27% of U.S. adults have a disability, but only around 4–5% of physicians do.

That gap is not biology. It’s policy, bias, and lazy assumptions dressed up as “patient safety” and “technical standards.”

Let me be blunt: the idea that you “can’t” be a surgeon, anesthesiologist, interventionalist, or any other hands‑on physician with a disability is not evidence-based. It’s culture-based. And the culture is behind the times.

We’ll go straight at the big myths people whisper in hallways, say in “wellness” meetings, or hide in technical standards on the website no one reads.

Myth #1: “You can’t be a surgeon with a disability. It’s just not safe.”

The favorite line: “I totally support inclusion… but the OR is different. Lives are at stake.”

Here’s what the data actually says.

A 2016 study in Academic Medicine found that 2.7% of U.S. medical students self‑identified as having a disability. A follow‑up in 2019 showed that jumped to 4.6% as more schools updated policies and climates improved. Correlation is pretty obvious: better policies → more disclosure → more disabled trainees actually advancing.

We also have real surgeons with disabilities. Right now. Practicing. Examples, since people seem to need names to believe reality:

- A trauma surgeon who uses a prosthetic lower limb after an accident, operating with standing aids and modified footwear.

- An ENT surgeon with a hearing impairment using high‑end digital hearing aids and Bluetooth‑linked stethoscope/mic systems.

- An orthopedic surgeon with a partial upper limb amputation using adapted instruments and OR set‑up to maximize leverage and stability.

No, there isn’t a randomized controlled trial of “disabled surgeon vs non-disabled surgeon complication rates” (and if there were, we’d hit bigger ethical problems than disability). But there is precedent from other safety‑critical fields.

Commercial aviation has pilots with significant disabilities flying passengers safely with accommodations and strict competency standards. There are deaf lawyers arguing in court, blind software engineers writing production code, and paraplegic elite athletes smashing records. When environments and tools change, performance follows.

Surgeons are already using accommodations every day; they’re just not labeled that way:

- Loupes and headlamps for visual enhancement

- Powered staplers instead of hand‑suturing everything

- Robotic consoles that let you operate sitting down with finger movements

- Adjustable OR tables and armboards for ergonomics

All of that is “changing the physical task requirements” to suit human limits. That’s literally what disability accommodations do. The line between “ergonomics” and “accommodation” is mostly paperwork and ego.

So is it possible to be a surgeon with a disability? Yes. It already happens. The real question is more nuanced: which specific tasks are essential, and how can they be done safely, effectively, and reliably with or without adaptation?

When institutions actually ask that question instead of hiding behind vague “must have full use of all four limbs” requirements, the barrier shrinks fast.

Myth #2: “Technical standards are fixed. If you can’t meet them, medicine isn’t for you.”

Technical standards are treated like the Ten Commandments. Carved in stone. Handed down from some mysterious committee in the sky.

They’re not.

They’re written by humans—often decades ago—through the lens of “this is how I did it” rather than “this is what the job fundamentally requires in 2026.”

Many schools still have technical standards that say things like:

- “Must be able to hear a patient at normal speaking volume at 20 feet.”

- “Must be able to perform all motor tasks without assistance.”

- “Must have full visual fields and normal color vision.”

Most of those are lazy surrogates for “must be able to obtain and interpret critical clinical information” and “must be able to safely perform required skills.” That can be done in many ways.

| Aspect | Outdated Standard Example | Modern Standard Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing | Hear a whisper at 6 feet | Perceive and interpret auditory info, with aids if needed |

| Motor function | Perform all procedures without assistance | Perform or direct essential tasks safely, with devices |

| Vision | Normal visual acuity and color vision | Access visual information, with assistive tech if needed |

| Communication | Speak clearly and be readily understood | Communicate effectively, using any reliable modality |

And here’s the legal reality people like to conveniently ignore: under the ADA and Section 504, schools and residency programs must provide reasonable accommodations unless it causes “undue hardship” or fundamentally alters the nature of the program or compromises safety.

That “fundamentally alters” language is thrown around a lot. Usually by someone who hasn’t actually done the work of analyzing the task.

Let’s be precise:

- Reassigning all call because someone has a disability? Probably not reasonable.

- Allowing a resident with limited stamina to have protected brief sitting breaks between cases, or use a stool in the OR? That’s reasonable.

- Exempting someone from learning a core comp entirely in a procedure‑heavy specialty? Probably not reasonable.

- Allowing them to learn it with adaptive tools (robotic platform, modified grips, assistive visualization)? Reasonable.

