Already a Partner or Executive? How to Step Back to Become a Premed

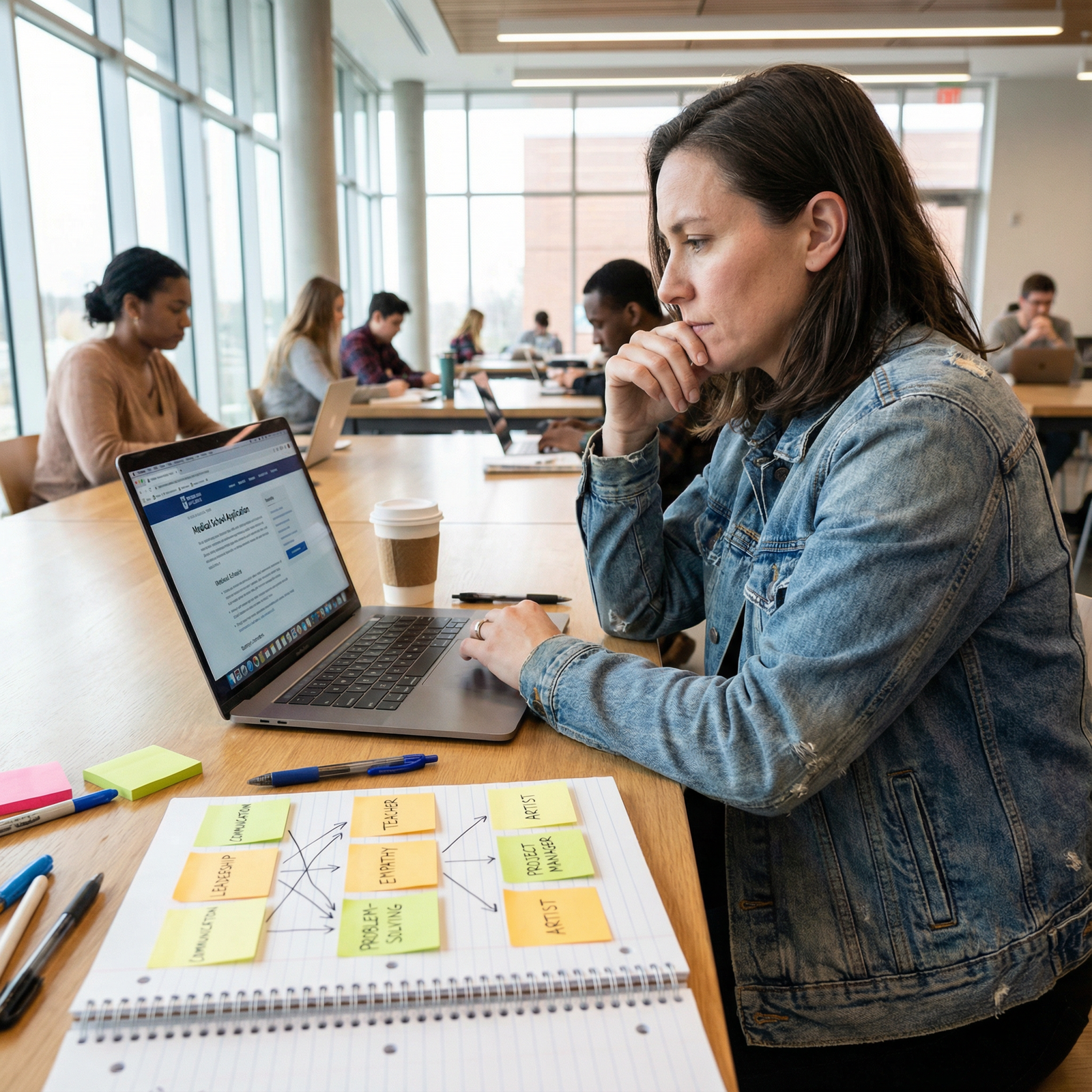

What do you actually do when you’re a partner or senior exec with a mortgage, kids, and prestige—and you realize you want to start over as a premed?

Not theoretically. Logistically. This year. With your current title on LinkedIn and everyone expecting you at Q4 strategy meetings.

I’m going to walk you through this like we’re in your office with the door closed and you just said: “I think I need to quit and go back to school. Am I insane?”

You’re not insane. But you are in for a serious multi-year project that will blow up your current identity if you do it wrong.

Let’s do it right.

Step 1: Reality Check — Can You Actually Do This?

Before you look up a single prereq or MCAT course, you need brutal clarity on three things: time, money, and support.

1. Time: How Many Years Are We Talking?

From today to fully trained attending:

- 1–2 years: Premed coursework (if you need a full slate of prerequisites)

- 1 year: MCAT + application cycle

- 4 years: Medical school

- 3–7 years: Residency (plus fellowship if you go that route)

You’re looking at:

- Early 30s? Very realistic. You’ll still finish training in your 40s.

