The default advice to “never delay your application year” is lazy. Sometimes taking a year to finish a big research project is exactly the right move. Other times it’s a trap that does nothing but cost you time and money. You need a framework, not slogans.

Here’s the answer you’re actually looking for: delaying one year for research is worth it only if it significantly changes how competitive you are in your specific specialty and you can articulate that upside clearly on paper and in interviews. Anything short of that is usually not worth a full extra year of your life.

Let’s break this down like an attending who’s already heard every excuse and every success story.

Step 1: Get Clear on Your Current Competitiveness

Before you even talk about the research project, you need an honest assessment of where you stand right now as an applicant.

Ask yourself, for the specialty you’re targeting:

- Are your scores in range or below?

- Is your clinical performance strong, average, or shaky?

- Do you have meaningful letters coming?

- Any red flags? (failures, LOAs, professionalism issues)

- How strong is your existing research profile relative to that field?

If you don’t know, talk to people who do:

- Your home program PD or APD in that specialty

- An honest mentor who regularly advises applicants

- Recent grads who matched into that field

You want a blunt answer to: “If I apply this cycle, what tier of programs am I realistically competitive for?”

If the consensus is:

- “You’ll match, but probably not at the most competitive places,” that’s different from

- “You might not match at all in this specialty.”

The more your baseline is “at serious risk of not matching,” the more a research year might be justified—but only if the project actually fixes the underlying problem.

Step 2: Understand How Much Research Your Specialty Actually Cares About

This is where people often lie to themselves.

Some specialties are obsessed with research; others barely care as long as you are not totally blank. Here’s a rough reality check:

| Specialty | Research Weight* |

|---|---|

| Dermatology | Very High |

| Plastic Surgery | Very High |

| Neurosurgery | Very High |

| Radiation Oncology | High |

| ENT (Otolaryngology) | High |

| Orthopedics | Moderate–High |

| Internal Medicine | Moderate |

| Pediatrics | Low–Moderate |

| Family Medicine | Low |

*Not an official scale—this is how PDs and faculty actually talk about it.

