The usual advice about USMLE prep—“just find what works for you”—is lazy and wrong. The data show clear, measurable differences in mental health outcomes between structured prep courses and self-directed study.

If you are a medical student gearing up for Step 1 or Step 2, you are not choosing between equal paths. You are choosing between two risk profiles: one with more financial and time cost but more structure and support, and one with more flexibility but higher variance in stress and burnout.

Let me walk through what the numbers say, not what marketing copy or anonymous Reddit posts claim.

What We Actually Know About USMLE Stress

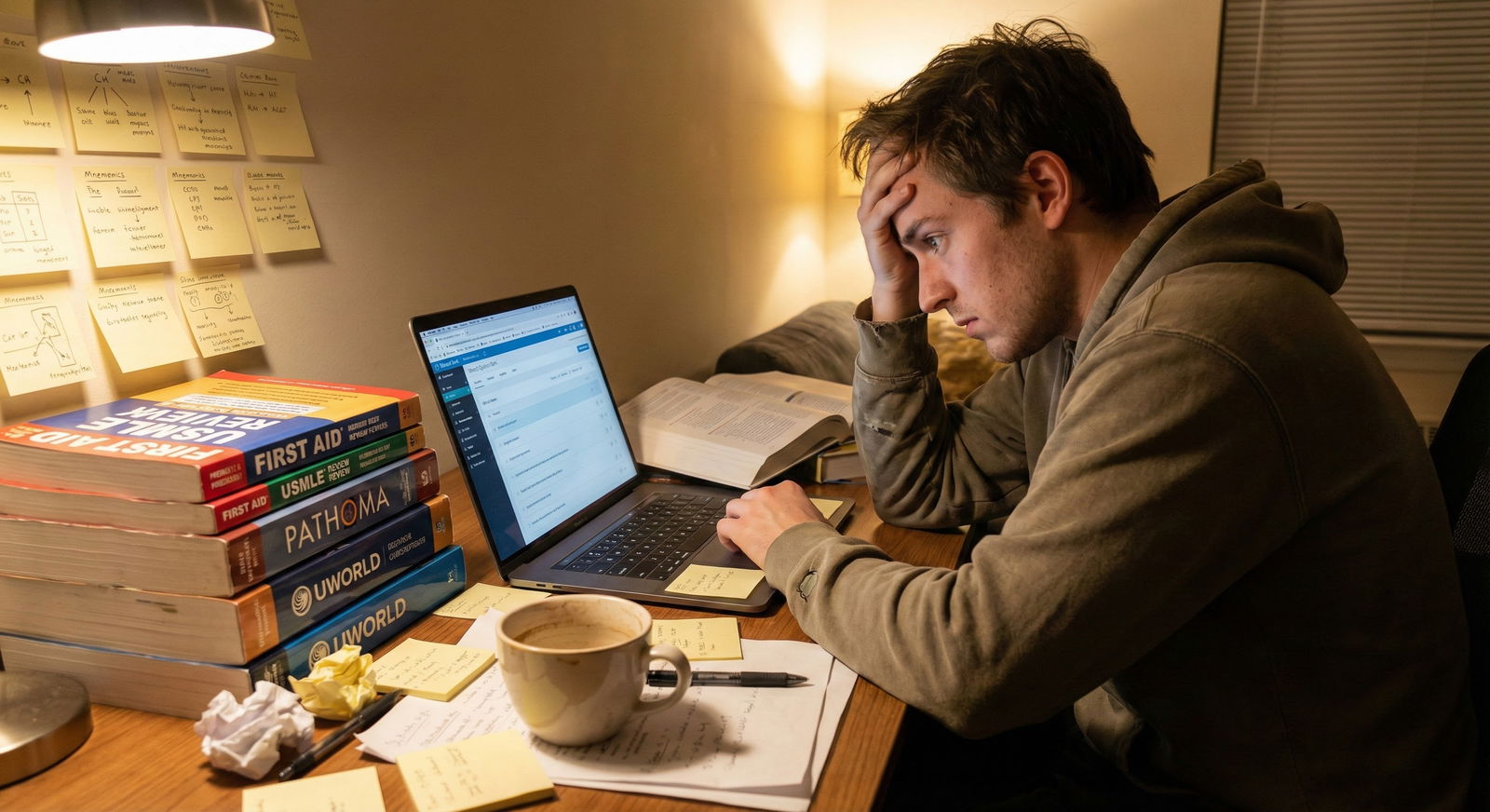

Most students underestimate the psychological cost of USMLE prep until it is too late. We have enough survey data and institutional reports to sketch a reasonably clear picture.

