It’s 4:30 p.m. You’re on your third week of an internal medicine rotation. You have 12 notes still unfinished, your intern just asked you to “go re-examine that patient one more time,” and you can feel your soul leaving your body as you open yet another progress note template.

But last night? You stayed up an extra hour happily debugging some R code for a project. You got a little dopamine hit when your regression finally ran. You actually enjoyed reading a dense JAMA paper that your PI sent you.

So now you’re asking yourself:

“I’m burned out on clinics, but I actually enjoy research. Did I pick the wrong path? Should I quit MD and do a PhD? Should I add a PhD? Or am I just fried and overthinking it?”

Good. That’s the right set of questions. Now let’s sort out what to do next.

Step 1: Separate Three Different Questions

Before you make any drastic move, you need to separate three questions you’re unconsciously mixing:

- Am I burned out from this current clinical environment or from clinical medicine as a whole?

- Do I want to leave clinical medicine, or do I want to add research to it?

- Are my feelings about research based on real sustained interest, or is research just the only part of my life that currently feels in my control?

You cannot answer these in your head while exhausted on call. You need data from your own life.

So we’re going to run a structured, real-world experiment on you.

Step 2: Diagnose the Burnout (Before You Torch Everything)

First: you feeling burned out doesn’t automatically mean you hate medicine. It might just mean your current rotation sucks. Or your team sucks. Or your sleep sucks.

You need to figure out which.

Ask yourself, very concretely:

- Does any part of patient contact feel meaningful, even once a week?

- Do you dread all patient-related tasks, or mainly:

- Documentation?

- “Scut”?

- Rude staff / toxic team dynamics?

- Feeling incompetent and slow?

If the answer is:

“I actually like talking to patients, especially when there’s time and I’m not rushed; I just hate the pace and the constant inbox of tasks” — that’s burnout + system issues, not necessarily “wrong career.”

If the answer is:

“I feel relieved when I get to stay away from patients. I don’t like the conversations, the emotional labor, the unpredictability. I only feel engaged when I’m in research mode” — that’s a more fundamental preference.

Now add a bit of structure. For the next 2–3 weeks:

- After each day, rate on a 1–10 scale:

- Clinical satisfaction today

- Clinical exhaustion today

- Research satisfaction (if you did any)

- General dread about going back tomorrow

Track it. Do not trust your memory. Burnout colors everything.

You’re looking for patterns. Not one bad week on a malignant service.

Step 3: Test Whether You Actually Love Research Enough

Here’s the trap I’ve seen over and over:

Students burn out from clinical rotations and run toward research because it feels cleaner, quieter, and more controllable. That does not mean they truly want a research career. It means the lab looks better than getting paged constantly.

You need to test if you actually love the work of research, not just the relief from wards.

Signs you probably have genuine research drive:

- You’re drawn to methodologic details, not just the “cool topic.”

- You’ve voluntarily read stats or methods textbooks or tutorials outside of what’s required.

- You actually enjoy:

- Troubleshooting methods

- Iterating on hypotheses

- Wrestling with messy data

- You get energy from long, uninterrupted stretches of thinking, writing, or coding.

- You’ve stuck with at least one project beyond the “shiny new idea” phase into the boring cleanup, revision, resubmission phase.

If your “love of research” is mostly:

- “I like that nobody is yelling at me in the lab.”

- “I like that I can go to the bathroom whenever I want.”

- “I like that I can put on headphones and not talk to people.”

That’s more about environment than career fit.

Run a second experiment:

For 4–6 weeks, carve out consistent, real research time:

- 4–8 hours/week of focused, scheduled research (not just “when I have time”).

- Treat it like a second job: regular meetings with your PI, clear goals, deadlines.

At the end of that period, ask:

- Do I look forward to that time, even when I’m tired?

- Am I willing to fight for that time in my schedule?

- If I imagine doing this sort of work 5–10 years from now, does that feel exciting or deadening?

Your honest answers matter more than anyone else’s opinion.