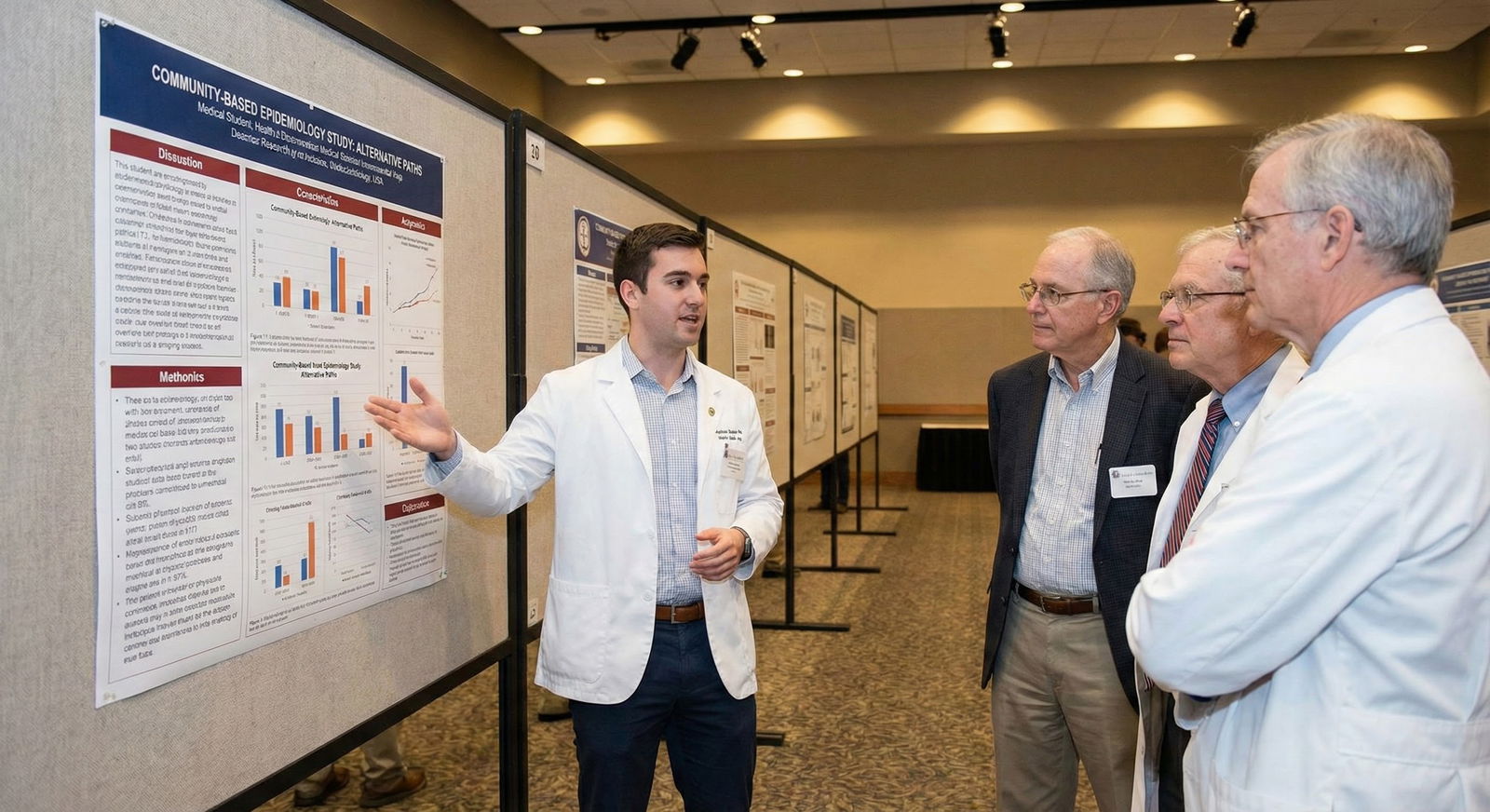

In derm, plastics, neurosurgery, some ENT and ortho programs: a research year is common, sometimes almost expected, especially if you’re not a superstar on Step 2 or your home institution is weak in that specialty.

In IM, peds, FM, psych: an extra year to finish one big project rarely moves the needle enough to justify delaying an entire application cycle. You’d almost always be better off applying now, unless your record is truly a mess.

So you need to answer:

In my target specialty, does a strong research portfolio actually unlock programs I currently cannot touch?

If the honest answer is “not really,” then delaying a year just for research is probably a bad trade.

Step 3: Evaluate This Specific Research Project (Not “Research in General”)

People talk about “doing a research year” like it’s all the same. It’s not. The details matter a lot.

You should only consider delaying for a research year if most of these are true:

The project is real, defined, and already started.

Not vague “we might start a big study on X.” You want: IRB submitted or approved, dataset accessible, clear plan.You have a committed PI with a track record of publishing and supporting residents.

I want to hear things like: “This PI has put 4 students into derm in the last 3 years,” not “He’s busy but said I could help with data.”You can reasonably finish and submit something before or early in your application year.

Ideally:- 1–2 first- or co-first-author manuscripts submitted or accepted

- Several abstracts/posters at recognizable meetings

- Real, defensible results you can discuss

The work is in or very close to your chosen specialty.

Hem-onc basic science doesn’t help much for ortho. Derm case series doesn’t help for neurosurgery. Programs care more when the research connects to the field you’re applying to.There’s visible institutional or departmental support.

Named research fellowship, formal position, stipend, structured mentorship, meeting attendance, etc.

Here’s a useful rule:

If you cannot, in two sentences, describe exactly what you’ll produce from this year—“I’ll be first author on X, co-author on Y, with at least two national presentations in Z field”—then you’re not ready to delay for it.

Step 4: Compare the Two Futures Side by Side

This is where you need to get brutally concrete.

Option A – Apply on time (no delay).

Option B – Delay one year to finish the big research project and then apply.

What changes on your ERAS between A and B?

Consider:

- Step 2 score: Will it be any different? (Usually not tied to the research decision.)

- Clinical grades: Already set.

- Research:

- Right now: “2 posters, 1 middle-author paper, some small QI.”

- After the year: “2–3 first-author papers submitted or accepted, 3–5 more co-author papers, multiple national presentations, a clear research niche in [specialty].”

- Letters:

- Right now: standard “hard worker, pleasant to work with” letters.

- After the year: a heavy-hitting letter from your research PI who is known in the field.