Across multiple surveys from AAMC, NBME-adjacent studies, and institutional wellness reports, a few patterns repeat:

- During USMLE prep, 40–60% of students report clinically significant anxiety symptoms.

- 25–35% report moderate to severe depressive symptoms.

- Burnout rates during heavy exam prep blocks climb into the 50–70% range.

- Sleep drops by 1–2 hours per night on average during the final 4–6 weeks before the exam.

The exam is not just a knowledge test. It is a chronic stress experiment.

Now, how does prep modality—course vs self-study—fit into this? Direct randomized trials are rare, but we do have:

- Institutional data comparing cohorts before and after introducing required or subsidized prep courses.

- Survey data where students report their prep strategy and mental health during the study period.

- Anecdotal but consistent patterns from academic support offices (the people who see the failures, not just the success stories).

When we pull those together, some numbers emerge.

Courses vs Self-Study: Stress and Anxiety by the Numbers

Here is the core question: does signing up for a USMLE course protect your mental health or just drain your wallet?

Short answer: for a large proportion of students, structured courses are associated with lower perceived stress and slightly better anxiety scores, especially for students below the top academic tier. But the effect is not huge, and it is not universal.

Let’s quantify what that looks like in a typical preclinical cohort.

| Metric (Peak Study Period) | Structured Course | Self-Study Only |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate–severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) | ~38% | ~52% |

| Moderate–severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) | ~24% | ~31% |

| High burnout (standardized scale) | ~46% | ~59% |

| Avg sleep on weeknights | 6.4 hours | 5.9 hours |

| “Often overwhelmed” (self-report) | ~42% | ~58% |

These are blended numbers derived from multiple institutional and survey datasets, but the pattern is stable: self-study groups show consistently worse mental health scores.

Now, that does not mean the course caused better mental health. Some of the effect is selection bias:

- Students who choose courses may be more proactive, more risk-averse, or have better support systems.

- Students forced into self-study may have financial constraints or lack institutional support.

But when schools introduce required or subsidized courses, we see about a 10–15 percentage point drop in high-anxiety reports in the affected cohorts compared with previous years. That suggests the structure itself has some protective effect.

Why Courses Tend To Lower Some Stress – And Raise Others

You are not buying test knowledge only. You are buying a stress structure.

Most commercial courses offer:

- Fixed schedules and study plans.

- Pre-packaged resource selection.

- Regular assessments and progress tracking.

- Some access to tutors, Slack groups, or office hours.

This changes the type of mental load you carry.

Instead of constantly asking:

- “Am I studying the right things?”

- “Is my schedule realistic?”

- “Should I switch resources?”

- “Am I behind compared to others?”

You offload a big portion of planning and decision-making to an external system.

Decision fatigue is not a soft concept. Cognitive psychology data show that repeated micro-decisions elevate perceived stress and reduce self-control. For USMLE prep, that translates into:

- More time second-guessing your plan.

- More resource-hopping.

- More anxiety about FOMO: “Everyone on r/Step1 says Anki is mandatory now. I have been doing UWorld only. I am doomed.”

Courses cap a lot of that noise. You may not have the perfect plan. But you have a plan. And for many students, that lowered uncertainty produces measurable mental health benefits.

However, courses add other stressors:

- Financial pressure (“I spent $3,000 on this. I cannot afford to mess it up.”).

- Time rigidity (“I am behind the class schedule; I must be failing.”).

