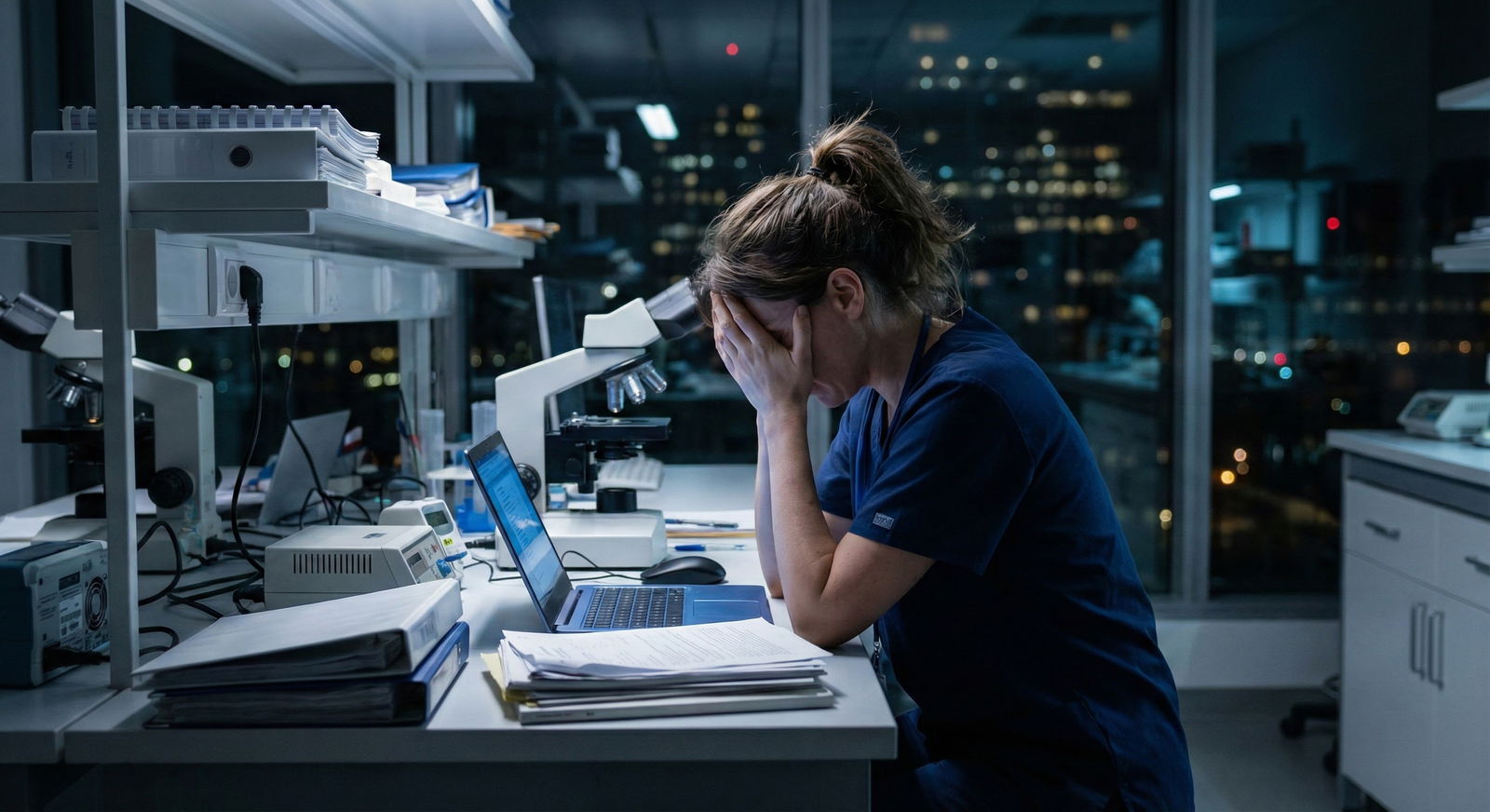

You’re sitting in a glass-walled conference room at the “top” lab on campus. The PI’s name is on half the posters at national meetings. Everyone keeps telling you, “This lab places people into MGH, UCSF, Mayo.”

You’ve been in this lab for 14 months.

Your CV?

One middle-author abstract that still says “submitted,” two projects that are “almost ready for submission,” and a “manuscript in preparation” that has been “in preparation” longer than some people’s relationships.

Match season is coming. Your inbox is full of interview invites asking you to “discuss your research in detail.” And you’re realizing: you bet on prestige… and lost time instead.

This is what I want to stop you from repeating.

Welcome to the shadow side of big labs.

The Big Lab Trap: Why Smart People Get Stuck

Let me be blunt: the biggest research mistake I see med students make for residency applications isn’t “not doing research.”

It’s doing research in the wrong environment.

