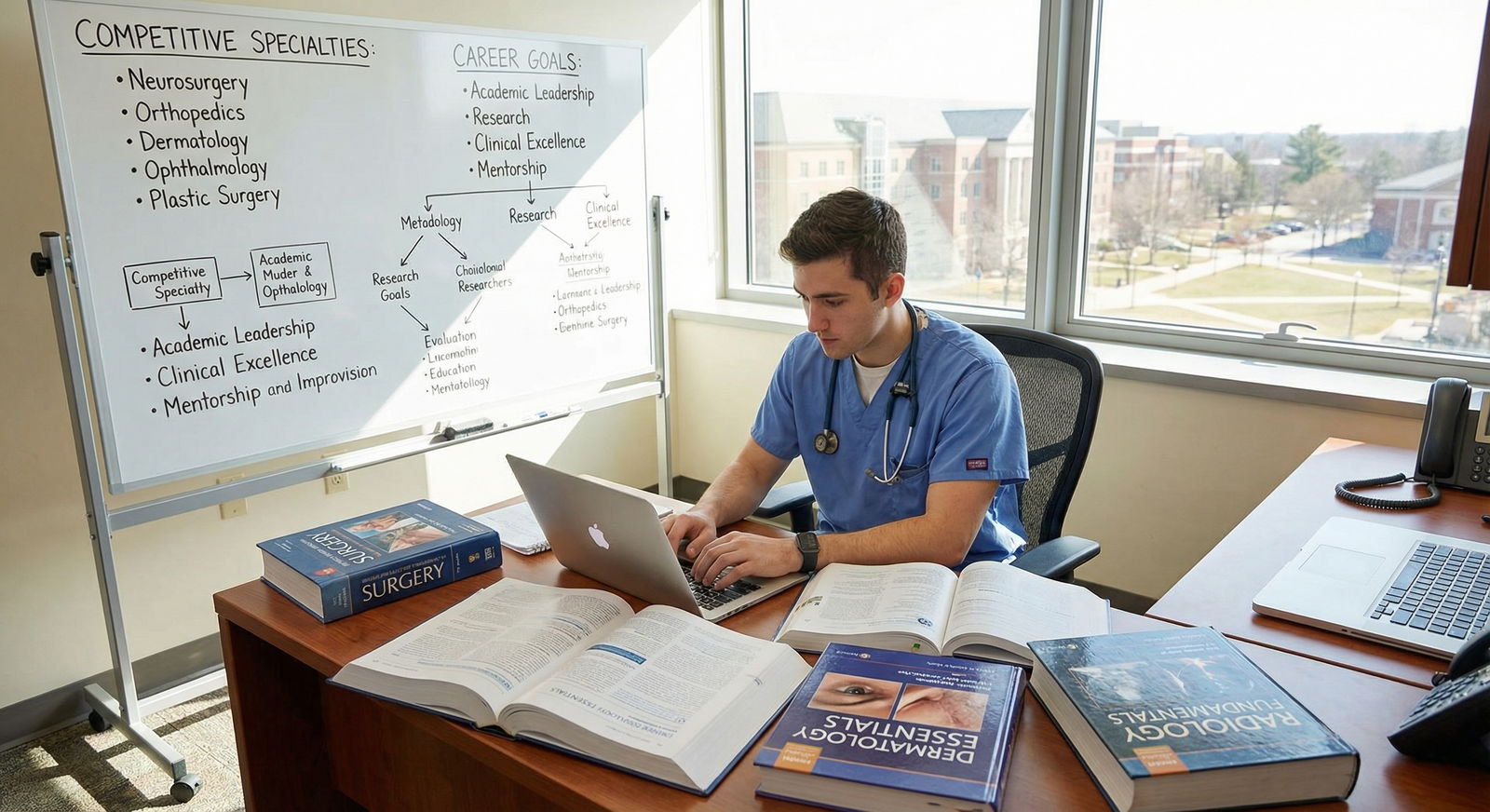

Let’s pick this apart properly, because competitive fields (derm, plastics, ortho, ENT, ophtho, rad onc, neurosurg) feel like a different universe, and the bar feels absurd.