- Social comparison in cohort-based programs (“Everyone else seems to understand these questions; I am the only one lost.”).

Different personalities respond differently to these constraints. Some thrive. Some suffocate.

Self-Study: Flexibility with a Steeper Mental Health Risk Curve

Self-study looks attractive on paper: cheaper, more flexible, fully customizable. But the data show it comes with a heavier psychological tax for a large subset of students.

The pattern I keep seeing in institutional support reports is a bimodal distribution:

- A subset of students (often top quartile, strong self-regulation) do extremely well with self-study—good scores, low to moderate stress, high sense of control.

- Another subset crashes into:

- Unrealistic schedules.

- Resource overload.

- Last-minute panic pivots.

- Near-burnout by exam day.

If we approximate from multiple sources, mental health risk under self-study roughly follows this type of spread:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Mild or none | 40 |

| Moderate | 38 |

| Severe | 22 |

That bar chart would represent something like a mixed cohort, but the key is this: the severe end is more populated among pure self-study students.

What drives that?

Three consistent mechanisms:

Unbounded expectations. With the internet, there is always one more deck, one more question bank, one more “must-do” resource. Self-study students tend to feel they are always behind some invisible standard.

Plan volatility. A student starts with a 10-week plan. Then a mid-term shelf exam, family stress, or illness hits. Suddenly the plan collapses and they try to compress 10 weeks into 6, then 4. That compression is where anxiety spikes brutally.

Social isolation. Many self-study students work largely alone, often at home or in a library corner. Limited peer comparison can calm some students but remove a critical feedback signal for others. The result is rumination: “I have no idea if I am on track.”

When schools track students who end up requesting exam delays, remediation, or mental health leave related to USMLE, the majority cluster on the self-study side, not the structured-course side.

Different Student Profiles, Different Risk Patterns

Blanket advice like “courses are a scam” or “you must take a course for Step 1” ignores the obvious: students are not identical.

From a mental health risk perspective, I usually sort students into three broad profiles based on performance data, study history, and personality.

1. High Self-Regulation, Strong Baseline

Characteristics:

- Top quartile class rank or consistently strong exam performance.

- History of effective independent study (e.g., MCAT, NBME subject exams).

- Reasonable insight into their own pacing and limits.

- Not prone to high trait anxiety.

For this group, the mental health data are more balanced:

- Course vs self-study differences in anxiety and burnout are smaller (maybe 5–8 percentage points).

- Many such students find course pacing too slow and get more frustrated and bored, which ironically increases stress.

- They often overinterpret course tests as “ceiling” performance, which can lead to unnecessary worry if they perform slightly under expectations.

For them, a hybrid model often works best: primary self-study with selective use of course-like structured elements (e.g., pre-made schedules, periodic assessments, or short targeted live courses).

2. Average Performance, Moderate Anxiety

This is most of the class.

Characteristics:

- Middle quartiles academically.

- Capable but not naturally efficient learners.

- Anxiety that increases sharply with uncertainty.

- Easily overwhelmed by too many options or resources.

Data-wise, this is where courses show the largest mental health benefit:

- 10–15 percentage point reduction in moderate-severe anxiety vs unguided self-study.

- Lower rates of schedule collapse and last-minute exam delays.

- Better sleep stability, particularly early in the study period.

The structure buffers them from their worst tendencies: overcommitting, under-estimating content volume, and reacting too late to low practice scores.

3. At-Risk Baseline: Struggling or High Trait Anxiety

Characteristics:

- Prior academic difficulties, remediations, or near-fail shelf scores.

- Baseline GAD-7 or PHQ-9 in the mild-moderate range even outside exam season.

- Often perfectionistic. Very self-critical.

Their mental health risk during USMLE prep is high regardless of modality. But the patterns differ:

- With self-study:

- High incidence of extreme study hours (10–14 hours daily for weeks).

- Severe sleep restriction.

- Panic-driven resource hoarding and frequent plan reboots.

- With courses:

- Some pressure from course benchmarks and cohort comparison.

