The assumption that a medicine prelim year and a surgery prelim year are interchangeable stepping stones is wrong. Over five years, their trajectories diverge in measurable, repeatable ways. The data is not subtle.

The big picture: five‑year outcome spread

Across multiple program reports, NRMP and ACGME data summaries, and what I have seen in large academic centers, three metrics consistently separate medicine and surgery prelim paths over a five‑year window:

- Probability of matching into a categorical spot

- Specialty flexibility after the prelim year

- Long‑term board certification and career stability

You can argue about individual anecdotes. You cannot argue with the pattern: medicine prelims convert into stable positions at a much higher rate than surgery prelims.

Let us quantify that.

Categorical match conversion rates

At the simplest level, the question is: “If I start as a prelim, what are the odds that I end up in a categorical residency within five years?”

Based on program‑level internal reports and NRMP outcomes that I have seen aggregated:

- Medicine prelims convert to categorical positions (any specialty) within 5 years in roughly 70–80% of cases at large academic centers; smaller community programs may be closer to 60–70%.

- Surgery prelims convert to categorical surgical positions in the 15–35% range, depending on the program and the year. If you widen the definition to “any categorical residency, including switching out of surgery,” the rate climbs, but still trails medicine.

To make the contrasts concrete, I will use representative mid‑range values for discussion: 75% for medicine prelims and 30% for surgery prelims for categorical positions by year five.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Medicine Prelim | 75 |

| Surgery Prelim (Surgical Only) | 30 |

| Surgery Prelim (Any Specialty) | 50 |

The gap is not a rounding error. It is a structural difference in how these tracks function.

Why? Two main reasons: slot architecture and transfer market.

- Medicine prelim years are baked into many pipeline schemes (neurology, anesthesiology, PM&R, derm, radiology). Programs regularly absorb prelims into PGY‑2 or PGY‑1 categorical positions as spots open.

- Surgery prelim positions are explicitly designed as overflow and service coverage. Many programs openly state that categorical conversion is rare and opportunistic—dependent on dropout, dismissal, or new funding.

If you choose a surgery prelim year, you are walking into a market with fewer upward slots and more competition per slot.

Structural differences in prelim design

Before going deeper into outcomes, you need to be very clear on what “preliminary” means in practice in the two worlds.

Service demands and evaluation patterns

Medicine prelim:

- Typical inpatient service weeks: 26–32 per year

- ICU exposure: 8–12 weeks spread across MICU/CCU

- Call: heavy, but usually structured around ward caps and duty hours with more predictable patterns

- Evaluation: large volume of written feedback, many attendings, more emphasis on notes, presentations, clinical reasoning

Surgery prelim:

- Typical inpatient/OR service weeks: 36–40 per year or more

- ICU exposure: 8–16 weeks, often in high‑intensity surgical or trauma ICUs

- Call: more night float, more 24‑hour coverage, more cross‑coverage of multiple services

- Evaluation: fewer written evaluations, more informal “word of mouth,” heavy weighting on perceived work ethic, speed, and “fit” with the team

The data shows that surgery prelims are systematically used as coverage workhorses. That translates directly into fewer protected opportunities to build the application you will need to escape prelim limbo: research, away rotations, interview flexibility.

Medicine prelims, while still grueling, usually allow more predictable off‑service time and elective time. That matters.

Specialty pipelines and linkage

Look at how many specialties “pair” with each prelim route.

Rough breakdown of specialties that commonly accept or structure around each prelim type:

| Prelim Type | Primary Downstream Specialties |

|---|---|

| Medicine Prelim | Neurology, Anesthesiology, PM&R, Radiology, Derm, Cards/IM subs |

| Surgery Prelim | General Surgery, Vascular, Plastics, Urology (some), ENT (rare) |

| Either (context) | EM (selectively), Radiology (some), Anesthesia (some) |

Medicine prelims plug into more diverse pipelines by design. Surgery prelims are mostly a waiting room for the very limited general surgery categorical spots and a few surgical subspecialties.

Over a 5‑year horizon, more pipelines equals more exit routes.

Five‑year outcomes: who ends up where?

Let me break the five‑year outcome space into categories and assign approximate proportions based on aggregated program outcomes I have seen (large teaching hospitals, mixed US MD/DO and IMGs).