Step 4: Understand Your Actual Options (MD, MD/PhD, PhD)

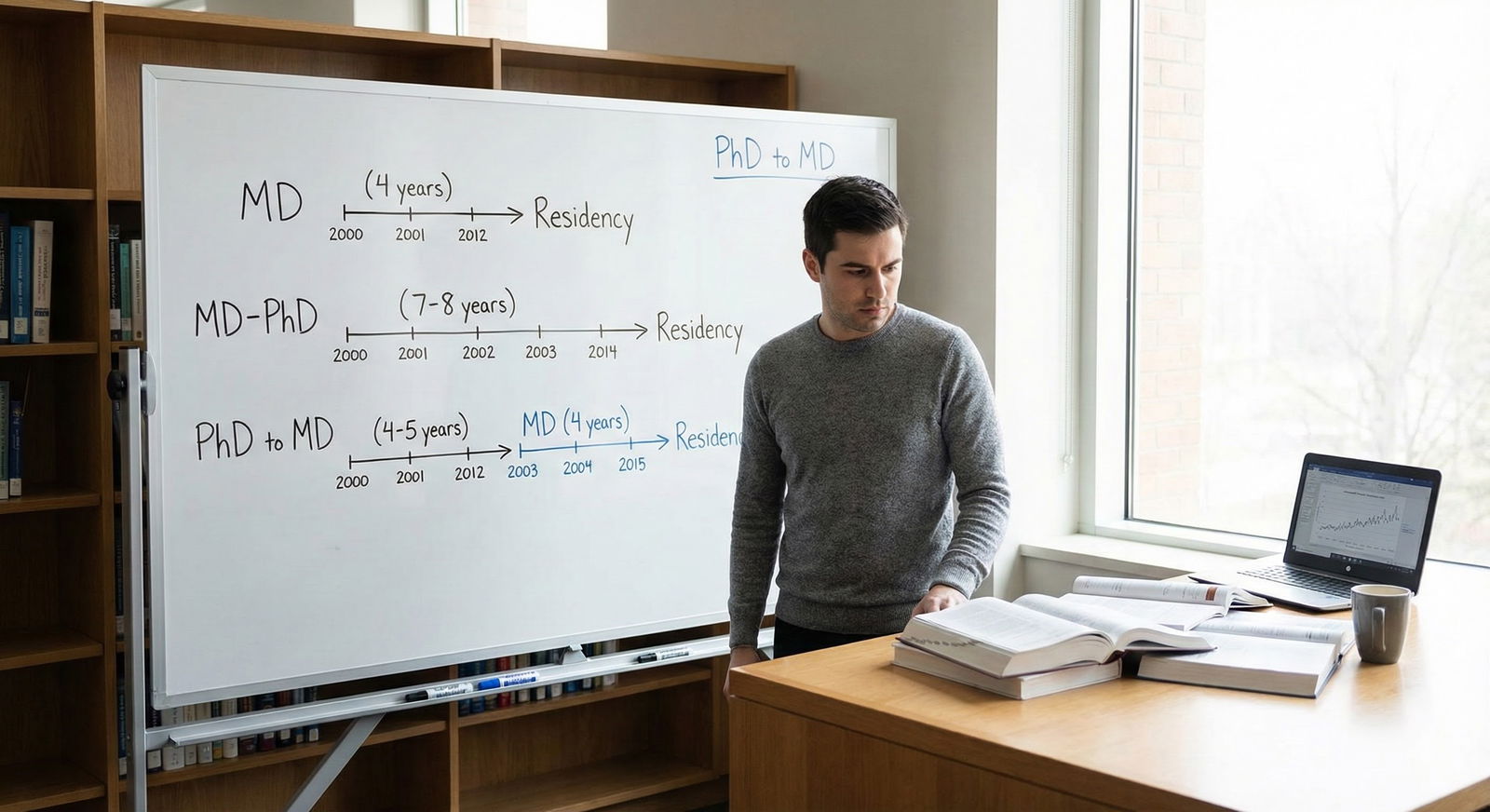

People tend to frame this like a binary: “MD or PhD?” That’s wrong. You actually have a menu of options, each with different tradeoffs.

Here’s the landscape in simple form:

| Path | Clinical Role | Research Intensity | Typical Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD only | Primary | Variable/optional | 4 yrs + residency |

| MD then research fellowship | Primary with protected time | Moderate–high | 4 yrs MD + residency + 1–3 yrs |

| MD/PhD | Mixed | High | 7–9 yrs + residency |

| PhD only | None/limited | Very high | 4–7 yrs PhD + postdoc |

| MD then later PhD | Mixed | Very high | 4 yrs MD + residency ± fellowship + 3–5 yrs |

Let me walk through how these actually play out in real life.

