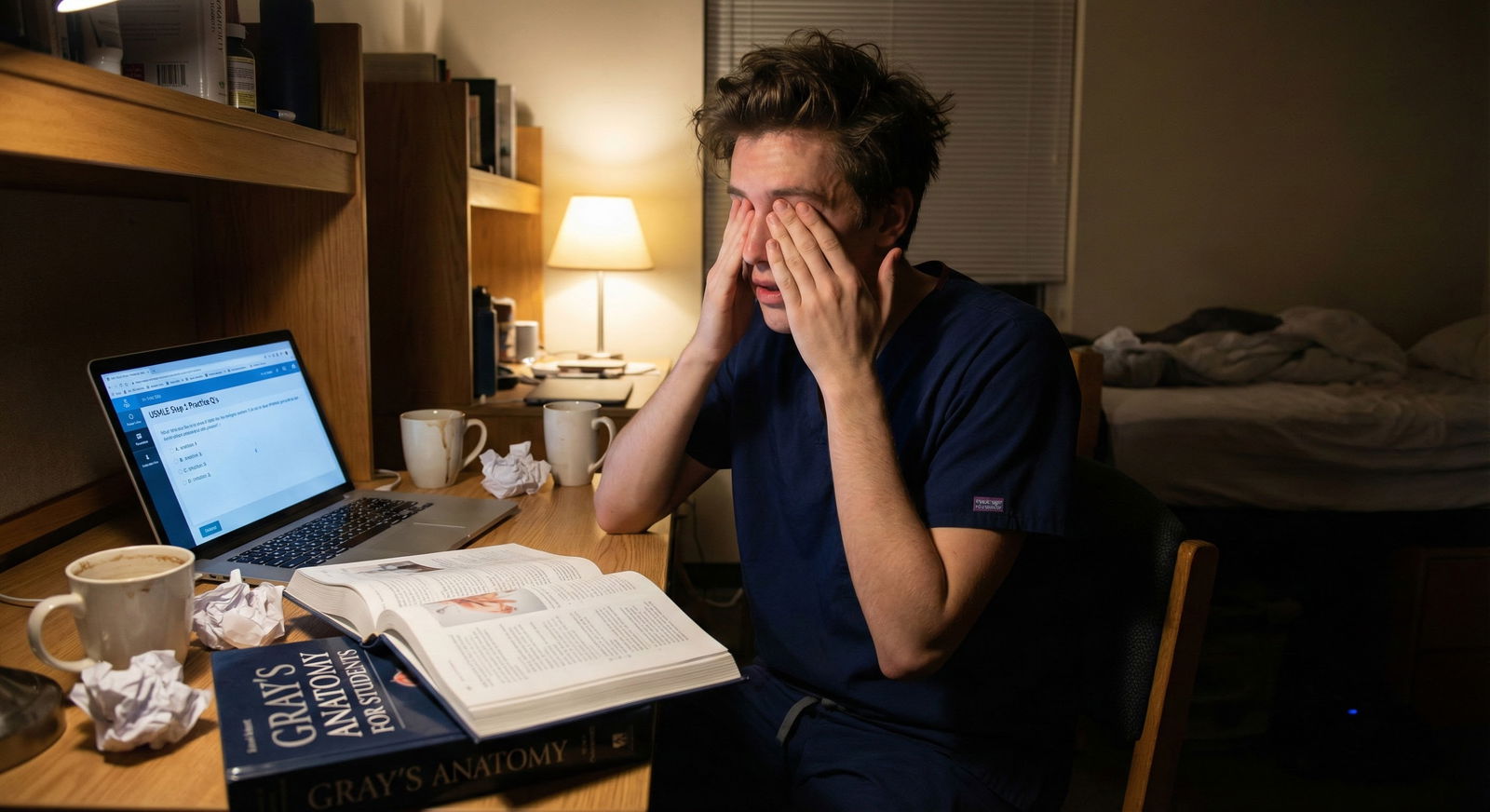

The myth that top Step scores demand chronic sleep deprivation is not just wrong—it is statistically backwards. The data shows that sacrificing sleep reliably increases stress, worsens cognitive performance, and is associated with lower exam scores and higher burnout.