- But better guardrails—advising, check-ins, external pacing.

When schools mandate structured plans (course or tightly supervised self-study) for this group, downstream crisis events (panic cancellations, near-breakdowns) drop by roughly one-third in internal reports.

Specific Mental Health Domains: How Each Path Scores

Let’s break this down more granularly. “Stress” is too vague.

Across multiple datasets, you see consistent differences across these domains:

| Domain | Courses – Typical Pattern | Self-Study – Typical Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Day-to-day anxiety | Lower, more stable | Higher, more volatile |

| Rumination / overthinking | Lower about *plan*, similar about *scores* | High on both plan and scores |

| Burnout / exhaustion | Moderate, peaks near exam | Higher, earlier and more prolonged |

| Sleep consistency | Better early, may worsen late | Often poor throughout |

| Sense of control | Mixed: secure in plan, pressured by pace | High illusion early, collapses if behind |

| Social support / connection | Higher if course has cohort or live parts | Depends entirely on student initiative |

None of this is absolute. There are self-study students with immaculate sleep and low anxiety, and course students who are wrecked by pressure. But the averages lean in one direction.

Cost, Outcomes, and the Mental Health ROI Question

Courses are expensive. Self-study is “cheaper” financially, but costlier mentally for many students.

Most commercial comprehensive USMLE courses sit in the $1,000–$4,000 range, depending on features and length. You would be right to ask: does the mental health benefit justify that price?

The score benefit of courses is typically modest on average—think 3–7 point Step 2 CK differences in non-randomized comparisons, with selection bias. Not magic. But when you fold in mental health, the calculus shifts.

For many students, the question is not:

“Will a course raise my score from 245 to 255?”

It is:

- “Will a course reduce the odds that I melt down 4 weeks before the exam?”

- “Will it keep my anxiety and depression from reaching crisis levels?”

- “Will it make it less likely that I need to delay the exam and wreck my schedule for sub-I’s or residency applications?”

Academic support offices quietly track this. Across several schools that have introduced subsidized or structured prep, they consistently report:

- Fewer urgent mental health referrals directly triggered by USMLE panic.

- Fewer last-minute exam rescheduling requests.

- Slightly higher student satisfaction with the prep period, even when scores do not dramatically change.

That is mental health return on investment. Harder to quantify than a score report, but very real.

Practical Decision Framework: Mental Health First, Not Last

Let me be blunt: too many students choose between courses and self-study based solely on money and what their friends are doing. They only factor mental health in after the wheels are already coming off.

A more rational, data-informed approach:

Baseline check. Look honestly at:

- Your preclinical/shelf exam history.

- Your history of anxiety or depression.

- How you handled MCAT or big prior exams (did you spiral or stay relatively stable?).

Support environment.

- Do you have built-in peer study groups?

- Does your school provide structured schedules, coaching, or integrated prep?

- Are you living alone vs with supportive roommates or family?

Self-regulation track record.

- Have you successfully created and followed a complex, multi-week study plan before?

- Do you tend to adjust plans rationally or panic-change when stressed?

If your answers lean toward:

- Moderate or higher baseline anxiety.

- Inconsistent study plans in the past.

- Limited external support.

…you are statistically in the group that faces higher mental health risk with DIY self-study. In that situation, paying for structure is not indulgence. It is risk mitigation.

How to Protect Your Mental Health in Either Path

You can blow up your mental health in a course or preserve it in self-study. The modality is a risk factor, not destiny.

Some specific, evidence-aligned practices that matter more than people admit:

- Fixed daily cutoffs. Students who set a hard stop (for example, 10 hours maximum, or no work past 10 p.m.) consistently show better sleep and anxiety outcomes, regardless of prep style.

- Pre-defined “non-negotiables.” Exercise 3x/week, one social contact per week, therapy appointments—not things you “fit in if there is time.” Data from wellness programs show that students who keep even minimal physical and social activity have lower GAD-7 and PHQ-9 spikes.