Option A: Stay MD-Only, Build a Research-Heavy Career Later

You finish med school. You match into a residency at a place with a real research culture (think: academic IM, neuro, peds, psych, etc.). You aim for:

- Research track positions

- 20–80% protected research time during or after residency

- A research fellowship or mentored K award later

Who is this good for?

- You still see some value in being a clinician.

- You like research but are not 100% sure you want to give up patient care.

- You don’t want to blow up your current MD trajectory with another degree right now.

- You care about financial stability sooner rather than later.

Reality check: You can absolutely have a research-heavy career with an MD only. I’ve seen MDs with 70–80% research time in academic departments, especially if they’re productive and well-mentored.

Option B: Switch into MD/PhD Now (If Timing Allows)

If you’re preclin or early M2 and your school has a pathway to join the MD/PhD program, this might be on the table. Later than that, it gets messy but sometimes still possible.

MD/PhD makes sense if:

- You genuinely want to split your career between bench/clinical research and some patient care.

- You’re okay with being in training for a long time (7–9 years before residency).

- You want formal preparation in research methods, not just picking it up informally.

Downside: If your current burnout is really about hating clinics long-term, MD/PhD might just kick the can down the road while you grind through extra years of training.

Option C: Finish MD, Then Do a PhD

This is more common than most students realize, especially in certain fields (psychiatry, neurology, epidemiology, health services research).

Path looks like:

- Finish MD

- Do residency (maybe in a lighter clinical specialty)

- THEN pursue a PhD in epidemiology, bioinformatics, health policy, etc.

Good if:

- You want to be a serious researcher with deep expertise.

- You want the “MD lens” but do not necessarily want heavy clinical volume long-term.

- You like the idea of later career flexibility between clinical and academic roles.

Downside: It’s long. And you have to survive residency first.

Option D: Stop MD, Move to PhD Only

This is the nuclear option everyone whispers about but rarely talks through properly.

When does this actually make sense?

- You are very sure you do not want a clinical career.

- You consistently dislike direct patient care, even in better-run environments.

- You feel energized by the idea of a full-time research career.

- You can live with: lower lifetime earnings, academic politics, funding stress, and the fact that faculty jobs are not guaranteed.

You’re trading clinical security for alignment with your actual interests. That can be a very rational move. But you should not decide this based on one malign rotation and a PI who’s nice to you.

| Category | Clinical (%) | Research (%) | Admin/Teaching (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD only academic | 70 | 20 | 10 |

