What happens when you finally ask an attending for a clinical accommodation… and they say, “We don’t do that here”?

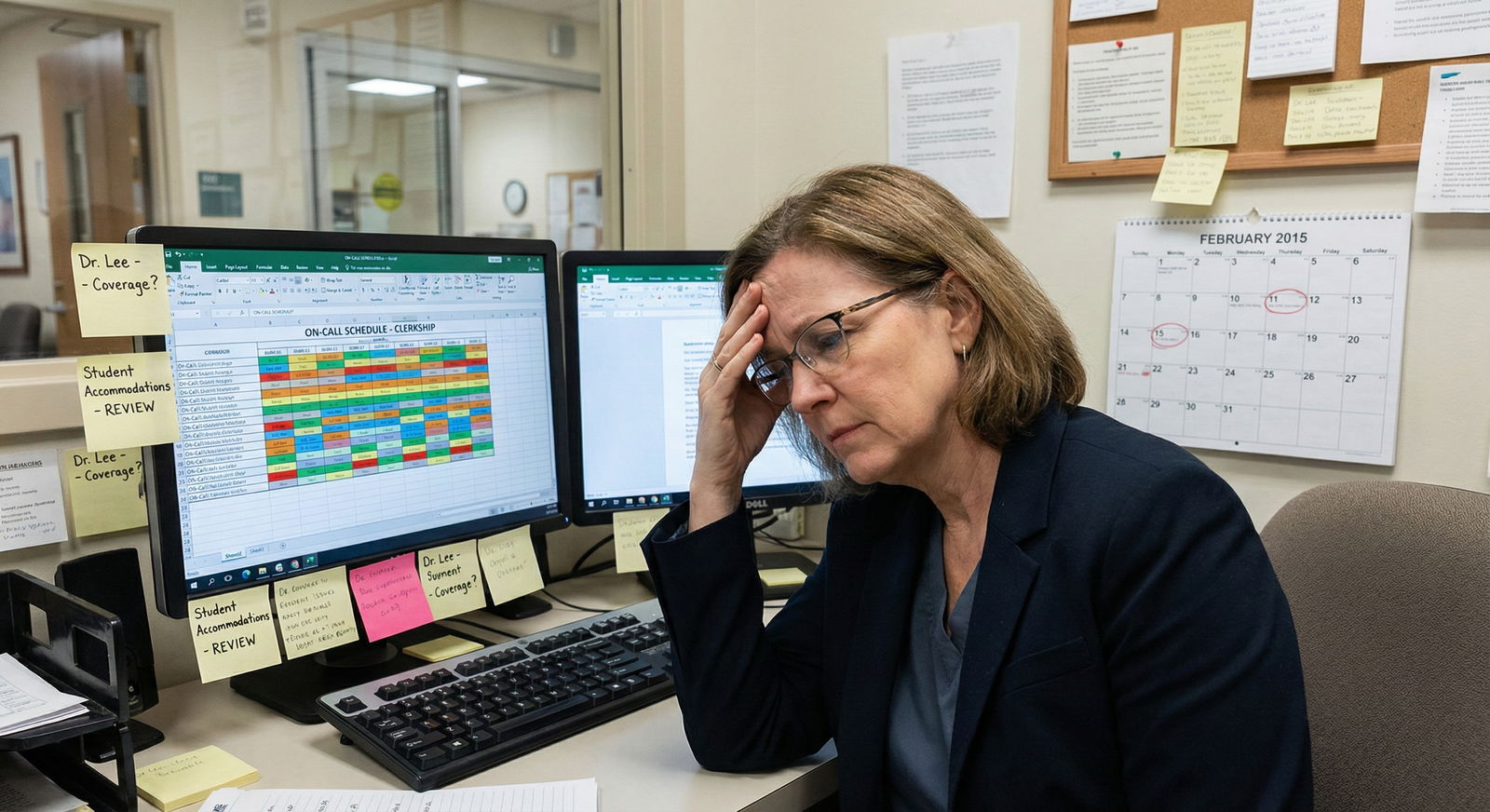

If you’re a medical student or trainee with a disability, chronic illness, pregnancy, or mental health condition, you’re walking a tightrope on rotations. You need modifications to be safe and functional. But you also know one bad comment on an evaluation can follow you for years.

