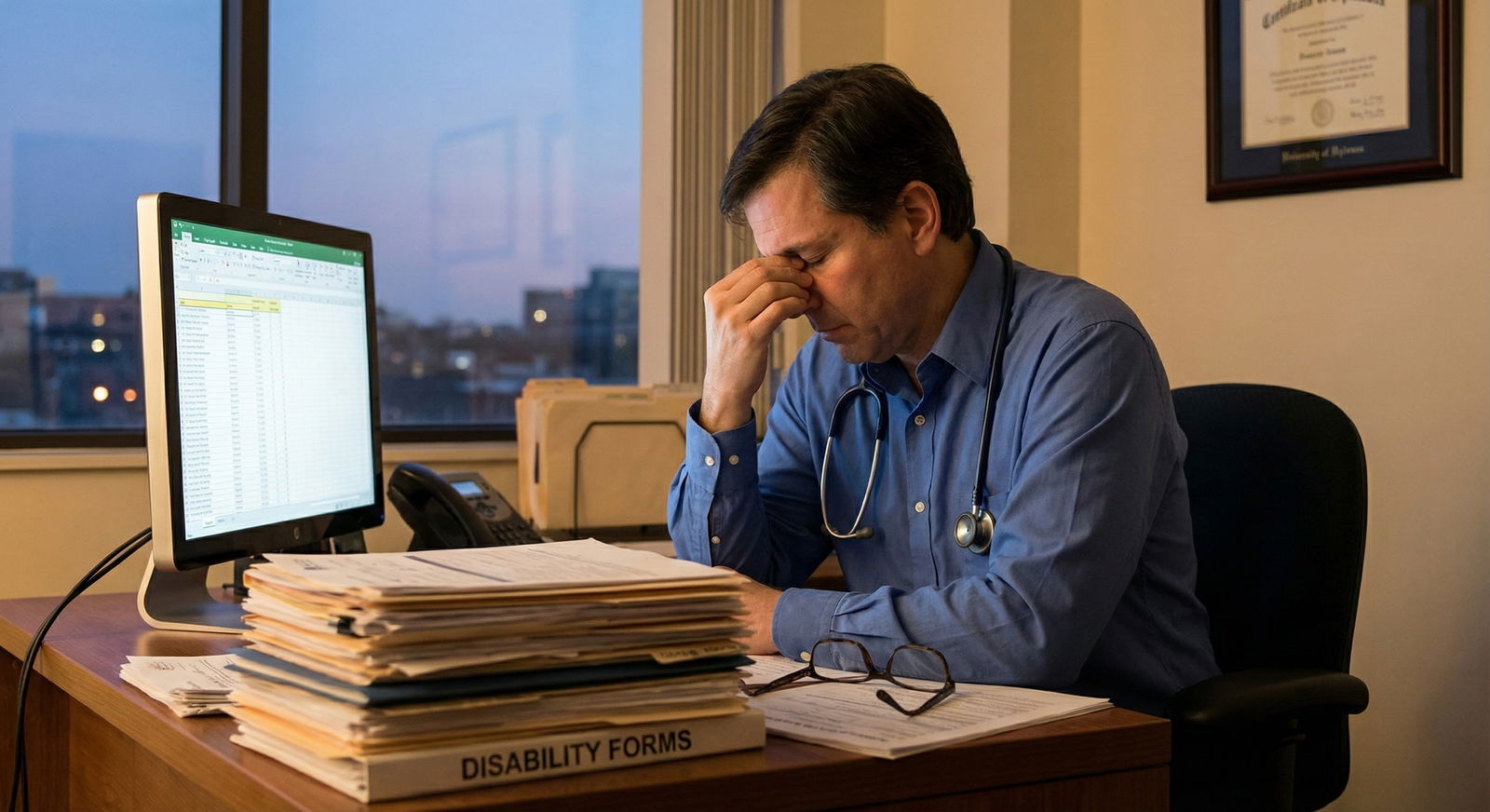

The fastest way to ruin your career is to treat disability paperwork as a “favor.”

If you take nothing else from this, take that. Disability forms are not kindness coupons. They are legal declarations, often under penalty of perjury, that tie together ethics, licensure risk, and patient trust. Treat them casually, and you are gambling with all three.

You are going to be asked to “help” with disability paperwork. By good people who are genuinely struggling. And by people who are not. Most physicians learn this the hard way—after they have already signed something they should not have.

Let me walk you through the mistakes that will cost you, and how to avoid stepping on landmines that look like innocent forms.

The core mistake: treating disability paperwork as customer service

The most common, most dangerous error is simple: thinking your job is to “get them what they need.”

