The idea that late‑career doctors are automatically less competitive for fellowships is lazy thinking dressed up as wisdom. Age is a variable; it is not a verdict.

If you are a non‑traditional or late‑career future physician worrying about fellowship options before you have even started medical school, you are asking the right question—but most people are giving you the wrong answers.

Let me be blunt: programs are not sitting around saying “we hate older applicants.” They are asking, “Will this person succeed here, finish on time, and represent our program well?” Age only matters when it interacts with those questions: training length, visa status, financial risk, health, prior performance, and sometimes culture fit.

That means older applicants can be both more competitive and less competitive depending on how they play their cards. The difference is usually not their birth year. It is their record.

Let’s pull this apart properly.

What the data actually shows (and what it does not)

There is no large, clean, multi‑specialty dataset where you can look up “match rate for 28‑year‑old vs 42‑year‑old cardiology applicants.” Anybody claiming exact percentages is guessing.

But we do have several facts that matter:

ACGME and NRMP do not have upper age limits.

No official age cap for residency or fellowship in the US. Some countries have formal age cutoffs; the US does not.Programs care about board scores and performance far more than age.

NRMP Program Director Surveys (for fellowship‑level and residency‑level) are boringly consistent: the top factors are things like:- USMLE/COMLEX scores and pass history

- Residency program reputation and letters

- Prior academic productivity (for competitive subspecialties)

- Professionalism and interview performance

Age is nowhere on the “ranked factor” charts. It only sneaks in behind the scenes when PDs talk about “career trajectory” or “future potential.”

Older applicants are over‑represented in some fellowships, under‑represented in others.

Look around any geriatrics or palliative care fellowship. Many fellows are 30s–40s, sometimes older. Hospitalist‑to‑fellow transitions are common there.

Now look at something like pediatric surgery fellowship—hyper‑competitive, long training pipeline, heavy operative volume. You will see fewer late‑career pivots.Surveys and anecdotes from PDs show hesitation with very long‑training pathways for older applicants.

I have heard a PD say, word for word:

“If someone is going to finish training at 48 and then do another two‑year fellowship to work clinically for six years before retiring, I start to wonder how long the ROI is—for them and for us.”

That is not age discrimination in the legal sense. It’s financial and strategic thinking. Right or wrong, this is how many of them think.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Board Exams | 95 |

| Letters/Residency Reputation | 90 |

| Research | 75 |

| Interview | 80 |

| Age | 10 |

Do not misread that chart. Age is not “0.” It just rarely shows up as a primary factor. It mainly acts as a tiebreaker or a lens: “Does this person’s story make sense?”

The myths that hurt late‑career applicants

The danger is not that programs will secretly blacklist you for being 35 or 45. The danger is that you will internalize bad myths and sabotage yourself way earlier—in premed and medical school—because you assume things are impossible.

Let’s kill the big ones.

Myth 1: “If you start medicine after 30, fellowship is basically off the table.”

Wrong. Completely.

Do the math for a US path starting med school at 32:

- Med school: 4 years → 36

- IM residency: 3 years → 39

- Cardiology fellowship: 3 years → 42

You finish cardiology fellowship at 42. That leaves 20+ years of full practice for most people. Programs know this. Many cardiology, GI, heme/onc fellows are in their late 30s and early 40s—especially those who took time for PhDs, research, prior careers, or military service.

Where this myth has some traction is when:

- You’re starting residency in your mid‑40s and aiming for a 3‑year fellowship after a 5–7 year core residency (like neurosurgery → spine, plastics → microsurgery, etc.), or

- You’ve already worked 10–15 years as an attending in something unrelated and now want to re‑enter a long training pipeline.

Those scenarios aren’t impossible, just much harder to sell.

The takeaway: starting med school or residency in your early to mid‑30s does not close the door to most fellowships. It just means you cannot afford to be mediocre and then hope “potential” will carry you.

Myth 2: “Programs think older applicants can’t handle the hours.”