| MD/PhD faculty | 40 | 50 | 10 |

| PhD only faculty | 10 | 80 | 10 |

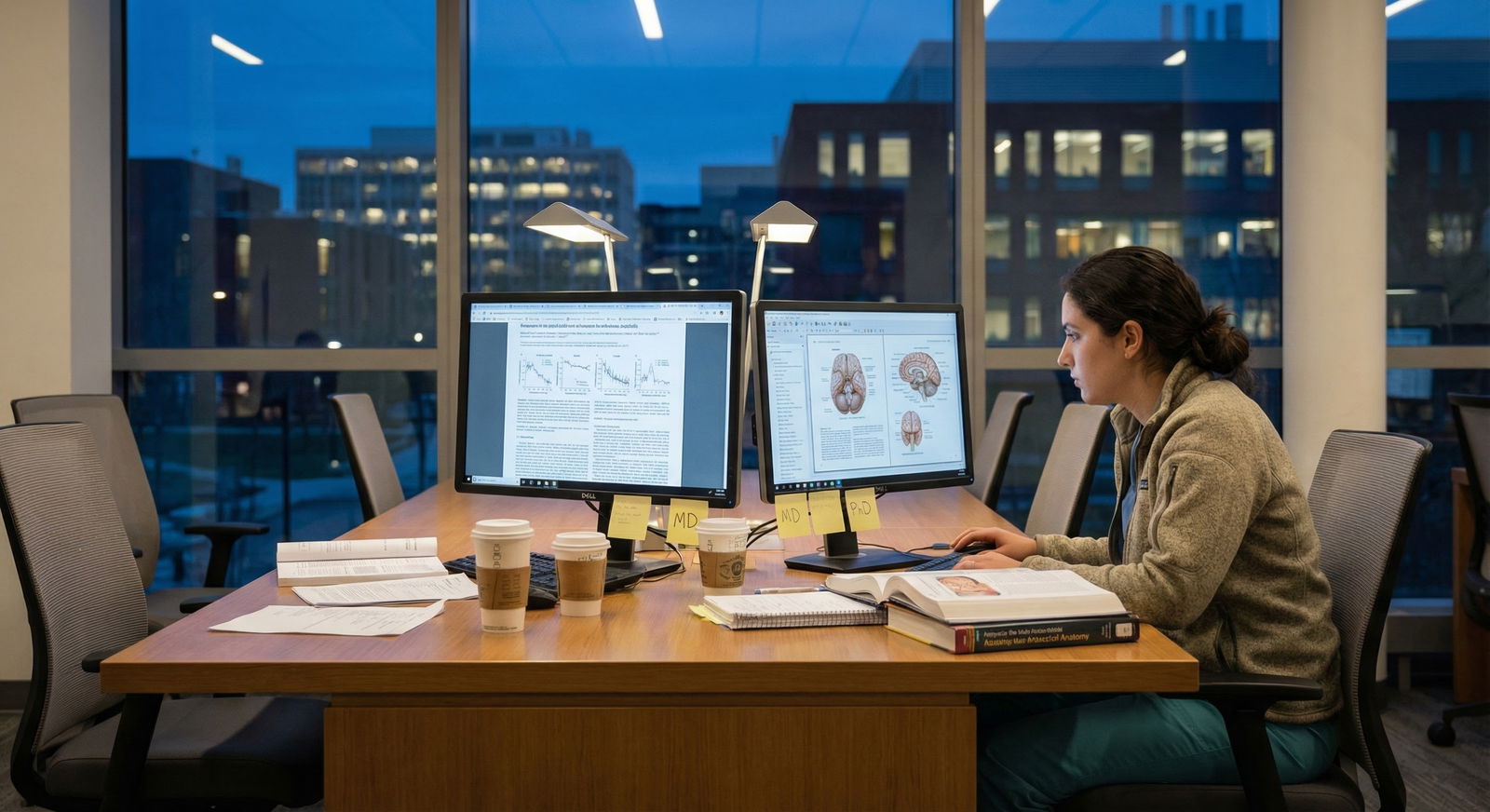

Step 5: Reality-Check Your Future Day-to-Day

Stop thinking in degrees. Think in Tuesday at 10:30 a.m. What are you actually doing?

Picture three different future you’s:

MD Clinician-Researcher (academic IM attending)

- 10:30 a.m. Monday: Rounding with residents.

- 10:30 a.m. Tuesday: Zoom meeting about your R01, arguing about sample size and endpoints.

- 10:30 a.m. Wednesday: Clinic.

- 10:30 a.m. Thursday: Writing a revision letter for a manuscript.

- 10:30 a.m. Friday: Department meeting.

MD/PhD Translational Scientist

- 10:30 a.m. Monday: Reviewing data with postdoc and RA.

- 10:30 a.m. Tuesday: One half-day clinic or tumor board.

- Rest of the week: Grant writing, manuscript revisions, troubleshooting experiments, mentoring.

PhD-Only Scientist

- 10:30 a.m. every weekday: Some mix of:

- Data analysis

- Writing

- Lab meetings

- Teaching

- Trying to keep funding

- 10:30 a.m. every weekday: Some mix of:

Now ask: which of these feels like a life you could tolerate for a decade? Which one actually sounds appealing, not just “less bad than third-year surgery”?

Write this down somewhere private. Your brain will try to rationalize later.

Step 6: Build an Inner Circle (But Filter Their Advice)

You need input from humans who’ve actually lived these paths. But you also need to discount their biases.

Talk to:

- A pure clinician in a field you might consider.

- A clinician-researcher (with >50% research time).

- Someone with MD/PhD.

- A PhD-only researcher in a field you’re drawn to (epi, basic science, informatics, whatever you actually like).

In each conversation, ask concrete questions:

- “What did your last normal week look like, in hours and activities?”