First: What “Counts” vs What Feels Fake

You’re probably thinking of your projects and mentally grading them:

- Chart review that never got published

- Quality improvement project your school forced on you

- Case report that 17 people are on

- Abstract that went to some random regional poster session

- Basic science lab where you pipetted a lot and then the paper died

And you’re thinking: zero impact. Zero points.

Here’s the part people don’t tell you because everyone wants a simple scoreboard. Programs don’t actually evaluate research the way applicants do. They don’t just count PubMed IDs and sort.

They care about three things, in different proportions depending on specialty:

- Can you follow through on complex, long‑term work?

- Can you talk intelligently about what you did and why it mattered?

- Does your research pattern match the story you’re selling about your future in that field?

That’s it. Not “did you cure cancer as an MS3.”

Where people get burned is when their application screams “I’m obsessed with dermatology,” but every research item is: “Random ED workflow, geri fall prevention, med ed survey, ICU QI… and one derm poster from a summer where I barely did anything.”

Is that fatal? No. But if you’re gunning for derm at a big academic place, that mismatch is exactly where your brain is right to feel uneasy.

Competitive Fields: What They Actually Expect

Let’s be honest about the landscape, because sugar‑coating doesn’t help.

For top‑tier academic programs in competitive specialties, you’ll commonly see applicants with long PubMed lists — especially in derm, plastics, neurosurg, ENT. It’s intimidating. It feels like everyone but you has a dedicated research year at Mass General and ten first‑author papers in JAMA.

Reality check: that’s the top slice of applicants. You’re seeing Instagram highlights, not the full match list.

Here’s a more grounded comparison:

| Specialty Type | Common Research Profile |

|---|---|

| Ultra-competitive (Derm, Plastics, Neurosurg) | Multiple projects, at least some in-field, 1–3 publications/abstracts, often a research year but not always |

| Competitive (ENT, Ortho, Ophtho, Rad Onc) | Mix of in-field + general projects, posters/abstracts common, a few publications helpful but not universal |

| Mid-competitive (Anes, EM, IM at top programs) | Any research is a plus, QI and clinical work valued, depth less critical |

| Less competitive (FM, Psych, Peds community) | Research nice but not required, even small projects can stand out |

| Academic-focused programs (any field) | Care more about trajectory and interest than raw count of papers |

So where does “fluff” fit?

Poster at a local conference? That counts.

Retrospective chart review? That counts.

QI project on discharge summaries? That counts.

It all counts — but it doesn’t all carry the same narrative weight. That’s the distinction you’re actually worried about without having words for it.

The Stuff That Feels Fluffy (And How Programs Actually See It)

Let’s walk through the usual suspects and I’ll tell you how an actual PD or faculty reviewer is likely to interpret them.

1. Case Reports

How it feels to you:

“I wrote up someone else’s interesting patient. This is fake research. Everyone knows it.”

How programs actually see it:

You saw something unusual, you followed instructions, you went through IRB or at least a submission process, you hit a deadline, you presented it. That shows engagement. Not Nobel‑level, but it’s a data point.

Red flag version: you list 8 case reports, all in totally unrelated fields, and can’t explain a single teaching point from any of them. That does scream padding.

2. QI Projects

How it feels to you:

“Mandatory school project on reducing discharge delays. Nobody outside my hospital cares.”

Programs:

“Welcome to real medicine.” Most attendings live in the world of broken processes. If you improved anything — discharge time, handoffs, medication reconciliation — that’s clinically real.

The question is: did you actually do anything, or was your role “input data and attend monthly meeting”? Both go on the CV, but only one helps you in an interview.

3. Retrospective Chart Reviews

How it feels:

“Everyone does these. They’re low‑tier.”

Programs:

Very normal. Bread‑and‑butter academic currency. What matters: Did it lead to an abstract or presentation? Can you talk about the hypothesis, limitations, and what you learned?

Someone who can clearly walk me through a chart review and what it showed is way more impressive than someone with a big fancy RCT on their CV who can’t explain their role.

4. “Work in Progress” With No Output

How it feels:

“I’ve started 5 things, nothing has been published, it’s all smoke.”

Programs:

If everything is “in preparation” and there’s zero poster/abstract/presentation anywhere, that starts to look suspicious. Not fluff — just not finished. It makes people wonder about follow‑through.