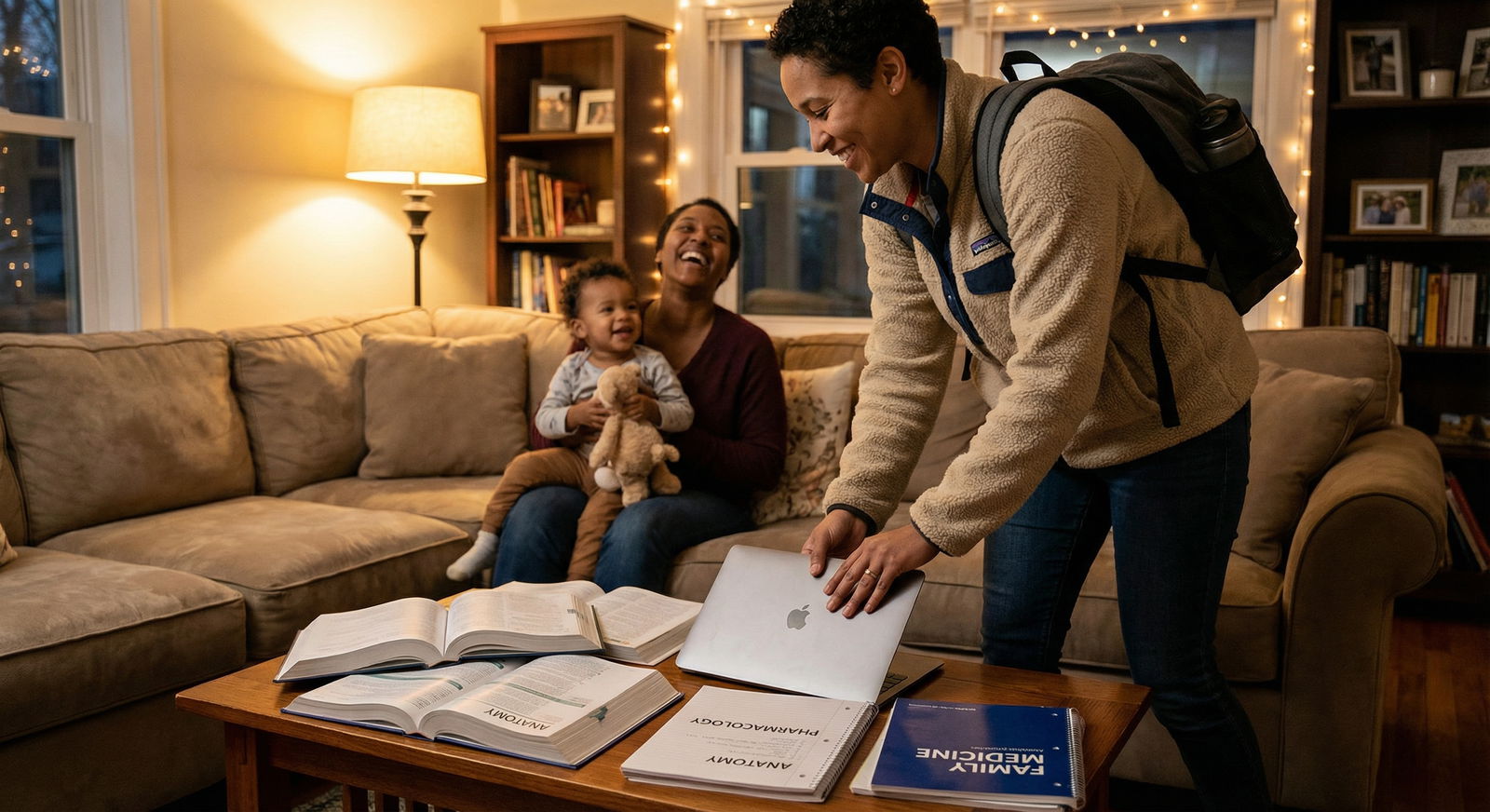

I have watched 28‑year‑olds crumble on night float and 42‑year‑olds with kids and mortgages calmly outwork everyone. Age isn’t the real variable. Capacity and habits are.

What PDs actually worry about:

- Health issues that might limit call or procedures

- Burnout risk in people who already sound exhausted before they even start

- “Set in their ways” behavior that clashes with learning culture

Older trainees can raise red flags if they present as inflexible or perpetually tired. That is a presentation issue, not an automatic conclusion from your birthdate.