No. Your job is to:

- Document what is medically true.

- Stay inside your scope and your actual knowledge.

- Communicate clearly when the medical facts do not support what is being requested.

When you forget that, you get sucked into “advocacy theater.” You are pushed—subtly or aggressively—into reshaping reality so the patient, friend, or colleague gets financial support, job protection, academic accommodations, or legal leverage.

Here is how that pressure usually sounds in real life:

- “Doc, can you just say I cannot work for a few months so I can keep my benefits?”

- “They said if my doctor writes that I am ‘totally disabled,’ they will approve it.”

- “Everyone else on my floor is getting this; I just need the paperwork to match.”

- “My lawyer said you just need to put the right wording.”

If you treat those as simple customer requests instead of ethical-legal dilemmas, you are already in trouble.

Red flag #1: Signing forms for people you barely know

This one is career suicide in slow motion: completing disability forms for someone you have seen once or twice. Or worse, not at all.

Common variants:

- A colleague asks you to “just sign” for their relative because “their old doctor retired.”

- A patient brings in years of outside records and wants you to fill out everything at the first visit.

- You inherit a chart where your predecessor had been generous with disability statements, and the patient expects you to simply continue.

Here is the rule you ignore at your peril: You should not certify functional impairment that you have not personally assessed over time, or that you do not understand well enough to defend under oath.

At a minimum, before you complete meaningful disability paperwork, you should have:

- A documented clinical relationship.

- Examination (physical or mental status) consistent with what the form asks you to attest to.

- Sufficient visits and history to understand the stability, chronicity, and impact of the condition.

- Relevant test results or specialist input when appropriate (e.g., neuropsych evaluation for learning disabilities, imaging or EMG for certain physical issues).

Red flag #2: Letting the patient (or lawyer, or HR) dictate the wording

You are not a scribe for someone else’s narrative.

The second major mistake: letting outside stakeholders tell you exactly what to say—sometimes even handing you pre-written phrases or draft letters to copy.

Real-world versions:

- “Here, my attorney printed the wording they need; can you just paste this into a letter?”

- “HR said they can only approve it if you write ‘no lifting over 10 pounds indefinitely.’ Can you put that?”

- “The school wants you to say I absolutely require solo testing, extended time, and no group work.”

If you use their script instead of your clinical judgment, you have flipped the roles. You are no longer an independent professional describing medical reality; you are part of someone’s strategy.

Correct approach:

- You read the requested wording.

- You decide what is medically accurate and supportable.

- You write your own statement, in your own words, aligned with your notes, exam, and data.

- You ignore or revise any requested phrases that overshoot the truth.

If a lawyer is involved, you document: “Attorney requested specific phrasing; my letter reflects my independent clinical judgment and record.” You are not on their team. You are on the side of the facts.

Red flag #3: Confusing sympathy with evidence

Feeling bad for someone is not evidence of disability.

I have seen residents fold because the story is heartbreaking: single parent, chronic pain, lost job, eviction looming. Yes, you are human. Yes, you should care. But your signature is not a social work tool.

You must separate:

- “This person is suffering”

from - “This person meets the formal criteria for disability / accommodations as defined by this agency.”

The mistake:

- Overstating functional limitations because you feel they “deserve a break.”

- Using phrases like “unable to work” for conditions where your own notes say “stable,” “improving,” “mild,” or “responding well to treatment.”

- Certifying permanence when the prognosis is uncertain.

Sympathy does not protect you when an insurer audits, a board investigates, or a judge reviews records that contradict your forms.

You are allowed to say “I believe you are struggling, but medically I cannot state what you are asking me to state.” That is actually what integrity looks like.

Red flag #4: Not understanding what you are actually certifying

Too many physicians sign forms without really reading the legal language.

Typical traps:

- Forms that say “I certify under penalty of perjury…” and you treat it like a school note.

- Questions asking whether the patient is “totally and permanently disabled from any gainful employment,” and you answer based on whether they can do their current job.

- Boxes asking if the condition “began” on a specific date, and you invent a date that sounds neat.

You must slow down and actually decode what is being asked:

- Are you certifying diagnosis only, or functional capacity, or prognosis?

- Are you certifying capacity for “any work” or “this specific job”?

- Are you being asked to estimate onset, or declare you “know” it started on X date?

- Does the form require you to certify “permanent” impairment? If so, are you qualified to say that now?

If you do not understand a question, you do not guess. You leave it blank, write “unknown,” or attach an explanatory note: “I can speak to current functional status but cannot reliably state onset date prior to my involvement.”

Guesswork is how honest doctors get accused of fraud.