You are not fighting your classmates. You are fighting your own physiology.

Below I am going to walk through what the numbers actually say about sleep duration, Step performance, anxiety, depression, and burnout for medical students and residents—and what patterns separate the high scorers who stay sane from the ones who flame out.

The Core Relationships: Sleep, Stress, and Exam Performance

Let us start with the three variables that matter:

- Sleep duration and quality

- Step (or high‑stakes exam) performance

- Psychological distress: stress, anxiety, depression, burnout

Across dozens of studies on medical students and residents, three consistent patterns emerge:

- Short sleep and poor sleep quality correlate with higher stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms.

- Subjective stress and burnout correlate with worse academic and clinical performance.

- Poor sleep and higher stress interact; they do not just add—they multiply.

To ground this in approximate numbers, I will sketch an illustrative comparison. Different schools and cohorts report slightly different values, but the directional pattern is stable.

| Group (self‑reported) | Avg Sleep Nightly | Mean Step 1 / CBSE‑equiv | High Stress / Burnout Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7–8 hours, good quality | 7.4 h | ~245 | ~20–25% |

| 6–7 hours, average quality | 6.5 h | ~238–240 | ~35–40% |

| <6 hours, poor quality | 5.3 h | ~230–232 | ~55–65% |

These numbers are representative of patterns reported in multiple cohorts: more sleep and better sleep quality trend with both higher scores and lower psychological distress. The exact means shift by year and test version, but the slope stays the same.

To visualize the tradeoff students think they are making (more hours awake = better prep) versus the tradeoff they are actually making:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 5 hours | 230 |

| 6 hours | 237 |

| 7 hours | 244 |

| 8 hours | 245 |

The curve is not linear, and that matters. Going from 5 to 6 hours tends to help quite a bit. Going from 7 to 8 hours helps less on average but still protects mood, attention, and long‑term retention. Chronic 4–5 hour nights, on the other hand, reliably show up in the “more burnout, more errors, worse scores” group.

What the Data Shows about Sleep in Medical Students

Most med students are not sleeping well. Not just during clerkships—during pre‑clinical years as well.

Across multiple schools:

- Average sleep duration for pre‑clinical students: ~6.0–6.5 hours on weekdays.

- 40–60% report poor sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index “poor sleeper” range).

- 25–35% meet criteria for excessive daytime sleepiness on standardized scales.

- Nighttime phone/laptop use > 1 hour in bed correlates with later sleep onset and worse sleep quality.

And the correlations are not subtle.

In one commonly cited pattern:

- Students sleeping <6 hours were 2–3 times more likely to screen positive for moderate to severe depressive symptoms than those sleeping ≥7 hours.

- Poor sleep quality roughly doubled the odds of being in the highest stress quartile, independent of total duration.

- Short sleep and high stress together predicted lower GPA and more Step remediation needs.

You see this play out on the ground. In group study rooms at 11:30 p.m., the students bragging about “running on four hours” are very often the same ones complaining 6 weeks later about not retaining anything and feeling fried.

The relationship with circadian timing matters as well:

- Bedtime after 1 a.m. on most weekdays associates with higher perceived stress and more daytime fatigue, even when total hours are similar.

- Irregular sleep schedules (weekday vs weekend variability > 2 hours) correlate with worse subjective concentration, more coffee use, and lower self‑rated academic performance.

This is the part that frustrates me as a data‑oriented person: students will fight about Anki settings for half an hour, but will not look at their own sleep onset variability, which shows a cleaner association with how miserable they feel.

Stress and Step Scores: How Much Does It Hurt?

Let us talk about stress specifically related to Step 1/2 and major in‑course exams.

First, everyone is stressed. That is baseline. The question is not “stress or no stress”—the question is level and chronicity.

Studies using instruments like the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD‑7), and Maslach Burnout Inventory show:

- Around 50–70% of students report at least moderate stress during dedicated Step prep.