You want something like this:

| Factor | Apply Now | After Research Year |

|---|---|---|

| Research Output | 1–2 minor projects | 2+ first-author, multiple co-authors |

| Specialty Fit | General, unfocused | Clear niche in target specialty |

| Letter Strength | Standard student letters | Strong PI letter + existing letters |

| Program Tier | Mid/low, some risk | Higher tier + improved match odds |

If the only difference you can honestly project is “maybe 1 paper from this big project” and everything else stays roughly the same, that is not worth a lost year unless you are targeting the very most competitive specialties and starting from behind.

Step 5: Financial, Personal, and Burnout Reality Check

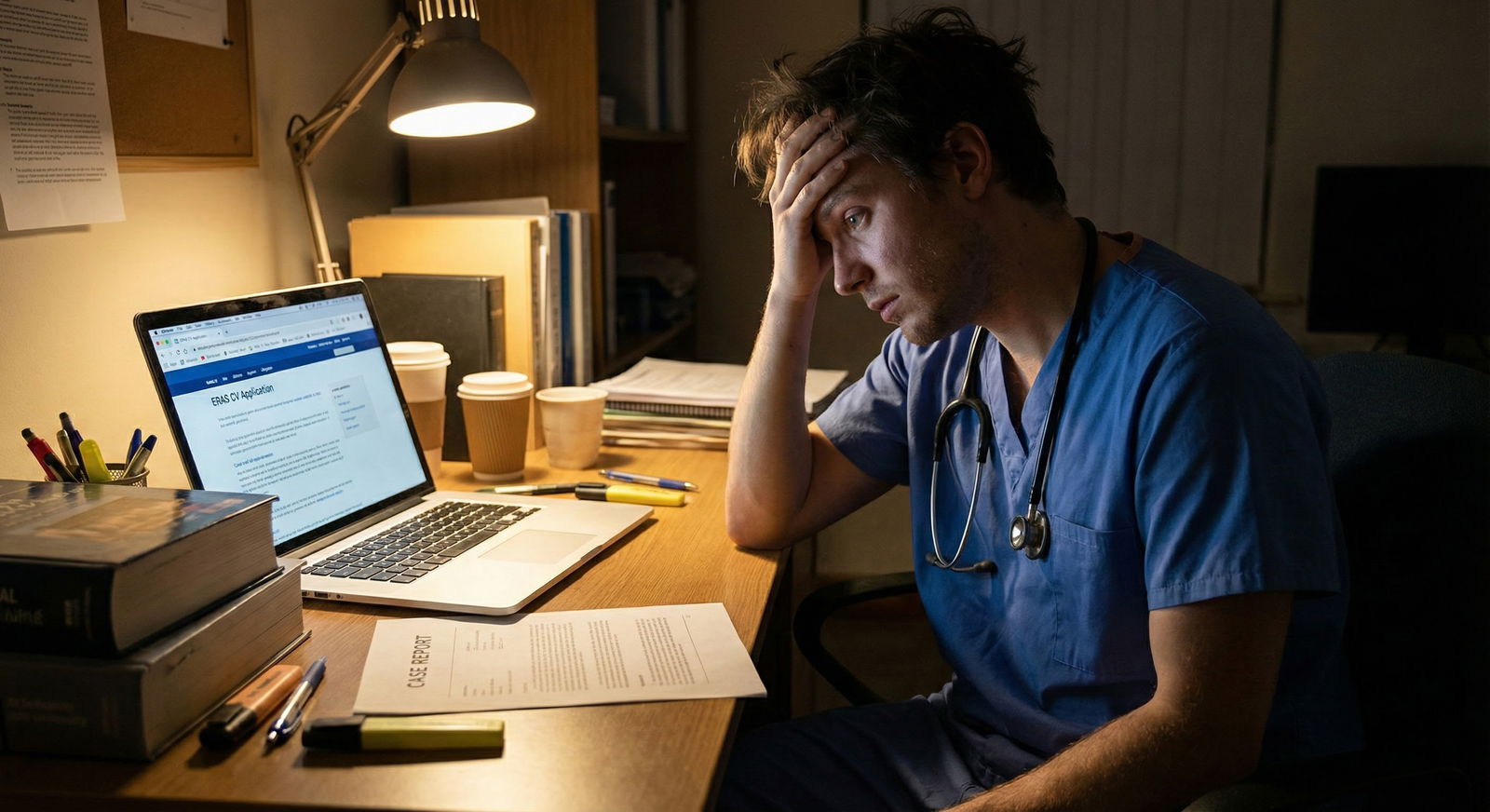

You’re not a robot. A research year isn’t just bullet points on ERAS; it’s your actual life.