Red flag #5: Overstepping your specialty and scope

Another frequent error: speaking authoritatively about disabilities outside your domain.

Examples:

- A primary care physician definitively certifying severe cognitive impairment without neuropsych testing.

- A psychiatrist certifying precise physical lifting restrictions they have never assessed.

- A surgeon declaring long-term vocational capacity for mental disorders they are not treating.

You are responsible for what you claim expertise in.

Safe practice:

- Limit your statements to what you directly evaluate and manage.

- When something is outside your scope, say so explicitly: “Assessment of detailed cognitive functioning and specific accommodations is best determined by a neuropsychologist; my role is treatment of major depressive disorder.”

- Ask for and incorporate specialist reports, but do not claim conclusions as if they are your own if you have not independently assessed them.

If a form pushes you to opine beyond your specialty, you can write: “Outside my scope to determine,” or “Refer to [specialty] for detailed functional assessment.”

Red flag #6: Sloppy documentation that does not match what you signed

This is where many well-meaning doctors are completely exposed.

You might genuinely believe the patient is disabled. You may be right. But if your chart does not match the severity, chronicity, or functional limitations you put on the form, you look dishonest—even if you are not.

Common mismatches:

- Disability form: “Severe back pain, unable to sit more than 10 minutes.”

Chart: “Back pain, mild to moderate, improved with PT, walks dog daily.” - Form: “Total occupational disability since 2021.”

Chart: “Patient working full time through mid-2023.” - Form: “Panic attacks daily, unable to leave house.”

Chart: “Panic attacks 1–2 / month, manages with coping skills, goes to gym 4x/week.”

If you are going to describe serious functional limits, your notes must include:

- Specifics: what the patient can and cannot do; for how long; with what symptoms.

- Longitudinal pattern: has it been consistent? Worsening? Fluctuating?

- Objective anchors: exam findings, testing, third-party reports when relevant.

If your documentation is thin and vague, you have no business certifying major disability. You are building a house with no foundation.

Red flag #7: Treating time-limited paperwork as permanent commitments

Another quiet trap: acting as if any disability certification is forever.

You see this when physicians:

- Refill the same “cannot work” statement for years without re-evaluation.

- Never specify time frames (“cannot work” vs “cannot work for the next 3 months pending reassessment”).

- Fail to document any plan for reassessment, rehab, or trial of return to work.

Result: you get locked into a narrative you once signed off on, long after the facts may have changed.

Better approach:

- Use time-limited language: “temporarily unable,” “anticipated duration X–Y months,” “will reassess at follow-up.”

- Document the plan in your note the same day: “Completed short-term disability paperwork for 8 weeks; goal to reevaluate at that time for potential graded return.”

- Be willing to say “no longer medically justified” when the condition improves.

You are not ethically obligated to perpetuate disability statements that no longer match reality. You are obligated to be honest about change.

Red flag #8: Letting personal fear or anger contaminate your judgment

Here is one people rarely admit out loud.

Your relationship with the patient colors how you handle their requests. You will be tempted to:

- Over-accommodate the patient who is charming, grateful, and “really likes you.”

- Stonewall the patient who is demanding, threatening, or has burned your staff.

Both are mistakes. Your obligation is to the truth, not to your feelings.

Watch for signs that emotion is steering you:

- You rush a form because you “do not want to deal with them again.”

- You say yes because you hate conflict and just want them out of your office.

- You say no reflexively without actually considering the clinical facts because you are annoyed.

If you feel yourself reacting emotionally, slow down. Stick to the record. Ask: “If this were a random patient I had never met, with this chart, what would I write?” Then do that.

How to handle requests the right way (without burning your career or your soul)

Now, the part that actually protects you.

You need a clear internal script and external process so you are not improvising every time someone slaps a form on your desk.

Step 1: Set expectations early

Do not wait until the first form appears.

From the first visits, especially with chronic conditions, say things like:

- “When it comes to disability or accommodation forms, I can only write what is medically accurate based on our records and my assessment. I cannot promise any particular outcome or wording.”

- “Sometimes what I observe clinically does not meet the criteria that agencies are looking for. In those cases, I will tell you clearly.”

This prevents the toxic assumption that your job is to “make it happen.”

Step 2: Slow down and actually review

When a form arrives:

- Read the whole thing, including the tiny legal print.

- Clarify who is asking: insurance, employer, school, government agency, attorney?

- Check what you are being asked to certify: diagnosis, function, prognosis, dates, or all of the above.

- Compare each major claim you are tempted to make with your chart.