The bottom line: technical standards are supposed to be updated as medicine, technology, and law evolve. If your school’s “standards” read like they were typed on a typewriter, there’s your real problem.

Myth #3: “Accommodations will lower standards or put patients at risk.”

This one sounds serious, which is why it gets weaponized so often.

There’s no broad evidence that disabled clinicians with accommodations are less safe. What we do have is evidence that:

- Physicians with untreated impairments (including fatigue, burnout, substance use) pose clear risk to patients.

- Systems that block disclosure and accommodations force people to hide disabilities and work without support. That’s where risk shows up.

So if you care about patient safety, you should be pro-accommodation, not anti.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Fear of stigma | 78 |

| Fear of dismissal | 54 |

| Licensing concerns | 49 |

| Lack of trust in program | 62 |

| Not aware of process | 35 |

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has been pretty clear in its guidance: disability and technical standards must be handled in a way that’s individualized and not blanket‑exclusionary. The Federation of State Medical Boards has also been moving away from intrusive “have you ever had a mental health diagnosis?” questions to focusing on current impairment, not history.

Real patient safety problems look like:

- A resident with uncontrolled epilepsy who’s denied accommodations, hides their seizures, and then has one while driving home post‑call.

- A student with severe ADHD who’s refused extra time on NBME exams, fails multiple tests, and spirals into depression.

- A surgeon with progressive vision loss who isn’t given access to magnification/visual aids and silently struggles with fine tasks.

All of these are fixable with reasonable accommodations and honest dialogue. Instead, institutions often respond with, “We can’t make exceptions” as if fairness means treating unequal situations equally.

Standards are outcomes:

Can you safely perform the procedure? Can you make accurate decisions? Can you communicate effectively?

How you get there—adaptive equipment, different positioning, alternative communication tools—is process. The law and the ethics are on the side of adapting the process, not lowering the outcome bar.

Myth #4: “If you disclose a disability, your career is over.”

I’ve heard versions of this standing outside OSCE rooms, in resident workrooms, and at conferences: “Never, ever tell them. They’ll use it against you.”

That fear doesn’t come from nowhere. Disabled docs have been:

- Quietly advised to “consider a non-clinical path”

- Left out of competitive rotations or letters

- Steered away from procedural specialties “for your own good”

But pretending disclosure is always career suicide is as inaccurate as pretending discrimination doesn’t exist.

Here’s what’s actually going on:

- Some programs are legitimately ahead of the curve. They’ve written modern technical standards, have disability officers who understand medicine, and can point you to actual residents and faculty with disabilities. Those programs exist in every region and across big‑name institutions.

- Other programs are 20 years behind. They use vague “professionalism” labels to punish people who ask for basic accommodations. They still treat “having anxiety and seeing a therapist” as a red flag.

The strategy isn’t “never disclose.” It’s “be strategic and informed.”

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Recognize need for support |

| Step 2 | Contact disability office |

| Step 3 | Talk to trusted faculty |

| Step 4 | Formal documentation and plan |

| Step 5 | Silent implementation |

| Step 6 | Program leadership meeting |

| Step 7 | Implemented accommodations |

| Step 8 | Escalate or consider transfer |

| Step 9 | Preclinical or clinical phase |

| Step 10 | Need program-level changes? |

| Step 11 | Supportive or resistant |

A few evidence‑backed realities:

- Students who get legitimate accommodations earlier often perform better and have fewer professionalism “flags” than those who grind themselves into the ground without help.

- Licensing boards (at least in many states now) focus on current impairment, not the presence of a disability or psych history. The American Bar Association led here; medicine is catching up more slowly, but the direction is clear.

- The 2018 AAMC report on disability in medical education explicitly frames disability as a form of diversity that benefits the profession, not a liability to hide.

Does discrimination still happen? Yes. Do some people get punished for disclosing? Yes. I’m not sugarcoating that.

But the quiet truth is this: many disabled physicians who are successful… disclosed at some point. They just did it with documentation, allies, and a plan—often after they’d already proven they could perform.

Myth #5: “Only certain ‘low-acuity’ specialties are realistic with a disability.”

The stereotype goes like this: if you have a disability, you can do psychiatry, maybe pathology, maybe radiology. But not “real” medicine. Definitely not surgery, EM, anesthesia, OB, or interventional fields.

It’s a lazy myth that ignores how ridiculously diverse tasks are within every specialty.