- “If you lost all your grant funding tomorrow, what would happen to your job?”

- “When do you actually feel happiest in your work?”

- “What’s the worst part of your job that students don’t see?”

Then, filter:

- Pure clinicians often underestimate how fulfilling research can be.

- Pure PhDs often underestimate how demoralizing clinical systems can be.

- MD/PhDs sometimes glorify their path because they paid so much for it in time.

You’re not looking for anyone to decide for you. You’re building a dataset of realities, not vibes.

Step 7: Short-Term: How to Survive While You Decide

You still have to get through this week. And probably this year. So let’s stabilize things.

Here are practical, non-fluffy steps:

Trim all nonessential extras.

Right now, your primary job: pass rotations, keep research alive, protect your brain. This is not the semester to lead three student orgs.Create one “research protected block” per week.

Even if it’s just 3 hours Sunday morning. Use it to remind yourself: “I’m good at something. I enjoy something.”Clinical “minimum viable performance.”

Stop trying to be a superhero on service. Hit:- Show up on time

- Know your patients cold

- Write competent notes

- Be teachable

That’s enough. You don’t need to be everyone’s favorite student.

One small step toward clarity each week.

Examples:- Week 1: Track satisfaction/exhaustion scores daily.

- Week 2: Schedule a meeting with a clinician-researcher.

- Week 3: Shadow a researcher or go to lab meeting.

- Week 4: Talk to student affairs about what changing paths would actually involve.

Progress is progress, even in tiny units.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Burned out on clinics |

| Step 2 | Track clinical vs research satisfaction |

| Step 3 | Deep research interest? |

| Step 4 | Explore MD research careers |

| Step 5 | Focus on clinical fit and wellness |

| Step 6 | Explore PhD or MD PhD paths |

| Step 7 | Address burnout and environment |

| Step 8 | Talk with mentors in each path |

| Step 9 | Trial experiences and decide long term path |

| Step 10 | Ever enjoy patient care? |

| Step 11 | Research consistently higher joy? |

Step 8: When (and How) to Consider Actually Leaving MD

You’re probably wondering this, so let’s address it head-on.

Leaving MD is not a moral failure. It is a career pivot. But it’s a big one, and you should treat it like surgery, not a quick outpatient procedure.

Before seriously considering withdrawal, you should:

Have at least two long conversations:

- One with someone who left MD for research or something else.

- One with someone who was extremely burned out but stayed and later redesigned their career (e.g., moved into research-heavy role).

Get factual info from your school:

- Financial implications (loans, repayment timelines).

- Whether you can take a leave of absence to think instead of quitting outright.

- Whether there are formal MD/PhD transfer or research pathways.

Run a thought experiment:

- Imagine you magically had your MD tomorrow, with no more training required.

- Would you use it?

- Or would it just be a very expensive trophy while you do research full-time anyway?

- Imagine you magically had your MD tomorrow, with no more training required.

If you’d essentially walk away from clinical work even with a free MD, that tells you something.

If instead you think, “I want the MD so I can at least have the option of clinical work, but I want to minimize it,” you’re probably in MD + research territory, not PhD-only territory.

Step 9: Concrete Action Plans by Scenario

Let me give you three common patterns I see, and what I’d tell each student to actually do in the next 6–12 months.

Scenario 1: “I’m fried but still see some value in clinical work”

You’re exhausted, but occasionally you connect with a patient and remember why you started this. Research feels like a refuge, but you could imagine a career where you do both.

Your plan:

- Commit to finishing MD.

- Shift your goal from “survive” to “finish MD while deliberately collecting data for my future research-heavy career.”

- Seek:

- Academic departments where research is expected.

- Residency programs with protected research time.

- A mentor who’s a real clinician-researcher, not a token one.

You’re probably a good fit for MD → research-heavy residency → potential K award / 50–80% research attending role.

Scenario 2: “I really do not like patient care, but I love research mechanics”

You consistently dislike being in exam rooms. You drag yourself to rounds. But you light up talking about study design, code, or mechanistic pathways.

Your plan:

Give yourself permission to take this seriously. This is not laziness. It’s career mismatch.

Map three concrete paths:

- Finish MD → residency in low-burnout specialty → eventually mostly research.

- Finish MD → after some clinical training, do PhD in your chosen research field.