If you find gaps—missing data, unclear timeline, no functional description—fix that first with a more thorough visit, exam, or additional testing.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Patient requests disability paperwork |

| Step 2 | Review request and form |

| Step 3 | Schedule focused assessment and gather data |

| Step 4 | Compare request with documented facts |

| Step 5 | Complete form using own wording |

| Step 6 | Explain limits and complete accurately or decline |

| Step 7 | Document rationale in chart |

| Step 8 | Adequate data and relationship? |

| Step 9 | Request matches clinical reality? |

Step 3: Use your own language, anchored to specific facts

On any narrative or free-text portion:

- Describe diagnoses plainly.

- Describe function concretely (“can stand for 5–10 minutes before needing to sit,” “misses 3–4 days of work per month due to flares”).

- Avoid legal-sounding absolutes unless you really mean them and can back them up (“permanent,” “total,” “unable to perform any work”).

When in doubt, you can say: “Based on my current evaluation, the patient is limited in X ways. I cannot comment on other types of work or long-term prognosis beyond [time frame].”

Step 4: Be honest when you cannot support the request

You will have to say no sometimes. Or at least say, “not in the way you are asking.”

Examples of ethical responses:

- “I agree you have significant symptoms, but based on your function and work duties, I cannot say you are completely unable to work. We can explore accommodations instead.”

- “What you are asking me to certify does not match what I have documented over the years. I cannot change your medical record to fit this form.”

- “I can complete the medical sections honestly, but I cannot state that you meet the legal definition of disability; that determination is made by the agency.”

You are allowed to be the one who does not play along. In fact, you are supposed to be.

Comparison: risky vs protective approaches

| Situation | Risky Response | Protective Response |

|---|---|---|

| New patient asks for long-term disability at first visit | Complete form based on patient report alone | Explain need for longitudinal assessment and limited initial statement |

| Lawyer sends preferred wording | Copy/paste phrasing into your letter | Use your own wording based on chart; note independence of judgment |

| Chronic stable condition with request for “total disability” | Sign off to “help them out” | Document function, offer accommodations, decline to certify total disability if unsupported |

| Vague documentation but severe claims on form | Sign anyway to avoid conflict | Update records with detailed assessment or decline until data supports claims |

| Out-of-scope issue (e.g., cognitive capacity) | Guess or adopt another clinician’s opinion as your own | Limit comments to your domain; refer to appropriate specialist |

The legal and professional consequences people pretend do not exist

You will hear colleagues say, “Everyone does it,” or “These companies are awful; I do not mind gaming the system a bit.”

Those colleagues are not going to show up at your board hearing.

Potential fallout if you repeatedly treat disability paperwork as favors:

- Board complaints alleging fraud or unprofessional conduct.

- Insurer audits, recoupment demands, or designation as a “high-risk” provider.

- Being subpoenaed and cross-examined in court, with your own contradictions used against you.

- Loss of institutional trust; HR or risk management quietly flagging you as a liability.

- In extreme, repeated cases: criminal exposure if clear falsehoods were certified under penalty of perjury.

You are not paranoid if you treat these forms seriously. You are simply awake.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What should I do if a patient threatens to file a complaint if I do not sign the way they want?

Stay calm, and do not negotiate under threat. Document the interaction carefully: what was requested, what you explained, and any threatening language. Then complete only what is medically accurate, or decline if you truly cannot complete the form ethically. If you are in an institution, loop in risk management or your supervisor early. Boards and administrators take a lot more seriously “I refused to falsify a document and the patient got angry” than “I signed something I knew was wrong because I was scared.”

2. Can I charge for the time it takes to complete disability paperwork?

Usually yes, if your local laws, payer contracts, and institutional policies permit. Document the time and treat it as non-covered administrative work, not bundled into a brief visit. The key is transparency: patients should know ahead of time that complex forms may incur a fee and require scheduled time. Charging reasonably for your time can actually reduce pressure to rush and check boxes blindly.

3. What if I inherit a patient who has been on disability for years based on another doctor’s generous forms?

You are not obligated to perpetuate someone else’s judgment. Start with a fresh, honest assessment. Review prior records, but base your current forms on your own evaluation and what you can support now. If your conclusions differ—especially if you think the prior disability status is no longer medically justified—communicate that clearly and respectfully to the patient, and document it. “Another doctor did it” is not a defense if you continue a pattern you believe is inaccurate.

Two things to remember.

First, disability forms are not favors; they are sworn statements of medical fact. Treat them that way every single time.

Second, your job is not to guarantee an outcome. Your job is to describe reality honestly, within your expertise and your records. Anyone who pushes you beyond that—patient, lawyer, employer, or agency—is asking you to trade your integrity for their convenience. Do not make that trade.