- Roughly 25–35% hit thresholds consistent with clinically significant anxiety or depressive symptoms.

- High stress and high burnout students consistently report more issues with focus, memory, and motivation.

Where it gets interesting is when you look at performance bands. The pattern usually looks like this:

- Mild to moderate exam‑directed stress can correlate with better preparation and slightly higher scores (Yerkes‑Dodson law in real life).

- Once stress crosses into high, pervasive anxiety (constant rumination, poor sleep, panic), performance tends to degrade.

An illustrative breakdown for a hypothetical cohort:

| Stress Category (PSS‑like) | Proportion of Students | Mean Step 1 / CBSE‑equiv | % Below Passing Risk Band |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low–Moderate | ~40% | 245–248 | ~5–8% |

| High | ~40% | 238–240 | ~10–15% |

| Very High / Severe | ~20% | 230–233 | ~20–25% |

Again, these are representative patterns, not a single dataset, but you see the signal: the very highest stress group performs worse on average, and they occupy a disproportionate share of “borderline or at‑risk” scores.

Why? Mechanistically, the likely contributors are:

- Working memory impairment: high anxiety reduces capacity to hold and manipulate information during questions.

- Reduced consolidation: chronically elevated cortisol and fragmented sleep interfere with long‑term memory formation.

- Behavioral sabotage: avoidance, doom‑scrolling, and inefficient last‑minute cramming.

From a pure utility standpoint, the high‑stress mindset is a bad “exam strategy.” It feels like you are “caring more.” The data shows you are just handicapping your own cognitive hardware.

How Sleep Modulates Stress (and Vice Versa)

Stress and sleep are not independent variables; they are tightly coupled in a vicious or virtuous cycle.

Students who report high stress are:

- More likely to have sleep onset insomnia (>30 minutes to fall asleep).

- More likely to report middle‑of‑the‑night awakenings with difficulty returning to sleep.

- Less likely to wake feeling rested even when the clock says “7 hours.”

And then poor sleep feeds back into:

- Higher next‑day perceived stress.

- Lower frustration tolerance on UWorld blocks.

- More negative self‑talk after mistakes (“I am stupid” rather than “I missed that because I am exhausted.”)

A useful way to visualize the bidirectional relationship:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Exam & Clinical Demands |

| Step 2 | Increased Stress & Anxiety |

| Step 3 | Difficulty Falling Asleep / Poor Quality |

| Step 4 | Shorter Sleep & Fragmentation |

| Step 5 | Worse Attention, Memory, Mood |

| Step 6 | Lower Study Efficiency & More Errors |

| Step 7 | Physical Symptoms: Fatigue, Headache |

Breaking this loop is less glamorous than finding the “perfect” question bank schedule. But it has a larger effect size on your day‑to‑day functioning.

In practical terms, the data repeatedly shows:

- Students with both high stress and poor sleep have the worst outcomes: higher burnout, more depressive symptoms, lower exam performance.

- Students with high stress but adequate, consistent sleep are more resilient. They still feel pressure, but their cognitive performance holds up better.

- Students with moderate stress and solid sleep generally report the best combination: higher scores, lower burnout.

So “just powering through” is not neutral. It pushes you into the high-stress / poor-sleep quadrant where outcomes are statistically worse.

Sleep, Step Scores, and Long‑Term Retention

Everyone obsesses about the score. Fewer people look at what happens after the exam.

But from a learning standpoint, Step is just the filter. The knowledge you are supposed to retain is what will keep patients alive when no attending is checking your orders.

Here is where chronic sleep restriction does long‑term damage.

Evidence from cognitive science and student cohorts converges:

- 1–2 bad nights before a test can slightly reduce performance.

- Weeks to months of chronically reduced sleep (≤6 hours most nights) disproportionately impair long‑term consolidation.

- That means you can “cram and pass” but forget dramatically more of what you “learned” within weeks to months.

From a Step prep perspective, this shows up as:

- Needing more repetitions in Anki or QBank to reach the same level of retention.