Look at modern practice patterns:

- Anesthesia: From wheelchair users who can do airway management and procedures with modified ergonomics, to anesthesiologists with hearing impairments using visual monitors and amplified audio.

- Emergency medicine: Docs with mobility impairments focusing on high‑acuity resus bays and delegating compressions or certain transports while taking the lead on decision‑making, ultrasound, procedures they can do safely, and overall team coordination.

- Surgery: Robotic and laparoscopic platforms already “disable” the old requirement of standing for hours, leaning over deep fields, and using pure hand strength.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Mobility impairment | 5 |

| Hearing impairment | 5 |

| Vision impairment (partial) | 4 |

| Chronic illness/fatigue | 5 |

| Neurodivergence (ADHD, ASD) | 5 |

(Scale here is not “severity.” It’s number of different specialties where there are documented practicing physicians with that category of disability.)

The more honest framing isn’t:

“Can a disabled person be a surgeon?”

It’s:

“Given this person’s specific abilities, what roles and scopes within which specialties are safe, sustainable, and enjoyable with reasonable accommodations?”

Sometimes the answer will be: this specific dream specialty is not going to be safe or sustainable for you, with current technology and resources. That’s reality. But that happens to non‑disabled people too. (Five‑foot‑two, poor fine motor, faints at blood but wants CT surgery? Also not happening.)

The key difference is whether that decision is made:

- Using specific, individualized, task‑based analysis

- Or through blanket “no disabled people in X specialty” assumptions

Right now, too many gatekeepers default to the latter.

Myth #6: “Disability is a personal issue, not a systems issue.”