- Late 30s? Still doable, especially for primary care, psych, FM, IM, even EM.

- 40s? Possible, but don’t sugarcoat the grind. You’ll be training with people a decade+ younger, possibly while paying for college for your own kids.

This isn’t to scare you. It’s to stop the “I’ll just see how it goes” fantasy. You either commit to the timeline or you do not.

2. Money: Stop Hand-Waving This

You are not a 22‑year‑old who can live on ramen. You have responsibilities.

- Lost income (your current comp vs likely income during school/residency)

- Tuition for:

- Post-bacc or DIY premed classes

- Medical school (public vs private is a big swing)

- Living expenses for:

- You

- Family (if applicable)

- Childcare

Do a rough comparison.

| Item | Current State | Premed/Med School State |

|---|---|---|

| Annual gross income | $250,000 | $0–$40,000 (side work) |

| Annual tuition/fees (post-bacc/MS) | $0 | $20,000–$60,000 |

| Med school tuition (annual) | $0 | $40,000–$70,000 |

| Years without full income | 0 | 7–10 |

| [Loan debt at graduation](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/nontraditional-path-medicine/loan-repayment-scenarios-for-latecareer-switchers-entering-medicine) | $0–$50,000 | $200,000–$400,000 |

This table isn’t meant to be exact. It’s meant to scare you enough to take this part seriously. Talk to a financial planner who has seen physicians’ finances. Many high earners going into medicine underestimate the long tail of lost opportunity cost.

3. Support: Who Has to Be On Board?

If you’re married, have a partner, kids, or dependents, this isn’t your decision. It’s a team decision.

You need one long, uncomfortable conversation that covers:

- “Here is how many years of training we’re talking about.”

- “Here is what our life will look like when I’m a resident working nights/weekends.”

- “Here is the income drop we’re facing. Here’s how we’d cover it.”

- “Here’s the upside—and here’s what might never pay back financially.”

If your partner’s response is something like, “We’ll figure it out later,” you have a red flag. They need to understand the scale before you blow up your career.

Step 2: Decide Your Exit Strategy From Your Current Role

You’re not just “leaving a job.” You’re stepping down from an identity: partner, VP, C‑suite. If you handle this badly, you torch bridges you might desperately want later (for consulting income, letters, or just sanity).

Option A: Gradual Step-Back While You Start Classes

If your current role has any flexibility, this is usually the smartest path.

Aim for:

- 0–6 months: Stay full-time; start with 1 evening/weekend class

- 6–18 months: Shift to reduced hours or advisory role while ramping up coursework

- Post-classes: Step away more completely for MCAT/application sprint

You might:

- Move from partner to “of counsel” or “senior advisor”

- Convert from C‑suite to paid board member or consultant

- Negotiate remote/part-time project-based work

You present it as: “I’m pivoting into a different domain and need more flexibility. I’d like to transition into an advisory capacity over 12 months.” You do not need to announce “I’m becoming a premed” to everyone on day one. Medicine is a black box to many execs; you’ll get noise, doubt, and sometimes active sabotage.

Option B: Hard Exit, Then Full-Time Premed

This works when:

- Your job is all-or-nothing

- You have 12–24 months of expenses saved

- You can’t realistically juggle exec hours and real science coursework

If you go this route, set a clean date:

- “I will resign effective August 31.”

- Backward plan your final major projects and transitions.

- Cement relationships for future recommendation letters before you announce.

Then for the love of your future self, don’t quit and then “figure out” your premed plan. Have your first semester enrolled before you walk out.

Step 3: Build a Premed Plan That Respects Your Age and Experience

You’ve been working at a high level. You’re not going back to “just take some classes.” You’re engineering a career pivot.

1. Map Your Academic Gaps

You need answers to:

- Do you already have a bachelor’s? (I’m assuming yes.)

- When did you graduate?

- What science did you take, and how old are those credits?

Med schools generally expect:

- 1 year gen chem + lab

- 1 year orgo + lab

- 1 year biology + lab

- 1 year physics + lab

- 1 semester biochem

- 1 semester stats

- English / writing

Some are flexible, but you can’t guess. Create a basic grid.

| Course | Already Have? | Grade | Year Taken | Need to Retake? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen Chem I/II | No | — | — | Yes |

| Organic I/II | Yes | B+/A- | 2005 | Probably |

| Biology I/II | No | — | — | Yes |

| Physics I/II | Yes | B/B- | 2004 | Yes (old/weak) |

| Biochemistry | No | — | — | Yes |

| Statistics | Yes | A | 2018 | No |

Anything older than ~7–10 years is suspect, especially if your MCAT will be heavy in that content. And if your GPA was mediocre, you need fresh As to prove academic readiness.