You must answer:

Money

- Will you be paid? How much?

- Can you afford another year of not being a resident?

- Will this add more debt?

Visa / timing issues (if IMG or on a visa)

A gap year can complicate things unless properly explained and structured.Burnout

Are you already exhausted and dreaming of moving on, or do you genuinely have fuel in the tank for one intense year of research?Life priorities

Another year means delaying attending salary, delaying big life steps, delaying everything. For some people, that cost is minor; for others, it’s huge.

Do not romanticize the “research year.” A lot of them look like:

- Data cleaning at 11 p.m.

- Endless waiting on co-authors

- Projects that die in committee

- A PI who vanishes when it’s time to write

If you sign up for that, there needs to be serious upside.

Step 6: How Program Directors Actually View a Research Year

Here’s the unfiltered version of what I’ve heard in PD conversations:

Good reaction (for competitive specialties):

- “They took a legit research fellowship year with Dr. X at [strong institution]. Got several first-author pubs. Shows commitment and productivity. That helps.”

Neutral reaction:

- “They did ‘research’ for a year, but output is thin. Seems more like they just didn’t want to apply earlier. Doesn’t hurt much, but doesn’t help either.”

Bad reaction:

- “Gap year with vague research and no clear results. Why? What were they doing? Any issues we’re not seeing?”

So if you delay:

You must be able to clearly say, on paper and in person:

- Why you took the year

- What you did

- What concrete outcomes came from it

- How it changed your trajectory and clarified your fit for the specialty

If that story is tight and backed by actual deliverables, many PDs in research-heavy fields will like it. If it’s fuzzy, it raises suspicion.

Step 7: A Simple Decision Framework

Use this as a blunt rule-of-thumb:

You should strongly consider delaying a year if:

- You’re targeting a highly competitive, research-heavy specialty (derm, plastics, neurosurg, ENT, some ortho, rad onc), and

- Your current application has:

- Either modest research

- Or a red flag (low Step 2, weaker school name, no home program)

that research could reasonably offset, and

- You have a specific, structured, mentored research position with a high likelihood of:

- Multiple first- or co-first-author outputs

- Strong specialty-specific networking and letters

- A clear narrative about your interests in that field.

You probably should not delay solely for research if:

- You’re going into IM, peds, FM, psych, EM, or other moderate/low-research specialties, and you’re already broadly competitive.

- The project is early, vague, or dependent on “if things go well.”

- The “big project” realistically yields only 1 paper and a couple of posters.

- You have no strong guarantee of a high-yield letter from a known person in the field.

And you almost certainly should not delay if:

- You hate research. You’re already burned out. You’re only doing this because others are panicking you into it. That tends to show, and programs pick up on it.

How to Make the Decision in Practice (What To Do This Week)

If you’re actually wrestling with this right now, here’s what I’d do in the next 1–2 weeks:

Schedule three conversations:

- One with your specialty advisor or PD

- One with your research PI (or potential PI)

- One with a recent grad who matched in your target specialty from your school

Take your projected CV and build two versions:

- Apply-now version

- Post-research-year version (be realistic, not fantasy)

Ask each person one direct question:

“Knowing what you know about this specialty and my goals, is this research year likely to move me from [tier X] to [tier Y], or from ‘at risk of not matching’ to ‘likely to match’?”Listen carefully to their first reaction. If they hesitate and say things like “Well, it could help,” that’s usually code for “Probably not worth losing a year.”

If two out of three trusted people don’t see a clear, strong benefit: do not delay.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Major boost in competitiveness | 25 |

| Moderate benefit | 35 |

| Little/no benefit | 30 |

| Net negative (burnout/weak output) | 10 |

Example Scenarios (So You Can See Yourself in One)

Scenario 1: Derm Applicant With Average Stats

- Step 2: 244

- Mid-tier MD school, no home derm program

- Research: 1 poster in heme/onc, 1 QI project

- Has offer for a 1-year derm research fellowship at a major academic center with a big-name PI

Here, a research year probably does make sense. You’re starting from a weak derm baseline and moving into a structured, high-yield environment that can generate multiple derm-focused outputs and a powerful letter. This can be the difference between “maybe 2–3 interviews” and “a realistic derm cycle.”