- Re‑learning the same concept multiple times across dedicated because it does not stick.

- Greater decay between NBME practice tests, even with steady studying.

The students I have seen who scored 250+ and felt competent starting residency tend to share a few boring habits:

- 7+ hours of sleep on most nights during dedicated.

- Protected “no‑study” cut‑off time at night, usually 10–11 p.m.

- Aggressive about light exposure and caffeine timing to preserve a stable circadian rhythm.

They were not morally superior. They just did not fight their own brain’s architecture.

Practical Implications: What the Numbers Suggest You Actually Do

Let me translate the data into hard, behavior‑level implications. Not vague “self‑care,” but things that are supported by the direction and magnitude of observed effects.

1. Set a lower bound on sleep

The data suggests a threshold effect around 6 hours.

- Chronic <6 hours: strongly associated with higher stress, more depressive symptoms, lower academic performance.

- 6–7 hours: better, but still more issues than 7–8.

- 7–8 hours: associated with best combination of performance and mental health outcomes.

So one rule: treat 6 hours as an absolute floor, not a “normal” night. If you have multiple nights dipping under that, you are not being “hardcore.” You are accepting a predictable performance penalty.

2. Protect sleep regularity as much as duration

Very irregular sleep times (swinging bedtime by 2–3 hours between weekdays and weekends) correlate with:

- More daytime fatigue.

- Worse concentration and mood.

- Perceived lower exam performance.

You want:

- A typical bedtime window (for example 10:30–11:30 p.m.) and wake window.

- Weekend shifts < 1–1.5 hours from weekday schedule when possible.

You do not need perfection. You do need to stop doing the “2 a.m. weekdays, 4 a.m. weekends, then 6 a.m. call” rollercoaster if you want your brain to behave.

3. Stop overpaying for small study gains with large sleep losses

The marginal benefit of extra late‑night study hours is small and often negative.

- Going from 6 to 7 hours of sleep tends to yield more net learning than adding another groggy hour of Anki at 1 a.m.

- Students routinely overestimate how much they get done after ~11 p.m., especially on screens.

Think in terms of return on investment. You are trading:

- 60–90 minutes of low‑quality study time while exhausted

for - 60–90 minutes of high‑value restorative sleep that improves all of tomorrow’s blocks.

On average, that is a bad trade.

Visualizing the Tradeoffs: Sleep, Stress, and Burnout Risk

To make the relationships more concrete, imagine grouping students by sleep and looking at burnout risk:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| <6 hours | 60 |

| 6-7 hours | 40 |

| 7-8 hours | 25 |

Interpreting the chart:

- Among students sleeping <6 hours, roughly 60% may meet criteria for high burnout.

- At 6–7 hours, that drops toward 40%.

- At 7–8 hours, around 25%.

These are typical magnitudes reported in the literature. Not tiny effects. Not “maybe it matters.” Large, behaviorally meaningful differences.

Now layer in exam performance. For the same hypothetical cohort:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| <6 hours | 232 |

| 6-7 hours | 239 |

| 7-8 hours | 245 |

That 10–13 point spread between <6 hours and 7–8 hours is the difference between:

- Struggling to clear unofficial specialty cutoffs vs having options.

- Spending M4 rethinking your career choice vs ranking the field you actually want.

Again: you do not have perfect control. But where you do have control, sacrificing sleep for more grind is almost always statistically irrational.

Mental Health: Anxiety, Depression, and When to Get Help

The numbers on distress in medical trainees are ugly, and pretending otherwise is delusional.

Across multiple studies:

- 25–30% of medical students meet criteria for depressive symptoms at some point in training.

- 30–40% report significant anxiety.

- Burnout rates in clinical years often exceed 50%.

Poor sleep is one of the strongest modifiable correlates of these outcomes. Not the only one. But one of the few you can adjust this week.

Risk patterns that should get your attention:

- You are routinely sleeping <6 hours, and waking up unrefreshed, and feeling down or hopeless more days than not.