2. Choose Your Structure: Formal Post‑Bacc vs DIY

You’re not just “taking classes.” You’re managing risk and optics.

Formal post-bacc (e.g., Goucher, Scripps, Bryn Mawr, Columbia):

- Cohort of career changers

- Strong advising and linkage options

- Expensive, often full-time, often inflexible with work

- Very attractive to admissions if you crush it

DIY at local university or state school:

- Cheaper

- More flexible with part-time work

- You handle your own advising, letters, and sequencing

- Works perfectly fine if you get As and a strong MCAT

You, as a partner/executive, may be tempted by big-name post‑baccs. They’re great, but not magic. If you’ve got a family and mortgage, a solid state post‑bacc taken seriously can be the smarter play.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Day job/consulting | 35 |

| Classes/labs | 8 |

| Study/homework | 15 |

| Family/personal | 20 |

| Admin/logistics | 5 |

Step 4: Manage Identity Whiplash (This Will Mess With Your Head)

You’re used to being the person everyone defers to. Now you’re asking a 26‑year‑old lab TA how to use the pipette correctly.

I’ve watched this crush people more than the content.

Here’s the mental reset you need:

You’re not “starting over from zero.”

Your leadership, communication, and problem-solving skills will be huge assets later. But in orgo lab, you are a beginner. Act like one.Drop the status armor.

Nobody in your physics class cares that you used to manage $200M budgets. They care that you pull your weight in group work and don’t talk over people.Accept looking stupid. A lot.

The person who can’t tolerate confusion doesn’t last long in medicine. If you can sit in discomfort—of not knowing, of not being the best—you’ll do fine.

On paper, you’re “older, accomplished, impressive.” In the actual premed grind, you’re just another student who has to learn Hess’s law and renal physiology. That’s healthy. That’s good.

Step 5: Build Clinical and Volunteer Experience That Matches Your Background

You’ll be tempted to lean on your title and assume that makes you special. Admissions will be mildly interested in your partner/exec status for about 3 minutes. Then they’ll ask: “Have you worked with patients?”

You need direct exposure.

Clinical Exposure: What You Actually Need

You want:

- Shadowing physicians (primary care + your intended specialty interests)

- Clinical volunteering or paid work with patient contact (if possible)

Real options that work for busy professionals:

- One half-day per week in a free clinic or FQHC

- Scribing (if you’re willing to work evenings/weekends)

- Hospital volunteer roles with some patient interaction

- Hospice volunteering (high impact, big emotional exposure)

You don’t need 2,000 hours. But you do need enough to convince yourself and adcoms you’re not romanticizing medicine. 100–200 hours of meaningful clinical exposure is a good target.

Nonclinical Service: You Can’t Just Be Corporate

Medical schools care deeply about service, especially to underserved communities. You likely have leadership and mentorship baked into your career, but you should add some visible, consistent service:

- Tutoring disadvantaged students

- Food bank or shelter volunteering

- Board work is fine, but don’t hide behind boards only—have some hands-on activity too

Your story can’t read as “I’m used to being highly compensated and respected, now I want to be highly compensated and respected in a different field.” That’s death. They need to see service, humility, and actual sweat.

Step 6: Craft the Narrative: From Executive to Future Physician

Eventually, this all has to make sense in an AMCAS personal statement and in interviews.

You need a story that:

- Explains why you’re leaving a successful, stable, respected position

- Shows you’re not running away from burnout, but running toward something

- Demonstrates sustained commitment, not a midlife crisis hobby

The rough arc usually looks like:

- Inciting reality: Something that made medicine real and urgent—a family illness, an experience leading a healthcare project, time spent embedded in a clinical team.

- Investigation phase: You didn’t just immediately tank your career. You shadowed, volunteered, took a class, talked to physicians, tested the idea.

- Deliberate choice: Here’s the moment you decided, fully informed, to commit. This is where your partner/executive brain kicked in: spreadsheet, timeline, financial modeling.

- Evidence of follow-through: A‑level science work, MCAT score, clinical hours, letters that say “this person executes.”

Avoid two traps:

“I’ve always wanted to be a doctor but did business instead.”

They’ll ask: so why now, and what changed?“I was burned out by corporate greed and want meaning.”

Every med student and resident also burns out. Medicine is not a serene monastery of purpose. Say you want meaningful, patient-facing work, but don’t romanticize.

Step 7: Protect Your Future Self During This Transition

This is a long game. And long games require guardrails.