Especially:

- Giant, famous labs where:

- The PI is never there

- There are 12 other trainees ahead of you on every project

- First authorship is a lottery

- Timelines move at geological speed

On paper, these places look unbeatable. Names you recognize. R01s everywhere. Massive Nature/NEJM/Cell papers on the wall.

In reality, for a lot of students applying to residency, they’re productivity graveyards.

Here’s the core lie people believe:

“If I join a big, prestigious lab, it’ll look good even if I don’t publish much.”

Residency PDs do not care how intimidating your PI is. They care what you produced.

- They care:

- First-author or significant middle-author papers

- Clear, coherent research story

- Impact aligned with your specialty

- They don’t care:

- That your PI knows three Nobel laureates

- That your lab uses a $1M microscope

- That the lab has a paper somewhere in NEJM if your name is nowhere near it

If you’re pre-residency, you’re not building a tenure dossier. You’re trying to get 1–3 solid, finished products on your CV and a story you can defend in an interview.

Big labs often destroy that simple goal.

Red Flags That Your “Prestige Lab” Is Actually Stalling You

These are patterns I’ve seen over and over. If you recognize 3–4 of these, you’re probably stuck.

1. Vague Project Ownership

You ask, “What will I work on?” and get:

- “We’ll figure it out once you’re settled.”

- “You’ll help with a few ongoing projects.”

- “We have tons of data; we just need someone to clean it.”

Translation:

You’re about to become the unpaid data janitor for projects where other people will get their names higher than yours.

Clear ownership sounds like:

- “You will lead Project X on Y topic.”

- “You’re first author if you do A, B, C.”

- “Here’s our target journal and rough timeline.”

No ownership = no guaranteed output = major risk.

2. Ten People on Every Project

You look at recent lab publications. Author lists are 10–25 names deep. Student authors are:

- 5th, 7th, 10th author

- Listed as “data collection,” “statistical support,” “image analysis”

That’s fine if you’re a full-time PhD student planning a long academic career.

For a med student or resident applicant? It’s a problem. Programs want to see that you:

- Drove a project

- Understood the methods

- Can explain decisions, not just say “I helped with the analysis”

Being buried at author position #9 on a mega-consortium paper is nice fluff. Not cornerstone material.

3. No Defined Timeline to Submission

You ask, “When do you think this will be ready to submit?” and everyone:

- Laughs

- Shrugs

- Says, “This is science; you can’t rush it”

Of course, you cannot force data to behave. But good mentors know how to scope projects to your timeline.

A safe answer looks like:

- “If you start now, we should have a draft in 4–6 months.”

- “We’ll aim to submit by the end of the academic year.”

- “These are the milestones you need to hit each month.”

If all you get is “We’ll see,” you’re signing up for multi-year drift.

4. PI Is a Ghost

You almost never see the PI. Lab meetings are run by:

- A senior postdoc who is overwhelmed

- A research coordinator juggling 10 studies

- A junior faculty who’s “acting PI” for half the projects

You meet with the actual PI:

- Once every 2–3 months

- For 15 minutes

- With five other people in the room

Good luck getting:

- Feedback on abstracts

- Timely edits on manuscripts

- Strong, specific letters of recommendation

Famous name, no actual mentorship = low yield.

5. You Hear the Same Phrases Over and Over

Listen for these classics:

- “Let’s collect more data before we write.”

- “We’re not ready to submit yet; the reviewers will tear it apart.”

- “We’ll aim higher first—maybe JAMA? If they reject, then we’ll move down.”

This is how 2–3 year delays happen in big-deal labs. They chase perfect instead of finished.

Residency programs do not reward “almost published in JAMA but we never actually submitted.” They reward “published in a solid specialty journal in time for ERAS.”

6. Past Trainee Output Is Weak for People Like You

Look at the CVs of previous med students (not PhDs, not postdocs):

- How many first-author papers did they have?

- How many were published before their residency application?

- Did they match where you want to match?

If students stay for 1–2 dedicated research years and walk away with:

- 0 first-author papers

- Only middle-author consortium papers

- “Manuscripts in preparation” that never actually appear online

That’s not an accident. That’s the lab’s real track record for people like you.

Why Big Labs Move So Slowly (And How It Hurts Your Match)

You need to understand why this happens, or you’ll fall for the same pattern again.

Structural Reasons Big Labs Stall Trainees

Too many layers of approval

- PI wants to review everything.

- Senior postdoc wants to review before PI.

- Statistician needs to “sign off.”

- Co-investigators want input.

Every figure, every paragraph, every submission gets stuck in a queue.

Perfectionism

- High-profile labs are terrified of mistakes.

- They’d rather:

- Delay 12 months for 10 more patients

- Run three more sensitivity analyses

- Add “just one more” experiment

Good science, terrible for your application timeline.

Power hierarchy

- Senior postdocs and fellows get first dibs on the best projects.