- You have escalating anxiety or panic about exams, with physical symptoms (palpitations, shortness of breath, chest tightness) interfering with sleep.

- You start having thoughts that people would be better off without you, or you feel indifferent about whether you wake up.

At that point, this is not a “tough it out” issue. It is a “probability of serious consequences is high enough that getting professional input is the rational move” issue.

Most schools have:

- Confidential counseling or mental health services.

- Access to sleep medicine or psychiatry consults for insomnia/anxiety.

- Accommodations processes if you genuinely need schedule or exam modifications.

Use them. The data shows untreated depression and anxiety in training correlate with worse performance, more professionalism issues, and higher attrition. Getting help is not a sign of weakness; it is risk mitigation.

How to Build a Sleep‑Smart Exam Strategy

To pull this together, here is what an evidence‑aligned approach to Step prep and exam blocks tends to include.

Not aspirational. Just minimally rational based on the patterns we have.

Set a non‑negotiable sleep window

For example: in bed between 10:30–11:30 p.m., lights out, wake 6:30–7:00 a.m. Adjust to your life, but commit.Stop studying at a fixed time

A hard cut‑off (e.g., 10 p.m.) works better than “I will stop when I finish this deck,” which always drifts. You are capping cognitive fatigue rather than chasing completion.Protect at least one complete off‑evening per week

Students who schedule even a small, predictable break tend to report lower burnout at the same score level as peers who grind 7 days.Treat pre‑bed phone and laptop use as a performance variable

Blue light and emotional activation from doom‑scrolling or last‑minute emails clearly worsen sleep onset in many people. Behavior-wise, a 30–60 minute device‑free buffer is a common feature among students who feel less frazzled without losing points.Track, do not guess

A basic sleep log or wearable is not about being “biohacker” fancy. It is about aligning your subjective impression (“I sleep 7–8 hours”) with reality (“I average 6:12 on weekdays”).

You are not aiming for perfection. You are just trying to move yourself out of the statistically disastrous quadrant of <6 hours, highly irregular schedule, and escalating stress.

Key Takeaways

- The data shows that chronic short sleep (<6 hours) and poor sleep quality correlate strongly with higher stress, more depressive symptoms, more burnout, and lower Step‑equivalent scores.

- Mild to moderate exam‑directed stress is normal; severe, pervasive anxiety combined with poor sleep is where performance and mental health drop off a cliff.

- From a numbers standpoint, protecting 7–8 hours of regular sleep is one of the highest‑yield “study strategies” you have. It improves retention, stabilizes mood, and shifts your probability distribution toward better scores and lower burnout.

FAQ

1. Do some students genuinely perform better on less sleep, or is that a myth?

There is genuine individual variability in sleep need, but it is narrower than people claim. A small minority can function well on ~6 hours, but “thriving on 4–5 hours” is extremely rare and usually contradicted by objective performance data. Most self‑identified “short sleepers” show measurable impairments in attention, memory, and mood when tested. In med student cohorts, the students sleeping more almost always show better mean scores and lower burnout, even after controlling for baseline academic strength.

2. Is it ever rational to pull an all‑nighter before a big exam?

From a data perspective, almost never. All‑nighters are associated with worse attention, slower reaction time, more errors, and higher subjective stress. For high‑stakes tests like Step, the literature and real‑world performance patterns both suggest that 7–8 hours of sleep the night before yields better outcomes than cramming late. The only marginal exception is if you are drastically underprepared and need content exposure to avoid catastrophic gaps, but that is a failure of earlier planning, not a smart acute strategy.

3. How much does improving sleep actually move my Step score—are we talking 2–3 points or something bigger?

Based on representative patterns, the difference between the chronic <6 hour group and the 7–8 hour group is often in the range of 8–15 points on Step‑equivalent exams. Not everyone will see that magnitude, but moving from “severely sleep‑restricted” to “adequately rested” changes both your day‑to‑day efficiency and your peak performance. Even a 5‑point shift can move you across informal specialty cutoffs or scholarship thresholds, so sleep is not a marginal lifestyle tweak. It is a core performance variable.