If your story is: “I left a 60‑hour‑a‑week engineering career to do medicine; I know exactly what I’m signing up for,” you have defused half the concern.

Where age really does change the game

You cannot wish reality away. Age does alter the playing field in some concrete ways. You just need to see it clearly instead of swallowing vague “you’re too old” warnings.

| Factor | Younger Applicant Impact | Late‑Career Applicant Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Training length | Minor concern | Can be a major concern for very long paths |

| Research runway | Long timeline to build niche | Must be more targeted and efficient |

| Program risk tolerance | Assumed long future career | They question long‑term ROI more |

| Life obligations | Often fewer | Family/financial constraints seen as risk or as maturity, depending on framing |

| Flexibility to relocate | High | Often lower, which shrinks options |

Training length and “ROI thinking”

Fellowship is an investment—for you and for the program. Programs get:

- Clinical labor at fellow salary

- Academic output

- Reputation when fellows succeed as attendings

If you’re 29 and finishing a 7‑year neurosurgery + 2‑year fellowship track at 38, that’s decades of impact. If you’re 49 and finishing at 58, some places will quietly balk.

This shapes which fellowships are realistic late‑career:

- One‑year or two‑year fellowships after core training (e.g., geriatrics, palliative, sleep medicine, some non‑ACGME fellowships) are much easier to justify at older ages.

- Super‑long, hyper‑competitive pipelines that already hesitate with any non‑linear path (like peds surgery, some advanced IR/IN, super‑subspecialized procedural fellowships) will be tougher.

Notice I said “tougher,” not “impossible.” There are 40‑something matched fellows in brutally competitive specialties. They just come in with near‑perfect records and crystal‑clear narratives.

Geography and family constraints

You know the script at fellowship interviews:

“So, are you geographically flexible?”

If you are 26, single, and say, “I’ll go anywhere,” you just increased your odds. When you are 41 with kids in school and a partner with a career, “anywhere” may be a lie.

Reality: older applicants often have tighter geographic constraints. That shrinks the denominator of programs you can apply to. Fewer programs = fewer shots.

That is not age discrimination. That’s math.

If you are premed or early in medical school and you already know you will be geographically constrained later—because of family, caregiving, or a spouse’s job—then you cannot coast. You will be competing in one region instead of five. You will need a stronger application per slot.

How late‑career doctors actually win fellowships

Here is where contrarian reality kicks back in your favor: the traits non‑traditional students often bring—discipline, focus, clear “why”—are exactly what make fellowship programs drool.

I’ve watched late‑career residents outmatch their younger peers because they stopped believing the fantasy that “there’s always time to figure it out.”

They commit to a path earlier—paradoxically

The 28‑year‑old med student who thinks, “Maybe I’ll do derm or maybe neurosurg or maybe EM, I’ll just see what happens,” usually ends up in the middle of the pack at everything.

The 37‑year‑old former nurse who says, “I’m going into pulmonary/critical care, full stop,” starts building that application from M2:

- Chooses research with a pulmonary attending

- Takes electives in MICU, consults, advanced ventilator management

- Shows up to conferences and journal clubs long before residency

- Aligns their Step 2 CK performance and clinical grade hustle with that single target

By the time fellowship applications hit, their file screams “obvious fit.” Age works for them by making their story coherent.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Premed Late-Career |

| Step 2 | Focused Med School Plan |

| Step 3 | Targeted Residency Choice |

| Step 4 | Early Fellowship Mentorship |

| Step 5 | Research & Electives Aligned |

| Step 6 | Competitive Fellowship Application |

They leverage prior career capital instead of hiding it

The worst move older applicants make is pretending their prior life doesn’t exist. “I was in business but now I just want to be a regular doctor.” That wastes your advantage.

Example: you spent a decade in data science or engineering and now you want cardiology or critical care. Programs are drowning in big‑data projects:

- Outcomes research

- Machine learning risk models

- EHR optimization projects

You show up saying, “Before medicine, I built predictive models in industry; here’s how I’ve already applied that in residency QI on sepsis,” and suddenly your age is not a weakness. It is a feature.