- Students collect data, clean databases, and prep figures.

- When a project is high-impact, the trainee closest to graduation or fellowship often gets the first-author slot.

If you’re the least senior person, you’re low priority.

Multiple competing priorities

- Your PI is:

- Writing grants

- Traveling to conferences

- Sitting on editorial boards

- Running multiple clinical trials

Your abstract? Your draft? Always “next week.”

- Your PI is:

How That Translates Into a Weak Application

Here’s how productivity delay shows up on ERAS:

| Category | Ideal by Application | Big Lab Reality (Common) |

|---|---|---|

| First-author papers | 1–3 | 0 |

| Middle-author papers | 2–5 | 1–2 (late, not online) |

| Abstracts/posters | 3–6 | 1–2 (local only) |

| Online PubMed entries | Several | 0–1 |

Programs don’t see your effort. They see your output. They see dates.

“2023–2025: Cardiovascular outcomes research, Big Name PI”

Output: “Manuscript in preparation”

A research year that doesn’t turn into citable products is a huge opportunity cost.

The CV Illusion: Prestige vs. Productivity

Let’s be clear. Both prestige and productivity matter. But for residency, productivity matters more.

Here’s where students get fooled.

They think:

- “Having Dr. Famous as my recommender will offset my lack of publications.”

- “PDs know how slow high-end labs move; they’ll understand.”

- “Being part of a major R01 group looks impressive by itself.”

This is naïve. Program directors are busy. They skim.

They’re scanning your ERAS and seeing:

- How many lines in “Peer Reviewed Journal Articles”

- How many posters

- Is there a coherent theme?

- Are you first-author anywhere?

They’re not doing a deep forensic analysis of why your big lab didn’t produce output in time. They just see the absence.

And letters?

- A generic, name-brand letter that says:

- “X was a pleasant and hardworking member of our team”

- “X contributed to several ongoing projects”

- Is weaker than a detailed, specific letter from a mid-tier PI who can say:

- “X led this project from idea to publication”

- “X drafted the manuscript and responded to peer review”

Big name + vague details is not better than small name + concrete achievements.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Big-name, low-output lab | 40 |

| Moderate-name, strong output | 80 |

| No-name, exceptional output | 90 |

(Think of those values as “how much this helps your residency application,” not lab reputation.)

Safe Lab Choices: What Actually Helps Your Application

So how do you avoid the prestige trap and pick something that moves?

Look for These Green Flags

Clear, scoped projects for students

- The PI or mentor can describe:

- A specific, bite-sized project

- Realistic data needs

- Target journal or conference

- Month-by-month plan

- The PI or mentor can describe:

Documented student output

- Previous med students:

- Have first-author papers

- Published before applying

- Got into solid programs

- The PI can say, “Our students usually get X, Y, Z out of a year.”

- Previous med students:

Accessible mentor

- You see the PI regularly.

- They read and edit drafts within 1–2 weeks.

- They show up to lab meeting and know your name and project.

Willingness to publish “good enough” work

- They do not insist on JAMA for every project.

- They understand that:

- Specialty journals are fine

- A solid retrospective or QI project is valuable

- Deadlines like ERAS matter

You are first on at least one thing

- From day one, it’s clear:

- “This one is yours.”

- You are not just “helping out” indefinitely.

- From day one, it’s clear:

If You’re Already Stuck in a Big Lab: How to Cut Your Losses

This is the uncomfortable part. But necessary.

If you’re already 6–18 months into a prestige lab and your CV is thin, you have two priorities:

- Salvage what you can.

- Stop the bleeding.

Step 1: Reality Check Conversation

Schedule a direct meeting with your PI or main mentor. Go in with:

- Your current CV

- A timeline to residency application (dates in hand)

- List of projects you’ve touched

Then ask, without fluff:

- “What is realistically going to be submitted and accepted before ERAS opens?”

- “Which projects can I be first author on?”

- “What is the earliest target deadline for submission on each?”

Watch for their reaction.

If they:

- Give specific answers

- Commit to deadlines

- Acknowledge the time pressure

There’s hope.

If they:

- Hand-wave

- Talk only about long-term vision

- Say, “No one can promise timelines in research”

You have your answer.

Step 2: Downscope and Prioritize

Push to carve out:

- A smaller, self-contained analysis

- A brief report

- A methods paper

- A sub-study that can actually be finished

Propose:

- “Could I write up X dataset as a short communication?”

- “Is there a retrospective angle we can publish faster?”

- “Can I take the lead on a smaller project with a clear deadline?”

You might get more traction with something modest but doable.