So you hesitate.

Then you ask in the wrong way, at the wrong time, to the wrong person—and you pay for it.

Let’s stop that.

Below are the major mistakes I’ve watched students make when asking for clinical modifications—and how to avoid getting burned.

Mistake #1: Asking the Wrong Person First

The most common—and most dangerous—mistake: going straight to the attending as your first step for accommodations.

I’ve seen this play out:

You: “Dr. Smith, I have a disability and I need to leave by 5 for medical treatments three days a week.”

Dr. Smith: “We all have lives. We stay until the work is done. If you can’t, maybe this isn’t the right field for you.”

Now you’re cornered:

- No formal support

- An annoyed attending

- And no record that you ever requested an accommodation through the proper channel

Do not start with:

- A random attending on day 1 of a rotation

- A chief resident in the hallway

- A coordinator “just to see” what they think

You start with:

- Disability/Access Services (for students)

- GME / HR / Employee Health / ADA office (for residents, fellows, staff)

They:

- Document your disability or condition

- Help define specific, reasonable accommodations

- Put things in writing

- Usually send an official letter to the clerkship director, program director, or designated clinical lead

Only after that do you talk details with attendings. With backup.

Big red flag: If the school or program says, “Just work it out with your attending,” and offers nothing in writing. That’s institutional negligence in disguise. Push back. Get it formal.

Mistake #2: Oversharing Medical Details Instead of Functional Needs

You do not owe your attending your diagnosis.

Read that again.

You owe them:

- What you can do

- What you cannot safely do

- What modifications are needed for you to meet core requirements

What you don’t need to provide:

- Your full psychiatric history

- Your detailed neurologic workup

- Trauma history

- Medication lists

Here’s where students screw this up:

They feel guilty or scared, so they over-explain.

“Dr. Lee, I have PTSD and chronic migraines and I’ve had three concussions, and sometimes when I’m triggered I dissociate and… so I’m worried about codes.”

Now your attending is stuck holding information they didn’t need, aren’t trained to manage, and might unconsciously judge you for.

Better version:

“Dr. Lee, I have a documented disability and I’m working with Disability Services. I may occasionally need a brief step-away period from high-intensity situations when symptoms flare. The official plan is: if that happens, I’ll step out, let the resident know, and return when I’m able. I can participate in codes, but I need that flexibility built in.”

Short. Functional. Anchored to an official plan.

Avoid these oversharing traps:

- “Let me tell you everything so you’ll understand how serious it is.”

- Trauma-dumping to try to earn compassion.

- Giving them your diagnosis first, then trying to work backwards to your functional needs.

Attendings think in tasks and competencies. Translate your needs into those terms.

Mistake #3: Waiting Until You’re Already Failing or in Crisis

The worst time to ask for clinical modifications?

After:

- Multiple “needs improvement” comments

- A professionalism concern report

- A disastrous evaluation

- A meltdown in the OR hallway

By then, attendings frame your situation as:

- Performance problem

- Reliability issue

- Professionalism question

Instead of:

- Disability or health condition requiring accommodation

Here’s the trap: You tell yourself, “I’ll see if I can power through this rotation without asking for anything.”

So you:

- Push through severe pain or fatigue

- Hide your limitations

- Come in early, stay late, crash at home

- Then inevitably miss something, show up late, or appear disengaged

And now your first “accommodation” conversation happens with:

- The clerkship director

- Program director

- Associate dean After they’ve already heard complaints.