So if you’re panicking here, ask yourself: did anything result? Even a poster? A hospital research day? Those are not trivial. That’s the line between “strong attempt” and “vague promise.”

The Truth: The Real Red Flag Isn’t Fluff — It’s Fakeness

Let me be brutally honest because you don’t need more vague reassurance.

The thing that kills you is not doing small projects. It’s pretending they were massive, life‑altering, field‑changing contributions when they weren’t.

Programs are very used to seeing:

- 4th author on a QI poster

- Middle author on a small clinical study

- One pub, one abstract, a few presentations

That’s fine. Solid even. What makes them roll their eyes is:

- “Submitted to NEJM” written for a mediocre retrospective review

- Ten bullet points of “responsibilities” when you basically did data entry

- “First author” when the senior author remember you only edited the abstract

Your research doesn’t have to be huge. It has to be honest. And you need to be able to talk about it like a normal human, not a grant application.

Connecting “Fluffy” Research to a Competitive Field Without Lying

Here’s where your anxiety is actually on to something smart: if you’re going for something like derm, plastics, ENT, ophtho, neurosurg, or ortho and you don’t have much in‑field research, you’re at a relative disadvantage at some programs.

Not dead. Just behind some peers.

But you can still make a coherent story if you stop trying to force every project to look hyper‑relevant.

Say you have:

- One IM QI project (reducing readmissions)

- One ED case report

- One med‑ed survey on clerkship feedback

And you’re applying ENT.

You don’t say: “These all directly prepared me for ENT research.” That sounds fake.

You say something like:

“I didn’t start med school knowing I wanted ENT, so my early work is more general. But the through‑line is that I like problems where you can identify a specific failure point — a process, a diagnostic delay, a communication gap — and then track whether what you did actually changed anything. That’s ultimately what drew me to ENT: concrete problems, measurable outcomes, and procedures where you can see the result of your work right away.”

Now suddenly your “fluff” is showing them your mindset, not just your PubMed count.

When You Actually Need More / Better Research

There are situations where your gut anxiety is basically correct: you’d benefit from more, better‑aligned research.

The big ones:

- You’re applying to an ultra‑competitive specialty and have zero research anywhere, in anything

- You have “research” listed but can’t explain your role on any of it

- Everything is “in progress” with no output and you’re already in your dedicated application year

- You’re targeting top‑tier academic programs that explicitly care about scholarly output

Here’s the part nobody likes to admit:

You don’t need perfect research. You do need something you can own.

Even one well‑done, decently presented project in your target field — where you clearly understand the question, the methods, the results, and the implications — will often impress people far more than a messy list of 10 half‑baked things.

If you’re early enough (M2/M3, or even M4 taking a research year), aim for:

- At least one in‑field project where you had clear responsibility

- At least one concrete output: poster, abstract, or publication

- A mentor in that field who can actually speak to your work in a letter

Notice I didn’t say “three first‑author pubs in high impact journals.” That’s nice. Not mandatory.

How Programs Actually Use Your Research on Interview Day

Let me walk you through what happens on the other side, because that might calm some of the spinning.

Faculty get your application. They skim Step scores, grades, school, letters. They glance at your research list. And they usually pick one or two items to ask you about.

They’re not auditing your CV line by line with a red pen.

They might say:

- “Tell me about this QI project on discharge summaries.”

- “I see you did some chart review in nephrology — what was the main finding?”

- “How did you get involved with this case report?”

What they’re watching for is:

- Can you explain this without BS?

- Do you light up a bit when you talk about it, or does it sound like a chore?

- Do you understand anything about study design, limitations, or next steps?

- Does your description match what your CV implies?

If you can say, “Yeah, it wasn’t glamorous, but I learned X and we changed Y,” that lands far better than trying to pitch a small project as the next landmark trial.

A Quick Reality Check Using Numbers

Let’s put everything into a really simple mental model.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Field Alignment | 80 |

| Follow-through (output) | 70 |

| Quantity | 40 |

| Prestige of Journal | 30 |

This isn’t a real study, obviously. It’s the pattern I’ve seen over and over:

- Alignment and follow‑through matter more than raw count.

- Prestige is a bonus, not the baseline.

