The way most applicants “name-drop” faculty and curricula in letters of intent is lazy and obvious. Admissions committees can smell it in two sentences.

You want to reference specific faculty and curricular features because you have to. This is a letter of intent strategy article, not a vibe essay. But the line between “genuinely engaged” and “I ctrl+F’d ‘research’ on your website” is thin. Let me show you exactly how to walk it.

The Core Problem: You Sound Like a Brochure, Not a Colleague

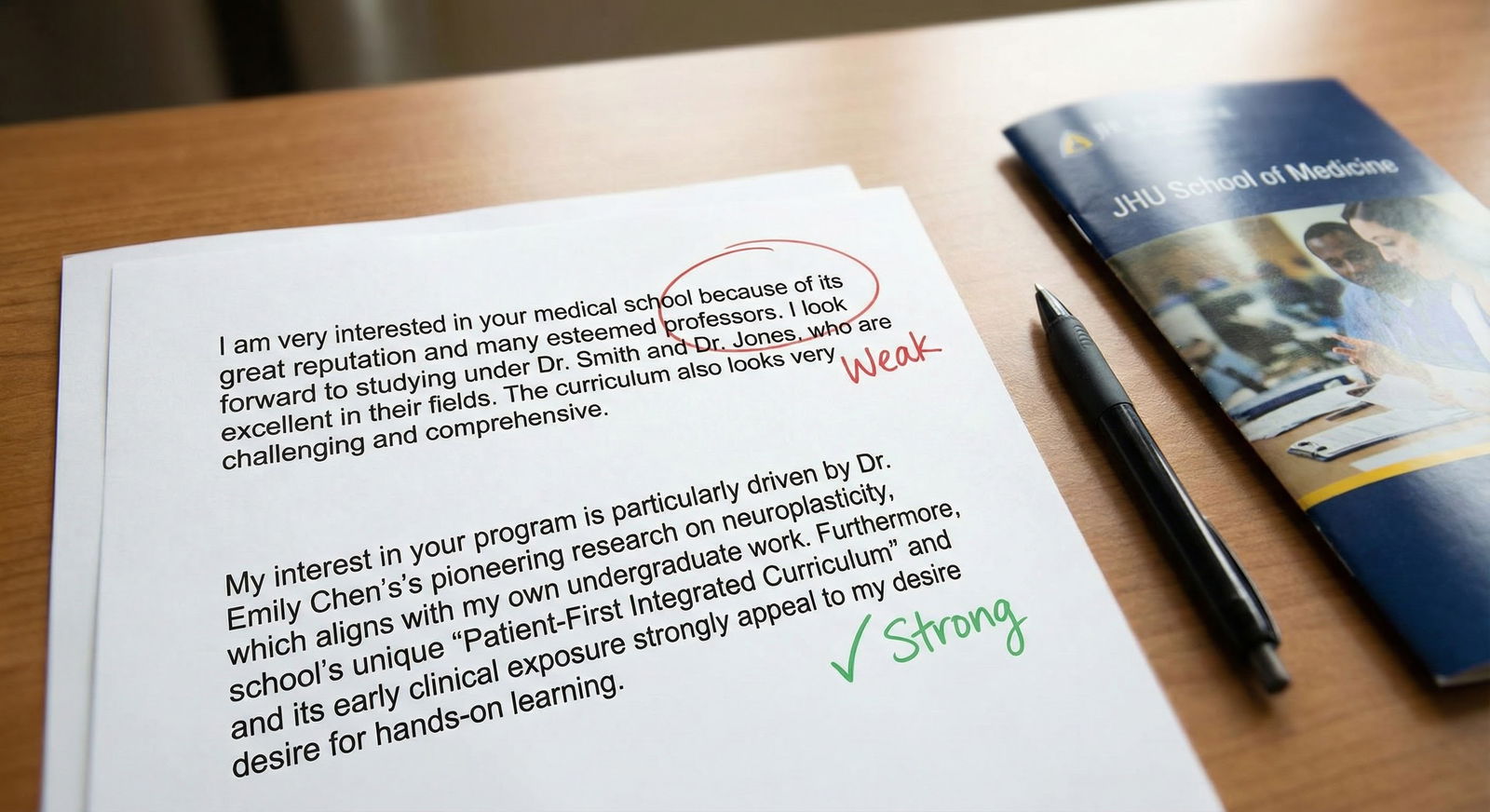

Most letters that try to “customize” look like this:

“I am particularly excited about the opportunity to work with Dr. Smith, whose research on health disparities aligns with my interests. In addition, your integrated, systems-based curriculum and early clinical exposure make your program my top choice.”