You want your first documented mention of accommodations to happen:

- Before the rotation starts

- Or as soon as you realize: “This is not sustainable or safe”

If your symptoms ramp up mid-rotation, you still do not wait until the eval is written. You:

- Email disability services / GME / HR: explain the change and ask for updated accommodations.

- Get things in writing.

- Then talk to the attending with that support behind you.

Silence until crisis is read as “no issue.” That’s how students end up repeating rotations or on probation when they could have been protected.

Mistake #4: Asking for Vague, Open-Ended “Flexibility”

One of the fastest ways to get a soft no is to ask for “understanding” instead of a specific, defined modification.

Vague asks sound like:

- “I just need some flexibility with hours.”

- “I may need to miss some things sometimes.”

- “If I could just leave early when I don’t feel well.”

An attending hears:

- “Unlimited exceptions”

- “Unpredictable availability”

- “Unclear expectations”

They will shut that down. Or agree verbally and then do nothing.

You need concrete, behavior-based requests, ideally already framed in your official accommodation letter.

Examples of clear requests:

- “My approved accommodation is a hard stop at 5 pm three days a week for medical treatment. I’ll arrive at 6 am and take signout early so I’m not missing learning time.”

- “I have an accommodation to sit during rounds and procedures when possible. That means I may use a stool in the OR and sit during long case discussions.”

- “My plan, as approved, is one protected 15-minute break in the afternoon to manage symptoms. If things are busy, I can delay it, but I do need it to happen before 4 pm.”

Specific. Time-bound. Operational.

Ask yourself before you speak:

“Could another attending read this request and know exactly what to do differently?”

If not, you’re still being too vague.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Asked too late | 70 |

| Went to wrong person | 65 |

| Overshared diagnosis | 55 |

| Vague request | 60 |

| No documentation | 50 |

Mistake #5: Treating Verbal Agreements as Protection

A friendly attending saying, “Sure, no problem” is not a legal protection. Or even a guarantee.

I’ve watched this blow up more times than I’d like:

- Student tells one attending verbally about a need.

- That attending is kind and flexible.

- Rotation changes. New attending. New expectations.

- No documentation. No record.

- Sudden “lack of professionalism” narrative appears in your file.

Also dangerous:

- Leadership changes.

- Program gets a site visit.

- Everyone suddenly pretends they’ve never heard of this “informal” arrangement.

If an accommodation or modification is important enough to matter when things go badly, it’s important enough to:

- Be documented

- Be approved through correct channels

- Be summarized in written form

At minimum, after a verbal agreement with an attending, you send a brief recap email. For example:

Subject: Summary of Clinical Accommodation Plan on Medicine Rotation

Dear Dr. Patel,

As we discussed this morning, based on my approved accommodation letter from Disability Services, I’ll be leaving the hospital by 5 pm on Mondays and Thursdays for medical treatment. I’ll arrive early to pre-round and complete my notes before leaving.Thank you again for your support,

[Name]

Now:

- You’ve created a written record.

- You’ve shown professionalism.

- If their behavior later contradicts this, you have evidence.

Big mistake: trusting a hallway conversation more than an email trail.

Mistake #6: Making It Sound Optional or Negotiable When It’s Not

Students often soften the request to sound “nice”:

- “If it’s okay, could I maybe…”

- “If it doesn’t cause too much trouble…”

- “I’ll try to avoid it, but sometimes…”

Here’s the problem: if you sound like you’re asking a favor, attendings feel allowed to say no.

You’re not asking for a favor. You’re implementing an approved, reasonable accommodation to access your education or job.

That doesn’t mean you show up with threats or legal jargon. But you do speak with clarity and firmness.

Wrong framing:

- “If it’s possible, I’d love to be able to sit down sometimes because of my condition.”

Better framing:

- “I have an approved accommodation that allows me to sit during longer procedures and on rounds when possible. So you’ll see me using a stool in the OR and sitting in the back of the room during some teaching sessions.”

Notice the difference:

- First one is a wish.

- Second is an implemented policy.