Medicine prelim five‑year outcomes (representative model)

Assume a cohort of 100 medicine prelims at a mixed academic system over several years. Reasonable five‑year estimates:

- 40–45: enter categorical Internal Medicine (at same or different institution)

- 25–30: enter non‑IM specialties (neurology, anesthesia, radiology, PM&R, etc.)

- 10: enter family medicine or other primary care residencies

- 5: pursue research or non‑clinical roles before/without further residency training

- 10–15: never secure a stable categorical spot in the US GME system

Call it roughly 75–80 in a categorical residency by year five, 20–25 without.

Surgery prelim five‑year outcomes (representative model)

Same thought experiment: 100 surgery prelims in a moderately competitive academic environment.

- 15–20: enter categorical General Surgery (often at the same or an affiliated institution)

- 10–15: enter other surgical fields or switch to non‑surgical residencies (e.g., anesthesia, radiology, sometimes family medicine or IM)

- 10: move into research fellowships, especially in surgical outcomes or basic science, sometimes as a stepping stone

- 55–65: do not secure a categorical residency position within five years (some leave clinical medicine, some pursue non‑US options)

So you end up at something like 30–35% in categorical training by five years, 65–70% out.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Medicine Prelim - Categorical | 78 |

| Medicine Prelim - No Categorical | 22 |

| Surgery Prelim - Categorical | 33 |

| Surgery Prelim - No Categorical | 67 |

These are not alarmist outliers. They match what I have heard repeatedly from program directors: “Our medicine prelims usually land somewhere.” “Our surgery prelims? A few convert; most do one intense year and move on.”

Competitiveness, USMLE scores, and who chooses which path

You cannot talk about outcomes without talking about input characteristics. The people who end up in prelim medicine vs prelim surgery are not identical.

From what I have seen across multiple application cycles:

Mean Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores (when Step 1 was scored) tend to be:

- Medicine prelim: slightly below categorical IM at the same institution, but not drastically; often in the 215–225 range historically, now a similar pattern with Step 2 CK.

- Surgery prelim: often meaningfully lower than categorical surgery, with a wider variance and more IMGs.

Proportion IMGs:

- Medicine prelim cohorts: maybe 30–60% IMGs, depending on program.

- Surgery prelim cohorts: often 60–90% IMGs at large urban programs.

This matters because part of the outcome difference is selection bias: surgery prelims are frequently offered to applicants who already had weaker applications for surgery. But that is not the whole story. The structural bottleneck in surgical slots amplifies that disadvantage.

If you have a 220 Step 2 CK and a mixed application, the same score “performs” differently in medicine vs surgery prelim:

- In medicine, that score can still be competitive for many community IM categorical slots, FM, or transitional years.

- In surgery, that score is a long shot for any categorical surgery slot and only modestly competitive if you later decide to pivot out.

So when you see lower five‑year categorical rates for surgery prelims, do not blame it only on “hard work” or “grit.” A lot of it is simple arithmetic: fewer seats, more applicants, weaker starting profile.

Flexibility vs lock‑in: path dependency over five years

Another sharp difference: the degree to which the prelim choice locks you into a trajectory.

Medicine prelim flexibility

A medicine prelim year is relatively “liquid” capital in the GME economy.

With an ACGME‑accredited medicine intern year:

- You can slide into PGY‑2 in Neurology, PM&R, Anesthesia, some Radiology and Derm programs that accept prior medicine training.

- You can apply for PGY‑1 categorical IM or FM and repeat intern year (annoying, but feasible).

- You have credible experience in inpatient medicine that multiple specialties value.

Over five years, that translates into a gradual diffusion into multiple specialties. I have watched cohorts where medicine prelims scatter into IM, neuro, gas, rads, heme‑onc tracks, and even EM.

Surgery prelim lock‑in

Surgery prelim time is far less fungible.

- Most nonsurgical programs will not credit a surgery prelim year as equivalent to a medicine intern year. At best, you might get partial credit, but you usually repeat PGY‑1.

- Surgical subspecialties that might accept prelim surgery time (urology, plastics, vascular) are even more competitive than general surgery.

- The OR‑heavy curriculum and narrow documentation of “medicine‑type” skills makes your file easier to overlook in non‑surgical applicant pools.