You think that sounds fine. On an adcom, it reads as: I skimmed your website 15 minutes before submitting this.

The patterns that make you sound scripted:

- Listing 2–3 faculty and 2–3 curricular buzzwords in one paragraph

- Using phrases like “aligns with my interests” with zero specifics

- Copy-pasting the school’s own language: “longitudinal integrated clerkship,” “innovative spiral curriculum,” “interprofessional education” without any personal link

- No timeline. No plan. Just wishful “I would love to” statements

What a serious reader actually wants:

- Clear, specific connections between your past work and what that faculty member actually does

- Evidence that you understand how the curriculum works, not just its name

- A forward-looking, plausible plan: “Here is how I see myself in your system in Year 1/2/3+”

So the entire game is this: move from flattery + listing → integration + projection.

Step 1: Stop Collecting Names. Start Building a Mini Case File.

Pulling names off a faculty page is the amateur move. You need a micro–case file on 2–3 faculty and 2–3 curricular elements. That is it. Depth beats breadth.

Here is how you do it quickly and properly.

](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_svg/chart-time-allocation-for-strong-letter-of-intent-resear-5491.svg)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Faculty deep dives (2–3 people) | 40 |

| Curriculum and tracks | 25 |

| Program culture and clinical sites | 20 |

| [Proofreading and polishing](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/letter-of-intent-strategy/precision-editing-tightening-lois-to-under-350-words-effectively) | 15 |

A. Faculty: Go One Level Deeper Than Everyone Else

For each potential faculty member:

Google:

FirstName LastName MD site:eduorFirstName LastName MD PhD pdfOpen:

- Their institutional bio

- One recent paper (or abstract) from the last 3–4 years

- Any talk/interview if available (YouTube, Grand Rounds, podcast)

Extract 3 things:

- Actual topic, in your own words

- Methods / setting, if relevant (e.g., EHR-based outcomes, community-based participatory research, mouse model, device trials)

- One thing you can genuinely connect to from your past work or clearly articulated future direction

Bad: “Dr. Lee studies cardiology outcomes.”

Better: “Dr. Lee’s work using EHR-based phenotyping to identify heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction at high risk for readmission.”

Now link:

“I worked with our hospital quality improvement team building an EHR-based alert for high-risk ED discharges; Dr. Lee’s approach is technically different but conceptually similar, and that is the level I want to operate at.”

That kind of sentence signals you actually read what they do.

B. Curriculum: Move Beyond the Tagline

Everyone parrots: “longitudinal integrated curriculum,” “early patient exposure.” You need operational understanding.

Go to:

- MD program → curriculum overview

- Clerkship / LIC / track pages

- Any “Student Handbook” PDF or “Course Catalog”

Look for:

- How the preclinical years are structured: blocks? systems? how many weeks?

- How clinical years are sequenced: traditional blocks vs longitudinal integrated clerkships

- Any distinctive threads: population health, informatics, AI, rural health, advocacy, humanities

- Year-specific programs: scholarly concentration, required QI project, capstone

You are aiming for: “I know how this actually shows up in a student’s week.”

| Type | Weak Reference | Strong Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Preclinical | "systems-based curriculum" | "8-week organ-system blocks with weekly case-based small groups and 1 half-day in clinic" |

| Clinical | "early clinical exposure" | "LIC model with continuity in 3 core specialties over 9 months" |

| Longitudinal thread | "focus on health equity" | "4-year Health Equity Pathway with monthly seminars and required community project" |

You do not need everything. Two or three specific features you can name and use in your narrative is enough.

Step 2: Convert Info Into a Narrative, Not a List

Here is the structural mistake you keep seeing:

“I am excited by Dr. X’s research in Y. I am also interested in Dr. A’s work in B. Your longitudinal curriculum and Health Equity Pathway are also very appealing.”

This is a birthday list, not a letter of intent.

The fix: group everything around 2–3 themes that match (1) your past, and (2) your future goals. Then attach faculty and curriculum to those themes.

Typical themes that actually work:

- Health disparities / population health

- Medical education and curriculum design

- Digital health / AI / informatics

- Surgical innovation and outcomes

- Primary care in underserved or rural settings

- Physician–scientist trajectory in a specific domain (oncology, neuro, etc.)

Example: Health Equity Theme

Instead of:

“I am passionate about health equity. I would be honored to work with Dr. X and participate in your Health Equity Pathway and longitudinal curriculum.”