If the attending pushes back (“We don’t really do that here”), that’s when you calmly say:

“Understood. This was reviewed and approved by Disability Services / GME. I’ll reach back out to them and loop them in so we can find a plan that works for everyone.”

Do not start debating reasonable accommodations one-on-one with an annoyed attending. You’ll lose.

Mistake #7: Ignoring Rotation Culture and Timing

You can have a perfectly valid accommodation and still sabotage yourself by picking the worst possible moment and format to bring it up.

Terrible times to first mention modifications:

- Right before the first big surgery starts

- In front of the team on morning rounds

- During a code

- While the attending is obviously stressed or behind

Also bad: slipping it into casual conversation so vaguely that no one registers it as an actual plan. “Yeah, I sometimes have to go to appointments, but we’ll see.”

You need:

- The right time

- The right setting

- The right tone

Safer patterns:

- Email the attending a short, professional summary on day 1 or even the weekend before, referencing your official letter (which is usually sent from the institution).

- Then briefly reiterate in person at a quiet moment (after rounds, before clinic starts, during a natural lull).

Example email:

Subject: Brief Heads Up – Approved Clinical Accommodation

Dear Dr. Hernandez,

I’m looking forward to starting on your inpatient service this Monday. I wanted to let you know that I have an approved accommodation through our Disability Services office. The key components related to this rotation are:

– I may need to sit on rounds and during longer procedures.

– I have a protected 15-minute break in the afternoon to manage symptoms.I remain fully committed to meeting all clinical expectations and core requirements. I’m happy to briefly discuss how this will look on our service when you have a moment.

Best,

[Name]

Then when you see them:

“Just to follow up on my email about accommodations…”

Short, calm, no drama.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Symptoms or disability impact |

| Step 2 | Contact Disability or GME |

| Step 3 | Formal documentation |

| Step 4 | Accommodation letter issued |

| Step 5 | Notify clerkship or program director |

| Step 6 | Inform attending with written summary |

| Step 7 | Clarify logistics on service |

| Step 8 | Monitor and adjust with support office |

Mistake #8: Asking for Modifications That Remove Core Clinical Skills

Harsh truth: not every requested change is reasonable in a clinical setting.

Students sometimes ask for things that, if granted, would:

- Remove an essential function of the role

- Prevent proper evaluation of core competencies

- Make patient care unsafe

Examples that usually trigger resistance or flat-out no:

- “I can’t take call or nights at all for the entire rotation” (when that’s a core requirement for everyone)

- “I can’t interact with certain patient populations at all” in a required clerkship where that group is central (e.g., no children in pediatrics, no pregnant patients in OB/GYN, with no alternative plan)

- “I can’t do any procedures involving needles or blood” in surgery or EM without substitution

You need to be very clear:

- What’s essential for the role or rotation

- What’s negotiable in how you meet that requirement

Your mindset should be:

“How can I perform the required functions with support or modification?”

Not: “How can I be excused from all of the hard or triggering parts?”

This is where the disability office or GME is critical. They know what’s been approved before and what crosses the “essential functions” line.

Do not promise attendings you’ll never need exposure to something that’s central to the rotation. That sets up a conflict you can’t win.

A more realistic pattern:

- Adjust volume, duration, environment, and method

- Maintain core exposure and competency

Example:

- Maybe fewer overnight calls, not zero clinical nights ever.

- Maybe structured debriefs after particularly triggering cases, not total removal from that entire case category.

If you’re not sure whether your ask is reasonable, test it with disability services first, not with the attending.

Mistake #9: Forgetting That Some Attendings Will Handle This Badly

You can do everything “right” and still run into:

- Ableism

- Ignorance

- Power-tripping

- Old-school “suffer like I did” attitudes

Common problematic responses:

- “You look fine to me.”

- “Back in my day, we just pushed through.”

- “If you can’t handle this, you chose the wrong profession.”

- “We don’t give special treatment on my service.”