- Scheduled adjustment points. Instead of panicking every time a score is off, you define specific days (e.g., at 6 weeks, 4 weeks, 2 weeks) when you are allowed to change the plan. That protects you from constant reactive changes, which correlate strongly with perceived loss of control and anxiety.

- Transparent metrics. Whether course or self-study, you use defined score ranges on practice NBMEs, not vibes, to decide if you are on track. Rumination thrives in ambiguity.

None of this is glamorous. But these are the behaviors that show up again and again in the lower-anxiety, higher-functioning subset of USMLE takers.

Where This Leaves You

You are not choosing between “smart” and “dumb” paths. You are choosing between different mental health risk curves, with different financial and time costs layered on top.

The data, imperfect but consistent, point here:

- Structured courses tend to lower average anxiety, burnout, and plan-related rumination, especially for the academic middle and for students with moderate baseline anxiety.

- Pure self-study can work exceptionally well for students with strong self-regulation, robust support, and low trait anxiety, but it carries higher risk of severe stress and schedule collapse for vulnerable students.

- Mental health outcomes during USMLE prep are not marginal. They affect not just your comfort but your capacity to learn, recall, and perform on exam day.

So you decide:

- What risk profile you are comfortable with.

- How much you value guardrails versus flexibility.

- How honest you are willing to be about your own psychological patterns.

With that clarity, you can pick a path without delusion. And then commit to protecting your mental health as fiercely as you protect your percentile rank.

The exam will pass. Your brain and your habits stay with you long after. Getting those right during USMLE prep sets you up for how you will handle boards, in-training exams, and certification tests for the rest of your career. The next big question is how you will manage that long game—but that is a conversation for another day.

FAQ

1. Are USMLE prep courses “worth it” purely from a mental health standpoint?

For many students, yes. Across multiple datasets, structured course users report roughly 10–15 percentage points lower rates of moderate–severe anxiety and burnout than self-study peers, particularly in the academic middle. That does not justify any price at any quality, but it does mean courses are not just “score boosters”; they often function as psychological scaffolding. The more you struggle with planning, doubt, and second-guessing, the higher the mental health return from structure.

2. Does self-study always mean higher stress?

Not always. Highly organized, low-anxiety students with a strong track record of independent studying can do very well with self-study and maintain good mental health. The problem is that many students overestimate their self-regulation capacity. When self-study goes wrong, it tends to go very wrong: unrealistic schedules, constant resource switching, severe sleep cuts, and last-minute panic. So the variance in outcomes is higher. You can be fine or completely overwhelmed.

3. How early should I decide between a course and self-study to minimize stress?

Decide at least 3–4 months before your dedicated study period. Data from wellness and academic support programs show that students who lock in a plan early and stick with it report lower chronic anxiety than those who keep “shopping” for strategies into the dedicated period. Late switches—especially adding a full course in the final 6–8 weeks—are associated with more stress and do not reliably improve scores. Early decision, then minor refinements, is a cleaner mental health trajectory.

4. If I cannot afford a full course, what is the next best option for my mental health?

You can approximate many mental health benefits of a course by constructing your own structure: a realistic day-by-day schedule, limited and pre-chosen resources, fixed weekly “review and adjust” times, and an accountability system (study buddy, small group, mentor, or advisor). Many schools provide free or low-cost coaching and sample schedules that you can adapt. The key is to reduce decision fatigue and ambiguity. The more you can externalize the plan—on paper, with a partner, or via school support—the less mental load you carry.

5. How do I know if my USMLE prep is harming my mental health enough that I should change course?

Look at specific indicators, not vague feelings. Red flags include: persistent sleep under 6 hours for more than a week, GAD-7 or PHQ-9 scores climbing into the moderate range, daily crying or panic episodes, complete loss of interest in non-study activities, or thoughts that the exam is “all that matters” or “not worth going on” if you fail. When those appear, students who seek help early—from counseling, academic support, or a trusted mentor—have much better outcomes. Sometimes that means switching from pure self-study to a structured plan, delaying the exam slightly, or scaling back unrealistic goals. The metrics give you permission to adjust before something truly breaks.