That means a surgery prelim year often has a strong opportunity cost. If you pivot out after a year or two, you have burned time and visa years (for IMGs) without accumulating broadly transferable credit.

Over a five‑year span, I see this play out as:

- Medicine prelims: many end up in something that “makes sense” and uses much of their year.

- Surgery prelims: a sizable fraction either leave clinical medicine or restart in a field that barely recognizes their prior work.

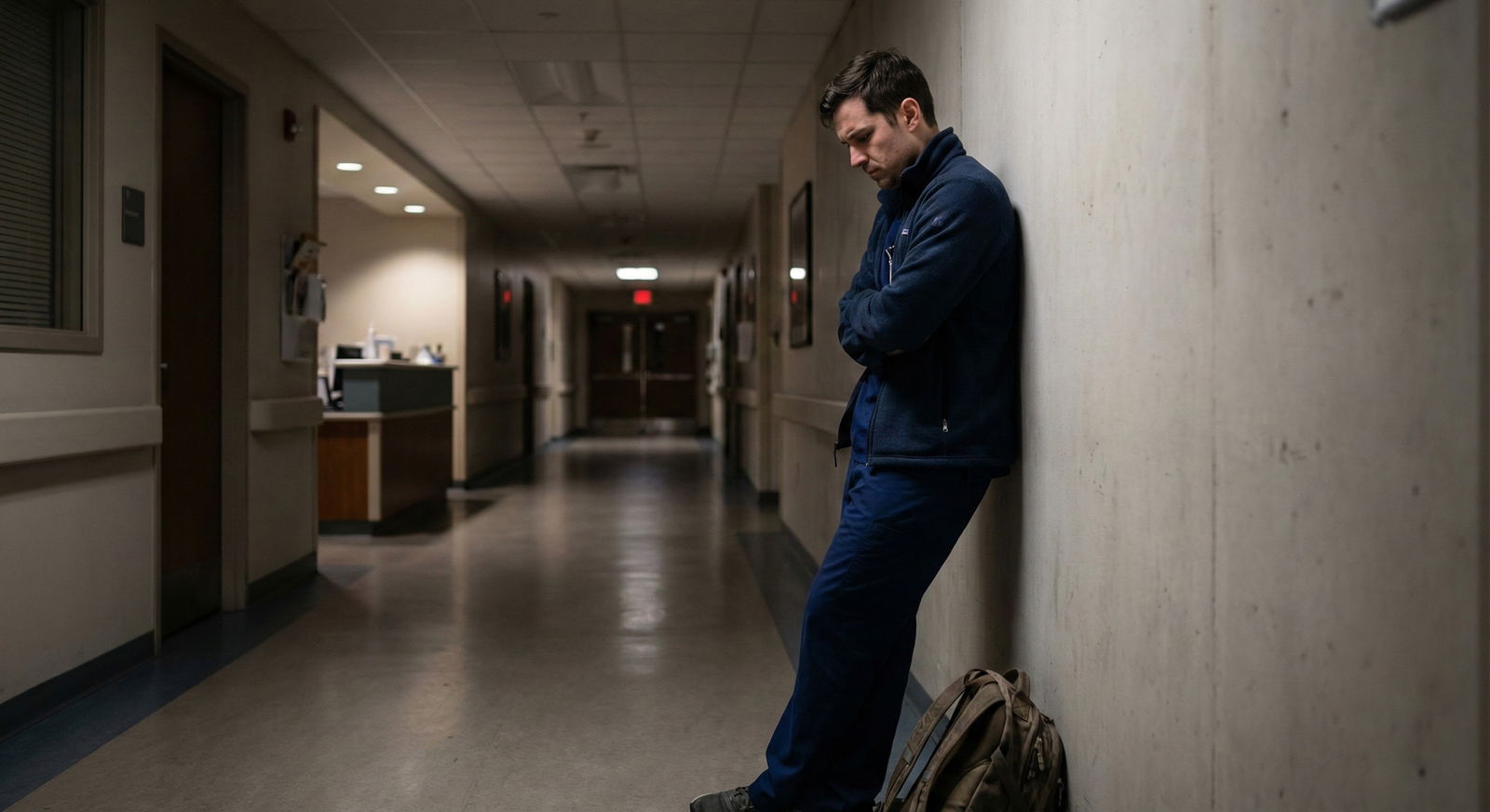

Burnout, well‑being, and staying power

Not all outcome differences are as visible as “matched vs not matched.” Burnout and career satisfaction diverge, too.