Step 3: Add a Second, Faster Environment

Do not rely on a single slow-moving, prestige behemoth if time is short. Consider:

- A small QI project with a clinician in your target specialty

- A case series or case report pipeline

- A chart review with a junior faculty who’s hungry to publish

These smaller units often move faster because:

- Less bureaucracy

- Fewer stakeholders

- Lower “prestige anxiety”

I’ve seen students get more from a 6-month QI project than from 2 years in a monster lab.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Realize CV is thin |

| Step 2 | Meet with PI for reality check |

| Step 3 | Downscope project & set milestones |

| Step 4 | Shift focus to faster projects |

| Step 5 | Add small QI or chart review |

| Step 6 | Submit at least one paper/abstract before ERAS |

| Step 7 | Concrete plan with deadlines? |

Step 4: Be Willing to Walk

The sunk cost fallacy will kill you here.

You’ll think:

- “I’ve already put in a year, I can’t leave now.”

- “If I bail, I’ll burn bridges.”

- “What if something finally gets published right after I leave?”

Here’s the brutal truth:

- A year of “almost something” doesn’t beat 6–9 months of “definitely published”

- You can stay nominally attached to the big lab as a collaborator while focusing your active time elsewhere

- Bridges that require you to sacrifice your future are not worth keeping intact

You’re not quitting science. You’re protecting your match.

How to Vet a Lab Before You Commit

If you’re early in the process, good. You can avoid this mess entirely.

Use these questions when you’re meeting potential mentors:

“What have previous medical students produced from working with you?”

- Look for hard numbers:

- “Most students get 1–2 first-author papers and a few posters.”

- Ask to see examples of their past trainees’ CVs (people do this more than you think).

- Look for hard numbers:

“What project would you see me leading, and what’s the realistic timeline?”

- If they cannot answer concretely, that’s a red flag.

“How often do you meet one-on-one with your students?”

- Monthly or more is reasonable.

- “As needed” = usually never.

“Do you have experience helping students who are applying in [YOUR SPECIALTY]?”

- If you’re going into derm, rads, ortho, etc., you need someone who understands:

- Application timelines

- Expectations

- How to pitch your work

- If you’re going into derm, rads, ortho, etc., you need someone who understands:

“If a project turns out not to be high impact, would you still support publishing it in a smaller journal?”

- You want a yes here.

- “We only shoot for top-tier” is cool for postdocs, bad for you.

Common Rationalizations That Will Hurt You

Let me kill a few comforting lies up front:

- “It’s okay if nothing publishes; I’ll just talk about it in interviews.”

- Weak. Interviewers will ask, “So did that ever get submitted?”

- “I have strong Step scores; research is just a bonus.”

- In competitive specialties, research is not a bonus. It’s expected.

- “PDs will know how rigorous this lab is, even without papers.”

- They don’t have time for that forensic analysis.

- “Manuscripts in preparation look fine on ERAS.”

- Everyone has “manuscripts in preparation.” PDs trust PubMed, not promises.

Stop selling yourself on stories that only make sense if you ignore how program directors actually review applications.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. Is it ever worth staying in a big, slow lab?

Yes, but only under specific conditions. If you already have at least one strong first-author paper submitted or accepted, and your PI is actively pushing a second project toward submission before ERAS, staying might be reasonable. Also, if you’re absolutely set on a long-term academic career and can afford a slower start, the big-name network can pay off later. But if you’re behind on output and timelines are vague, loyalty to the lab should not outrank loyalty to your own future.

2. How many publications do I actually need for a competitive residency?

It depends on the specialty and your school, but for research-heavy fields (derm, rads, ortho, neurosurg), I’d aim for:

- At least 1–2 first-author papers or substantial abstracts

- Several middle-author works

- A coherent narrative in one or two themes

For less research-intensive fields, even one well-executed, first-author project plus a few posters can be enough—if the story is clear and your mentor backs you with a strong letter. The problem isn’t having “only” a few; it’s having nothing finished.

3. Should I ever list “manuscript in preparation” on ERAS?

You can, but do not rely on it. Programs know this category is bloated with vaporware. If you list it, be prepared to:

- Explain clearly what stage it’s in

- Describe your specific role

- Give a realistic expectation of submission

If it’s not at least drafted and under active revision with your co-authors, I’d think twice before putting it front and center. It will not rescue an otherwise empty publications section.

4. How late is “too late” to switch labs or projects before applying?

I’ve seen people salvage their applications 6–9 months before ERAS by pivoting to:

- Focused QI projects

- Data sets that were already collected but not analyzed

- Short communications or case series

The later you switch, the smaller the projects need to be. If you’re <6 months from application, don’t start anything massive. Instead, target things that can realistically: - Be submitted as an abstract

- Produce a poster

- Potentially get accepted as a brief report

The worst move is staying locked in a dead-end project out of guilt when you know, in your gut, it won’t be done in time.

Open your CV right now and count how many submitted or published first-author items you have. If that number is zero and you’re betting on a big lab to “come through soon,” write down three names of smaller, faster-moving mentors you could talk to this month—and email the first one today.