- Pause or leave MD → go straight into PhD or research role (after carefully evaluating finances and visa issues if relevant).

Spend the next 3–6 months:

- Talking to at least two people living each of those paths.

- Visiting at least one lab or research group where you could realistically work.

- Getting brutally clear about your non-negotiables: geography? finances? family?

You may still decide to finish MD for optionality. Or not. But it’ll be a decision, not an escape.

Scenario 3: “I feel dead inside everywhere, including research”

You’re not just burned out on clinics. You’re burned out, period. Research used to be fun; now even opening your project file feels heavy.

Your plan is not “decide your entire life path right now.” Your plan is:

- Get your basic health and mental health handled. Sleep, therapy, maybe meds. Yes, I’m serious.

- Lower the bar:

- Meet minimum standards clinically.

- Put research in “maintenance mode” (occasional meetings, no big new commitments).

- Push big career decisions 3–6 months down the road, when your brain isn’t on fire.

I’ve watched too many students in this state blow up their careers and then realize later they actually did like medicine or research, they just needed to not be drowning.

Step 10: What To Do This Month

To keep this from staying abstract, here’s a one-month punch list:

Week 1:

- Start the daily 1–10 rating of clinical vs research satisfaction/exhaustion.

- Block off one 3–4 hour research session in your calendar.

Week 2:

- Email one clinician-researcher and ask for a 20–30 minute chat.

- Ask your PI about people in their network who’ve done MD/PhD/PhD-only in your area.

Week 3:

- Attend one research seminar or lab meeting outside your immediate project.

- Talk with one upper-year student or resident who is research-oriented and relatively sane.

Week 4:

- Book a confidential meeting with student affairs or an advisor you trust and ask:

- “If I wanted to pivot more toward research, what options have previous students here actually taken?”

- “Has anyone ever transferred into MD/PhD? Left for PhD? How did that go in reality?”

By the end of the month, you won’t have fixed your life. But you’ll be out of the “vague dread and fantasy” stage and into concrete planning.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. Am I just weak or lazy if I hate clinics but like research?

No. Clinical medicine and research are two very different jobs that happen to live under the same institutional roof. Not everyone is wired to enjoy intense interpersonal work, constant interruptions, and emotional labor. Preferring deep-focus, analytic work is normal. The key is being honest about your temperament and designing a career that fits it, rather than forcing yourself into a mold and then resenting everyone.

2. Will I ruin my career if I don’t decide MD vs PhD right now?

You have more flexibility than you think. Many people figure this out later: they finish MD, then lean heavily into research; or they start clinical training and then pursue a PhD or advanced research training; or they move from PhD to clinical-adjacent work. Yes, some choices close certain doors, but very few are completely final at your stage. The only thing that reliably ruins careers is impulsive, poorly informed decisions made at peak burnout.

3. Do residency programs actually care if I’ve done serious research as a student?

Academic programs absolutely do. If you’re leaning toward a research-heavy path, building a real track record now (meaning: sustained projects, not just your name on a poster you barely remember) will help you get into the kind of residency where research time and mentorship exist. Community programs may care less, but you’re not aiming for them if you want a research career. Your student research doesn’t need to be world-changing; it just needs to demonstrate that you can see projects through.

4. What if I finish MD and then never use it because I go full-time research? Is that a waste?

It’s only a waste if you define “waste” as “time spent on something I no longer do 100% of the time.” Plenty of PhD-only faculty never “use” half their training either. If the MD gives you a deep understanding of disease, patients, and clinical reality that shapes the questions you ask as a researcher, it’s not wasted. The real question is opportunity cost: could those years have been better spent in a pure research trajectory for you? That’s where you have to weigh your goals, finances, and how certain you are that you never want to practice.

You’re in a rough stretch. Clinics are draining, research is the only thing that feels alive, and everyone around you seems to just “love patient care” like it’s their favorite hobby. Ignore the noise. Track your own data, test your interest in research seriously, and start having targeted conversations with people who actually live the careers you’re imagining.

Once you’ve done that groundwork, you’ll be in a position not just to survive medical school, but to choose—on purpose—what kind of physician, scientist, or something-in-between you want to become. And when you get closer to residency applications and job talks, the decisions you’re making now will pay off in options. But that’s a story for another stage.