Scenario 2: IM Applicant With Decent Record

- Step 2: 242

- Solid clinical grades, no red flags

- A couple of posters and one middle-author paper in cardiology

- “Big project” is an outcomes study that might become a paper in 18 months

Should this person delay? Almost certainly not. For IM, they’re already in range for a wide spread of programs. One more paper isn’t going to dramatically move their match prospects. Losing a year for a marginal bump isn’t smart.

Scenario 3: Ortho Applicant With Low Step 2

- Step 2: 225

- Great rotations, strong letters from ortho faculty

- Research: almost nothing in ortho

- Offered a structured ortho research year with a productive group

Here, the key question is: “Can this research year plus networking plus strong letters offset the low Step 2 enough to make a match realistic?” In many ortho programs, yes—if the year is at a strong institution and you produce. In this setting, delaying might be your best shot at matching ortho instead of defaulting into a different specialty.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Want to delay for big research project |

| Step 2 | Probably do NOT delay |

| Step 3 | Delay year is REASONABLE to consider |

| Step 4 | Competitive, research-heavy specialty? |

| Step 5 | Current app clearly below target tier or at risk of not matching? |

| Step 6 | Structured, high-yield research year with strong mentor? |

| Step 7 | Realistically multiple strong outputs + big-name letter? |

Key Takeaways

- A research year is not automatically smart or dumb. It’s only worth it if it clearly changes your competitiveness in a research-heavy specialty with concrete, high-yield output and strong mentorship.

- Decide based on your specific specialty, actual project details, and honest baseline competitiveness, not vague fear or peer pressure.

- If trusted advisors can’t clearly articulate how the year upgrades your application tier, you probably should not give up a full year of your life to finish that “big project.”

FAQ: Delaying a Year for Research – 7 Common Questions

1. Will one more paper really change my chances of matching?

Usually, no. One additional publication, by itself, rarely flips your odds—especially in moderate-research fields like IM or peds. What matters is the pattern: multiple first-author works, a coherent research story in your chosen specialty, and visible productivity. A single “big” paper might impress academically, but program directors still mostly care about whether you look like a solid future resident with decent scores, strong letters, and good clinical performance.

2. Do program directors look down on research years or gap years?

Not automatically. In research-heavy specialties, a structured, productive research year is often seen as a plus—almost expected in some places. They do, however, look down on unstructured gap years with vague “research” and weak output. If you can clearly explain why you took the year and show real results, most PDs are fine with it. If your story is fuzzy and the CV doesn’t show much, that’s when eyebrows go up.

3. What if my project won’t be published before I apply, but we’ll submit it?

Submitted or “in preparation” is weaker than accepted, but it’s still something if:

- The work is clearly substantial and first-author

- You can describe methods and results well in interviews

- Your PI backs it up in a strong letter

Do not delay only so something can go from “submitted” to “accepted.” Delaying for that reason alone is usually not worth it.

4. Is it better to have many small projects or one big, impactful study?

For residency applications, many smaller but completed projects usually beat one giant, half-finished monster. Programs like to see a track record of follow-through and productivity. One huge RCT that might publish in 3–4 years helps your academic career long term, sure, but for residency, concrete, completed work they can actually see on your CV is more valuable.

5. How do I explain a research year in my personal statement and interviews?

You keep it simple and focused:

- “I took a dedicated research year in [field] to deepen my understanding of [specific topic] and contribute meaningfully to the specialty.”

- Briefly outline what you did (number/type of projects, key skills).

- Then tie it back to residency: how this prepared you to think critically, work on teams, and contribute to that program’s academic mission.

No drama. No long speeches about “finding yourself.” Clear, purposeful, and outcome-focused.

6. What if I’m still unsure about my specialty—should I take a research year to decide?

That’s usually a bad reason to delay. A research year locks you into a direction more than it helps you explore. If you’re unsure between, say, IM and EM, spending a year in a cardiology lab doesn’t resolve that. You’re better off getting more clinical exposure, mentorship, and honest advising than burning a year in a lab hoping clarity appears.

7. I already took one extra year (for research, LOA, or another degree). Is a second delay a problem?

Two added years start to raise questions. Not an automatic rejection, but programs will ask: Why so long? What were you doing? Did you progress? If you already have a research year or another gap, a second year must have an exceptionally strong justification and output. If your application is still borderline after one extra year, a second is more likely to look like stalling than progress.