Same with teaching, leadership, military service, nursing, PA experience—translate it. Older applicants who do this well often become more attractive to academic fellowships than cookie‑cutter younger peers.

They run a disciplined numbers game

Older residents who successfully match into competitive fellowships generally:

- Apply more broadly, not less, within their geographic and specialty constraints.

- Network intentionally: meeting PDs at national meetings, asking to present work, emailing with purpose.

- Avoid “wasted” research—projects that have no path to a poster, talk, or paper. They don’t have 5–7 extra years to dabble.

You cannot fix age. You can fix all of that.

What this means for you as a premed or med student

You’re in the “Premed and Medical School Preparation” phase. Fellowship feels like a lifetime away. But this is exactly when non‑traditional and late‑career students either quietly set themselves up for success—or box themselves in.

Step 1: Be brutally honest about timeline and goals

Run actual numbers, not vibes.

If you’re:

- 29, applying to med school

- Planning IM → cardiology or heme/onc

- Healthy, willing to move, and ready for 60–70 hour weeks through your 30s and early 40s

Then yes, fellowship is absolutely realistic if you perform.

If you’re:

- 42, with major family obligations, limited ability to relocate

- Aiming for neurosurgery → complex spine fellowship while insisting on one metro area

Then you’re trying to win a statistical lottery. That does not mean don’t do medicine. It means pick a path whose training length and competitiveness match your constraints.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| FM no fellowship | 32 |

| IM + Cards | 42 |

| GS + Surg Onc | 43 |

| Neurosurg + Spine | 45 |

These are approximate ages assuming med school start in late 20s and typical training durations. The message: some paths are simply longer games.

Step 2: Front‑load excellence, not indecision

Because you have less “career runway,” you cannot spend five years being average and then expect to switch on excellence magically for fellowship. Late‑career physicians who match fellowships almost always:

- Crush Step 2 CK / Level 2 and core clinical rotations

- Build relationships with at least two potential letter writers in their target field early

- Say yes to projects that move the needle and no to fluff

You don’t need perfection. You do need density—of performance, of alignment, of signal.

Step 3: Control the story—or someone else will

At some point in an interview, someone will look at your CV, look at your age, and ask some version of:

“So walk me through your path and why now.”

This is your exam. Not a trap.

If your answer is apologetic, defensive, or fuzzy (“I was lost for a while”), they mentally dock you. If your answer is coherent and forward‑facing (“I spent 10 years in X, realized I wanted Y, here’s what I’ve already done to prove this isn’t a phase”), then age becomes context, not liability.

Late‑career doctors who do well in fellowships almost always project three things:

- Agency: you chose this deliberately, not by default.

- Stamina: you know what long, hard work feels like and still signed up.

- Direction: you have a clear sense of what you’ll do after fellowship.

Programs bet on that.

The uncomfortable truth about “age discrimination”

Let’s separate two realities that people like to conflate.

Legal / ethical age discrimination – “We don’t take people over 40.” This is not allowed, and programs will never say it out loud even if they privately feel uneasy about older applicants.

Rational assessment of training economics and trajectory – “This applicant will be 52 when they finish; they say they want academic research but have zero portfolio; we’ll get five clinical years out of them; are we the right fit?”

That second one is not going away. You might not like it, but you need to understand it.

So are late‑career doctors “less competitive” for fellowships? On average, in long, elite, research‑heavy fellowships with deep applicant pools, yes, the bar is higher for them. Because the bar is higher for any applicant whose story creates more questions.

But “less competitive” does not mean “not viable.” It means you don’t get the luxury of drift.

The bottom line for you

If you’re a non‑traditional or late‑career person still at the premed or med school prep stage, the fellowship question is not a reason to quit. It is a reason to be sharper.

Your real constraints are:

- Training length relative to your age and health

- Geographic and family flexibility

- Willingness to sustain intense effort in your 30s, 40s, or beyond

- Ability to produce a tight, credible narrative backed by performance

Everything else—the vague fear that “programs don’t want older people”—is mostly noise.

Years from now, you won’t be replaying anonymous forum posts about how you were “too old” for GI. You’ll be living one of two lives: the one you built deliberately despite the odds, or the one you backed away from because of other people’s anxiety.