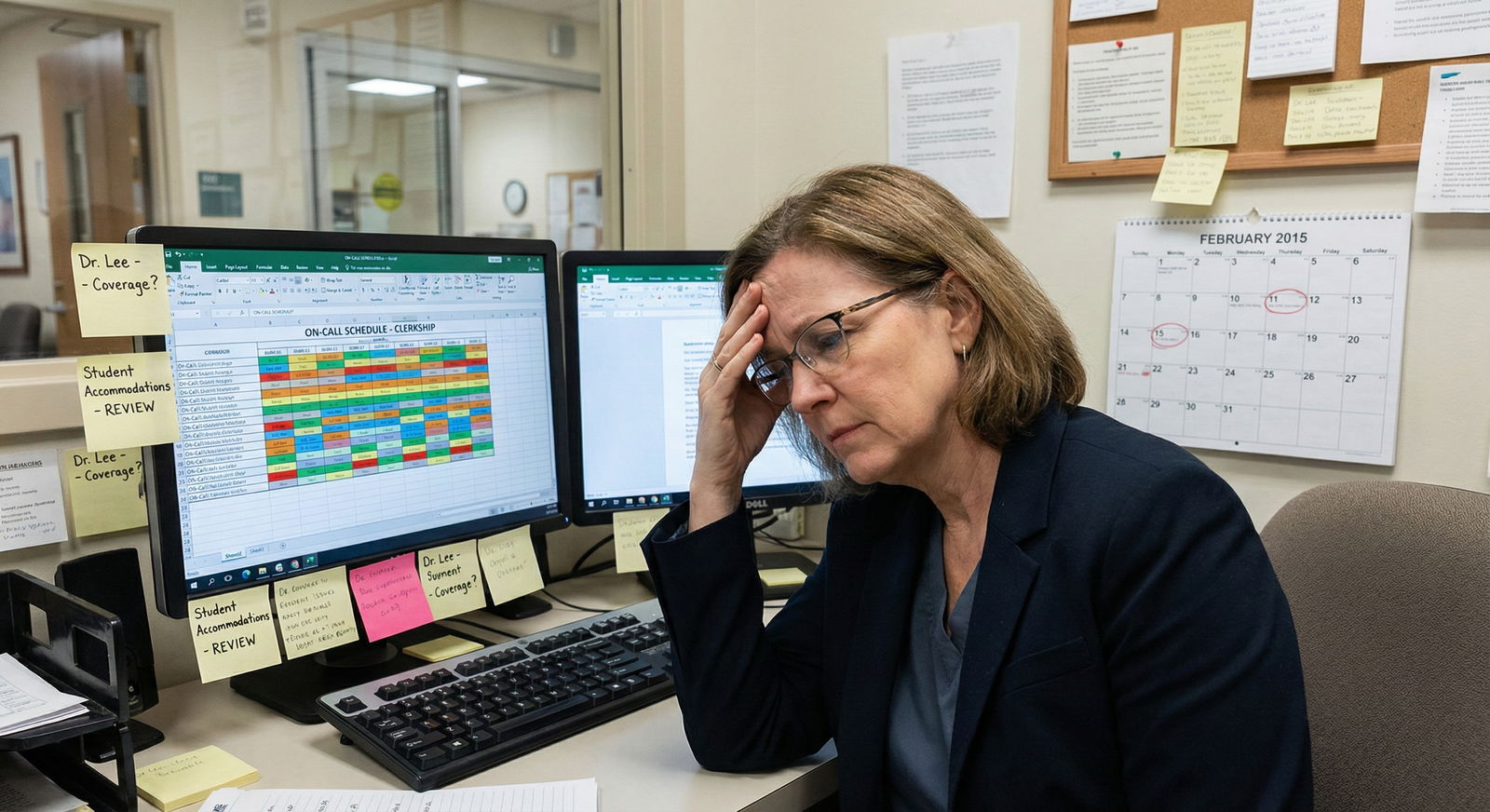

This is the subtle one. The idea that you, the disabled trainee, are the “problem” that needs to be solved privately. Extra grit. Extra resilience. Extra silence.

Meanwhile, the system:

- Designs OSCEs that punish students who use assistive tech

- Schedules 28‑hour calls for people with chronic illnesses and then “wonders” why they flare

- Builds exam interfaces that are nightmares for visual or motor impairments

Here’s the reality: disability in medicine is as much a systems engineering problem as it is a personal one.

Look at what happens when you treat it that way:

- Digital stethoscopes with visual waveforms help hearing‑impaired clinicians… but they also help everyone distinguish subtle murmurs.

- Closed captions and asynchronous lectures for students with processing disorders… also help non‑native speakers and people watching content after long shifts.

- Smarter scheduling and fatigue management for folks with chronic conditions… reduces burnout and errors across the board.

The same way we finally admitted that burnout isn’t fixed with yoga and pizza, we need to admit that disability inclusion isn’t fixed by telling individuals to “advocate for themselves harder.”

If your program boasts about wellness but still has pre‑ADA technical standards and a disability office that’s never seen a hospital floor, that’s not a “you” problem.

The Future: Surgery and Procedural Medicine Are Getting More Accessible, Not Less

If you look forward instead of backwards, the argument that disabled physicians “won’t fit” makes even less sense.

Robotics, telemedicine, augmented reality, and AI‑assisted visualization are exploding. For procedural fields, that means:

- More seated, console‑based procedures instead of physically brutal open cases

- Enhanced visualization and haptics that reduce reliance on raw physical strength or unaided senses

- Remote proctoring and assistance, where a surgeon can guide, intervene, or collaborate across distances

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 2005 | 50 |

| 2010 | 1000 |

| 2015 | 2500 |

| 2020 | 5500 |

| 2025 (proj) | 8000 |

We’re also slowly, finally, reframing disability as a diversity asset:

- Disabled physicians tend to be extremely good at workarounds. That shows up as clinical creativity and system‑level problem solving.

- Patients with disabilities often get better care from clinicians who “get it” and don’t treat their disability as a curiosity or inconvenience.

- Teams that have to think through accommodations get better at explicitly defining tasks and safety thresholds—good for everyone.

So what do you actually do if you’re disabled and want a procedural career?

No fluff. Here’s the pragmatic version:

- Get objective about your abilities and limits. What can you reliably do? For how long? Under what conditions? You need specifics, not vibes.

- Learn the actual tasks in your target specialty. Not the mythology. Talk to residents and attendings about day‑to‑day work, not just “OR time.”

- Involve a disability professional who understands health care. Not just a campus generalist who’s never seen an OR schedule.

- Think in terms of tasks and accommodations, not labels. “Can’t stand for 6 hours straight” is a task‑accommodation problem. So is “needs visual magnification for fine work.”

- Choose programs, not just specialties. Some residencies will fight for you; others will fight you. They’re not interchangeable.

And if you’re faculty or leadership, stop hiding behind “we’re just not sure it’s safe.” Do the work. Define essential tasks, invite legal and disability experts in, and update your dinosaur‑age technical standards.

The Short Version

- “You can’t be a surgeon with a disability” is factually wrong; disabled surgeons and other proceduralists exist and practice safely right now.

- The real barrier isn’t ability; it’s outdated technical standards, institutional fear, and refusal to individualize safety and competency assessments.

- As technology and law move forward, medicine will either adapt to include disabled clinicians—or get left looking archaic while the rest of the world passes it by.