- Quantity helps at the extremes, but a modest amount of real, coherent stuff beats a wall of fluff.

You panicking about your “fluffy” QI poster? Honestly, it’s better than nothing, and it probably matters more than the fancy journal name you’ll never hit as a student anyway.

What You Can Do Right Now With the Research You Already Have

You can’t magically rewrite your history two months before ERAS. So here’s how to triage what you’ve got.

First, list every project and label three things for yourself:

- Was my role minor, moderate, or major?

- Did it produce anything (poster, abstract, presentation, pub)?

- Can I explain the question, method, and what we found without lying?

Then:

- Lead with the ones where your role was moderate/major and you have some output.

- Don’t bury a decent in‑field abstract under a giant list of half‑baked side things.

- In your personal statement and interviews, talk about what you learned, not how “important” the project was globally.

If something truly was fluff — like you attended one meeting and your name ended up on a poster you’ve never read — either leave it off or be very humble about it. “I contributed [X small part] to this project led by Dr. Y.” That’s safer than overselling.

And if you still have a bit of time pre‑application, consider pushing one thing across the finish line: a poster at a local meeting, a submitted abstract, a small write‑up. One well‑executed, small win beats five vague “manuscript in progress” lines.

The Relatable, Ugly Truth

You’re not crazy for worrying your research is fluff. A lot of med school “research” is exactly that — busywork, low‑yield, scattered projects, a CV arms race nobody remembers after Match Day.

But here’s the part your anxiety never says out loud: most programs know that. They lived through the same system. They’re not expecting students to show up with an R01‑level portfolio.

They’re trying to answer a few very human questions:

- Can I trust this person to take on projects and not disappear?

- Are they actually interested in this field, or are they just chasing status?

- Can they think a little beyond “p < 0.05”?

- Do their letters and stories back up what’s on this CV?

Your “fluff” can still answer those questions in your favor — if you stop pretending it’s something it’s not, and start owning what you actually did and learned.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | See research section |

| Step 2 | Neutral to mild negative |

| Step 3 | Pick 1-2 projects |

| Step 4 | Positive impression |

| Step 5 | Question effort or honesty |

| Step 6 | Any research listed |

| Step 7 | Applicant explains clearly |

FAQs

1. I have zero in‑field research for a very competitive specialty. Am I doomed?

No, but you’re fighting uphill, especially for the most academic programs. What matters now is how you compensate: strong away rotations, killer letters from people in the field, and a coherent explanation of how you got to this specialty. Programs like seeing in‑field research, but if everything else is strong and your research story still shows follow‑through and curiosity, you can absolutely still match — especially if you’re smart about your list and include a range of program types.

2. Is it worse to list “fluffy” research or to have no research at all?

Honestly, fluffy but real research is better than nothing, especially for competitive and academic programs. Even a small QI project or case report shows you engaged with something beyond classes and wards. The only time fluff backfires is when it’s obviously padded, dishonest, or you can’t explain what you did. Then it becomes a liability. If you did something minor, list it accurately and own that it was small. That’s still better than a blank section.

3. Does the journal name of my publication actually matter?

For residency, not nearly as much as students think. Of course a big‑name journal looks nice, but the number of applicants with NEJM/JAMA/Nature stuff is tiny and often not because they’re “better,” but because of who their mentors are. Programs care more about whether you contributed in a meaningful way and can talk about the work. A first‑author paper in a low‑impact, field‑specific journal can be more impressive than your name buried as 12th author on some huge, unrelated study.

4. How do I talk about small projects without sounding like I’m overselling them?

Be specific, be honest, and focus on your role and what you learned, not the “impact” of the work. Something like, “This was a small QI project in our clinic to reduce missed appointments. My role was collecting baseline data, helping design the reminder workflow, and presenting results at our local symposium. We reduced no‑shows by about 10%, and it made me realize how small systems changes can actually affect patient care.” That sounds grounded, real, and mature — and it makes your “fluffy” project feel substantial without pretending it changed national guidelines.

Key points: Most “fluffy” research still counts more than your anxiety says it does. The real risk isn’t small projects; it’s misalignment, no follow‑through, or overselling. Own what you did, connect it honestly to your story, and remember: they’re evaluating you, not just your PubMed search results.