1. Maintain Optionality

If possible, keep at least one of these alive:

- A low-maintenance consulting lane in your current field

- A maintained license or credential you can fall back on

- Strong relationships with 2–3 senior people who’d rehire you if this path derails

You’re making a big bet. Don’t make it binary if you don’t have to.

2. Physical Health

You’re going to be older than your classmates. Fine. Then you need to outperform them in stamina.

Baseline goals before med school:

- Decent cardiovascular fitness (you can handle long clinic/hospital days)

- Manage existing health conditions now (BP, weight, sleep apnea, etc.)

- Stable sleep routine that doesn’t destroy you

The med school grind doesn’t care that you’re 43 with a bad back. You have to care now.

3. Emotional Boundaries

Expect:

- Old colleagues gossiping: “Midlife crisis?”

- Family asking: “Why would you give all this up?”

- Classmates who see you as The Old Person

You can’t spend energy defending your decision 24/7. Have a short, calm script and reuse it:

“I had a great run in [field]. But I realized I wanted to work directly with patients and stay closer to the human side of healthcare. I did my homework for a couple of years and decided to commit.”

And then you move on. You don’t owe anyone a TED Talk.

Step 8: Concrete 12-Month Action Plan

Let me strip the theory away. Here’s what your first year could actually look like if you’re serious.

Months 1–3

- Talk to spouse/partner/family. Make or break conversation.

- Meet with:

- A premed advisor (can be at a local college or private)

- A financial planner

- At least 2 physicians (ideally in different specialties)

- Start one small clinical exposure: 4 hours/month shadowing or volunteering

Months 3–6

- Enroll in 1–2 foundational science courses (likely at night or part-time)

- Start serious self-study in basic chem/biology if you’ve been away a long time

- Explore whether your firm/company will support a gradual step-back

- Create a written 5–10 year timeline including:

- Coursework

- MCAT window

- Application cycle

- Expected start of med school

Months 6–12

- Increase course load if feasible (2–3 classes)

- Lock in regular clinical volunteering (2–4 hours/week)

- Start light MCAT prep—familiarization, not full commitment yet

- Decide: formal post‑bacc vs continuing DIY

- Make a final call on job transition timeline

At 12 months, you should no longer be in “thinking about medicine” land. You should be tangibly on the path: transcript building, clinical experiences, and a visible shift from executive-only identity to “professional turning physician.”

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. Am I “too old” to start this if I’m in my late 30s or early 40s?

No, not automatically. I’ve seen 40‑something BigLaw partners and senior tech VPs get into med school. But age does change the risk–reward ratio. You’ll likely graduate med school in your mid‑40s and finish residency in your late 40s or early 50s. If you’re aiming for long, surgically intense or ultra‑competitive specialties, the math is harsher. If you’re drawn to internal medicine, family med, psych, peds, or similar, your age is less of a practical problem. The non-negotiable part is that you must be brutally honest about health, stamina, finances, and family dynamics.

2. Should I tell my firm/company early that I’m planning to go into medicine?

Usually, no. Not at first. Early on, you’re still validating whether this path is actually right for you. Telling partners or board members you’re “thinking about quitting to go to med school” can tank your leverage, assignments, and political capital long before you’re certain. Start by exploring quietly: classes at night, shadowing, speaking with advisors. Once your plan is concrete and you’ve got dates in mind, then you can craft a professional, respectful exit or transition conversation that focuses on your next chapter—without inviting everyone to weigh in on your life choices.

3. Will admissions committees take me seriously coming from a high-status non-medical career?

Yes—if you do the work like everyone else. Exec/partner status might get their attention for 30 seconds, but then they go straight to the same questions they ask any applicant: Can you handle the science? Do you understand medicine beyond TV shows and LinkedIn posts? Are you service‑oriented or just chasing prestige? If your app shows A‑level recent coursework, a solid MCAT, substantive clinical exposure, and a coherent story of why you’re changing lanes, they’ll treat you as a serious candidate. If your app reads like “I’m important and therefore should be admitted,” you’ll get quietly filtered out.

4. What if I start this process and realize I don’t actually want to be a doctor?

That’s a win, not a failure. The whole point of the early phase—classes, shadowing, volunteering—is to test the hypothesis that medicine is worth the sacrifice for you. If a year in you feel a deep “nope,” you’ve just saved yourself 7–12 years of misalignment. You can step back, keep your professional relationships, and perhaps pivot toward something healthcare-adjacent: hospital administration, digital health, policy, biotech. That’s why I push you to keep optionality in your old field and avoid torching bridges. You’re allowed to explore and then decide no, this isn’t it.

With the decision, the planning, and the first steps laid out, your job now is simple—start. First class, first shadowing shift, first awkward “I’m going back to school” conversation. Once those are in motion, we can talk about the next battlefield: the MCAT and the application year. But that’s a story for another day.