Huge mistake: taking these comments as the final word.

You do not debate your diagnosis. You don’t stay in that conversation alone.

Your moves:

- Stay calm in the moment. Do not escalate.

- Re-anchor: “This is an approved accommodation from Disability Services / GME.”

- Exit the argument: “I’ll reach out to them so we can clarify the plan.”

And then:

- Email disability services / GME / HR that same day.

- Document exactly what was said. Word for word, if you can.

- Include dates, times, and witnesses.

If it’s egregious (retaliation, threats, discriminatory remarks), loop in:

- The clerkship director

- Program director

- Or an ombudsperson

Red flag you don’t ignore:

An attending hinting that your request will hurt your evaluation if you “insist on it.”

That’s retaliation risk. Document it, immediately.

Mistake #10: Not Matching Your Behavior to Your Request

If you say:

- “I need to leave at 5 pm for health reasons”

and then:

- You’re staying until 7 pm to impress another attending

- Posting late-night gym selfies on public social media

- Volunteering for extra shifts when you like the team

It destroys your credibility.

Attendings notice inconsistency. They gossip. They compare notes.

Don’t make these credibility-killing mistakes:

- Treating your accommodation like a convenience on bad days and optional on good days

- Bragging about how “chill” your current attending is about your schedule

- Publicly doing high-intensity non-clinical activities that clearly contradict your claimed limitations (especially on public or semi-public social media)

You are allowed to have:

- Variable symptoms

- Good days and bad days

- A life outside medicine

But you must:

- Be consistent in how you apply your accommodations

- Avoid obvious contradictions in professional spaces

- Think before you overshare online or with peers who might repeat your words out of context

Your credibility is part of your protection. Don’t hand people easy excuses to dismiss your needs.

| Situation | Poor Request | Strong Request |

|---|---|---|

| Need early departure for treatment | "Sometimes I might need to leave early if I don't feel well." | "I have an approved accommodation to leave by 5 pm on Tue/Thu for medical treatment. I’ll arrive early and complete required work before leaving." |

| Need to sit during long cases | "I can't really stand for very long." | "My accommodation allows me to sit during longer procedures, so I’ll be using a stool in the OR when cases go beyond 60–90 minutes." |

| Need scheduled break | "I may need a break if my symptoms act up." | "I have one protected 15-minute break in the afternoon to manage symptoms. I’ll coordinate the exact time with the team daily." |

Mistake #11: Not Planning for Hand-offs Between Rotations

Your accommodation does not magically follow you from:

- Medicine to surgery

- Surgery to OB/GYN

- Inpatient to outpatient

- One hospital site to another

And yet students assume: “I told my medicine attending. So everyone knows.”

They don’t.

Then:

- New rotation.

- No one informed.

- Expectations reset to “standard.”

- Any behavior shaped by accommodations gets reinterpreted as laziness, disinterest, or unprofessionalism.

Your system between rotations:

- Confirm with disability services / GME which supervisors get the official letter each time.

- If their process is weak, advocate for automatic notification for each required clerkship or new site.

- For each new attending or service, send a brief repeat summary (like the email template earlier).

- Re-clarify logistics in person on day 1 or 2.

Do not think of this as “starting over.”

Think of it as protecting yourself from “we had no idea” when evaluations go sideways.

The 3 Things You Cannot Afford to Get Wrong

Keep this simple. If you remember nothing else, remember this:

Never go to the attending first and alone.

Start with Disability Services / GME / HR. Get formal, written accommodations anchored in institutional policy.Describe functional needs, not your entire medical history.

What you can and cannot do. What modifications look like in day-to-day tasks. Keep diagnoses and trauma details to people who actually need them.Put everything in writing and stay consistent.

Email summaries. Document pushback. Match your behavior to your requests. Protect your credibility and your record.

You’re not asking for special treatment. You’re asking for access.

Do not let fear or poor strategy turn a valid need into a preventable problem.