You write something like:

“My long-term goal is to lead community-partnered interventions that actually change diabetes outcomes for marginalized patients, not just describe the gap. In college I co-led a mobile clinic project that increased HbA1c testing among uninsured Latino patients by 30% over one year, but we struggled with continuity and data tracking.

At [School], I see a clear path to move from enthusiastic volunteer to someone who can design and evaluate serious interventions. Dr. Ana Morales’ community-based participatory research in South LA, especially her 2022 study integrating community health workers into primary care teams, tackles the same continuity problem we hit but with far more rigor. The Population Health and Health Equity track, with its required longitudinal project and faculty mentorship, would give me the structure I was missing before. Layering that with the longitudinal primary care clinic starting in MS1 would let me see the effects of my work over several years in one community.”

Notice what happened:

- Faculty and curriculum are inside the story, not tacked on.

- You demonstrate specific knowledge (2022 study, CHWs, continuity problem) without over-citing.

- You show a concrete before/after: what you did, what was missing, how their system fixes that.

Step 3: Write About Faculty Like a Future Collaborator, Not a Fan

You are not trying to sound like a fan club president. You are trying to sound like a future junior colleague who has done their homework.

The worst lines are the “I would be honored to work with Dr. X, whose groundbreaking research in Y aligns with my interests.” It reads like every single LOI.

Replace that with: problem → what they do → where you plug in.

Weak vs Strong Faculty Mentions

Weak:

“I am particularly excited about the opportunity to work with Dr. Chen, whose research on sepsis outcomes aligns with my interests.”

Strong:

“My research in the MICU has been limited to retrospective chart review, and we constantly hit the frustration of not being able to intervene in real time. Dr. Chen’s work implementing and then studying an early warning system for sepsis on the general medicine wards is exactly the translational step I want to learn. If I am fortunate to train at [School], my goal would be to join Dr. Chen’s group to help adapt that model to the ED observation unit, where I have seen similar missed early decompensations during my scribe work.”

Notice:

- You do not say “groundbreaking” or “aligns with my interests.” You show the alignment.

- You specify where you think your contribution could live (ED obs unit).

- You acknowledge you would be joining their framework, not reinventing it.

A few rules:

- One or two faculty is often enough. Three can work if they clearly share a coherent theme.

- Do not claim you will “definitely” work with them; programs know projects shift. Use “I hope to,” “my goal would be,” “I see myself…”

- Never make it sound like you expect a job already: avoid language like “joining their lab as a key member” or “leading” in MS1.

Step 4: Talk About Curriculum Like Someone Who Read More Than the Landing Page

Committees do not expect you to have memorized the block schedule. But they can tell if you clicked beyond the overview.

The mistake is generic statements:

“Your integrated curriculum, early clinical exposure, and commitment to interprofessional education make your program ideal for me.”

Just noise. Here is how to anchor curriculum in your trajectory.

A. Preclinical: Show How You Learn, Not Just What They Teach

Example of weak:

“Your systems-based integrated curriculum will help me become a better physician.”

No content. Here is a stronger version:

“I learn best when basic science is attached to a real patient. At my home institution, the few case-based sessions we had in MS1 were the ones that stuck. [School]’s 8-week cardiovascular and pulmonary block, with weekly small-group case discussions and integrated ultrasound teaching, fits that learning style. Being in clinic one half-day a week during MS1, seeing patients with the same cardiology preceptor while we cover those organ systems, is exactly how I want to train my clinical reasoning from day one.”

Specific. You do not need 100% accuracy on every detail, but you should be directionally correct. If you are guessing, you have not read enough.

B. Clinical: Show How the Structure Fits Your Goals

This is where LICs, rural longitudinal tracks, or campus options matter. Most students simply rephrase the website.

Bad:

“The longitudinal integrated clerkship will help me form lasting relationships with patients.”

Sure. That is the tagline. But sharpen it:

“During my longitudinal free clinic work, the single most educational moment for me was seeing a patient I had met as a college sophomore return three years later after an ICU admission with new heart failure. I finally saw the arc. The LIC at [School], with 9 months of continuity in internal medicine, surgery, and pediatrics, recreates that arc deliberately. For someone who wants to do primary care in an underserved community, building those relationships while also being accountable for the full spectrum of care is far more valuable than 6-week siloed blocks.”

Now the curriculum is clearly connected to a concrete memory and a future path.

C. Longitudinal Threads and Tracks: Use Them Like Tools, Not Trophies

Every applicant writes “I am excited about your Physician–Scientist pathway / Urban Health track / AI in Medicine certificate.” Most do not say what they would do with it.