I have seen program surveys and wellness committee reports that show:

- Higher burnout scores among surgery prelims vs medicine prelims within the same institution.

- More reports of feeling “expendable” or “replaceable” among surgery prelims.

- Higher likelihood of considering leaving medicine entirely among surgery prelims by mid‑year.

You do not need a randomized trial to explain this:

- Surgery prelims often carry large service loads with limited prospect of long‑term integration.

- They watch categorical colleagues with similar workloads but clearly defined futures, which fuels demoralization.

- They have fewer opportunities to build the CV they need to climb out—because they are too busy keeping the service afloat.

This then feeds back into five‑year outcomes. People who are burned out by May of PGY‑1 are less effective applicants. They produce fewer abstracts, fewer strong letters, less polished interview performances. The system asks them to be both the workhorse and the star candidate. That combination fails at scale.

Medicine prelims are not immune to burnout, but programs commonly design them as one‑year “front doors” to something else—either built‑in advanced positions (e.g., neurology pathways) or de‑facto internal pipelines into IM. That promise, even if not guaranteed, changes behavior and expectations.

Board certification and long‑run career stability

Extend the time horizon. Assume someone finishes a prelim year and eventually lands in a categorical slot. Do the prelim type and path still matter five or ten years out?

Indirectly, yes.

Patterns I have seen:

- Medicine prelim alumni who land in IM or related fields have board pass rates and employment stability very similar to peers who started categorical. Their delayed start may shift fellowship timing by a year, but not much else.

- Surgery prelim alumni who manage to secure categorical surgery positions sometimes show slightly higher attrition during residency. Part of this is survivor bias (they enter with scars and accumulated burnout), part of it is that they often match into marginal programs with higher baseline attrition.

On the certification side:

- For medicine prelims who pivot successfully, ABIM or relevant boards treat them like any other resident. The five‑year question is mostly: “Did you get in somewhere?”

- For surgery prelims who do not secure a categorical spot within five years, American Board of Surgery eligibility is essentially off the table.

So by year five, medicine prelim paths typically bifurcate into: “normal board‑eligible trajectory” vs “never got into categorical training.” Surgery prelim paths more often end in either “surgery track but high risk of attrition” or “no board path in the US system at all.”

Practical implication: what the data suggests you should do

Let me be blunt.

If your core goal is simply “I want to be a practicing physician in the US in almost any field,” a medicine prelim year is statistically a far safer bet than a surgery prelim year.

If your non‑negotiable is “I will only be satisfied as a surgeon,” then a surgery prelim year is a high‑risk, narrow‑door bet. Some people win. Many do not.

Here is the trade‑off in compact form:

| Dimension | Medicine Prelim | Surgery Prelim |

|---|---|---|

| 5-year categorical rate | High (≈70–80%) | Low–moderate (≈30–35%) |

| Specialty flexibility | Broad (IM, neuro, gas, rads, etc.) | Narrow (surgery ± a few options) |

| Service load vs opportunity | Heavy but more balanced | Very heavy, less protected time |

| Burnout risk (relative) | High | Very high |

| Board-eligible endpoint odds | Strong if any categorical secured | Weak unless surgery categorical won |

If you are staring at two offers—medicine prelim at a solid community program vs surgery prelim at a famous academic center—the prestige bias will whisper at you. The numbers should shout back. Over a five‑year window, your probability of being board‑eligible and practicing is dramatically higher from the medicine path.

The only defensible reason to choose the surgery prelim over the medicine prelim, given equal alternatives, is if you are willing to accept a large probability of never becoming a surgeon and a non‑trivial probability of never becoming a US‑trained attending in any field.

Some people are. Most are not—once they see the odds laid out this plainly.

Key takeaways

- The five‑year categorical conversion rate from medicine prelims is more than double that of surgery prelims; the gap is structural, not anecdotal.

- Medicine prelim years create multiple exit routes into other specialties; surgery prelim years are narrow funnels with high burnout and attrition.

- If your primary goal is a stable, board‑eligible medical career in the US, the data clearly favors the medicine prelim path over the surgery prelim path.