For instance:

“The AI in Medicine Distinction is particularly appealing, as I plan to develop AI tools in my future career.”

Empty. Try:

“I built a simple logistic regression model in college to predict 30-day readmission from a dataset of 5,000 discharges. It was a toy project, but it made me realize how much I do not know about model validation, bias, and deployment. The AI in Medicine Distinction at [School], with its two-course sequence on clinical machine learning and required capstone, would give me the structure to move from tinkering to serious, clinically grounded work. My ideal capstone would be to partner with the ED informatics team to test a triage risk score in a pilot workflow, intentionally measuring for differential performance by race and language.”

Again: future-oriented, concrete, and obviously not pulled from a ranking site.

Step 5: Integrate “Future of Medicine” Thoughtfully—Not as Tech Worship

You mentioned Phase: Miscellaneous and Future of Medicine. That is where many letters jump the shark into generic futurism:

“As medicine increasingly moves toward AI and telehealth, your curriculum’s emphasis on innovation will prepare me to practice in the 21st century.”

This is filler. The reader’s eyes glaze over.

If you want to reference “future of medicine” themes (AI, telehealth, value-based care, population health, planetary health), tie them to:

- A problem you already care about

- A specific program element at that school

- A skill set you want to leave with

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| AI / Digital health | 80 |

| Telehealth | 55 |

| Value-based care | 40 |

| Health equity | 90 |

| Climate / planetary health | 20 |

Example done poorly:

“With the rise of AI, your informatics curriculum will prepare me to be a leader in the future of medicine.”

Example done correctly:

“I do not care about AI as a buzzword. I care about the fact that in our ED, non-English-speaking patients routinely wait longer and are more likely to leave without being seen. If algorithms can help triage better, they also have the potential to harden that disparity.

[School] is one of the few places actually teaching students to interrogate these tools. The Clinical Informatics selective and the joint seminar between the School of Medicine and the School of Computer Science on algorithmic bias are exactly where I want to be. Under faculty like Dr. Rivera, who is already working on fairness metrics for ED triage scores, I can see myself learning how to evaluate and implement tools instead of becoming the kind of physician who either blindly trusts them or rejects them outright.”

That is “future of medicine” grounded in real stakes, not buzzword soup.

Step 6: Kill Scripted Language At The Sentence Level

You can do all the research in the world and still sound fake if you fall back on the same tired constructions. Let me be blunt: certain phrases instantly mark your letter as templated.

Here are the worst offenders and what to swap in.

| Scripted Phrase | Stronger Alternative |

|---|---|

| "I am particularly excited about..." | "What draws me most is..." |

| "aligns with my interests" | "extends the work I began in X" |

| "would be honored to work with" | "hope to learn from / contribute to the work of" |

| "innovative curriculum" | Describe the specific innovation in plain terms |

| "cutting-edge research" | Name the actual project / method and why it matters |

And some hard rules:

- Avoid listing more than two “I am excited about…” sentences in a row. Vary the structure.

- Replace abstract adjectives with concrete details. Do not say “robust community engagement”; say “monthly mobile clinics in three neighborhoods plus a required MS2 advocacy project.”

- Stop telling them they are “prestigious,” “renowned,” or “world-class.” They know. It adds nothing.

Try this exercise: after drafting, highlight every adjective in one color and every proper noun (faculty name, program, track) in another. If you see a heavy adjective cluster and a bunch of proper nouns with no verbs and no story, you are listing, not integrating.

Step 7: Structure the Letter So Your “Specifics” Actually Land

Even if you write excellent individual sentences, poor structure can bury them. A strong letter of intent that cites faculty and curriculum without sounding scripted generally follows this arc:

- Opening – Clear commitment and brief restatement of your core direction

- Past → Present – 1–2 paragraphs showing what you have actually done (clinically, academically, in research or service)

- Program Fit – Faculty + Curriculum integrated – 2–3 paragraphs where:

- Each paragraph is built around a theme (e.g., health equity, informatics, primary care)

- Within each, you mention 1–2 faculty and 1–2 curricular features as tools to pursue that theme

- Future Trajectory – 1 paragraph projecting forward: “If I train at [School], here is what the next 5–10 years could look like.”

Here is a stripped-down schematic in flow form:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Opening - Clear Commitment |

| Step 2 | Past Work - Theme 1 |

| Step 3 | Past Work - Theme 2 |

| Step 4 | Program Fit - Faculty and Curriculum for Theme 1 |

| Step 5 | Program Fit - Faculty and Curriculum for Theme 2 |

| Step 6 | Future Trajectory - 5 to 10 year vision |

Notice there is no “Faculty paragraph” and separate “Curriculum paragraph.” That is how you end up sounding like you are checking boxes. Instead, they live together inside your themes.

A Concrete Before-and-After Example

Let me show you how the same ingredients can come out scripted or authentic.

Scripted Version

“I am writing to express my strong interest in [School], which is my top choice for residency. Your program’s innovative curriculum, diverse patient population, and strong research opportunities make it an ideal fit for my interests in internal medicine and health disparities.

I am particularly excited about the opportunity to work with Dr. Lisa Carter, whose groundbreaking research on hypertension in underserved populations aligns with my interests. I would also be honored to work with Dr. James Patel on his research in diabetes management. In medical school, I conducted research on cardiovascular risk factors and presented my work at a regional conference.

Furthermore, your longitudinal curriculum and emphasis on community engagement appeal to me. The Health Equity Track and early continuity clinic experience would allow me to pursue my passion for underserved care. I believe that [School]’s commitment to innovation and the future of medicine will prepare me to be a leader in this field.”

This is what 90% of letters look like. Vague, repetitive, generic.

Rewritten Version Using Principles Above

“[School] is the one place where I can see my interest in chronic disease in underserved communities maturing into serious, community-partnered work. It is my top choice.

My interest in health disparities is not theoretical. For the last two years I have worked on a project at [Home Institution]’s safety-net clinic identifying patients with uncontrolled hypertension who were lost to follow up. We found that 40% of our patients with SBP above 160 had not been seen in over a year. I helped design a pilot in which medical students called 100 of these patients, but we had no framework for addressing the social barriers we uncovered. The result was predictable: many appreciated the call; few actually made it back into clinic.

What I am missing is an environment that treats those barriers as central rather than peripheral. Dr. Lisa Carter’s work at [School], especially her cluster-randomized trial of community health workers embedded in primary care teams for hypertension management, tackles exactly the gap we saw. If I match at [School], my goal would be to join her group and help adapt similar interventions to the Latino population served at your Eastside clinic, building on my Spanish-language outreach experience.

The way your curriculum is structured would let me pursue that work in a sustained way rather than in disconnected blocks. Starting continuity clinic in PGY-1 with a panel drawn largely from the Eastside clinic, while simultaneously participating in the Health Equity Track’s longitudinal project, means I could follow the same patients through the implementation of an intervention, not just help with baseline data collection before graduating. The weekly evening seminars on structural racism in health care would also give me the vocabulary and frameworks that my current training has lacked.

Looking beyond residency, I want to be the kind of internist who splits time between a safety-net primary care clinic and a health system role designing and evaluating community-based interventions. [School] is the environment where I can learn not only to care for individual patients but to rigorously test and scale the ideas that might serve them better.”

Same ingredients: Dr. Carter, Health Equity Track, continuity clinic. Completely different impact. One sounds like a website rehash. The other sounds like a person with a trajectory who has done their homework.

A Quick Sanity Checklist Before You Send

Use this as a final filter. If you cannot answer “yes” to most of these, you are still too close to scripted.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Specific faculty work connected to your past | 85 |

| Curriculum described in how it works, not just named | 80 |

| Themes linking faculty and curriculum together | 70 |

| Concrete future projects described | 65 |

| Scripted adjectives minimized | 90 |

- If I delete all program and faculty names, does the letter still read like it is about me and my trajectory?

- For each faculty member mentioned, did I show I know what they actually do, not just their title?

- For each curricular feature mentioned, did I explain how I would use it and why it matters for my learning style or goals?

- Did I avoid stacking more than 2–3 proper nouns (program names, tracks, titles) in a single sentence?

- Did I kill phrases like “aligns with my interests,” “innovative curriculum,” “cutting-edge research,” and replace them with real descriptions?

- Would a faculty member at that institution read this and think, “Yes, this person understands how we work,” rather than, “Nice brochure copy”?

If you hit those, you are ahead of the majority of applicants.

The Three Takeaways That Actually Matter

- Stop listing; start integrating. Faculty and curriculum should live inside your themes and trajectory, not as separate bullet points of flattery.

- Be concrete and operational. Show that you understand what specific people do and how specific curricular structures function, then plug yourself into that machinery.

- Kill the template language. The second you write “aligns with my interests” or “innovative curriculum,” you are drifting into brochure territory. Replace adjectives and buzzwords with details, plans, and real problems you want to work on.